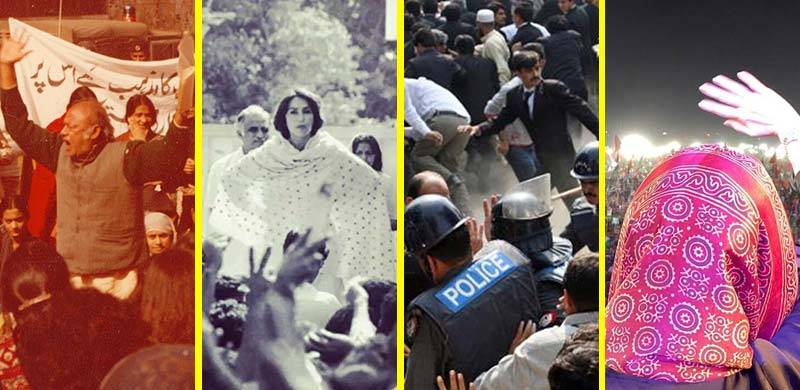

1: The Anti-Ayub Movement (1968-69)

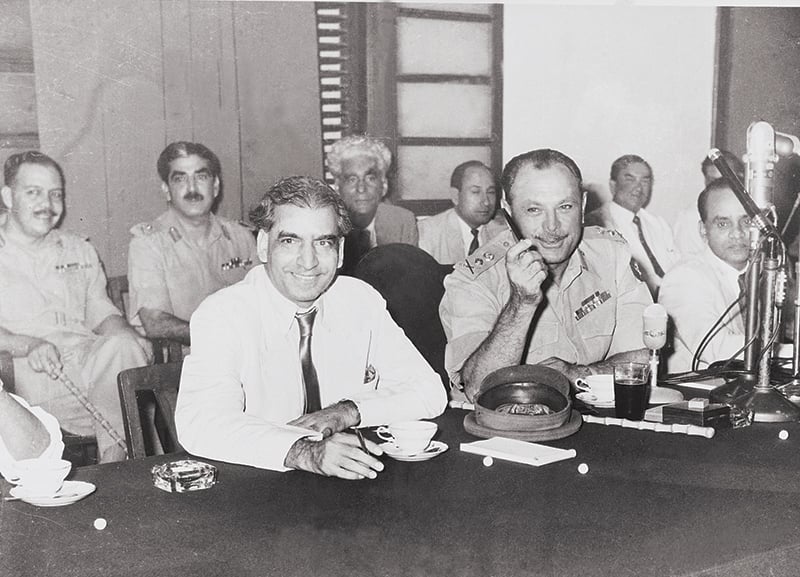

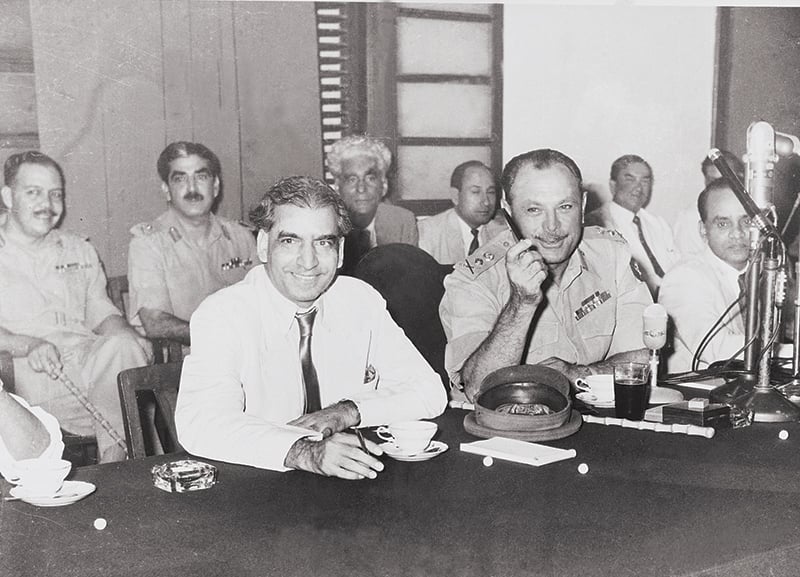

After a decade of political chaos, military chief Ayub Khan imposed the country’s first martial law in 1958. It was initially a popular coup which Ayub explained as a ‘revolution.’

With his regime’s economic policies and industrialisation project bearing fruit, Ayub remained firmly in the saddle till 1965. The opposition was weak and scattered.

After the war ended in a stalemate, fissures began to appear within the regime. The war negatively impacted the economy as well. The trickle-down effect that his economic policies were expected to create instead bolstered the fortunes of a handful of business groups. The gap between the rich and the poor widened, creating resentment.

