Much has been written about the four successful military coups in Pakistan (1958; 1969; 1977 and 1999). But there were at least five more attempts that failed. Nadeem F Paracha recalls those.

The 20th century was an era of military coups mostly in developing countries in Asia, Africa, and South America. The phenomenon was largely associated with the dynamics of the erstwhile Cold War — a conflict fought through proxies distributed in two ‘camps,’ the United States and the Soviet Union.

Military coups were prominent tools used by the two superpowers to initiate rapid regime changes in countries where a government was perceived to have become a threat to the regional, political and economic interests of the major powers.

Ideology too played a role, but it was only tributary compared to interests which were related more to the realpolitik of the Cold War.

Both the US and Soviet Union used their intelligence agencies to infiltrate the political and military circles of various countries. They helped plan and bankroll military coups and the regimes which came to power through these coups. The US was more successful in this respect. It backed and funded a number of military coups across Asia, Africa and South America. It then sustained military dictatorships because they were seen as barriers against communists who largely tilted towards the ‘Soviet camp.’

After the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, military dictatorships began to be replaced by democratic set-ups. Military coups became extremely rare as well.

Between 1900 and 1999, well over 300 military coups and attempted coups took place across the world. During the first four decades of the 20th century, European regions witnessed the most number of coups. During the last 5 decades of the same century, a majority of coups took place in Africa, Asia, and South America.

From 2000 to 2020, there have been less than 50 coups and coup attempts.

Fallen Horses: Pakistan

Much has been written about the four successful military coups in Pakistan (1958; 1969; 1977 and 1999). But there were at least five more attempts that failed.

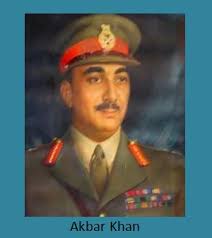

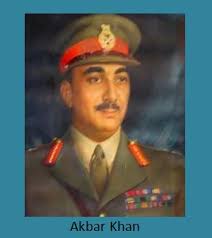

Details about the failed attempts have only come out slowly. The first such attempt was made in 1951 (against the regime of Liaquat Ali Khan). The attempt was led by Major-General Akbar Khan. Akbar Khan had been a hero in Pakistan’s first war against India over the Kashmir issue in 1948. The war had ended in a stalemate after the United Nations (UN) intervened. Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan accepted the UN’s peace plan.

Akbar Khan was furious. He was an admirer of Turkey’s nationalist leader Kamal Ataturk (d. 1938). In 1950, when the outgoing military chief of Pakistan, General Douglas Gracey (a Briton) was handing over the reins of the military to its new chief, Ayub Khan, he told him that Akbar was part of a group of ‘Kamalests’ in the army and should be watched.

Akbar Khan’s wife was close to the country’s left-wing intelligentsia. She was also on good terms with the Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP). When Akbar Khan began to talk about a nationalist coup against the Liaquat regime with some sympathetic officers, his wife suggested that the CPP be brought on board as well.[1]

