By Ali Warsi, Omer Bhatti and Ziyad Faisal

On April 13, Lahore High Court’s (LHC) two-member bench comprising Justice Sardar Muhammad Sarfraz Dogar and Justice Asjad Javed Ghural granted Pakistan Muslim League – Nawaz (PMLN) president Shehbaz Sharif bail in the money-laundering case. While reading the short order, the court reader announced that Sharif’s bail application had been accepted against two bail bonds worth Rs 5 million each, and that the detailed judgment was to be issued later.

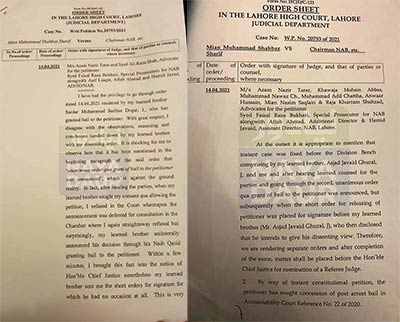

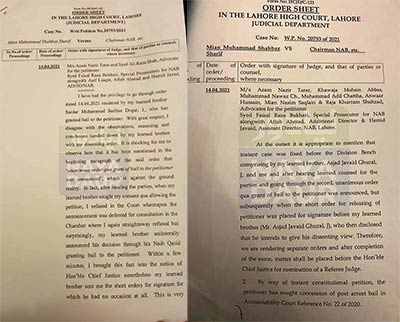

However, it turned out later that Justice Ghural had refused to sign the short order written by his colleague Justice Dogar. The next day, Justice Ghural came to the High Court, heard cases but did not go to the division bench resulting in cancellation of the cause list of the day. On April 16, reports started circulating that PMLN leaders kept sitting outside Justice Ghural’s chamber throughout the day but the learned judge left for home without signing the judgment. On Sunday, finally, Justice Ghural wrote his decision denying bail to the former Punjab Chief Minister and also narrated the whole incident that had transpired on April 13. In his decision, he wrote how he disagreed with the ‘observations, reasoning and the conclusion handed down by the learned brother’ Justice Sarfraz Dogar. He went on to add: “It is shocking for me to observe here that it has been mentioned in the beginning paragraph of the said order that ‘unanimous order qua grant of bail to the petitioner was announced’, which is against the ground reality. In fact, after hearing the parties, when my learned brother sought my consent qua allowing the petition, I refused … but surprisingly, my learned brother unilaterally announced his decision through his Naib Qasid granting bail to the petitioner.”

In his judgment, Justice Sarfraz Dogar laid out his version of the day’s events. “… after hearing learned counsel for the parties and going through the record, unanimous order qua grant of bail to the petitioner was announced, but subsequently when the short order for releasing of petitioner was place for signature before my learned brother (Mr. Asjad Javed Ghural, J), who then disclosed that he intends to give his dissenting view. Therefore, we are rendering separate orders and after completion of the same, matter shall be placed before the Hon’ble Chief Justice for nomination of a Referee Judge.”

This was an unprecedented situation. Later, the LHC Chief Justice Muhammad Qasim Khan formed a new three-member bench to examine the matter and Sharif was granted bail on April 23.

But the earlier fisaco has baffled legal experts as to how a disagreement between the judges blew up in full public view with one of the judges announcing a unanimous order while the other was writing a dissenting note.

‘This decision can damage the integrity of the court’

Former Attorney General Irfan Qadir says that this was an abnormal situation. Talking to anchor Kamran Khan on Dunya TV, Qadir said that it was unprecedented for a verdict to be changed, especially in higher courts, after being announced by the reader. “I can’t even remember a situation where judges disagreed on a bail matter. Generally, even if one of the judges considers the case doubtful and thinks the accused should be granted the bail, the other judge doesn’t resist that. In bail cases at least, this is not normal. I’m surprised myself and believe this decision can damage the integrity of the court. Let’s not forget the Supreme Court has already expressed its concerns regarding political engineering in such high profile political cases”, Qadir said.

He listed three things for a judge to consider in a bail case. “First, the judge should look at the merits of the case. Second, the judges review the medical condition of the petitioner. And third, in political cases, they must also see if the petitioner was being persecuted for the sake of political engineering. If we look at all these things, and the fact that order was announced in the court, how could they leave the matter without a conclusion? Once an announcement is made in the court, the order following it is not supposed to contradict it. Such a situation is looked at with suspicion. This is unusual. This should never happen,” he said.

‘This appeared dubious and out of the ordinary’

Pakistan’s Judiciary has always come under criticism for perceived partisanship and decisions influenced by exogenous factors. The Shehbaz Sharif Bail case is one such example, where a dissenting note was given 4 full days after release on bail order. Speaking to Naya Daur Media, Muhammad Zubair Umer, Nawaz Sharif’s spokesperson, argued that if one judge is overwhelmingly inclined to release the accused on bail, then it is commonly accepted practice for the other to follow suit. Naya Daur Media asked Zubair Umer about the possible reasons according to him behind an extremely late dissenting note. The former governor of Sindh province commented that while judicial history and past is littered with examples of decisions based on extra legal reasoning under various external influences, he was not fully aware as to why the dissenting note in this case had come after 4 days had elapsed. He admitted that this appeared dubious and out of the ordinary. However, he expressed confidence in the court for the matter to be adjudicated reasonably.

