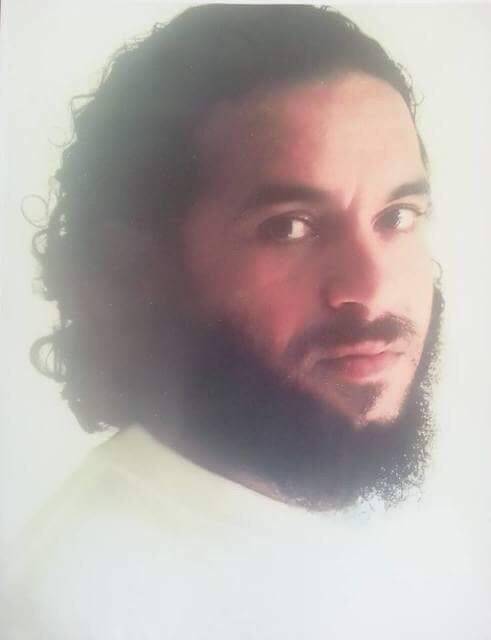

This is the story of an Afghan citizen Asadullah Haroon Gul who is being held without charge or trial in Guantanamo Bay detention camp for the last 13 years.

I am entering my thirteenth year in Guantánamo Bay. I am fast approaching my fortieth year. Will I still be here when I reach fifty? What do I say to my mother on the rare occasions I get to speak to her on Skype? What do I say to my wife? My detention here is directly responsible for the death of my respected father-in-law. Years ago, in the Russian war, his son was captured and killed by the communists; he had a heart attack and died when he learned I was in Guantánamo.

My dearly beloved daughter was three months old when I was seized by the Americans, interrogated in Bagram, and hauled twelve thousand kilometers around the world to Guantánamo. She is now a teenager. I get to talk to her on a rare occasion, but I don’t really know her. I’ve missed her whole life.

The Americans have a saying, that God helps those who help themselves. I do not know what I am meant to do to get out of here. In 2009, the soldiers from the military commissions said I should “do a deal” to go home. I said I would do almost anything. In 2010, the FBI said the same. Likewise, they never told me what I had to do. The authorities promised me that the Periodic Review Board (PRB) would give me the chance to show that I should be sent home. When I finally got a PRB in 2016, the military officer said I had a fifty-fifty chance of winning at the start, but at the end she said it was one hundred percent sure. I lost. They want me to confess to something that is not true. They want me to say that I was part of Al Qaeda when I was not. I am not going to lie, not even if it means saving myself. I want release through a clean and just process, not through complicity in an unlawful sham.

In 2017, President Donald Trump made it government policy that nobody would leave Guantánamo on his watch. I dared to hope anyway, since Ahmed al Darbi went back to Saudi Arabia last year. I had another hearing with the PRB. Although my military representative said I had done very well, I lost once more.

For nine years, I had no legal help. I was held in isolation. I have kept track — I asked for lawyer more than 300 times, in letters to the outside to everyone I could think of. For almost a decade, I never received a reply. The military said they would bring me a lawyer. They did not.

In the end, tracing the example of Gandhi, I went on a peaceful hunger strike just to get a lawyer. I dropped from 145 to just 92 pounds in weight. I had to do it twice. Finally in 2016, I managed to get the attention of the charity Reprieve, as well as my brilliant lawyer Tara Plochocki at Lewis Baach in Washington. At last I had hope, but hope is a dangerous thing when you are powerless.

We all hope the war in Afghanistan is over. I want a better, calmer country for my daughter. But we can hardly expect peace if the U.S. is allowed to say that I am still a prisoner of war.

Originally they said I was a member of HIG. That much was true, and I have always said I was; I am glad that HIG is now a part of the peace process. If this is so, I can hardly be a prisoner of war. So the U.S. now wants to forget all this about HIG, and say I was a member of Al Qaida. This is nonsense — I have always wanted Al Qaeda out of our country, so we can deliver peace for my daughter, and for the children of everyone else.

I know I am unlikely ever to play a major role for my country, but I have given it a lot of thought from afar, from here in Guantánamo. I would want a strong central government, a strong presidency, independent judges to protect the people, and a military that is totally separate from the government, with the sole job of defending the country from outside threats. Most of all, I would want peace and stability.