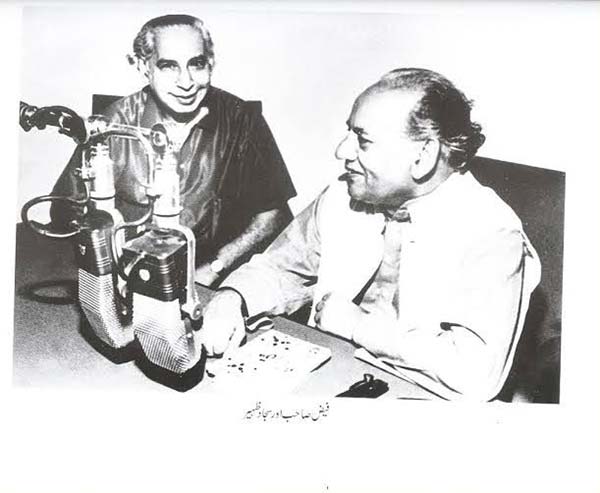

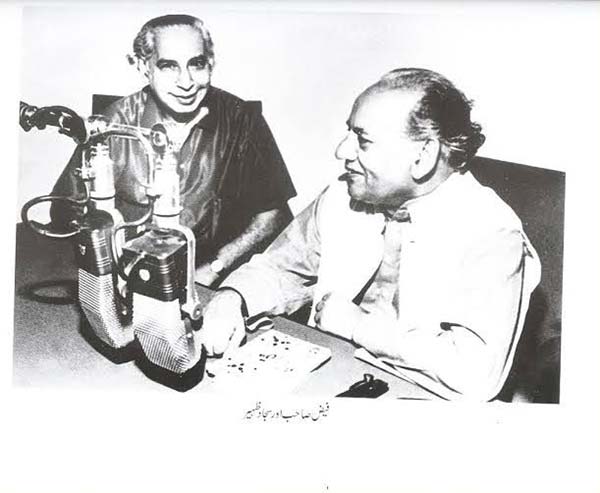

It was through her that Akbar contacted some leading CPP members, which included author and Marxist ideologue, Sajjad Zaheer, and famous Urdu poet and journalist, Faiz Ahmed Faiz. Even though Akbar had insisted that his coup would be ‘nationalistic’ in essence, he asked the CPP to help him mobilise the masses (through the party’s student and labour unions). He also agreed to carry out socialist reforms (after the coup).

Twelve military officers, three members of the CPP, and Akbar’s wife become the core group which was to navigate the coup. The plan was to take over strategic state and government buildings and the radio stations with the help of rebel battalions and regiments, and the military chief was to be arrested along with the PM. Power was to be handed over to a ‘revolutionary military junta.’

But the coup plan collapsed when one of Akbar Khan’s confidants, a police officer, leaked the plan to the government. Eleven military officers and four civilians were arrested, including Akbar’s wife. The wife was, however, released, but Akbar, along with all other plotters were given long jail sentences. Sajjad Zaheer was sent back to India from where he had arrived in 1948 to organise the CPP.

All the arrested men were released six years later in 1957. Zafarullah Poshni, who was an army captain at the time and was also arrested, wrote that the plan was always doomed to failure. Akbar was a boastful character and so was his wife. Those who were arrested claimed that Ayub and Liaquat were forced by the US to use the episode to nip communism in Pakistan in the bud.

The second such attempt which was foiled was made in 1973 against the government of ZA Bhutto. Bhutto’s left-leaning and populist Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) had come to power in December 1971 after East Pakistan separated and became an independent country. The PPP had swept the 1970 elections in West Pakistan.

The coup plan was hatched by a group of officers who had actually paved the way for Bhutto to come to power. After a vicious civil war between the Pakistan army and militant Bengali nationalists saw East Pakistan become Bangladesh, these officers had forced the end of the Yahya Khan dictatorship.

They asked General Yahya to resign and hand over power to Bhutto, unless he wanted to be removed through an officer’s coup. Yahya resigned. However, weary of ‘activist officers,’ the Bhutto regime began to systematically remove them. Bhutto described them as ‘Bonapartists.’[2]

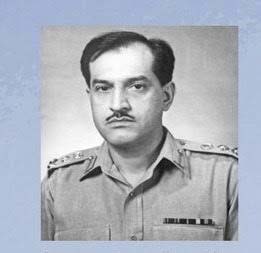

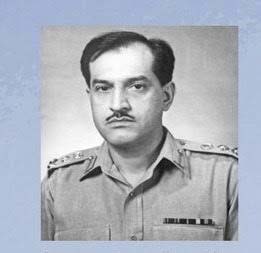

Enraged by the ploy, and believing that officers who had been weak and corrupt during the East Pakistan war were being retained, the rebel group began to plot a coup d’etat against Bhutto with the help of sympathetic officers and soldiers. One of the leading plotters was Brigadier FB. Ali. He had originally been a Bhutto supporter, and was one of the officers who had forced Yahya to resign.

He turned against the Bhutto regime after it began to dismiss many of his colleagues. In 1972, the regime dismissed Ali as well. Noticing that the regime’s actions had created resentment among many officers, Brig. Ali, along with Major Farouk Adam Khan, Squadron Leader Ghous, Colonel Aleem Afridi and Lt. Colonel Tariq Rafi began plotting a coup to oust Bhutto.[3]

It is not known what sort of a government they were planning to install as a replacement, but evidence has surfaced that they were looking to set up a military junta populated by officers who would also see the removal of the generals elevated by Bhutto. According to their lawyer, SM Zaffar, these officers believed that East Pakistan was lost because the military and governments of Pakistan were not Islamic.