Divisions in the Supreme Court?

But such divisions within the bench are not just limited to the Lahore High Court. An even more intriguing situation is developing in Supreme Court where the fourth most senior judge of the apex court is currently pleading his case before a 10-member bench.

A presidential reference was filed against Justice Qazi Faez Isa — in line to become the chief justice on September 18, 2023, for 13 months — in May 2019. Although the 10-member bench had unanimously quashed the reference in its June 19, 2020 decision, 7 out of the 10 judges agreed that the assets of Justice Qazi Faez Isa’s wife Mrs Sarina Isa should be further investigated. Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) was directed to initiate an investigation into the assets and submit the report before Supreme Judicial Council within 75 days. Senior lawyer Babar Sattar had termed the decision ‘a complaint-in-waiting against Qazi Faez Isa to be taken up in 75 days’. Justice Isa for reasons obvious filed a review petition.

The petition is currently being heard by a 10-member bench headed by Justice Umar Ata Bandial, the senior most judge in Supreme Court after Chief Justice Gulzar Ahmed. An application seeking permission for live streaming the hearings of the review petition hearings was rejected by the bench in a 6-4 verdict. The judges who were in favour of live streaming included Justice Manzoor Malik, Justice Mazhar Alam Miankhel, Justice Mansoor Ali Shah and Justice Yahya Afridi. Justices Shah and Afridi have already given their verdict in Justice Qazi Faez Isa’s favour in the original decision. Now that Justice Manzoor Malik and Mazhar Alam Miankhel have also joined them, at least on the issue of live streaming, it appears that Justice Isa is winning over judges to his side. A 5-5 decision in the review petition could force CJ Gulzar Ahmed to get involved as the referee judge – an involvement that he has so far tried to avoid.

When CJ barred Qazi Faez Isa from hearing Imran Khan’s cases

The proceedings of Qazi Faez Isa’s review petition and the application to permit the live streaming of these hearings cannot be looked at in isolation. Earlier this year, on February 3, a two-member bench comprising Justice Qazi Faez Isa and Justice Maqbool Baqir had issued notices to federal and provincial governments over news about possible issuance of Rs 500 million to each MNA. The 5-member bench constituted by CJ Gulzar Ahmed to hear the case suspiciously excluded Justice Maqbool Baqir, although it was reported that the honourable judge was on leave. On February 11, the case was disposed of after an assurance by the Attorney General and the advocates general of the four provincial governments that no such issuance of funds was under consideration. However, a written order authored by CJ Gulzar Ahmed himself noted that Justice Qazi Faez Isa "should not hear matters involving the prime minister". The chief justice argued that since Justice Isa had filed a petition against PM Imran Khan in his personal capacity, it "would not be proper" for the former to hear cases involving the PM in order "to uphold the principle of un-biasness and impartiality".

This was again a surprising development. Senior court reporter Hasnaat Malik in his story for Express Tribune noted that a 12-judge full court of the Supreme Court had held in 1989 that “one set of judges of a constituted Bench of Supreme Court, cannot issue a direction to the other set of Judges or any of the Judges of the Bench, not to associate themselves or himself in hearing of a matter”. Furthermore, Justice Qazi Faez Isa was not even given the copy of the judgment before it was released to the media. He expressed ‘shock’ at media knowing about this order since as a member of the bench he should not only have received a copy, the verdict wouldn’t have been final without his signatures on it.

Mr and Mrs Isa have also filed a petition in Supreme Court accusing the Registrar of manipulating things on government’s behest. They accuse the registrar of deliberately delaying the review case so that Justice Manzoor Malik retires before the conclusion of the case. Manzoor Malik retires on April 30th and the bench will have to be reconstituted if the case doesn’t reach a conclusion by then.

Judges on the bench exchange barbs during the hearing

On 20th of April when Justice Munib Akhtar ordered Mrs Sarina Isa to read from her statement on June 18, Asad Ali Toor reported for Naya Daur Urdu that Mrs Isa didn’t have the copy of the statement and said she stood by every word she had said back then but couldn’t read out her statement because other judges were telling her to finish her arguments as early as possible. Justice Mansoor Ali Shah and Justice Maqbool Baqir told her to carry on with her arguments, only to get snubbed by their junior Justice Munib Akhtar who said he didn’t want any interruption from other judges on the bench. When Qazi Faez Isa came to his wife’s rescue and objected that the judges do not have the right to dictate how a petitioner must pursue their case, Munib Akhtar told him he needed no dictation from anyone. “You start reading your statement now or I’ll read it myself”. By this time, Sarina Isa was already in tears. Justice Mazhar Alam Miankhel had had enough. He told Sarina Isa that the bench had read her statement and there was no need for her to read it again. Justice Maqbool Baqir concurred. Justice Umar Ata Bandial apologised to Mrs Isa for what she was going through. Justice Munib Akhtar also apologised saying he did not mean to harass her.