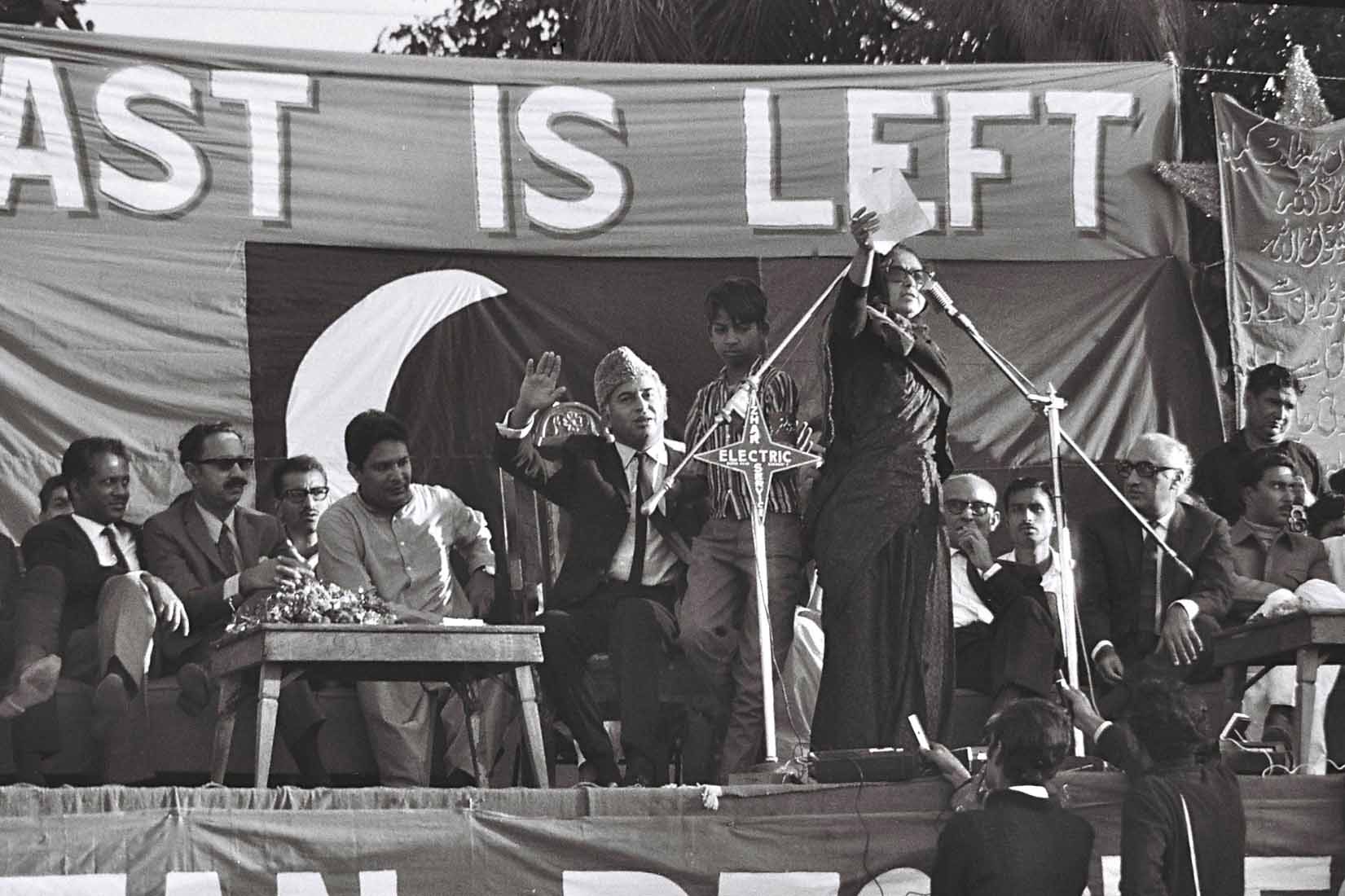

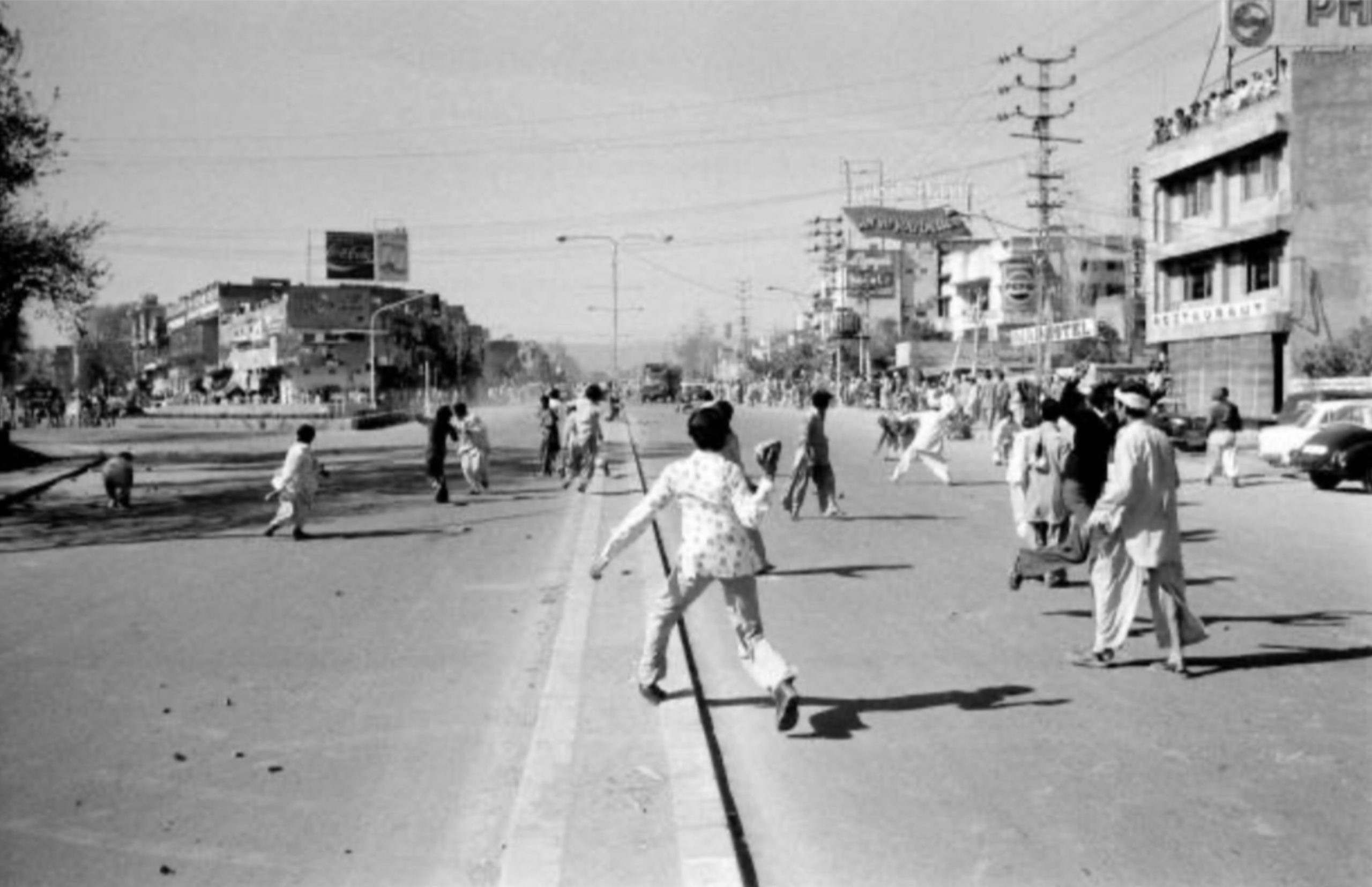

In 1968, the resentment came to the surface. A protest movement, mainly by left-wing student groups, turned violent and was soon joined by opposition parties, trade unions and eventually by small farmers and peasants.

It was a nationwide movement that triggered riots and strikes in both wings of the country, West Pakistan and East Pakistan. Leftist parties such as PPP and NAP demanded parliamentary democracy and a socialist economy, whereas in East Pakistan, the Bengali nationalist Awami League demanded provincial autonomy. Dozens were killed. Ayub’s political system was not inclusive, leaving large sections of the society feeling alienated.

Unable to stall the violence, Ayub resigned in March 1969. He handed over power to General Yahya Khan who imposed the country’s second martial law. He restored the provinces (abolished in 1955) and oversaw Pakistan’s first parliamentary elections held on adult franchise. Yahya resigned in December 1971 after Pakistan lost its eastern wing in a civil war. Power was transferred to civilian representatives after 13 years.

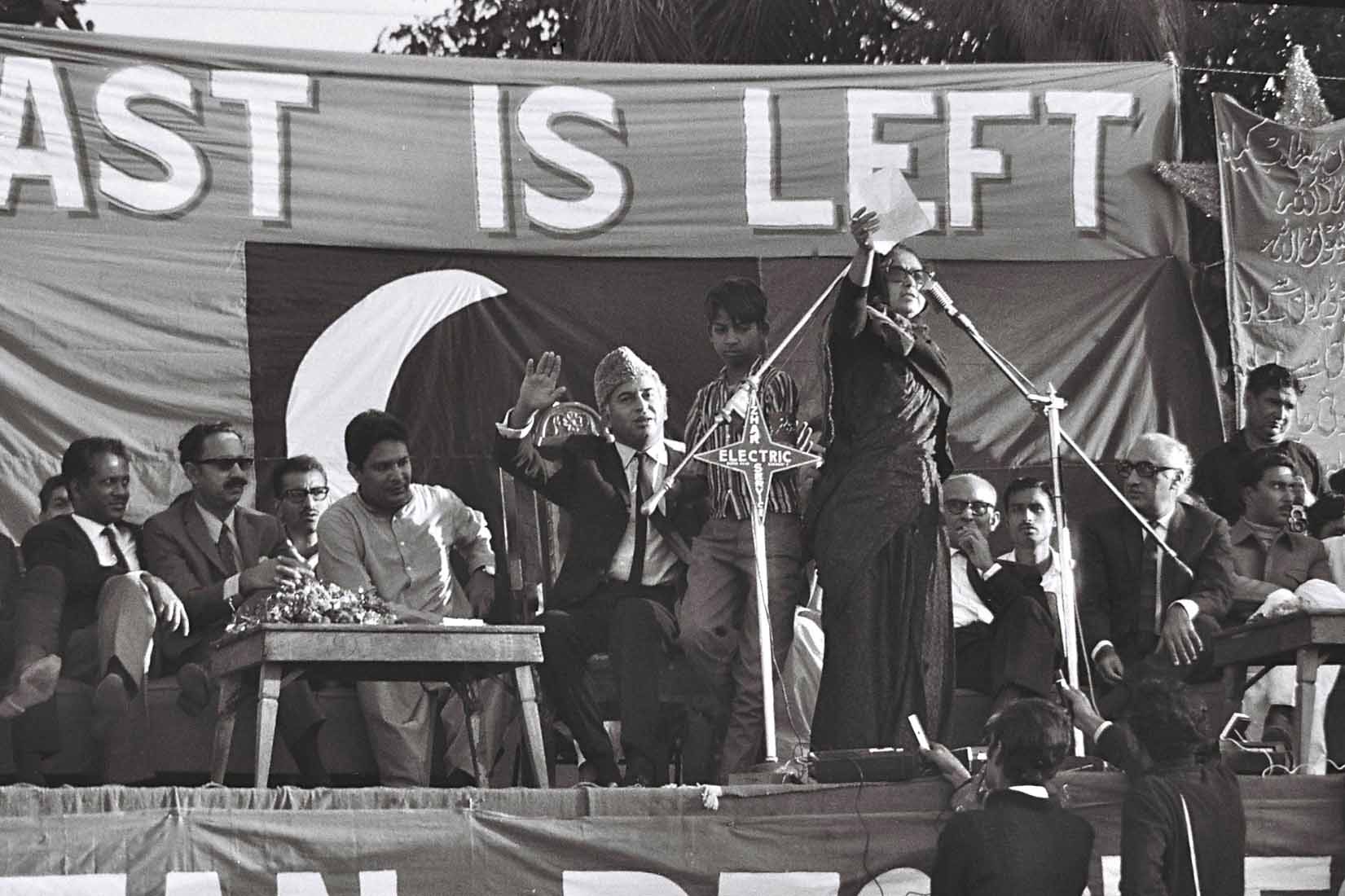

The PNA Movement, 1977

ZA Bhutto’s left-liberal PPP had swept the 1970 elections in West Pakistan’s two most populous provinces, Punjab and Sindh. After the departure of East Pakistan and Yahya, Bhutto became president and his government at once initiated economic reforms based on his party’s idea of socialism. Reforms were also introduced in the bureaucracy and the military.

After navigating his way through the economic and political fall-outs of the disastrous 1971 civil war and the loss of East Pakistan, Bhutto oversaw the passing of a new constitution in 1973 which turned Pakistan into a parliamentary democracy. Bhutto became prime minister. He neutralised a violent movement against the Ahmadiyya community by Islamic parties by agreeing to constitutionally oust the community from the fold of Islam.