Colonel Afridi quietly backed out from the plan and then informed the military’s top leadership about it. The conspirators were arrested, court martialed and jailed. The alleged conspirators were handed the death sentence that was then commutated to life imprisonment. The accused were eventually released in 1978. Ironically, the court martial proceedings were conducted by a Lieutenant General called Ziaul Haq. Four years later, he was made the army chief by Bhutto. In July 1977, he toppled Bhutto in a coup. It was during his dictatorship that the sentenced men were released.

The next failed coup attempt came in 1980. This was against the Ziaul Haq dictatorship which itself was established through a reactionary military coup in July 1977. This attempt was led by Tajammul Hussain Malik, a two-star general in the Pakistan army. One of the few heroes to emerge from the 1971 East Pakistan debacle, Malik was forcibly retired in 1976 by General Ziaul Haq for being a threat to the regime of ZA Bhutto. During his dismissal of Malik, Zia told him he was a ‘fanatic’ and could not be trusted.[5]

Outraged by his ‘forced retirement,’ he planned to oust the Bhutto regime. The plan was aborted when Malik could not gather enough support from serving officers.[6]

A few months later, General Zia toppled Bhutto and declared martial law. Malik, however, returned to the scene in 1980, this time to plot a coup against the Zia regime. He managed to bag the backing of some senior officers, including his son, and planned to assassinate Zia during Pakistan’s Republic Day parade on March 23, 1980.

The plan was to eliminate Zia and install a radical ‘Islamic’ military junta which would replace Zia’s ‘fake Islamic regime’ with ‘a genuine one.’[6] It is not known what a ‘genuine Islamic regime’ meant to the plotters. But in a 2001 interview he described it as a regime run on the principles of the ‘Khulafa-e-Rashdeen.’ The plot was leaked shortly before going into implementation, and the plotters were all arrested. They were given stern jail sentences, including life imprisonment. They were released in 1988 after the demise of Ziaul Haq and the election of Benazir Bhutto as prime minister.

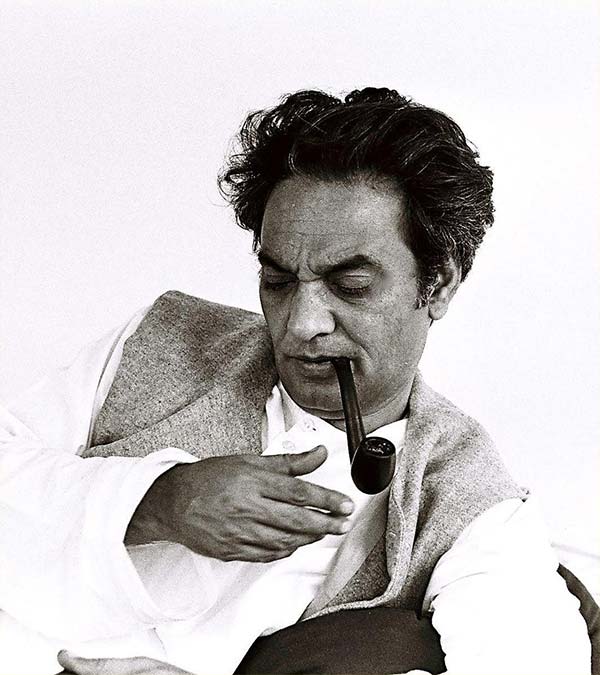

Four years later, in 1984, Zia faced another coup attempt. This time it came from the left. The plot had its roots in 1982 in Lahore when two majors in the Pakistan army met with lawyer, philosopher and Marxist ideologue, Raza Kazim at his residence. Kazim had been in jail a year before for authoring a pamphlet against Ziaul Haq. The majors began expressing their disgruntlement towards the Zia regime, but did not inform him that they were planning to organise a coup against him.

The majors, along with a member of the Pakistan progressive intelligentsia, Ali Mehmood, continued to secretly meet Raza. He was also contacted by Mustafa Khar, a former minister in the ZA Bhutto regime and a senior member of Bhutto’s party. He had flown into exile to the UK after Zia’s 1977 coup. Khar informed Kazim that the majors could be trusted and requested him to help them bring down Zia. Kazim was asked (by the majors) to talk to some other anti-Zia officers about history, philosophy and politics.