Things went from bad to worse when on April 22, Justice Munib Akhtar again snubbed J. Maqbool Baqir who was telling Deputy attorney general to conclude his remarks. Justice Sajjad Ali Shah joined him, telling Justice Bandial that J. Maqbool Baqir was welcome to leave if he was in some kind of a hurry. Justice Maqbool Baqir threw his pen on the desk, saying ‘this is too much’. And left. Justice Umar Ata Bandial had to suspend the hearing for 10 minutes to get things back on track.

‘Judges are doubting each other’s sincerity’

Salahuddin Ahmed, the president of Sindh High Court Bar Association, said it was something never witnessed before. “It is unprecedented. Disagreements are normal. In Iftikhar Chaudhry’s case too, the opinion of the bench was divided but despite a split decision, we didn’t see any barbs being exchanged. The only time the hostilities came to this level was in 1997 when Chief Justice Sajjad Ali Shah was ousted”, he said.

When asked what could be the cause behind these hostilities, Salahuddin said the judges seemed to have lost trust in each other.

“There are basically two problems. First is Qazi Faez Isa case itself. There’s a perception that the entire case against him is being manufactured by the establishment; that the latter wants him out. Some of the judges have clearly said they think as much. They have strong feelings about this. If we look at things from their point of view, it was obviously unprecedented to quash the reference but send the case to FBR. The judges, it appears, don’t trust each other anymore. Disagreement is natural but there has to be this basic trust that the other judges on the bench are sincerely interpreting the question according to their understanding. Right now, judges are doubting each other’s sincerity.”

He added that the J. Qazi Faez Isa's case had also divided the court because it had been unnecessarily prolonged. “Justice Umar Ata Bandial, who’s also heading this bench, said the other day that there was no element of corruption involved in this case. It has also been established that Mrs Sarina Isa had transferred the amount from one of her bank accounts in Karachi to another of hers in England. So there’s no question of money-laundering either. What is the case then? The question they should be asking themselves is that if they all agree on these two basic facts of this case, is it really worth tearing the court apart?”

‘The matter should have been closed’

Barrister at Law & advocate Supreme Court of Pakistan, Amber Darr, is in complete agreement with Salahuddin Ahmed on this case. She says that in deciding a matter the courts are constrained by the prayer made in the matter. In doing so they can direct executive authorities to take such actions as may be necessary. “The Supreme Court directing the FBR to initiate proceedings against Mrs. Isa was highly irregular. It is important to emphasize, however, that this kind of judicial overreach is not new, and can be traced back to the judicial overreach of the Chaudhry court. What is irregular in this matter is that the prayers in the original reference were with regard to Justice Isa’s failure to declare the properties. Once it had been established that the properties did not belong to him, the matter should have been closed”.

Darr added that Justice Bandial’s very obvious show of displeasure at Mr. Isa’s arguments was irregular. “A judge is bound by the law to give patient hearing to the arguments of litigants rather than to show impatience of displeasure. It would have been bad enough if Justice Bandial had done this to any litigant rather than to a brother judge. In adopting this attitude Justice Bandial has revealed that he may not hear this case at any rate. "Justice Bandial’s behaviour does not behove a senior judge of the apex court and I can only hope that the Chief Justice will have a conversation with him in this regard", she added.

Qadir blames the ‘failure to strictly follow the rules for the appointment of judges’ after Iftikhar Chaudhry’s reinstatement ‘through an executive order, not in a legal manner’ for the divisions in the higher judiciary. He added that bench and the bar are supposed to keep a check on each other but after lawyers’ movement, these checks and balances have been impacted. “It has not only damaged the reputation of the bench but also the integrity of the lawyers”, he said.

‘The perception that judges are being manipulated is unavoidable’

When asked for his view, the Vice Chariman of Pakistan Bar Council was scathing in his criticism. “I think this division in the Supreme Court is for difference of opinion among judges. Justice Bandial is following a conservative line while Justice Baqar is an independent and people’s judge”, he said.

Salahuddin Ahmed couldn’t disagree. The perception of being manipulated by politics is impossible to avoid. “The reference against J. Qazi Faez Isa came after his Faizabad Dharna verdict. Everyone knows it’s a consequence of that decision. This case is so obvious, even the pro-government people admit that it’s a politically motivated case”, he said.

Amber Darr adds that the ‘the issue here is not why the President sent a reference but the manner in which it was done. Under Article 209(5) of the Constitution of Pakistan, the President has the power to file a reference against a sitting judge of the Supreme Court of Pakistan if he is of the view that the judge may be incapable of properly performing the duties of his office by reason of physical or mental incapacity; or may have been guilty of misconduct.’

“The fact that the contents of this reference were not made available to Justice Isa is entirely unsupportable. It is a well-established principle of law that a man must know the case against him—the fact that the legal advisors of the President, the Attorney General or even the judges did not speak against this, is what renders the entire exercise suspect—almost as though the plan was to catch him unawares,” Darr added.