By 1975, despite a Baloch nationalist insurgency, ZA Bhutto had largely overcome the many problems that his regime had faced in its first few years. But economy became a concern when the regime’s ‘socialist’ policies began to badly impact businesses and industry. This problem was compounded by an international oil crises which pushed up oil prices to unprecedented levels. By 1976, Bhutto was confident enough to call fresh elections in 1977, a year ahead of schedule. The opposition often described the Bhutto regime as ‘civilian dictatorship’ that used the police and the PM’s special security force, the FSF, to browbeat opposition outside and within his own party into submission.

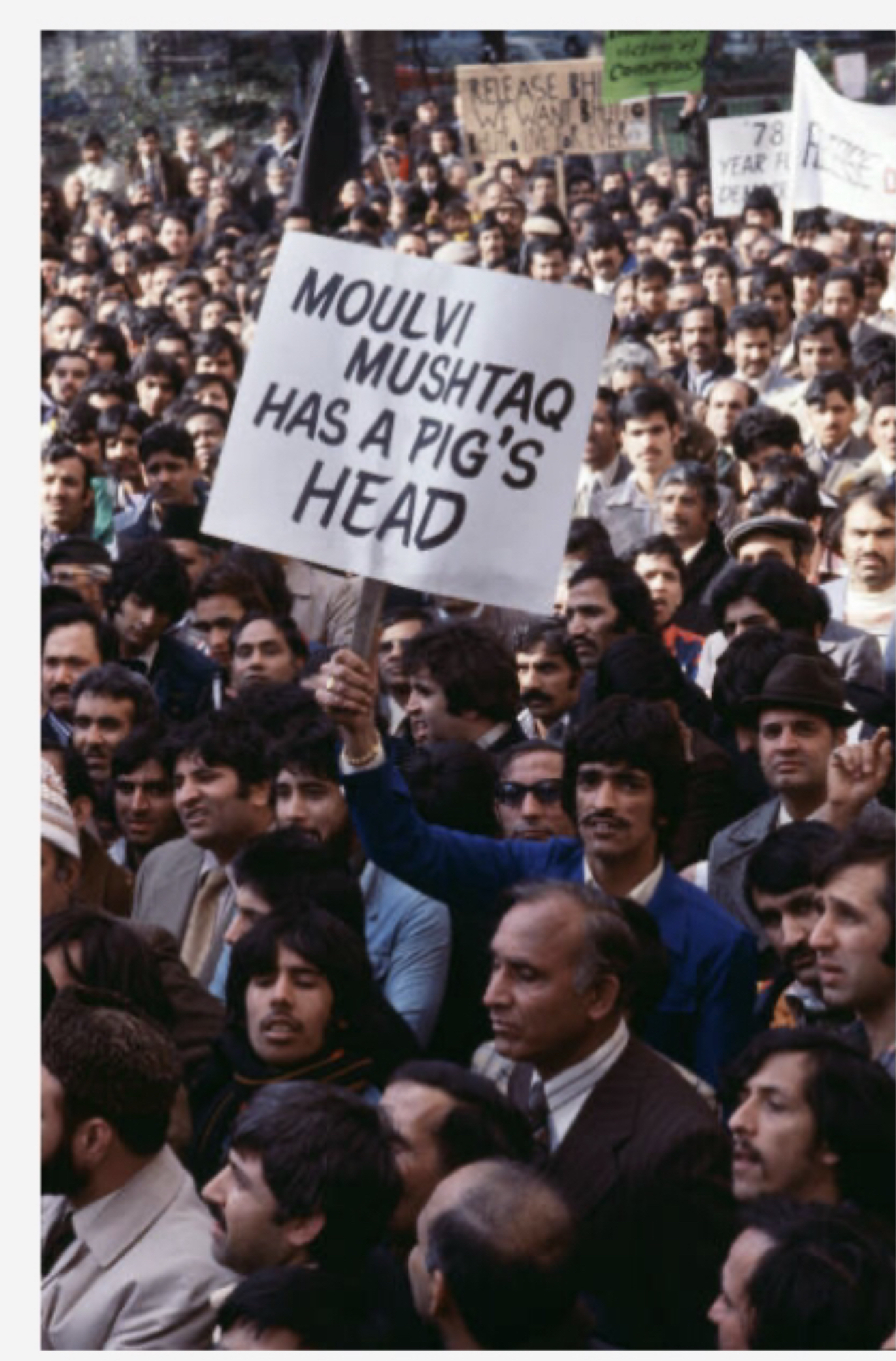

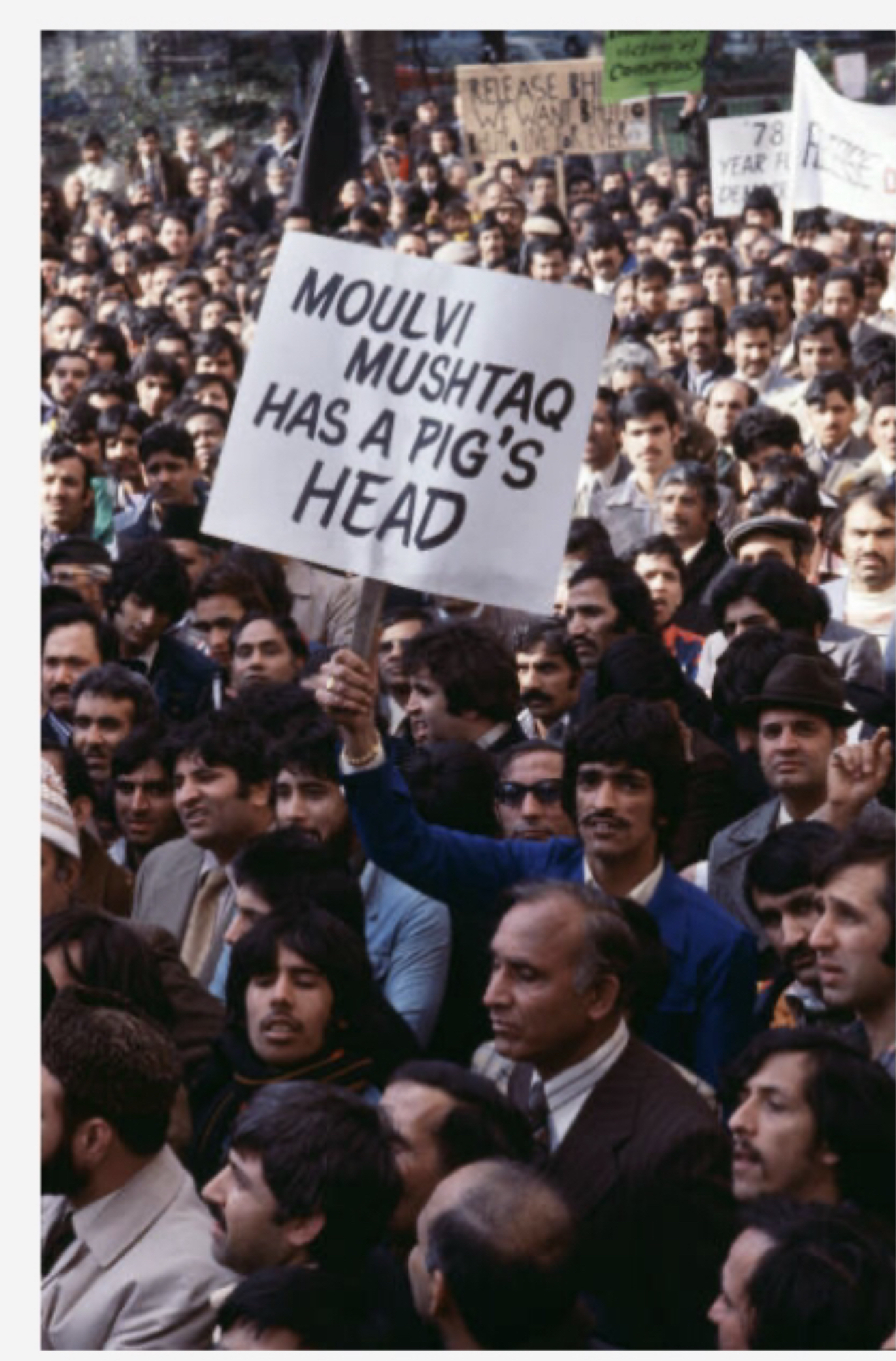

The PPP swept the election against PNA — an alliance of right-wing Islamic and centre-right parties demanding Islamic laws, deregulation of the economy and rollback of economic and land reforms. PNA cried foul, accusing the regime of rigging the polls and of political harassment.