My daughter has big ambitions and I support her. Contrary to the ridiculous stereotypes harboured by some in the West—that we are backward people who want to lock our women in the kitchen—I want everything best for her in our modern world. She tells me she wants to be a teacher; I would like her to be a doctor, but she can go where her passions lead her.

My greatest ambition in life is to help to leave her a country that is safe, where she can live a good life, and achieve all her own ambitions. I was born in a refugee camp across the border in Pakistan, and I never had a life of peace. I want something much better for her.

I won’t ever be president, but I have goals for when I come home. I have created a plan for the Marmam honey farm project. I have another plan for a traditional bakery. I have tried to gain the education I never had, and have two certificates of achievement for computer skills. My first job is to look after my family; next, to help rebuild my beautiful country.

But first someone needs to convince the US to follow the law and release me. I have the help of US lawyers working for charity, but I want the help of the Afghan government too. Will I receive it, or must I rely on the charity of Americans to do what my own government should be doing?

Guantánamo Bay is torture. It always was, and it always will be. It defines the word, but now in a very unique way for me. While the black hole without law was created to hold “prisoners of war” from Afghanistan, I am the only, solitary Afghan citizen who will never face any kind of trial. A minority of one. They spend $11.8 million dollars to keep me here each year, and the same for each other prisoner. They think a few people (just 16) are “High Value Detainees” who they want to prosecute for an alleged crime; the other 24 of us are “no value detainees.” I have even less than no value.

I was part of an Afghan nationalist group that entered into a peace treaty with Afghanistan over two years ago.

I remain here with the others as a pawn in a political game, as President Donald Trump says nobody will leave here under his watch. If he is re-elected, that has a very special meaning for me: at least another four years when I have no chance of returning home.

Sometimes I lose my final thread of hope. I have been here for twelve very long years. People talk about torture. It is true that they beat me, and subjected me to strappado (an old medieval abuse where they hang you by your slowly dislocating shoulders). That was terrible, yet the mere experience of remaining here, perhaps forever, is as bad as it gets.

The Behavioral Health Unit (BHU) says I need medication for the insomnia I suffer here in Guantánamo Bay. They say it is all a result of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) that comes as a result of my torture – the fear, the suddenly elevated heart-beat, the anger, even the longing no longer to be alive. But I hate to take their medication. I have nightmares every time I close my eyes.

Most of the time, I am walking through snakes, there are dogs chasing me, and people thrashing me. Then they throw me from a high house, or a hurricane sweeps through here and I am jerked to wakefulness just as it kills me.

Guantánamo is not easy. What kind of help do you get here? The people who say they would help me are the same who tortured me. The BHU has long been part of the interrogation process, where the medical personnel would advise the interrogators how best to exploit our deepest phobias.

Even today, there is a camera watching me every moment of my life. The moment my cell door is locked, the claustrophobia closes in once more. My chest tightens. I find myself yelling out loud for my freedom.

Every now and then I get to have a Skype call with my family. I treasure them, but they can add to my sadness, as I do to theirs. My dear mother should still be full of vitality, but she looks much older than she is, hunched over like an old woman. She has raised five of us children and I am the youngest. “Your detention broke my back,” she told me. I spoke to my wife, too briefly. “When you are in prison, I am as well,” she told me. I was in my early twenties when I was rounded up and rendered half way around the world to this hellish place. Now, I am coming up on forty. The best of my life is slipping away here.

Sometimes I think of Kabul Zoo. I went there when I was sixteen. The animals had more space to move, even in the height of the Afghan war. I remember an elephant feeding – he seemed to wink at me. I have a few hours of recreation out in the yard twice a week – he would be out all day every day. Nobody ever shackled him. Families would come to see him – my family can never visit me in Guantánamo Bay.

Indeed, even here the animals have more rights than us. If a soldier hits an iguana, he gets a $10,000 fine and ten years in prison; they used to hit the detainees as part of their duty. There are feral cats near the yard here. The cats have their liberty, though from time to time the military wages war on them too. I used to get punished for feeding them. I have a favorite, who I call Ameera (Princess). I mix her up a dinner from the remains of the food given to me in Styrofoam containers.