In late 1982, Khar and one of the majors, Major Aftab, told Kazim that they were collecting funds to organise exiled Pakistani activists in the UK. They told him that the money would also be used to whip up protests against the Zia dictatorship in Pakistan.

Kazim was a successful lawyer, and he agreed to hand them Rs. 20,000. In total, he gave the plotters over Rs. 90,000. This is when he was eventually told that all this was being done to plan a coup d’etat against the Zia regime.[8]

Decades later, Kazim told the Pakistan monthly magazine, Herald, that the plotters were planning to topple Zia and establish a populist military regime (headed by Major Aftab). Khar had suggested to the plotters that Kazim be given an important post in the new regime and be made its main ideologue.

But the plotters suddenly discontinued their interaction with Kazim. He was already having second thoughts about the whole plan because he thought Major Aftab was a megalomaniac who saw himself as being some kind of a messiah. It was only a year later, in 1984, that Kazim realised that the coup had been planned but was nipped in the bud by military spooks. All the conspirators were arrested, including Kazim. Khar was still in the UK.

They were all given stiff jail sentences, but were released in 1988 by the first Benazir Bhutto regime. It is not known exactly how the plotters had planned to pull off the coup and how many officers were involved. But according to Kazim, over 500 military officers and soldiers were interrogated.[9]

The next failed coup attempt emerged in 1995 against the second Benazir Bhutto regime. It included a group of officers who were close to the Zia regime which had folded in 1988 after his demise. Zia’s appointees in the military had been suspicious of Benazir even when her party had won the first post-Zia election in 1988. They feared that her regime would rollback Pakistan’s nuclear program and Zia’s ‘Islamisation’ policies.

Fears of this nature grew when she returned as PM in 1993. In 1995, Brig. Zaheer Abbasi, Brigadier Mustansir Billa and the Islamic militant Qari Saifullah were arrested by the military high command and accused of planning to overthrow the Benazir government through a coup d’detat.[10] The officers were allegedly planning to launch a coup against what they believed was a ‘liberal and corrupt regime’ hell bent on rolling back Pakistan’s nuclear program and neutralising Zia’s Islamisation project.

After the coup, they planned to impose a strict Islamic set-up and dismiss the then military chief, General Abdul Waheed Kakar. It was actually Gen. Kakar who first discovered the plot through military intelligence. He got the plotters arrested and informed PM Bhutto. The military spooks told Karkar that the mentioned officers were planning to launch a military coup against him and Benazir in collusion with a militant religious outfit that was being funded by the renegade Saudi millionaire, Osama Bin Laden. They had planned to assassinate her and dismiss the army chief.

In 2012, the Pakistan military announced that it had arrested Brigadier Ali Khan and four other officers for having links with the banned Pan-Islamist outfit, Hizbut Tahrir (HuT).[11] A military court convicted Brigadier Ali Khan, Major Sohail Akbar, Major Jawad Baseer, Major Inayat Aziz and Major Iftikhar for having links with HuT and sentenced them to rigorous imprisonment for terms ranging from 5 years to 18 months. Even though the military didn’t make any mention of a coup attempt, many believe that the officers were planing an ‘Islamic coup’ against the Zardari regime and the military high command which, at the time, was being headed by General Ashfaq Pervez Kayani.

According to a detailed report in Dawn, back in 2003, HuT established links with about 13 commandos of the army’s Special Services Group (SSG). Then in 2009 officers up to the ranks of lieutenant colonel faced court martial for links with HuT and in 2011 a brigadier faced the same charges. In two of these incidents the same HuT members approached the army officers in 2009 and 2011. According to military intelligence documents quoted by Dawn, HuT activists Abdul Qadir and Ahmed, a doctor, were found to have links with Lt-Col Shahid Bashir in 2009 and Brig Ali Khan in 2011.

The documents revealed that both activists of the banned outfit had used the same techniques for establishing links with Lt-Col Bashir and Brig Ali Khan as they developed relations with the officers through common friends and then used the two officers to approach other army officers. The plan was to initiate a mutiny in the military that would lead to an officers coup and put Pakistan at the centre of an emerging international caliphate.

[1] Z. Poshni: Prison Interlude - The Last Eyewitness Account of the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case (Oxford University Press, 2019).