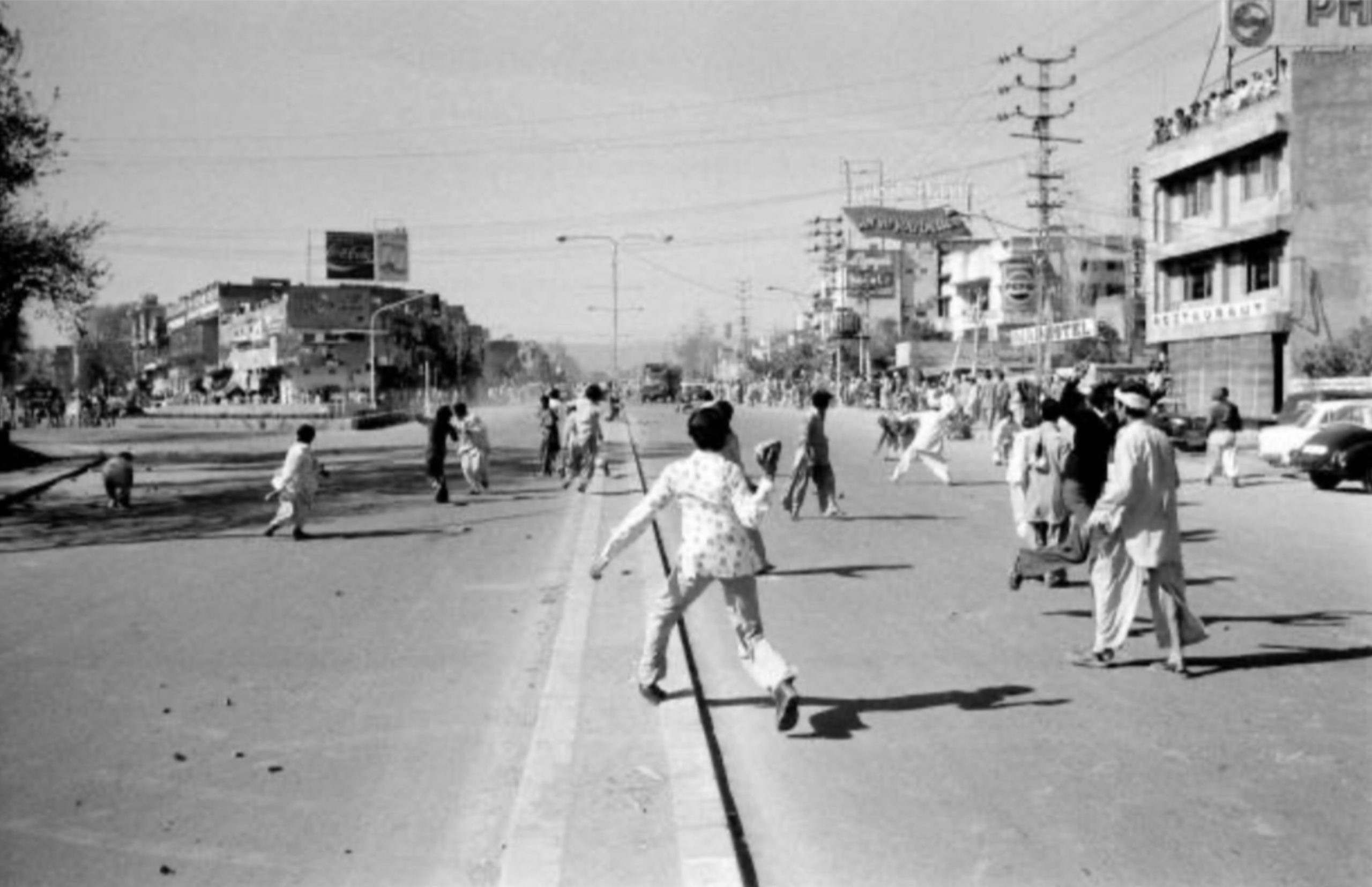

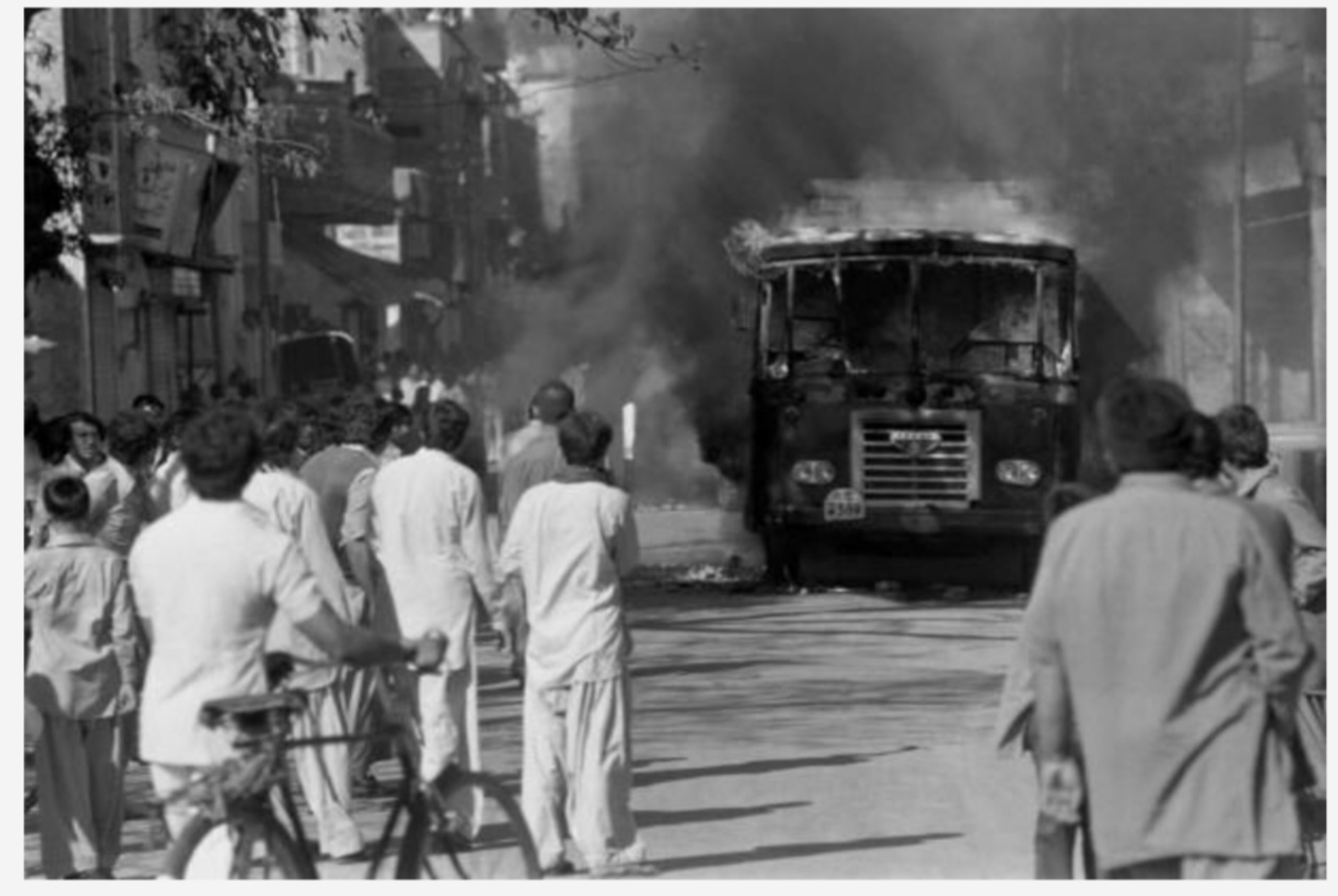

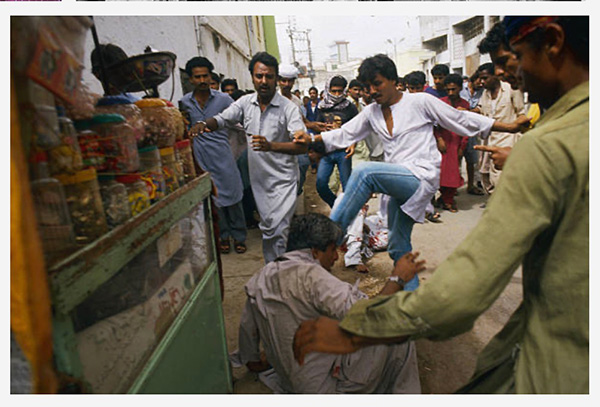

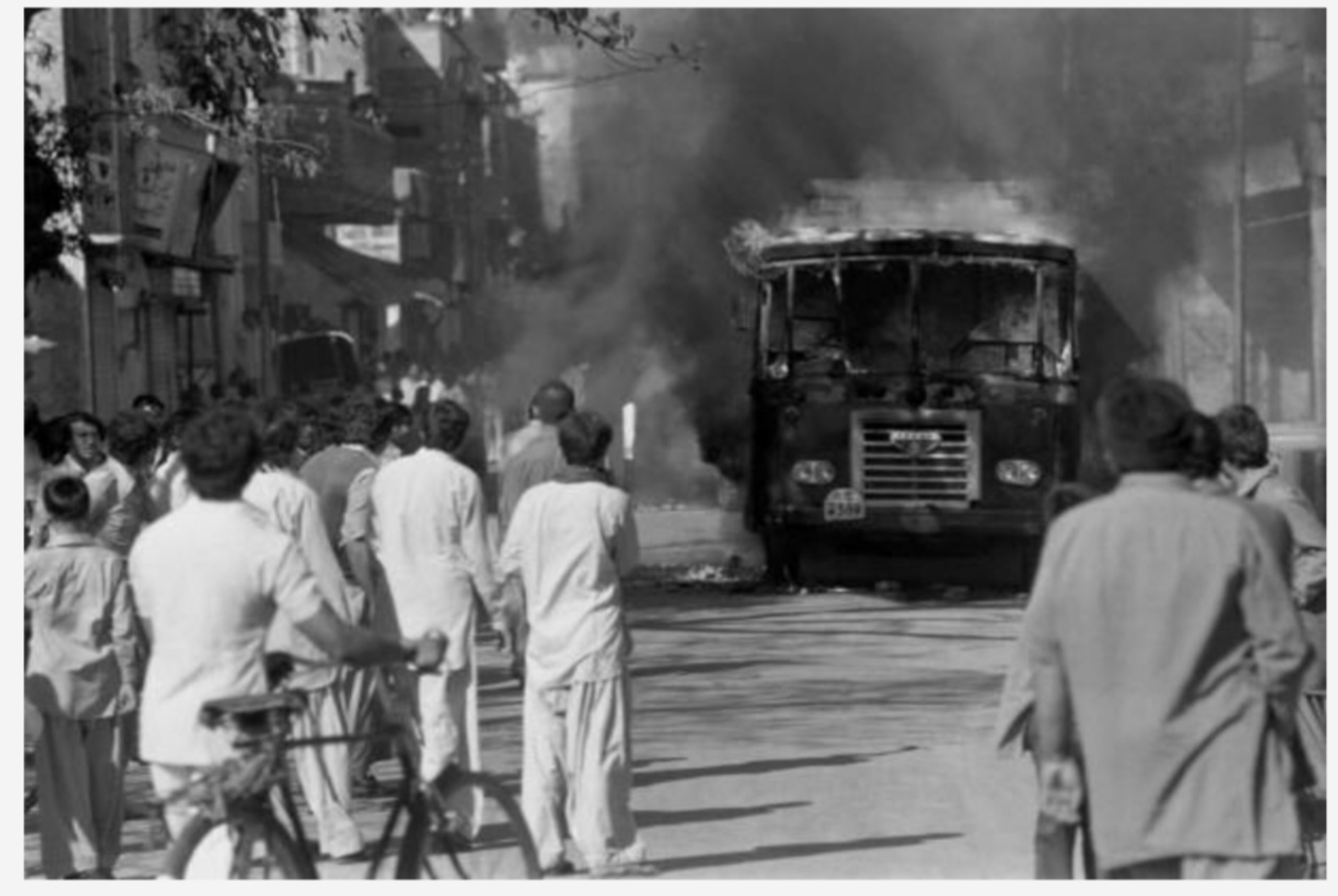

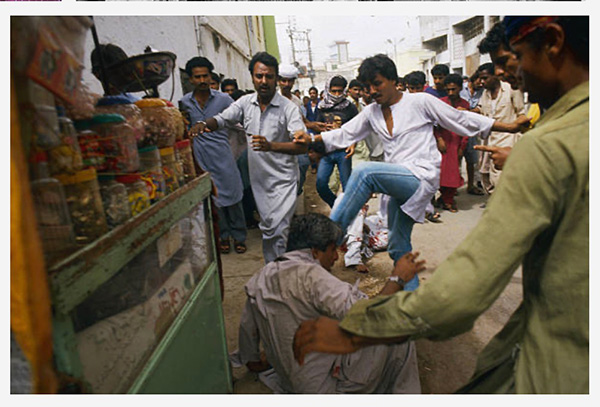

PNA called for countrywide protests that quickly turned violent, especially in Karachi and Lahore. Dozens were killed.

The violence intensified, as protesters set fire to homes of some PPP leaders, police stations, public buses, liquor stores, bars, cinemas and banks.