Has the Afghan government forgotten me? Do they even know I am still here? Mahatma Gandhi said, “If you want action, do it yourself.” I wish I could do that but I am trapped in a small cell forever, charged with no crime, offered no trial.

I do desperately hope that my country offers peace to the next generation, yet I ask myself – how can the American expect there to be peace in Afghanistan without justice? There will be no justice as long as they continue to hold me, a lonely Afghan held prisoner of a war that is not even being fought anymore, 12,881 kilometers from Kabul.

I am entering my thirteenth year in Guantánamo Bay. I am fast approaching my fortieth year. Will I still be here when I reach fifty? What do I say to my mother on the rare occasions I get to speak to her on Skype? What do I say to my wife? My detention here is directly responsible for the death of my respected father-in-law. Years ago, in the Russian war, his son was captured and killed by the communists; he had a heart attack and died when he learned I was in Guantánamo.

My dearly beloved daughter was three months old when I was seized by the Americans, interrogated in Bagram, and hauled twelve thousand kilometers around the world to Guantánamo. She is now a teenager. I get to talk to her on a rare occasion, but I don’t really know her. I’ve missed her whole life.

The Americans have a saying, that God helps those who help themselves. I do not know what I am meant to do to get out of here. In 2009, the soldiers from the military commissions said I should “do a deal” to go home. I said I would do almost anything. In 2010, the FBI said the same. Likewise, they never told me what I had to do. The authorities promised me that the Periodic Review Board (PRB) would give me the chance to show that I should be sent home. When I finally got a PRB in 2016, the military officer said I had a fifty-fifty chance of winning at the start, but at the end she said it was one hundred percent sure. I lost. They want me to confess to something that is not true. They want me to say that I was part of Al Qaeda when I was not. I am not going to lie, not even if it means saving myself. I want release through a clean and just process, not through complicity in an unlawful sham.

In 2017, President Donald Trump made it government policy that nobody would leave Guantánamo on his watch. I dared to hope anyway, since Ahmed al Darbi went back to Saudi Arabia last year. I had another hearing with the PRB. Although my military representative said I had done very well, I lost once more.

For nine years, I had no legal help. I was held in isolation. I have kept track — I asked for lawyer more than 300 times, in letters to the outside to everyone I could think of. For almost a decade, I never received a reply. The military said they would bring me a lawyer. They did not.

In the end, tracing the example of Gandhi, I went on a peaceful hunger strike just to get a lawyer. I dropped from 145 to just 92 pounds in weight. I had to do it twice. Finally in 2016, I managed to get the attention of the charity Reprieve, as well as my brilliant lawyer Tara Plochocki at Lewis Baach in Washington. At last I had hope, but hope is a dangerous thing when you are powerless.

We all hope the war in Afghanistan is over. I want a better, calmer country for my daughter. But we can hardly expect peace if the U.S. is allowed to say that I am still a prisoner of war.

Originally they said I was a member of HIG. That much was true, and I have always said I was; I am glad that HIG is now a part of the peace process. If this is so, I can hardly be a prisoner of war. So the U.S. now wants to forget all this about HIG, and say I was a member of Al Qaida. This is nonsense — I have always wanted Al Qaeda out of our country, so we can deliver peace for my daughter, and for the children of everyone else.

I know I am unlikely ever to play a major role for my country, but I have given it a lot of thought from afar, from here in Guantánamo. I would want a strong central government, a strong presidency, independent judges to protect the people, and a military that is totally separate from the government, with the sole job of defending the country from outside threats. Most of all, I would want peace and stability.

My daughter has big ambitions and I support her. Contrary to the ridiculous stereotypes harboured by some in the West—that we are backward people who want to lock our women in the kitchen—I want everything best for her in our modern world. She tells me she wants to be a teacher; I would like her to be a doctor, but she can go where her passions lead her.

My greatest ambition in life is to help to leave her a country that is safe, where she can live a good life, and achieve all her own ambitions. I was born in a refugee camp across the border in Pakistan, and I never had a life of peace. I want something much better for her.

