As the global community is still finding ways to contain the deadly spread of coronavirus (COVID-19), both Australia and New Zealand are effectively working towards “flattening the curve” of daily new cases of COVID-19 infections. These two countries present concise case studies of effective tackling of the deadly pandemic not only for Pakistan but also for the rest of the world.

Both Australia and New Zealand are on the cusp of defeating the coronavirus pandemic, mainly due to a major factor; setting aside political differences. Since early March, when both the countries started taking measures to control the pandemic, one can hardly find statements of opposition parties in the media criticizing the ruling government. Instead, especially in Australia, the state premiers (Pakistan’s equivalent of Chief Ministers) have worked in cohesion with the federal government to devise and implement unified policies that are “non-political” in nature. Damien Cave, writing for the New York Times, explains the key to success for Australia and New Zealand in the following words:

Whether they get to zero or not, what Australia and New Zealand have already accomplished is a remarkable cause for hope. Scott Morrison of Australia, a conservative Christian, and Jacinda Ardern, New Zealand’s darling of the left, are both succeeding with throwback democracy — in which partisanship recedes, experts lead, and quiet coordination matters more than firing up the base.

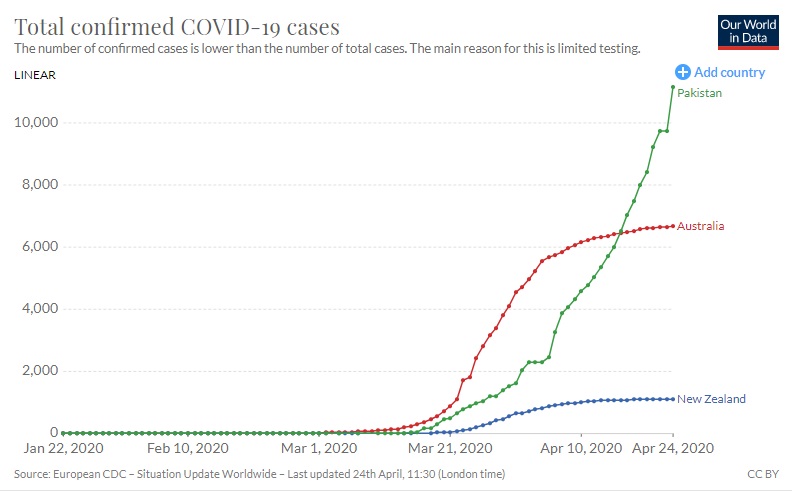

As of April 24, 2020, the total of COVID-19 cases in Australia, New Zealand and Pakistan stand at 6,667, 1,114, and 11,155 respectively. Even though the number of cases in both Australia and New Zealand is still on the lower side, when compared with other “western” states, their response has been somewhat swift, systematic and aggressive. Hence, Australia’s COVID-19 patient recovery rate stands at 80% (nearly 5,300 patients recovered), whereas New Zealand’s recovery rate stands at 75% (nearly 1,100 patients recovered). On the other hand, Pakistan’s patient recovery rate is less than 25% (nearly 2,700 recovered patients).

Fig 1: Total COVID-19 Confirmed Cases (Until April 24, 2020)

Australia has enforced strict measures for both its citizens and residents as well as international visitors and visa holders. On March 19, Australian PM Scott Morrison, without any prior warning, announced to close the country’s borders to all “non-citizens”. This meant that other than Australian citizens, permanent residents and those on special status visas, no one was allowed to enter the country after the PM’s announcement.

At the moment, about 10 per cent of Australians who have caught the virus don’t know how they got it, which is a sign of community spread. Most of the remaining cases, as reported by the government, have come from “foreigners” or Australians entering the country from overseas.

Moreover, Australia has also imposed a strict quarantine policy for all citizens and permanent residents arriving in Australia. The Department of Home Affairs, in that regard, says that:

All travellers arriving in Australia must undertake a mandatory 14-day quarantine at designated facilities (for example, a hotel), in their port of arrival.

For international citizens in Australia, the government suggests:

Due to the current situation in Australia due to COVID-19, including state and territory border restrictions, business closures and social distancing requirements, all international visitors are encouraged to depart if it is possible to do so.

Similarly, New Zealand, which is one of few countries to have effectively contained the spread of COVID-19 in recent days, has also implemented an “Alert Level 4 – Eliminate” for the pandemic. Level 4 Alert implies that “it is likely that the disease is not contained”. According to Michael Baker and Nick Wilson, writing for The Guardian, this “elimination approach” by New Zealand is different from the “mitigation” approach of managing the “pandemic influenza”. According to them:

With mitigation, the response is increased as the pandemic progresses, and more intensive interventions such as school closures are often held in reserve to “flatten the peak”. By contrast, disease elimination partly reverses the sequence by using vigorous interventions early to interrupt disease transmission.

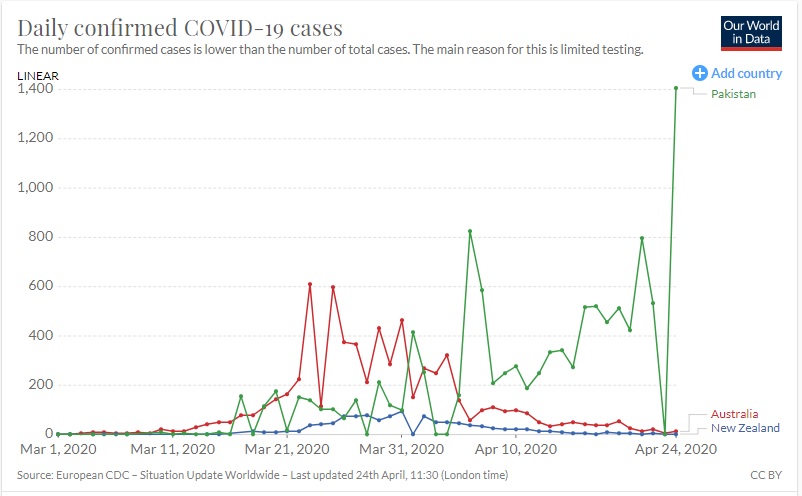

It is due to this aggressive approach that the number of daily new cases in both Australia and New Zealand is steadily falling as can be seen in Figure 2 below. The graph also shows how both these countries have nearly flattened the curve of daily new cases, unlike Pakistan, which is still recording high numbers since the beginning of April.