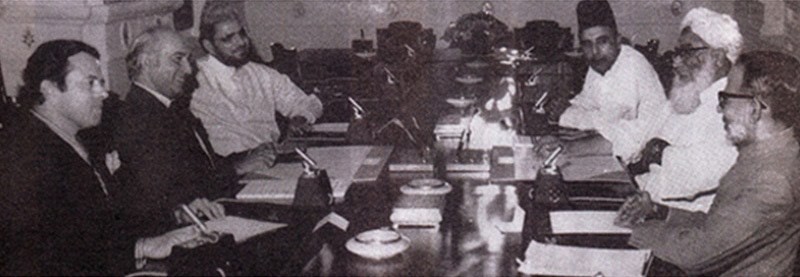

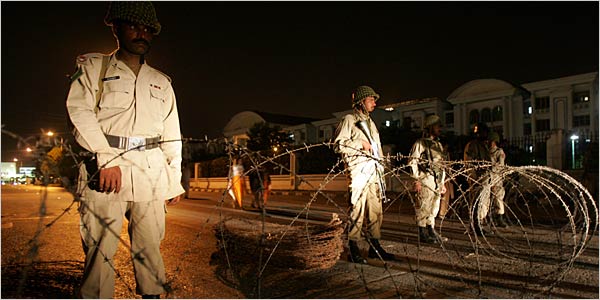

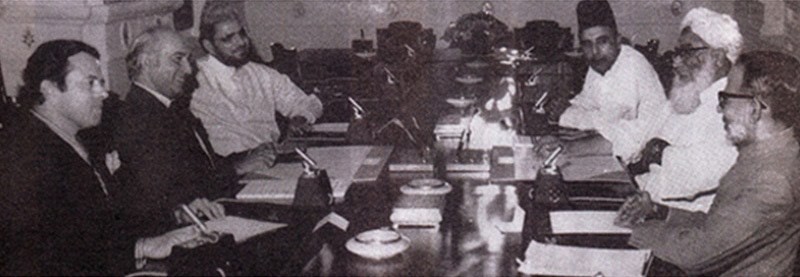

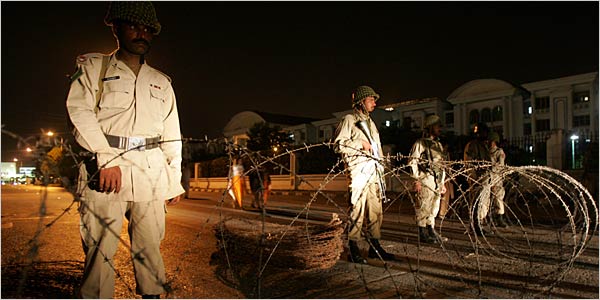

Bhutto was forced to negotiate with PNA leaders and agreed to accept many of their demands. But in July 1977, with incidents of violence still being reported and a military brigade in Lahore refusing to fire upon a rampaging crowd of rioters, General Zia toppled the regime and imposed Pakistan’s third martial law.

