We are again and again forced to confront the fact that Pakistan is among the countries with the most deplorable record when it comes to freedom of religion. It has been listed among the “Countries of Particular Concern” in annual report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF). Religious freedom has always been a matter of critical concern since the country’s inception. The founder of country Muhammad Ali Jinnah left no stone unturned in emphasizing his belief in citizenship and equality of all citizens. But the legacy he left was undermined by the movement against the Ahmadiya community in the 1950s, which, later in the mid-1970s, paved the way for the Second Amendment in the Constitution of Pakistan 1973. This was almost the start of the formal Islamization of laws.

Once the state affirms equal citizenship, it must treat the citizens impartially, endorsed in the article 25 of the Constitution. But the process started in 1973 continued, heedless of such considerations. The martial law regime came in full swing in the 1980s by putting more restrictions under section 298-B and 298-C of the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC), curtailing more religious rights of the Ahmadiyya community. It would not amaze the readers to know that an Ahmadi can be imprisoned up to three years for representing themselves as a Muslim or for preaching their religion.

Yet another development in this process was exclusion of the Ahmadiyya community from National Minorities Commission earlier this year, even denying their existent as minority. Some experts are of the view that: it is not even a violation of article 18 of ICCPR but it falls quite simply under persecution of a particular community.

Among the principles of democracy, one of the most important is equal citizenship. Yet we see article 41 (2) which doesn’t allow any religious community except Muslims to contest for presidency. Similarly, article 91 (3) excludes all the communities from the possibility of being prime minister, except Muslims. Both these articles stand against article 27, which calls for no discrimination on the bases of religion. When a self-proclaimed Islamic State doesn’t treat its subjects equally, it finds little justification for questioning the persecution of Muslims in India, Myanmar, Palestine or France. No moral justification can be brought when a state itself discriminates on the basis of religion.

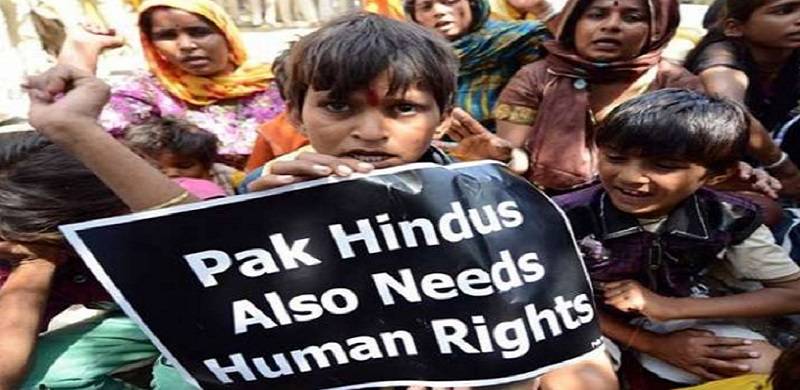

The freedom to adopt or change religion is a widely accepted human and natural right. Pakistan witnesses, on average, one thousand cases of “forced religious conversion” annually, mostly in the southern part of the country. It seems that mostly religious clerics, apparently using seminaries, are given this task. Most of these cases subsequently go in favour of a victim’s family in the court of law. In a recent case, Mehek Kumari, a 16-year-old Hindu was abducted from home and later, converted. She confessed in the court that she no more wants to live with her husband, who had acted despite knowing that she was underage. Although underage marriage is a punishable crime under section 3 of the “Child Marriage Restraint Act 2014”, culprits go untouched because of support from local religious clerics and seminaries. Even the religion that they claim to represent doesn’t allow them to do so under the verse of Quran: “There is no compulsion in religion”.

A properly organized and peaceful religion must be open to criticism and critical debate, but this country has witnessed otherwise. To question things is considered blasphemy, or it leads to society’s outrage. This is not necessarily because our society is originally so intolerant or bigoted, but on account of the curriculum and lines of thinking that we have set.

Some of the legislation mentioned above is simply incompatible with human freedom and dignity – even by Pakistani standards. After all, it was not always in existence, but was gradually introduced.