Darr also said that ‘Justice Isa’s case has tarnished the image of Supreme Court enjoyed in the eyes of the public. It has revealed the fault lines and the cracks in the edifice of the very institution that is entrusted with the delicate task of administering justice amongst the people. After the restoration of the former Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry in 2007, there was tremendous hope that the judiciary had left behind the era of deference to the executive and embarked firmly on the road of independence. It is sad to see that not only has this not been the case, but the judiciary appears to have become more inventive in its deference. She went on to add that "the greatest damage is not to the Supreme Court but to the very institution of justice in the country—this affair has further reduced the confidence of the ordinary person in the ability of the judiciary to grant justice and it will be a very long time before this will be restored."

When asked how these divisions among the judges would affect public’s trust in the judicial system, Salahuddin Ahmed also said it was going to be detrimental. “When the perception of judges being influenced is so strong, public trust in the system is bound to diminish”.

Brother [judges] versus brothers

The unfortunate strategy of pitting judges against their brother judges has an established history in Pakistan. It is most often a resort for the executive when seeking an outcome which is impeded by one or more less pliant judges.

Two examples of this partisanship can be considered from the past few decades. Each instance of manipulating the judiciary and intervening in its affairs forms part of a larger dark chapter.

The case against former prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto after he had been overthrown in the 1977 coup d'etat by General Zia-ul-Haq and others is illustrative of this 'strategy'. With the coup already having been given a legal justification of sorts under the now infamous “doctrine of necessity,” the Zia regime moved in for the kill, quite literally. In early September 1977, Bhutto was arrested and charged with ordering the murder of Muhammad Ahmed Khan Kasuri. However, Justice KMA Samdani dismissed the evidence presented and Bhutto walked free – much to the dismay of the military regime.

Justice Samdani was removed by the regime and the trial reopened in October 1977, with Maulvi Mushtaq Hussain having been elevated to the chief justice of the High Court for this purpose. Maulvi Mushtaq Hussain proceeded to deprive Bhutto of one level of appeal, making the LHC a trial court rather than allowing the trial to begin in the lower courts. In March 1978, after a highly controversial process, Bhutto was sentenced to death.

Begum Nusrat Bhutto, wife of the ousted Prime Minister, appealed to the Supreme Court in May 1978, where Chief Justice Yaqub Ali Khan's independence caused a new challenge for the military regime: he admitted the petition just three days before his own retirement. Knowing that out of 9 judges hearing the appeal, 5 were likely to favour Bhutto, the regime resorted to direct intervention. The case was deliberately adjourned until July 1978, so that Justice Qaisar Khan could retire and be removed from the list of 5. Another judge fell ill by this time, permitting the balance to tilt against Bhutto, with only 3 judges left who were willing to overturn the LHC verdict. The appeal failed and Bhutto was eventually hanged. This event is now widely referred to as a “judicial murder.”

A second and more blatant instance of such manipulation of the judiciary occurred during then Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif's tussle with Chief Justice of Pakistan Sajjad Ali Shah.

The PMLN government of that time was successful in dividing the senior-most judiciary into two hostile camps. A three-member bench of the Supreme Court led by Chief Justice Sajjad Ali Shah suspended the operation of the 13th Amendment to restore the powers of the president to dissolve the National Assembly. This verdict was set aside within minutes – by another 10-member bench of the apex court! Even though it had received no formal petition, the second bench led by Justice Saeeduzzaman Siddiqui granted a stay against the order of the Chief Justice.

The rebel judges led by Justice Saeeduzzaman Siddiqui refused to recognise Justice Sajjad Shah as their chief justice. Questioning the validity of the appointment of the Chief Justice, a two-member Quetta bench of the Supreme Court decided against Justice Sajjad Ali Shah. With his appointment held in abeyance by the Quetta bench, the Chief Justice responded by declaring this to be lacking lawful authority. A Peshawar bench of the Supreme Court, however, upheld the decision of the Quetta bench.

The bitter crisis brought Pakistan's political and judicial history to one of its lowest points ever: in November 1997, as the Chief Justice heard a case against the prime minister for contempt of court, the sitting government organised mobs to storm the court while it was in session – all in an attempt to have the hearing adjourned.

His brother judges removed Chief Justice Sajjad Ali Shah from his position in December 1997.

“Questions about the partisanship of the Pakistani judiciary have been rife as far back as the Maulvi Tamizuddin Khan case when the judiciary first allowed a military takeover on the basis of the doctrine of necessity,” says Amber Darr. “The Lawyers’ Movement of 2007 was a blip in the history of judicial deference to the military-executive. What we are witnessing now is the aftermath of the blip.”

But now Judges do take a stand

Today, the echoes of these past episodes of tailoring the judiciary for the purposes of the executive reverberates as Justice Qazi Faez Isa faces his own set of challenges due to the perception that he had been too independent of the executive and other power centres.