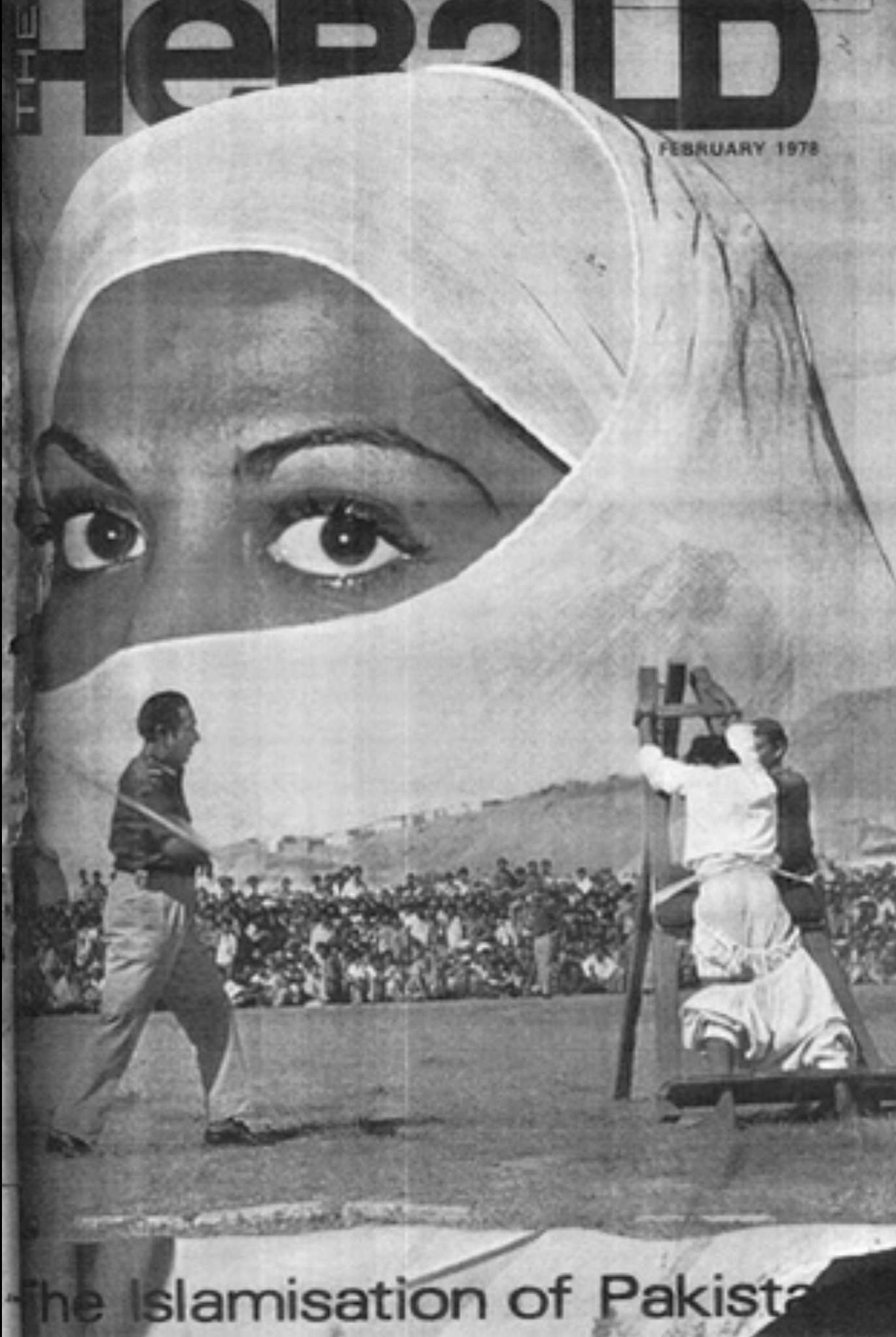

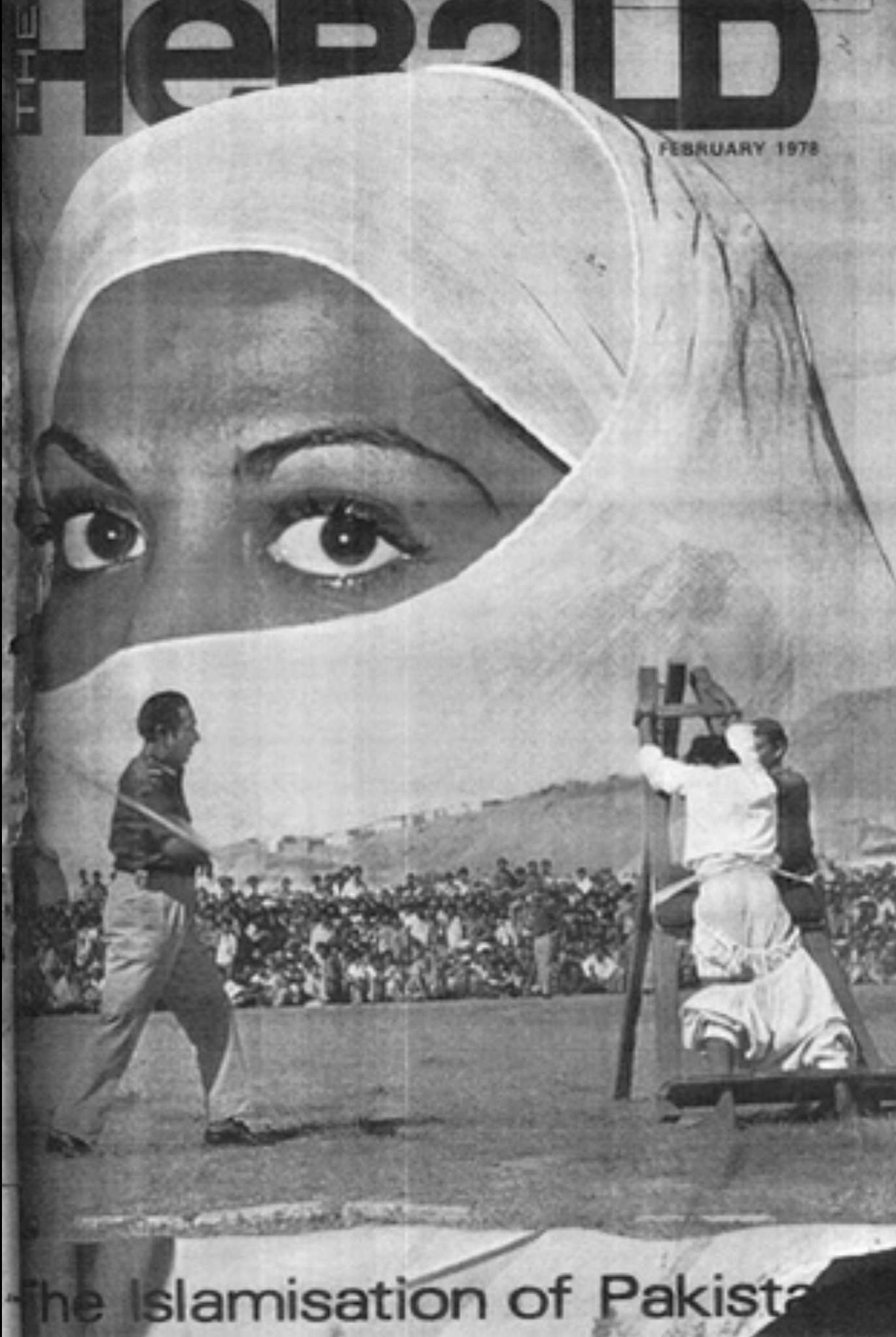

A shrinking economy was unable to accommodate rapid urbanisation, growth in population and demand for jobs. Large sections of the affected population gravitated towards PNA’s promises of building an ‘Islamic society’ and economy on the model prescribed by the first four (‘rightly guided’) caliphs of Islam. PNA’s movement was also supported and funded by industrialists and businesses whose interests had been hurt by the regime’s chaotic socialist policies. Bhutto was arrested, tried for murder and executed through a sham trial in 1979. Zia, as dictator, adopted PNA’s Islamic program.

Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD), 1983

As incidents of agitation and resistance against the Zia dictatorship increased, the PPP formed Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD) in 1981. The alliance included eight parties, mostly left-wing and secular centrist, and one anti-Zia Islamic party, the JUI-F.

