British colonialism in the Indian subcontinent has long been a fierce topic of debate. Indians, Pakistanis, Bangladeshis and the British all have their own deeply held personal thoughts about the long-lasting impact that the British Raj had on South Asia. To say the least, the British occupation of India has a long, complex and twisted history, creating a rather unique historical debate. However, it seems that conversation around this topic has become a bit too black and white.

While it is impossible to describe in this article the horrific and long-lasting impacts colonialism has had on South Asia, numerous personal perspectives are often missing from the ongoing conversations. Discussions on the topic will mention the overarching and general impacts of the region, but will fail to include crucial individuals involved in the colonial history. As a scholar and student of South Asian studies, I believe that these more personal, intimate views should be included in the conversations around the legacy of the British Raj. As without them, a crucial portion of history is missing.

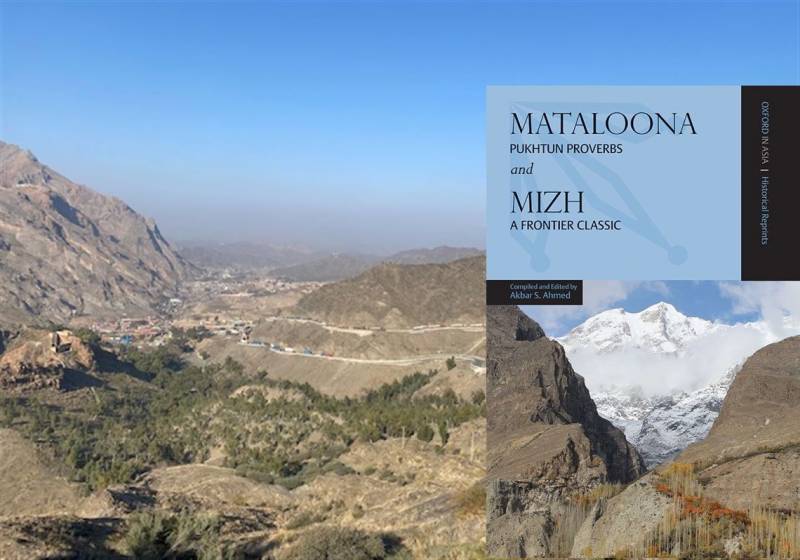

As historians and anthropologists continue to investigate the colonial era, new information will come to light to add to the depth of conversations around the British Raj. A newly released book by Pakistani anthropologist and ambassador Akbar Ahmed does exactly that.

Dr. Ahmed’s new book Mataloon and Mizh dives deep into personal interactions that he had while serving in the subcontinent. Dr. Ahmed writes on two legendary British political officers who served in the North-West Frontier Province:

. In the book, which surfaces previously secret confidential official material, the officers offer an alternative view of British-Indian relations.

Both Sir Olaf Canoe and Sir Evelyn Howell have expressed deep personal admiration for the local Pukhtun people. When discussing his time in Waziristan with Caroe, Howell declared at the end of his life that: “he [Howell] would feel happier in the mountain ranges of Waziristan. It was he, he said, precisely because that was the most dangerous period of his life that it had become the period that he loved most. Often in his dreams he found himself in Waziristan, and his heart flying in those precipitous gorges.” In addition to this, Howell said to other British officers that he was greatly impressed by the “fine type of man that Pukhtun society produces” after lengthy conversations with Pukhtun elders.

Sir Olaf Caroe, the former governor of the Pakistani North-West Frontier Province, expressed very similar sentiments: “…as he [Caroe] drove through the Margalla pass just north of Rawalpindi and went on to cross the great bridge of Attock, there was a lifting of the heart and the knowledge that…he had come home.” In fact, it was Caroe’s love for the Pukhtun people and the Frontier Province that likely costed him his job as Governor of the Province, as the Indian Congress accused Caroe of being too close to the Muslim League, and Congress worked to replace him.

These examples show us that even at the height of the British empire, leading officials exhibited deep respect and curiosity for the people and land that they were ruling over. Even though turbulent times, these men still showed interest in learning the language and culture of the people of South Asia. Decades later after they had left India, they continued to show their respect for the people they had ruled over. Caroe and Howell exhibited great humanity in their respect for the Indian and Pakistani people in their books and articles. Caroe’s The Pathans and Howell’s Mizh remain classics. In fact, they have contributed in creating a rather romantic view of the Pukhtun peoples.

As a student of South Asia, these quotes add an incredibly interesting perspective on the history. These officers clearly had a great humanitarian respect for the people of South Asia, even if the policies that they were caring out did not reflect that. As an American, I have heard similar stories from soldiers who served in Iraq or Afghanistan. While they were a part of an invasive military industrial complex, many of them came back with a great respect for the area that they were serving in. The element of human empathy should not be overlooked.

While these historical factoids do not alter the damage inflicted onto India and its people, it does represent a more holistic representation of the legacy of colonialism. While Caroe and Howell were a part of an evil imperialist system, they sought to perform good from the inside of the global British system. It is clear from these comments that the officers had a richer understanding of this civilization than most have recognized historically.

I find it troubling that many historians are now taking rather polarizing views on history and the legacy of British colonialism. The most prominent historian of such is Indian member of Parliament Shashi Tharoor, who has passionately taken up this issue. In his his viral Oxford Union lecture, Tharoor attempted to calculate the damages to India’s economy and people by British imperialism. However, in his lecture, Tharoor takes a rather uncompromising perspective on the British occupation.

Tharoor seems to paint a black and white painting of the British officers and their relationships with the people and land of South Asia. In his delivery, he implies that he does not allow for nuance or deviating perspectives on this topic. I am afraid that to some aspect, Tharoor is throwing the baby out with the bathwater when it comes to this discussion.