The sense of intolerance and bigotry in society reached a new height with the assassination of Salman Taseer, then serving governor of the largest province of the country. He was murdered in 2011 after his remarks which were seen as being critical of the blasphemy law. Since 1992, 62 persons have been extra-judicially murdered. It might surprise readers that not a single accused has been convicted in a court of law. In fact, the law appears to have been consistently misused for the benefit of influential people, who try to win their personal disputes by means of dubious allegations. Not to mention the whole case of Asia Bibi, who spent 9 years imprisoned just to get acquittal from the Supreme Court. Recently, a university professor was arrested in Sindh on alleged blasphemy charges because of his personal quarrel with a religious cleric.

Reports of fake blasphemy charges have not ended, nor are they likely to. Only amendment and reformation of laws can put an end to losing precious lives.

Islamization of laws has had a great effect on religious freedom, making the people more prone to outrage and more sensitive. Aside from the reform and amendment process mentioned above, there is an urgent need for updating the curriculum so that we can create a more tolerant and inclusive society.

Once the state affirms equal citizenship, it must treat the citizens impartially, endorsed in the article 25 of the Constitution. But the process started in 1973 continued, heedless of such considerations. The martial law regime came in full swing in the 1980s by putting more restrictions under section 298-B and 298-C of the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC), curtailing more religious rights of the Ahmadiyya community. It would not amaze the readers to know that an Ahmadi can be imprisoned up to three years for representing themselves as a Muslim or for preaching their religion.

Yet another development in this process was exclusion of the Ahmadiyya community from National Minorities Commission earlier this year, even denying their existent as minority. Some experts are of the view that: it is not even a violation of article 18 of ICCPR but it falls quite simply under persecution of a particular community.

Among the principles of democracy, one of the most important is equal citizenship. Yet we see article 41 (2) which doesn’t allow any religious community except Muslims to contest for presidency. Similarly, article 91 (3) excludes all the communities from the possibility of being prime minister, except Muslims. Both these articles stand against article 27, which calls for no discrimination on the bases of religion. When a self-proclaimed Islamic State doesn’t treat its subjects equally, it finds little justification for questioning the persecution of Muslims in India, Myanmar, Palestine or France. No moral justification can be brought when a state itself discriminates on the basis of religion.

The freedom to adopt or change religion is a widely accepted human and natural right. Pakistan witnesses, on average, one thousand cases of “forced religious conversion” annually, mostly in the southern part of the country. It seems that mostly religious clerics, apparently using seminaries, are given this task. Most of these cases subsequently go in favour of a victim’s family in the court of law. In a recent case, Mehek Kumari, a 16-year-old Hindu was abducted from home and later, converted. She confessed in the court that she no more wants to live with her husband, who had acted despite knowing that she was underage. Although underage marriage is a punishable crime under section 3 of the “Child Marriage Restraint Act 2014”, culprits go untouched because of support from local religious clerics and seminaries. Even the religion that they claim to represent doesn’t allow them to do so under the verse of Quran: “There is no compulsion in religion”.

A properly organized and peaceful religion must be open to criticism and critical debate, but this country has witnessed otherwise. To question things is considered blasphemy, or it leads to society’s outrage. This is not necessarily because our society is originally so intolerant or bigoted, but on account of the curriculum and lines of thinking that we have set.

Some of the legislation mentioned above is simply incompatible with human freedom and dignity – even by Pakistani standards. After all, it was not always in existence, but was gradually introduced.

The sense of intolerance and bigotry in society reached a new height with the assassination of Salman Taseer, then serving governor of the largest province of the country. He was murdered in 2011 after his remarks which were seen as being critical of the blasphemy law. Since 1992, 62 persons have been extra-judicially murdered. It might surprise readers that not a single accused has been convicted in a court of law. In fact, the law appears to have been consistently misused for the benefit of influential people, who try to win their personal disputes by means of dubious allegations. Not to mention the whole case of Asia Bibi, who spent 9 years imprisoned just to get acquittal from the Supreme Court. Recently, a university professor was arrested in Sindh on alleged blasphemy charges because of his personal quarrel with a religious cleric.

Reports of fake blasphemy charges have not ended, nor are they likely to. Only amendment and reformation of laws can put an end to losing precious lives.

Islamization of laws has had a great effect on religious freedom, making the people more prone to outrage and more sensitive. Aside from the reform and amendment process mentioned above, there is an urgent need for updating the curriculum so that we can create a more tolerant and inclusive society.