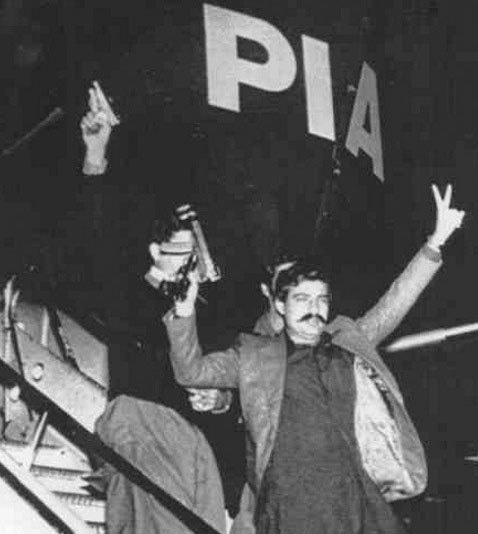

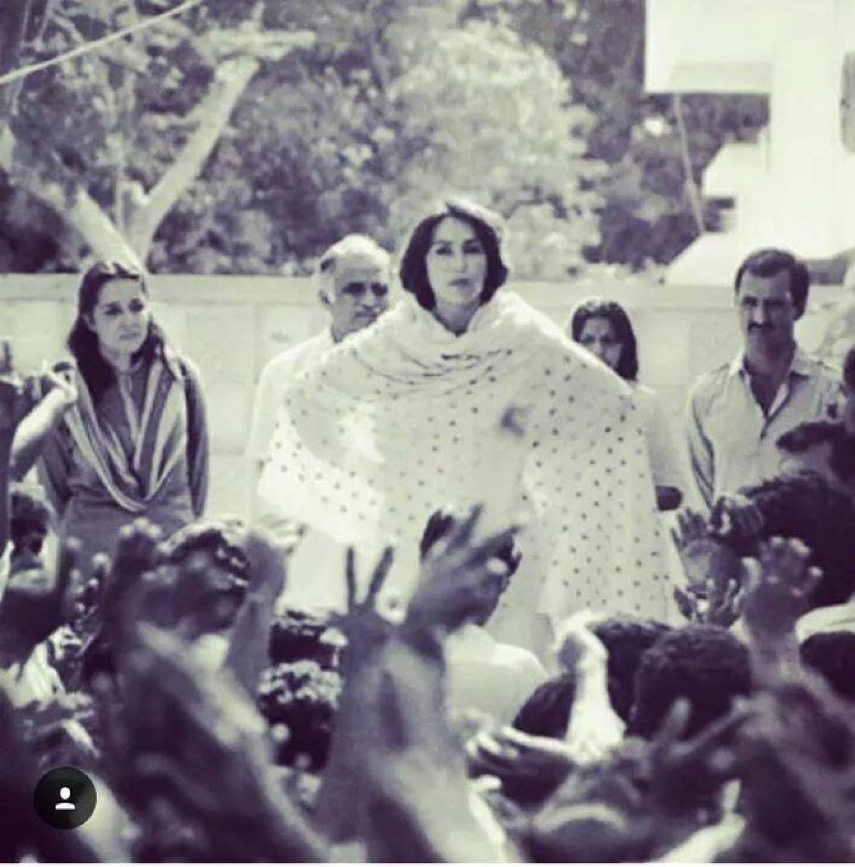

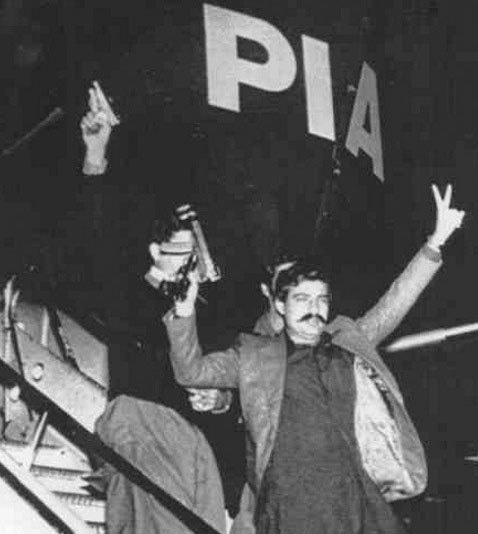

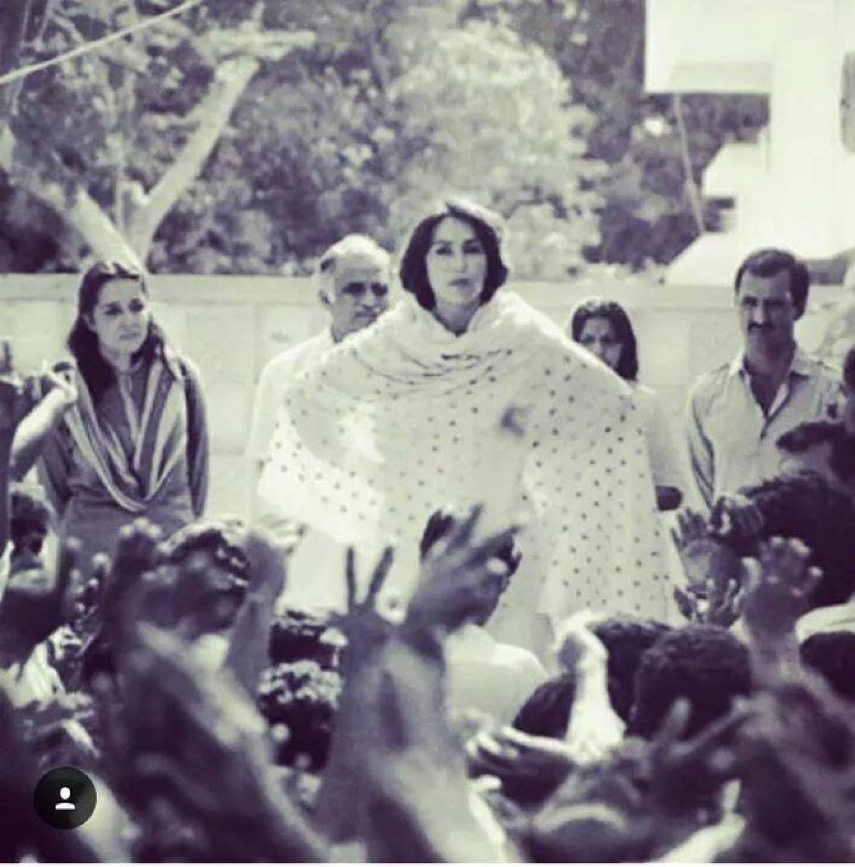

The March 1981 hijacking of a PIA plane stalled the MRD because it was executed by men belonging to Al-Zulfikar — a left-wing urban guerrilla outfit formed by ZA Bhutto’s sons. Their sister, Benazir, who was leading the MRD, was critical of the hijacking because it provided Zia the excuse to further intensify the regime’s oppression against all opposition.

As Zia consolidated his position with the support of the US and Saudi economic and military aid and a number of draconian laws, MRD rebounded in 1983 with a countrywide protest movement.

The movement turned violent, first in PPP strongholds in Karachi ...

... and then across Sindh, where the Zia dictatorship had to bomb certain villages and armoured tanks to control the violence.

Zia survived the onslaught, and in December 1983, MRD called off the agitation after dozens were killed by the military and hundreds arrested and tortured. Another reason for calling off the agitation was the fact that the movement in Sindh had taken the shape of a militant Sindhi nationalist venture.

Zia faced another MRD movement in 1986 before dying in a controversial plane crash in 1988. PPP won the first post-Zia election.

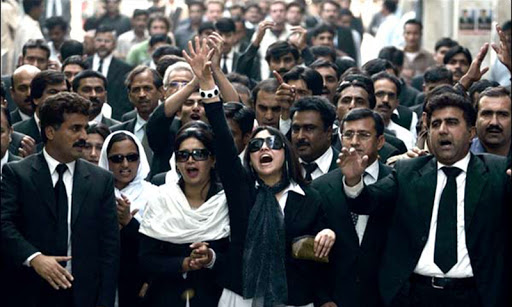

The Lawyers Movement (2007)

In October 1999, General Pervez Musharraf toppled the second PML-N/Nawaz Sharif regime and imposed the country’s fourth martial law.

Like the Ayub coup, Musharraf’s coup was initially popular after a rise of sectarian violence, economic downturns, and a decade of continuous bickering between PML-N, PPP, and the military-establishment

The economy stabilised, ethnic tensions subsided, and many sectarian and Islamist outfits were outlawed.

However, the situation began to unravel from 2006 onwards. With the two main opposition parties, PPP and PML-N, in the dock, opposition from radical right-wing groups got bolder leading to street violence and terrorist attacks. Much of the macro-economic successes of the regime did not trickle down very far. By 2006, increased income inequalities and rising inflation had begun to negatively affect the mood of the polity. The regime further complicated things for itself by going all-out against certain Islamist militant groups but nourishing some to retain Pakistan’s influence in Afghanistan.

Then Musharraf dismissed the Chief Justice of Pakistan (CJP), Iftikhar Chaudhry on corruption charges.

Lawyers came out to protest the dismissal. Apart from demanding the restoration of the CJP, they began to also demand Musharraf’s resignation. The movement gained momentum when PPP and PML-N joined it and their top leaders returned from exile.

The police used brutal tactics to stall the movement, but it kept on growing.

The movement turned deadly when MQM militants attacked pro-CJP rallies organised by PPP and ANP in Karachi to welcome the CJP's arrival in Karachi. Dozens were killed in street fighting in which sophisticated weapons were used. Musharraf was unmoved by the violence and actually hailed the MQM which was supporting his regime.

At the same time, military action against Islamist militants who had hijacked a mosque and madrasah in Islamabad triggered the formation of Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) an alliance of various militant groups who began to target civilians and security forces through suicide bombings and assassinations. In one such attack, Benazir Bhutto, the chairperson of the PPP was killed.

In 2008, the PPP and PML-N won majorities in the election, ousting the pro-Musharraf PML-Q. After facing impeachment, Musharraf resigned.

Pakistan Democratic Alliance, 2020-ongoing.

In September 2020, 11 opposition parties in Pakistan formed the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM). The alliance includes two of the country’s three major parties, the PML-N and the left-liberal PPP. The third major party, the centre-right PTI has been in power since the controversial August 2018 election, heading a coalition government with some smaller parties such as the centrist MQM-P, the right-wing PML-Q, the pro-state Baloch outfit, BAP, and some independents.

The parties in PDM also include the mainstream Islamic party, the JUI-F (Deobandi), a faction of the Sunni Barelvi JUP, progressive Pashtun nationalist outfits, PkMWP, the ANP and the PTM, the left-leaning Baloch parties, the BNP-Mengal and National Party, and the centrist QWP.

The PDM has accused the PTI of coming to power through a blatantly rigged election that was ‘engineered’ by the powerful ‘military-establishment’ which had a severe falling out with the last PML-N regime on issues of foreign policy, and the handling of terrorist groups which PML-N accused the military-establishment of ignoring in its otherwise unprecedented operation against hardcore Islamist insurgent outfits. The military largely won the war against these groups, but the PML-N government, then being headed by PM Nawaz Sharif, was of the view that some sectarian and militant ‘assets’ were being protected. The claim worsened the already widening rift between PML-N and the military.

PML-N and the PPP have had a history of tensions with the establishment. But even though both parties have continued to make comebacks despite attempts by various politically invested organs of the state poised against them, this time they (especially PML-N) have pledged to work (through the PDM) to not only dislodge the PTI regime through a protest movement but also push back the political role of the military.

After a decade of political chaos, military chief Ayub Khan imposed the country’s first martial law in 1958. It was initially a popular coup which Ayub explained as a ‘revolution.’

With his regime’s economic policies and industrialisation project bearing fruit, Ayub remained firmly in the saddle till 1965. The opposition was weak and scattered.