I won’t ever be president, but I have goals for when I come home. I have created a plan for the Marmam honey farm project. I have another plan for a traditional bakery. I have tried to gain the education I never had, and have two certificates of achievement for computer skills. My first job is to look after my family; next, to help rebuild my beautiful country.

But first someone needs to convince the US to follow the law and release me. I have the help of US lawyers working for charity, but I want the help of the Afghan government too. Will I receive it, or must I rely on the charity of Americans to do what my own government should be doing?

Guantánamo Bay is torture. It always was, and it always will be. It defines the word, but now in a very unique way for me. While the black hole without law was created to hold “prisoners of war” from Afghanistan, I am the only, solitary Afghan citizen who will never face any kind of trial. A minority of one. They spend $11.8 million dollars to keep me here each year, and the same for each other prisoner. They think a few people (just 16) are “High Value Detainees” who they want to prosecute for an alleged crime; the other 24 of us are “no value detainees.” I have even less than no value.

I was part of an Afghan nationalist group that entered into a peace treaty with Afghanistan over two years ago.

I remain here with the others as a pawn in a political game, as President Donald Trump says nobody will leave here under his watch. If he is re-elected, that has a very special meaning for me: at least another four years when I have no chance of returning home.

Sometimes I lose my final thread of hope. I have been here for twelve very long years. People talk about torture. It is true that they beat me, and subjected me to strappado (an old medieval abuse where they hang you by your slowly dislocating shoulders). That was terrible, yet the mere experience of remaining here, perhaps forever, is as bad as it gets.

The Behavioral Health Unit (BHU) says I need medication for the insomnia I suffer here in Guantánamo Bay. They say it is all a result of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) that comes as a result of my torture – the fear, the suddenly elevated heart-beat, the anger, even the longing no longer to be alive. But I hate to take their medication. I have nightmares every time I close my eyes.

Most of the time, I am walking through snakes, there are dogs chasing me, and people thrashing me. Then they throw me from a high house, or a hurricane sweeps through here and I am jerked to wakefulness just as it kills me.

Guantánamo is not easy. What kind of help do you get here? The people who say they would help me are the same who tortured me. The BHU has long been part of the interrogation process, where the medical personnel would advise the interrogators how best to exploit our deepest phobias.

Even today, there is a camera watching me every moment of my life. The moment my cell door is locked, the claustrophobia closes in once more. My chest tightens. I find myself yelling out loud for my freedom.

Every now and then I get to have a Skype call with my family. I treasure them, but they can add to my sadness, as I do to theirs. My dear mother should still be full of vitality, but she looks much older than she is, hunched over like an old woman. She has raised five of us children and I am the youngest. “Your detention broke my back,” she told me. I spoke to my wife, too briefly. “When you are in prison, I am as well,” she told me. I was in my early twenties when I was rounded up and rendered half way around the world to this hellish place. Now, I am coming up on forty. The best of my life is slipping away here.

Sometimes I think of Kabul Zoo. I went there when I was sixteen. The animals had more space to move, even in the height of the Afghan war. I remember an elephant feeding – he seemed to wink at me. I have a few hours of recreation out in the yard twice a week – he would be out all day every day. Nobody ever shackled him. Families would come to see him – my family can never visit me in Guantánamo Bay.

Indeed, even here the animals have more rights than us. If a soldier hits an iguana, he gets a $10,000 fine and ten years in prison; they used to hit the detainees as part of their duty. There are feral cats near the yard here. The cats have their liberty, though from time to time the military wages war on them too. I used to get punished for feeding them. I have a favorite, who I call Ameera (Princess). I mix her up a dinner from the remains of the food given to me in Styrofoam containers.

Has the Afghan government forgotten me? Do they even know I am still here? Mahatma Gandhi said, “If you want action, do it yourself.” I wish I could do that but I am trapped in a small cell forever, charged with no crime, offered no trial.

I do desperately hope that my country offers peace to the next generation, yet I ask myself – how can the American expect there to be peace in Afghanistan without justice? There will be no justice as long as they continue to hold me, a lonely Afghan held prisoner of a war that is not even being fought anymore, 12,881 kilometers from Kabul.