But Amber Darr sees a ray of hope in the fact that some of the judges have taken a stand. “It is interesting to note that there are some judges now who are willing to take a stand against the executive. This means that rather than bemoaning the judges who are deferential to the executive we should be focusing our observation on those that are now willing to take a stand against it.”

Shehbaz Sharif's bail case and the ongoing trial of Justice Qazi Faez Isa have only laid bare the divisions in the courts and most independent jurists hold that as a vital pillar of the state, the judiciary would need to close ranks and protect the public interest as mandated by the Constitution.

On April 13, Lahore High Court’s (LHC) two-member bench comprising Justice Sardar Muhammad Sarfraz Dogar and Justice Asjad Javed Ghural granted Pakistan Muslim League – Nawaz (PMLN) president Shehbaz Sharif bail in the money-laundering case. While reading the short order, the court reader announced that Sharif’s bail application had been accepted against two bail bonds worth Rs 5 million each, and that the detailed judgment was to be issued later.

However, it turned out later that Justice Ghural had refused to sign the short order written by his colleague Justice Dogar. The next day, Justice Ghural came to the High Court, heard cases but did not go to the division bench resulting in cancellation of the cause list of the day. On April 16, reports started circulating that PMLN leaders kept sitting outside Justice Ghural’s chamber throughout the day but the learned judge left for home without signing the judgment. On Sunday, finally, Justice Ghural wrote his decision denying bail to the former Punjab Chief Minister and also narrated the whole incident that had transpired on April 13. In his decision, he wrote how he disagreed with the ‘observations, reasoning and the conclusion handed down by the learned brother’ Justice Sarfraz Dogar. He went on to add: “It is shocking for me to observe here that it has been mentioned in the beginning paragraph of the said order that ‘unanimous order qua grant of bail to the petitioner was announced’, which is against the ground reality. In fact, after hearing the parties, when my learned brother sought my consent qua allowing the petition, I refused … but surprisingly, my learned brother unilaterally announced his decision through his Naib Qasid granting bail to the petitioner.”

In his judgment, Justice Sarfraz Dogar laid out his version of the day’s events. “… after hearing learned counsel for the parties and going through the record, unanimous order qua grant of bail to the petitioner was announced, but subsequently when the short order for releasing of petitioner was place for signature before my learned brother (Mr. Asjad Javed Ghural, J), who then disclosed that he intends to give his dissenting view. Therefore, we are rendering separate orders and after completion of the same, matter shall be placed before the Hon’ble Chief Justice for nomination of a Referee Judge.”

This was an unprecedented situation. Later, the LHC Chief Justice Muhammad Qasim Khan formed a new three-member bench to examine the matter and Sharif was granted bail on April 23.

But the earlier fisaco has baffled legal experts as to how a disagreement between the judges blew up in full public view with one of the judges announcing a unanimous order while the other was writing a dissenting note.

‘This decision can damage the integrity of the court’

Former Attorney General Irfan Qadir says that this was an abnormal situation. Talking to anchor Kamran Khan on Dunya TV, Qadir said that it was unprecedented for a verdict to be changed, especially in higher courts, after being announced by the reader. “I can’t even remember a situation where judges disagreed on a bail matter. Generally, even if one of the judges considers the case doubtful and thinks the accused should be granted the bail, the other judge doesn’t resist that. In bail cases at least, this is not normal. I’m surprised myself and believe this decision can damage the integrity of the court. Let’s not forget the Supreme Court has already expressed its concerns regarding political engineering in such high profile political cases”, Qadir said.

He listed three things for a judge to consider in a bail case. “First, the judge should look at the merits of the case. Second, the judges review the medical condition of the petitioner. And third, in political cases, they must also see if the petitioner was being persecuted for the sake of political engineering. If we look at all these things, and the fact that order was announced in the court, how could they leave the matter without a conclusion? Once an announcement is made in the court, the order following it is not supposed to contradict it. Such a situation is looked at with suspicion. This is unusual. This should never happen,” he said.

‘This appeared dubious and out of the ordinary’

Pakistan’s Judiciary has always come under criticism for perceived partisanship and decisions influenced by exogenous factors. The Shehbaz Sharif Bail case is one such example, where a dissenting note was given 4 full days after release on bail order. Speaking to Naya Daur Media, Muhammad Zubair Umer, Nawaz Sharif’s spokesperson, argued that if one judge is overwhelmingly inclined to release the accused on bail, then it is commonly accepted practice for the other to follow suit. Naya Daur Media asked Zubair Umer about the possible reasons according to him behind an extremely late dissenting note. The former governor of Sindh province commented that while judicial history and past is littered with examples of decisions based on extra legal reasoning under various external influences, he was not fully aware as to why the dissenting note in this case had come after 4 days had elapsed. He admitted that this appeared dubious and out of the ordinary. However, he expressed confidence in the court for the matter to be adjudicated reasonably.

Divisions in the Supreme Court?

But such divisions within the bench are not just limited to the Lahore High Court. An even more intriguing situation is developing in Supreme Court where the fourth most senior judge of the apex court is currently pleading his case before a 10-member bench.