After the war ended in a stalemate, fissures began to appear within the regime. The war negatively impacted the economy as well. The trickle-down effect that his economic policies were expected to create instead bolstered the fortunes of a handful of business groups. The gap between the rich and the poor widened, creating resentment.

In 1968, the resentment came to the surface. A protest movement, mainly by left-wing student groups, turned violent and was soon joined by opposition parties, trade unions and eventually by small farmers and peasants.

It was a nationwide movement that triggered riots and strikes in both wings of the country, West Pakistan and East Pakistan. Leftist parties such as PPP and NAP demanded parliamentary democracy and a socialist economy, whereas in East Pakistan, the Bengali nationalist Awami League demanded provincial autonomy. Dozens were killed. Ayub’s political system was not inclusive, leaving large sections of the society feeling alienated.

Unable to stall the violence, Ayub resigned in March 1969. He handed over power to General Yahya Khan who imposed the country’s second martial law. He restored the provinces (abolished in 1955) and oversaw Pakistan’s first parliamentary elections held on adult franchise. Yahya resigned in December 1971 after Pakistan lost its eastern wing in a civil war. Power was transferred to civilian representatives after 13 years.

The PNA Movement, 1977

ZA Bhutto’s left-liberal PPP had swept the 1970 elections in West Pakistan’s two most populous provinces, Punjab and Sindh. After the departure of East Pakistan and Yahya, Bhutto became president and his government at once initiated economic reforms based on his party’s idea of socialism. Reforms were also introduced in the bureaucracy and the military.

After navigating his way through the economic and political fall-outs of the disastrous 1971 civil war and the loss of East Pakistan, Bhutto oversaw the passing of a new constitution in 1973 which turned Pakistan into a parliamentary democracy. Bhutto became prime minister. He neutralised a violent movement against the Ahmadiyya community by Islamic parties by agreeing to constitutionally oust the community from the fold of Islam.

By 1975, despite a Baloch nationalist insurgency, ZA Bhutto had largely overcome the many problems that his regime had faced in its first few years. But economy became a concern when the regime’s ‘socialist’ policies began to badly impact businesses and industry. This problem was compounded by an international oil crises which pushed up oil prices to unprecedented levels. By 1976, Bhutto was confident enough to call fresh elections in 1977, a year ahead of schedule. The opposition often described the Bhutto regime as ‘civilian dictatorship’ that used the police and the PM’s special security force, the FSF, to browbeat opposition outside and within his own party into submission.

The PPP swept the election against PNA — an alliance of right-wing Islamic and centre-right parties demanding Islamic laws, deregulation of the economy and rollback of economic and land reforms. PNA cried foul, accusing the regime of rigging the polls and of political harassment.

PNA called for countrywide protests that quickly turned violent, especially in Karachi and Lahore. Dozens were killed.

The violence intensified, as protesters set fire to homes of some PPP leaders, police stations, public buses, liquor stores, bars, cinemas and banks.

Bhutto was forced to negotiate with PNA leaders and agreed to accept many of their demands. But in July 1977, with incidents of violence still being reported and a military brigade in Lahore refusing to fire upon a rampaging crowd of rioters, General Zia toppled the regime and imposed Pakistan’s third martial law.

A shrinking economy was unable to accommodate rapid urbanisation, growth in population and demand for jobs. Large sections of the affected population gravitated towards PNA’s promises of building an ‘Islamic society’ and economy on the model prescribed by the first four (‘rightly guided’) caliphs of Islam. PNA’s movement was also supported and funded by industrialists and businesses whose interests had been hurt by the regime’s chaotic socialist policies. Bhutto was arrested, tried for murder and executed through a sham trial in 1979. Zia, as dictator, adopted PNA’s Islamic program.

Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD), 1983

As incidents of agitation and resistance against the Zia dictatorship increased, the PPP formed Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD) in 1981. The alliance included eight parties, mostly left-wing and secular centrist, and one anti-Zia Islamic party, the JUI-F.

The March 1981 hijacking of a PIA plane stalled the MRD because it was executed by men belonging to Al-Zulfikar — a left-wing urban guerrilla outfit formed by ZA Bhutto’s sons. Their sister, Benazir, who was leading the MRD, was critical of the hijacking because it provided Zia the excuse to further intensify the regime’s oppression against all opposition.

As Zia consolidated his position with the support of the US and Saudi economic and military aid and a number of draconian laws, MRD rebounded in 1983 with a countrywide protest movement.

The movement turned violent, first in PPP strongholds in Karachi ...

... and then across Sindh, where the Zia dictatorship had to bomb certain villages and armoured tanks to control the violence.

Zia survived the onslaught, and in December 1983, MRD called off the agitation after dozens were killed by the military and hundreds arrested and tortured. Another reason for calling off the agitation was the fact that the movement in Sindh had taken the shape of a militant Sindhi nationalist venture.

Zia faced another MRD movement in 1986 before dying in a controversial plane crash in 1988. PPP won the first post-Zia election.

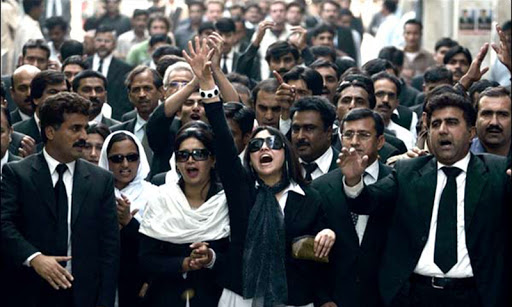

The Lawyers Movement (2007)

In October 1999, General Pervez Musharraf toppled the second PML-N/Nawaz Sharif regime and imposed the country’s fourth martial law.

Like the Ayub coup, Musharraf’s coup was initially popular after a rise of sectarian violence, economic downturns, and a decade of continuous bickering between PML-N, PPP, and the military-establishment

The economy stabilised, ethnic tensions subsided, and many sectarian and Islamist outfits were outlawed.

However, the situation began to unravel from 2006 onwards. With the two main opposition parties, PPP and PML-N, in the dock, opposition from radical right-wing groups got bolder leading to street violence and terrorist attacks. Much of the macro-economic successes of the regime did not trickle down very far. By 2006, increased income inequalities and rising inflation had begun to negatively affect the mood of the polity. The regime further complicated things for itself by going all-out against certain Islamist militant groups but nourishing some to retain Pakistan’s influence in Afghanistan.

Then Musharraf dismissed the Chief Justice of Pakistan (CJP), Iftikhar Chaudhry on corruption charges.

Lawyers came out to protest the dismissal. Apart from demanding the restoration of the CJP, they began to also demand Musharraf’s resignation. The movement gained momentum when PPP and PML-N joined it and their top leaders returned from exile.

The police used brutal tactics to stall the movement, but it kept on growing.

The movement turned deadly when MQM militants attacked pro-CJP rallies organised by PPP and ANP in Karachi to welcome the CJP's arrival in Karachi. Dozens were killed in street fighting in which sophisticated weapons were used. Musharraf was unmoved by the violence and actually hailed the MQM which was supporting his regime.

At the same time, military action against Islamist militants who had hijacked a mosque and madrasah in Islamabad triggered the formation of Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) an alliance of various militant groups who began to target civilians and security forces through suicide bombings and assassinations. In one such attack, Benazir Bhutto, the chairperson of the PPP was killed.

In 2008, the PPP and PML-N won majorities in the election, ousting the pro-Musharraf PML-Q. After facing impeachment, Musharraf resigned.

Pakistan Democratic Alliance, 2020-ongoing.

In September 2020, 11 opposition parties in Pakistan formed the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM). The alliance includes two of the country’s three major parties, the PML-N and the left-liberal PPP. The third major party, the centre-right PTI has been in power since the controversial August 2018 election, heading a coalition government with some smaller parties such as the centrist MQM-P, the right-wing PML-Q, the pro-state Baloch outfit, BAP, and some independents.

The parties in PDM also include the mainstream Islamic party, the JUI-F (Deobandi), a faction of the Sunni Barelvi JUP, progressive Pashtun nationalist outfits, PkMWP, the ANP and the PTM, the left-leaning Baloch parties, the BNP-Mengal and National Party, and the centrist QWP.

The PDM has accused the PTI of coming to power through a blatantly rigged election that was ‘engineered’ by the powerful ‘military-establishment’ which had a severe falling out with the last PML-N regime on issues of foreign policy, and the handling of terrorist groups which PML-N accused the military-establishment of ignoring in its otherwise unprecedented operation against hardcore Islamist insurgent outfits. The military largely won the war against these groups, but the PML-N government, then being headed by PM Nawaz Sharif, was of the view that some sectarian and militant ‘assets’ were being protected. The claim worsened the already widening rift between PML-N and the military.

PML-N and the PPP have had a history of tensions with the establishment. But even though both parties have continued to make comebacks despite attempts by various politically invested organs of the state poised against them, this time they (especially PML-N) have pledged to work (through the PDM) to not only dislodge the PTI regime through a protest movement but also push back the political role of the military.