[2] R. Jetly: Pakistan in Regional and Global Politics (Routledge, 2012)

[3] V. Nasr: The Vanguard of the Islamic Revolution (University of California Press, 1994).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Tajammul Hussain Malik by Agha Amin (PAKPOTPOURRI, 2001).

[6] TH Malik: The Story Of My Struggle (Jang Publishers, 1991).

[7] Raza Kazim interview with S. Ijaz (Herald, September, 2014)

[8] S. Ijaz. op. cit.

[9] Ibid.

[10] L. Ziring: Pakistan at the Cross Currents of History (Oxford University Press, 2004)

[11] Dawn, 29 Oct. 2012.

The 20th century was an era of military coups mostly in developing countries in Asia, Africa, and South America. The phenomenon was largely associated with the dynamics of the erstwhile Cold War — a conflict fought through proxies distributed in two ‘camps,’ the United States and the Soviet Union.

Military coups were prominent tools used by the two superpowers to initiate rapid regime changes in countries where a government was perceived to have become a threat to the regional, political and economic interests of the major powers.

Ideology too played a role, but it was only tributary compared to interests which were related more to the realpolitik of the Cold War.

Both the US and Soviet Union used their intelligence agencies to infiltrate the political and military circles of various countries. They helped plan and bankroll military coups and the regimes which came to power through these coups. The US was more successful in this respect. It backed and funded a number of military coups across Asia, Africa and South America. It then sustained military dictatorships because they were seen as barriers against communists who largely tilted towards the ‘Soviet camp.’

After the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, military dictatorships began to be replaced by democratic set-ups. Military coups became extremely rare as well.

Between 1900 and 1999, well over 300 military coups and attempted coups took place across the world. During the first four decades of the 20th century, European regions witnessed the most number of coups. During the last 5 decades of the same century, a majority of coups took place in Africa, Asia, and South America.

From 2000 to 2020, there have been less than 50 coups and coup attempts.

The 1953 US-backed military coup in Iran.

The 1973 US-backed military coup in Chile.

The 1978 Soviet-backed coup in Afghanistan.

The 2013 coup d'état in Egypt.

Fallen Horses: Pakistan

Much has been written about the four successful military coups in Pakistan (1958; 1969; 1977 and 1999). But there were at least five more attempts that failed.

Details about the failed attempts have only come out slowly. The first such attempt was made in 1951 (against the regime of Liaquat Ali Khan). The attempt was led by Major-General Akbar Khan. Akbar Khan had been a hero in Pakistan’s first war against India over the Kashmir issue in 1948. The war had ended in a stalemate after the United Nations (UN) intervened. Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan accepted the UN’s peace plan.

Akbar Khan was furious. He was an admirer of Turkey’s nationalist leader Kamal Ataturk (d. 1938). In 1950, when the outgoing military chief of Pakistan, General Douglas Gracey (a Briton) was handing over the reins of the military to its new chief, Ayub Khan, he told him that Akbar was part of a group of ‘Kamalests’ in the army and should be watched.

Akbar Khan’s wife was close to the country’s left-wing intelligentsia. She was also on good terms with the Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP). When Akbar Khan began to talk about a nationalist coup against the Liaquat regime with some sympathetic officers, his wife suggested that the CPP be brought on board as well.[1]

It was through her that Akbar contacted some leading CPP members, which included author and Marxist ideologue, Sajjad Zaheer, and famous Urdu poet and journalist, Faiz Ahmed Faiz. Even though Akbar had insisted that his coup would be ‘nationalistic’ in essence, he asked the CPP to help him mobilise the masses (through the party’s student and labour unions). He also agreed to carry out socialist reforms (after the coup).

Twelve military officers, three members of the CPP, and Akbar’s wife become the core group which was to navigate the coup. The plan was to take over strategic state and government buildings and the radio stations with the help of rebel battalions and regiments, and the military chief was to be arrested along with the PM. Power was to be handed over to a ‘revolutionary military junta.’

But the coup plan collapsed when one of Akbar Khan’s confidants, a police officer, leaked the plan to the government. Eleven military officers and four civilians were arrested, including Akbar’s wife. The wife was, however, released, but Akbar, along with all other plotters were given long jail sentences. Sajjad Zaheer was sent back to India from where he had arrived in 1948 to organise the CPP.