However, I would like to note that Tharoor is one of the great scholars of Indian history and I am not challenging his argument. His passion for British reparations to India is not an argument that should not be brushed aside, but rather embraced by Indians and Pakistanis for international recognition of the horrors of the British Raj.

It seems that there is a grave dehumanizing process that has taken place. Everything is reduced to “us versus them”. In this process, figures like Howell and Caroe are forgotten.

With this new information, it offers us something rather unique that is worthy of exploring. This aspect of colonialism is what is all too often lost in the pages of the history books. The human element side is an area worth exploration, as the voices of the British, Indians and Pakistanis should be heard.

The newly surfaced material should add to the discussions around colonialism, and should not be simply ignored, even as it deviates from the current narrative. As with any historical topic, we have the responsibility as scholars to continue and evolve our conversations as new information comes to light. With this history, let’s continue that discussion.

While it is impossible to describe in this article the horrific and long-lasting impacts colonialism has had on South Asia, numerous personal perspectives are often missing from the ongoing conversations. Discussions on the topic will mention the overarching and general impacts of the region, but will fail to include crucial individuals involved in the colonial history. As a scholar and student of South Asian studies, I believe that these more personal, intimate views should be included in the conversations around the legacy of the British Raj. As without them, a crucial portion of history is missing.

As historians and anthropologists continue to investigate the colonial era, new information will come to light to add to the depth of conversations around the British Raj. A newly released book by Pakistani anthropologist and ambassador Akbar Ahmed does exactly that.

Dr. Ahmed’s new book Mataloon and Mizh dives deep into personal interactions that he had while serving in the subcontinent. Dr. Ahmed writes on two legendary British political officers who served in the North-West Frontier Province:

. In the book, which surfaces previously secret confidential official material, the officers offer an alternative view of British-Indian relations.

Both Sir Olaf Canoe and Sir Evelyn Howell have expressed deep personal admiration for the local Pukhtun people. When discussing his time in Waziristan with Caroe, Howell declared at the end of his life that: “he [Howell] would feel happier in the mountain ranges of Waziristan. It was he, he said, precisely because that was the most dangerous period of his life that it had become the period that he loved most. Often in his dreams he found himself in Waziristan, and his heart flying in those precipitous gorges.” In addition to this, Howell said to other British officers that he was greatly impressed by the “fine type of man that Pukhtun society produces” after lengthy conversations with Pukhtun elders.

Sir Olaf Caroe, the former governor of the Pakistani North-West Frontier Province, expressed very similar sentiments: “…as he [Caroe] drove through the Margalla pass just north of Rawalpindi and went on to cross the great bridge of Attock, there was a lifting of the heart and the knowledge that…he had come home.” In fact, it was Caroe’s love for the Pukhtun people and the Frontier Province that likely costed him his job as Governor of the Province, as the Indian Congress accused Caroe of being too close to the Muslim League, and Congress worked to replace him.

These examples show us that even at the height of the British empire, leading officials exhibited deep respect and curiosity for the people and land that they were ruling over. Even though turbulent times, these men still showed interest in learning the language and culture of the people of South Asia. Decades later after they had left India, they continued to show their respect for the people they had ruled over. Caroe and Howell exhibited great humanity in their respect for the Indian and Pakistani people in their books and articles. Caroe’s The Pathans and Howell’s Mizh remain classics. In fact, they have contributed in creating a rather romantic view of the Pukhtun peoples.

As a student of South Asia, these quotes add an incredibly interesting perspective on the history. These officers clearly had a great humanitarian respect for the people of South Asia, even if the policies that they were caring out did not reflect that. As an American, I have heard similar stories from soldiers who served in Iraq or Afghanistan. While they were a part of an invasive military industrial complex, many of them came back with a great respect for the area that they were serving in. The element of human empathy should not be overlooked.

While these historical factoids do not alter the damage inflicted onto India and its people, it does represent a more holistic representation of the legacy of colonialism. While Caroe and Howell were a part of an evil imperialist system, they sought to perform good from the inside of the global British system. It is clear from these comments that the officers had a richer understanding of this civilization than most have recognized historically.

I find it troubling that many historians are now taking rather polarizing views on history and the legacy of British colonialism. The most prominent historian of such is Indian member of Parliament Shashi Tharoor, who has passionately taken up this issue. In his his viral Oxford Union lecture, Tharoor attempted to calculate the damages to India’s economy and people by British imperialism. However, in his lecture, Tharoor takes a rather uncompromising perspective on the British occupation.

Tharoor seems to paint a black and white painting of the British officers and their relationships with the people and land of South Asia. In his delivery, he implies that he does not allow for nuance or deviating perspectives on this topic. I am afraid that to some aspect, Tharoor is throwing the baby out with the bathwater when it comes to this discussion.

However, I would like to note that Tharoor is one of the great scholars of Indian history and I am not challenging his argument. His passion for British reparations to India is not an argument that should not be brushed aside, but rather embraced by Indians and Pakistanis for international recognition of the horrors of the British Raj.

It seems that there is a grave dehumanizing process that has taken place. Everything is reduced to “us versus them”. In this process, figures like Howell and Caroe are forgotten.

With this new information, it offers us something rather unique that is worthy of exploring. This aspect of colonialism is what is all too often lost in the pages of the history books. The human element side is an area worth exploration, as the voices of the British, Indians and Pakistanis should be heard.

The newly surfaced material should add to the discussions around colonialism, and should not be simply ignored, even as it deviates from the current narrative. As with any historical topic, we have the responsibility as scholars to continue and evolve our conversations as new information comes to light. With this history, let’s continue that discussion.