A presidential reference was filed against Justice Qazi Faez Isa — in line to become the chief justice on September 18, 2023, for 13 months — in May 2019. Although the 10-member bench had unanimously quashed the reference in its June 19, 2020 decision, 7 out of the 10 judges agreed that the assets of Justice Qazi Faez Isa’s wife Mrs Sarina Isa should be further investigated. Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) was directed to initiate an investigation into the assets and submit the report before Supreme Judicial Council within 75 days. Senior lawyer Babar Sattar had termed the decision ‘a complaint-in-waiting against Qazi Faez Isa to be taken up in 75 days’. Justice Isa for reasons obvious filed a review petition.

The petition is currently being heard by a 10-member bench headed by Justice Umar Ata Bandial, the senior most judge in Supreme Court after Chief Justice Gulzar Ahmed. An application seeking permission for live streaming the hearings of the review petition hearings was rejected by the bench in a 6-4 verdict. The judges who were in favour of live streaming included Justice Manzoor Malik, Justice Mazhar Alam Miankhel, Justice Mansoor Ali Shah and Justice Yahya Afridi. Justices Shah and Afridi have already given their verdict in Justice Qazi Faez Isa’s favour in the original decision. Now that Justice Manzoor Malik and Mazhar Alam Miankhel have also joined them, at least on the issue of live streaming, it appears that Justice Isa is winning over judges to his side. A 5-5 decision in the review petition could force CJ Gulzar Ahmed to get involved as the referee judge – an involvement that he has so far tried to avoid.

When CJ barred Qazi Faez Isa from hearing Imran Khan’s cases

The proceedings of Qazi Faez Isa’s review petition and the application to permit the live streaming of these hearings cannot be looked at in isolation. Earlier this year, on February 3, a two-member bench comprising Justice Qazi Faez Isa and Justice Maqbool Baqir had issued notices to federal and provincial governments over news about possible issuance of Rs 500 million to each MNA. The 5-member bench constituted by CJ Gulzar Ahmed to hear the case suspiciously excluded Justice Maqbool Baqir, although it was reported that the honourable judge was on leave. On February 11, the case was disposed of after an assurance by the Attorney General and the advocates general of the four provincial governments that no such issuance of funds was under consideration. However, a written order authored by CJ Gulzar Ahmed himself noted that Justice Qazi Faez Isa "should not hear matters involving the prime minister". The chief justice argued that since Justice Isa had filed a petition against PM Imran Khan in his personal capacity, it "would not be proper" for the former to hear cases involving the PM in order "to uphold the principle of un-biasness and impartiality".

This was again a surprising development. Senior court reporter Hasnaat Malik in his story for Express Tribune noted that a 12-judge full court of the Supreme Court had held in 1989 that “one set of judges of a constituted Bench of Supreme Court, cannot issue a direction to the other set of Judges or any of the Judges of the Bench, not to associate themselves or himself in hearing of a matter”. Furthermore, Justice Qazi Faez Isa was not even given the copy of the judgment before it was released to the media. He expressed ‘shock’ at media knowing about this order since as a member of the bench he should not only have received a copy, the verdict wouldn’t have been final without his signatures on it.

Mr and Mrs Isa have also filed a petition in Supreme Court accusing the Registrar of manipulating things on government’s behest. They accuse the registrar of deliberately delaying the review case so that Justice Manzoor Malik retires before the conclusion of the case. Manzoor Malik retires on April 30th and the bench will have to be reconstituted if the case doesn’t reach a conclusion by then.

Judges on the bench exchange barbs during the hearing

On 20th of April when Justice Munib Akhtar ordered Mrs Sarina Isa to read from her statement on June 18, Asad Ali Toor reported for Naya Daur Urdu that Mrs Isa didn’t have the copy of the statement and said she stood by every word she had said back then but couldn’t read out her statement because other judges were telling her to finish her arguments as early as possible. Justice Mansoor Ali Shah and Justice Maqbool Baqir told her to carry on with her arguments, only to get snubbed by their junior Justice Munib Akhtar who said he didn’t want any interruption from other judges on the bench. When Qazi Faez Isa came to his wife’s rescue and objected that the judges do not have the right to dictate how a petitioner must pursue their case, Munib Akhtar told him he needed no dictation from anyone. “You start reading your statement now or I’ll read it myself”. By this time, Sarina Isa was already in tears. Justice Mazhar Alam Miankhel had had enough. He told Sarina Isa that the bench had read her statement and there was no need for her to read it again. Justice Maqbool Baqir concurred. Justice Umar Ata Bandial apologised to Mrs Isa for what she was going through. Justice Munib Akhtar also apologised saying he did not mean to harass her.

Things went from bad to worse when on April 22, Justice Munib Akhtar again snubbed J. Maqbool Baqir who was telling Deputy attorney general to conclude his remarks. Justice Sajjad Ali Shah joined him, telling Justice Bandial that J. Maqbool Baqir was welcome to leave if he was in some kind of a hurry. Justice Maqbool Baqir threw his pen on the desk, saying ‘this is too much’. And left. Justice Umar Ata Bandial had to suspend the hearing for 10 minutes to get things back on track.