Fig 2: Daily COVID-19 Confirmed Cases (Until April 24, 2020)

A major take away from both Australia and New Zealand is the fact that both the countries were able to implement an early lock-down, by not only enforcing social distancing measures but also recommending that all non-essential workers work from home. Moreover, both countries also shut down their borders for international travel. By doing that, both the countries effectively controlled the transmission chain of the virus; buying essential time to implement their virus-elimination measures.

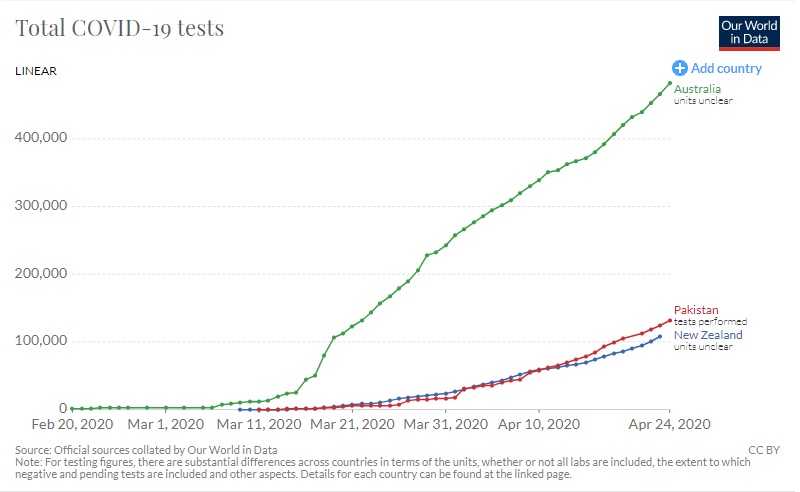

Also, when it comes to testing, we find that both Australia and New Zealand boast a higher number of “tests per 1,000 people” when compared to Pakistan. In terms of the total number of tests, Australia has so far conducted 482,000 tests, Pakistan 131,000 and New Zealand 108,000 COVID-19 tests (see below Figure 3).

Fig 3: Total Tests for COVID-19 (Until April 25, 2020)

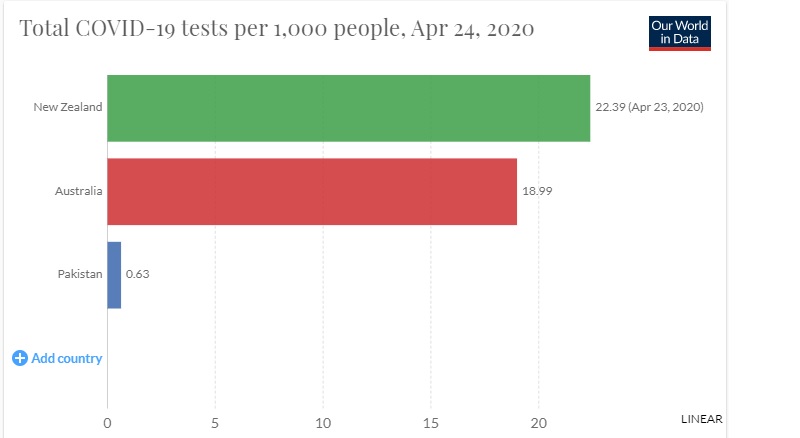

Therefore, where Australia and New Zealand’s “tests per 1,000 people” number stands at 22.39 and 18.99 respectively, Pakistan, on the other hand, has conducted a paltry 0.63 tests per 1000 people (see below Fig 4).

Fig 4: Total Tests per 1000 people (Until April 25, 2020)

Having discussed these measures, it is also worth noting that not all countries enjoy the luxury of pursuing the “elimination strategy”. Such a strategy can only work for countries that can effectively seal their borders and can bear the immense costs of testing and healthcare support. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that the European continent and the US followed the “mitigation” strategy, which not only overburdened the healthcare system but also resulted in high infection and transmission rates. In that regard, Pakistan’s decision of a “smart lockdown” might carry some weight. It is also worth noting that even with such strict measures, most businesses in Australia have remained open; as long as they implement social distancing measures. However, countries like Australia and New Zealand can afford to keep businesses open as the population, in general, has higher awareness levels and regard for laws compared to Pakistan.

Even with such complications, a major lesson for Pakistan from Australia and New Zealand’s COVID-19 response is following a clear, concise and “non-political” policy. Both these countries, from the early rise in numbers of infections, were not only clear in their approach and policy actions, but the political parties avoided confrontation with each other. Even though Pakistan might not enjoy such favourable conditions – such as strong democratic structures, stable economy and easy to manage borders – it can still ensure that its “mitigation strategy” for containing the coronavirus pandemic is clear and well laid-out. Moreover, PM Imran Khan needs to take the lead and avoid a political conflict, which pits Sindh (and PPP) against the Federation. Only a clear “apolitical” policy and its implementation can, therefore, pull Pakistan out of this global health catastrophe that has claimed thousands of lives.

(Data Source: Our World in Data)