‘Judges are doubting each other’s sincerity’

Salahuddin Ahmed, the president of Sindh High Court Bar Association, said it was something never witnessed before. “It is unprecedented. Disagreements are normal. In Iftikhar Chaudhry’s case too, the opinion of the bench was divided but despite a split decision, we didn’t see any barbs being exchanged. The only time the hostilities came to this level was in 1997 when Chief Justice Sajjad Ali Shah was ousted”, he said.

When asked what could be the cause behind these hostilities, Salahuddin said the judges seemed to have lost trust in each other.

“There are basically two problems. First is Qazi Faez Isa case itself. There’s a perception that the entire case against him is being manufactured by the establishment; that the latter wants him out. Some of the judges have clearly said they think as much. They have strong feelings about this. If we look at things from their point of view, it was obviously unprecedented to quash the reference but send the case to FBR. The judges, it appears, don’t trust each other anymore. Disagreement is natural but there has to be this basic trust that the other judges on the bench are sincerely interpreting the question according to their understanding. Right now, judges are doubting each other’s sincerity.”

He added that the J. Qazi Faez Isa's case had also divided the court because it had been unnecessarily prolonged. “Justice Umar Ata Bandial, who’s also heading this bench, said the other day that there was no element of corruption involved in this case. It has also been established that Mrs Sarina Isa had transferred the amount from one of her bank accounts in Karachi to another of hers in England. So there’s no question of money-laundering either. What is the case then? The question they should be asking themselves is that if they all agree on these two basic facts of this case, is it really worth tearing the court apart?”

‘The matter should have been closed’

Barrister at Law & advocate Supreme Court of Pakistan, Amber Darr, is in complete agreement with Salahuddin Ahmed on this case. She says that in deciding a matter the courts are constrained by the prayer made in the matter. In doing so they can direct executive authorities to take such actions as may be necessary. “The Supreme Court directing the FBR to initiate proceedings against Mrs. Isa was highly irregular. It is important to emphasize, however, that this kind of judicial overreach is not new, and can be traced back to the judicial overreach of the Chaudhry court. What is irregular in this matter is that the prayers in the original reference were with regard to Justice Isa’s failure to declare the properties. Once it had been established that the properties did not belong to him, the matter should have been closed”.

Darr added that Justice Bandial’s very obvious show of displeasure at Mr. Isa’s arguments was irregular. “A judge is bound by the law to give patient hearing to the arguments of litigants rather than to show impatience of displeasure. It would have been bad enough if Justice Bandial had done this to any litigant rather than to a brother judge. In adopting this attitude Justice Bandial has revealed that he may not hear this case at any rate. "Justice Bandial’s behaviour does not behove a senior judge of the apex court and I can only hope that the Chief Justice will have a conversation with him in this regard", she added.

Qadir blames the ‘failure to strictly follow the rules for the appointment of judges’ after Iftikhar Chaudhry’s reinstatement ‘through an executive order, not in a legal manner’ for the divisions in the higher judiciary. He added that bench and the bar are supposed to keep a check on each other but after lawyers’ movement, these checks and balances have been impacted. “It has not only damaged the reputation of the bench but also the integrity of the lawyers”, he said.

‘The perception that judges are being manipulated is unavoidable’

When asked for his view, the Vice Chariman of Pakistan Bar Council was scathing in his criticism. “I think this division in the Supreme Court is for difference of opinion among judges. Justice Bandial is following a conservative line while Justice Baqar is an independent and people’s judge”, he said.

Salahuddin Ahmed couldn’t disagree. The perception of being manipulated by politics is impossible to avoid. “The reference against J. Qazi Faez Isa came after his Faizabad Dharna verdict. Everyone knows it’s a consequence of that decision. This case is so obvious, even the pro-government people admit that it’s a politically motivated case”, he said.

Amber Darr adds that the ‘the issue here is not why the President sent a reference but the manner in which it was done. Under Article 209(5) of the Constitution of Pakistan, the President has the power to file a reference against a sitting judge of the Supreme Court of Pakistan if he is of the view that the judge may be incapable of properly performing the duties of his office by reason of physical or mental incapacity; or may have been guilty of misconduct.’

“The fact that the contents of this reference were not made available to Justice Isa is entirely unsupportable. It is a well-established principle of law that a man must know the case against him—the fact that the legal advisors of the President, the Attorney General or even the judges did not speak against this, is what renders the entire exercise suspect—almost as though the plan was to catch him unawares,” Darr added.

Darr also said that ‘Justice Isa’s case has tarnished the image of Supreme Court enjoyed in the eyes of the public. It has revealed the fault lines and the cracks in the edifice of the very institution that is entrusted with the delicate task of administering justice amongst the people. After the restoration of the former Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry in 2007, there was tremendous hope that the judiciary had left behind the era of deference to the executive and embarked firmly on the road of independence. It is sad to see that not only has this not been the case, but the judiciary appears to have become more inventive in its deference. She went on to add that "the greatest damage is not to the Supreme Court but to the very institution of justice in the country—this affair has further reduced the confidence of the ordinary person in the ability of the judiciary to grant justice and it will be a very long time before this will be restored."

When asked how these divisions among the judges would affect public’s trust in the judicial system, Salahuddin Ahmed also said it was going to be detrimental. “When the perception of judges being influenced is so strong, public trust in the system is bound to diminish”.

Brother [judges] versus brothers

The unfortunate strategy of pitting judges against their brother judges has an established history in Pakistan. It is most often a resort for the executive when seeking an outcome which is impeded by one or more less pliant judges.

Two examples of this partisanship can be considered from the past few decades. Each instance of manipulating the judiciary and intervening in its affairs forms part of a larger dark chapter.

The case against former prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto after he had been overthrown in the 1977 coup d'etat by General Zia-ul-Haq and others is illustrative of this 'strategy'. With the coup already having been given a legal justification of sorts under the now infamous “doctrine of necessity,” the Zia regime moved in for the kill, quite literally. In early September 1977, Bhutto was arrested and charged with ordering the murder of Muhammad Ahmed Khan Kasuri. However, Justice KMA Samdani dismissed the evidence presented and Bhutto walked free – much to the dismay of the military regime.

Justice Samdani was removed by the regime and the trial reopened in October 1977, with Maulvi Mushtaq Hussain having been elevated to the chief justice of the High Court for this purpose. Maulvi Mushtaq Hussain proceeded to deprive Bhutto of one level of appeal, making the LHC a trial court rather than allowing the trial to begin in the lower courts. In March 1978, after a highly controversial process, Bhutto was sentenced to death.

Begum Nusrat Bhutto, wife of the ousted Prime Minister, appealed to the Supreme Court in May 1978, where Chief Justice Yaqub Ali Khan's independence caused a new challenge for the military regime: he admitted the petition just three days before his own retirement. Knowing that out of 9 judges hearing the appeal, 5 were likely to favour Bhutto, the regime resorted to direct intervention. The case was deliberately adjourned until July 1978, so that Justice Qaisar Khan could retire and be removed from the list of 5. Another judge fell ill by this time, permitting the balance to tilt against Bhutto, with only 3 judges left who were willing to overturn the LHC verdict. The appeal failed and Bhutto was eventually hanged. This event is now widely referred to as a “judicial murder.”

A second and more blatant instance of such manipulation of the judiciary occurred during then Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif's tussle with Chief Justice of Pakistan Sajjad Ali Shah.

The PMLN government of that time was successful in dividing the senior-most judiciary into two hostile camps. A three-member bench of the Supreme Court led by Chief Justice Sajjad Ali Shah suspended the operation of the 13th Amendment to restore the powers of the president to dissolve the National Assembly. This verdict was set aside within minutes – by another 10-member bench of the apex court! Even though it had received no formal petition, the second bench led by Justice Saeeduzzaman Siddiqui granted a stay against the order of the Chief Justice.

The rebel judges led by Justice Saeeduzzaman Siddiqui refused to recognise Justice Sajjad Shah as their chief justice. Questioning the validity of the appointment of the Chief Justice, a two-member Quetta bench of the Supreme Court decided against Justice Sajjad Ali Shah. With his appointment held in abeyance by the Quetta bench, the Chief Justice responded by declaring this to be lacking lawful authority. A Peshawar bench of the Supreme Court, however, upheld the decision of the Quetta bench.

The bitter crisis brought Pakistan's political and judicial history to one of its lowest points ever: in November 1997, as the Chief Justice heard a case against the prime minister for contempt of court, the sitting government organised mobs to storm the court while it was in session – all in an attempt to have the hearing adjourned.

His brother judges removed Chief Justice Sajjad Ali Shah from his position in December 1997.

“Questions about the partisanship of the Pakistani judiciary have been rife as far back as the Maulvi Tamizuddin Khan case when the judiciary first allowed a military takeover on the basis of the doctrine of necessity,” says Amber Darr. “The Lawyers’ Movement of 2007 was a blip in the history of judicial deference to the military-executive. What we are witnessing now is the aftermath of the blip.”

But now Judges do take a stand

Today, the echoes of these past episodes of tailoring the judiciary for the purposes of the executive reverberates as Justice Qazi Faez Isa faces his own set of challenges due to the perception that he had been too independent of the executive and other power centres.

But Amber Darr sees a ray of hope in the fact that some of the judges have taken a stand. “It is interesting to note that there are some judges now who are willing to take a stand against the executive. This means that rather than bemoaning the judges who are deferential to the executive we should be focusing our observation on those that are now willing to take a stand against it.”

Shehbaz Sharif's bail case and the ongoing trial of Justice Qazi Faez Isa have only laid bare the divisions in the courts and most independent jurists hold that as a vital pillar of the state, the judiciary would need to close ranks and protect the public interest as mandated by the Constitution.