All the arrested men were released six years later in 1957. Zafarullah Poshni, who was an army captain at the time and was also arrested, wrote that the plan was always doomed to failure. Akbar was a boastful character and so was his wife. Those who were arrested claimed that Ayub and Liaquat were forced by the US to use the episode to nip communism in Pakistan in the bud.

Major General Akbar Khan

Sajjad Zaheer and Faiz Ahmad Faiz.

The second such attempt which was foiled was made in 1973 against the government of ZA Bhutto. Bhutto’s left-leaning and populist Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) had come to power in December 1971 after East Pakistan separated and became an independent country. The PPP had swept the 1970 elections in West Pakistan.

The coup plan was hatched by a group of officers who had actually paved the way for Bhutto to come to power. After a vicious civil war between the Pakistan army and militant Bengali nationalists saw East Pakistan become Bangladesh, these officers had forced the end of the Yahya Khan dictatorship.

They asked General Yahya to resign and hand over power to Bhutto, unless he wanted to be removed through an officer’s coup. Yahya resigned. However, weary of ‘activist officers,’ the Bhutto regime began to systematically remove them. Bhutto described them as ‘Bonapartists.’[2]

Enraged by the ploy, and believing that officers who had been weak and corrupt during the East Pakistan war were being retained, the rebel group began to plot a coup d’etat against Bhutto with the help of sympathetic officers and soldiers. One of the leading plotters was Brigadier FB. Ali. He had originally been a Bhutto supporter, and was one of the officers who had forced Yahya to resign.

He turned against the Bhutto regime after it began to dismiss many of his colleagues. In 1972, the regime dismissed Ali as well. Noticing that the regime’s actions had created resentment among many officers, Brig. Ali, along with Major Farouk Adam Khan, Squadron Leader Ghous, Colonel Aleem Afridi and Lt. Colonel Tariq Rafi began plotting a coup to oust Bhutto.[3]

It is not known what sort of a government they were planning to install as a replacement, but evidence has surfaced that they were looking to set up a military junta populated by officers who would also see the removal of the generals elevated by Bhutto. According to their lawyer, SM Zaffar, these officers believed that East Pakistan was lost because the military and governments of Pakistan were not Islamic.

Colonel Afridi quietly backed out from the plan and then informed the military’s top leadership about it. The conspirators were arrested, court martialed and jailed. The alleged conspirators were handed the death sentence that was then commutated to life imprisonment. The accused were eventually released in 1978. Ironically, the court martial proceedings were conducted by a Lieutenant General called Ziaul Haq. Four years later, he was made the army chief by Bhutto. In July 1977, he toppled Bhutto in a coup. It was during his dictatorship that the sentenced men were released.

Brigadier FB Ali.

The next failed coup attempt came in 1980. This was against the Ziaul Haq dictatorship which itself was established through a reactionary military coup in July 1977. This attempt was led by Tajammul Hussain Malik, a two-star general in the Pakistan army. One of the few heroes to emerge from the 1971 East Pakistan debacle, Malik was forcibly retired in 1976 by General Ziaul Haq for being a threat to the regime of ZA Bhutto. During his dismissal of Malik, Zia told him he was a ‘fanatic’ and could not be trusted.[5]

Outraged by his ‘forced retirement,’ he planned to oust the Bhutto regime. The plan was aborted when Malik could not gather enough support from serving officers.[6]

A few months later, General Zia toppled Bhutto and declared martial law. Malik, however, returned to the scene in 1980, this time to plot a coup against the Zia regime. He managed to bag the backing of some senior officers, including his son, and planned to assassinate Zia during Pakistan’s Republic Day parade on March 23, 1980.

The plan was to eliminate Zia and install a radical ‘Islamic’ military junta which would replace Zia’s ‘fake Islamic regime’ with ‘a genuine one.’[6] It is not known what a ‘genuine Islamic regime’ meant to the plotters. But in a 2001 interview he described it as a regime run on the principles of the ‘Khulafa-e-Rashdeen.’ The plot was leaked shortly before going into implementation, and the plotters were all arrested. They were given stern jail sentences, including life imprisonment. They were released in 1988 after the demise of Ziaul Haq and the election of Benazir Bhutto as prime minister.

Tajammul Hussain Malik.

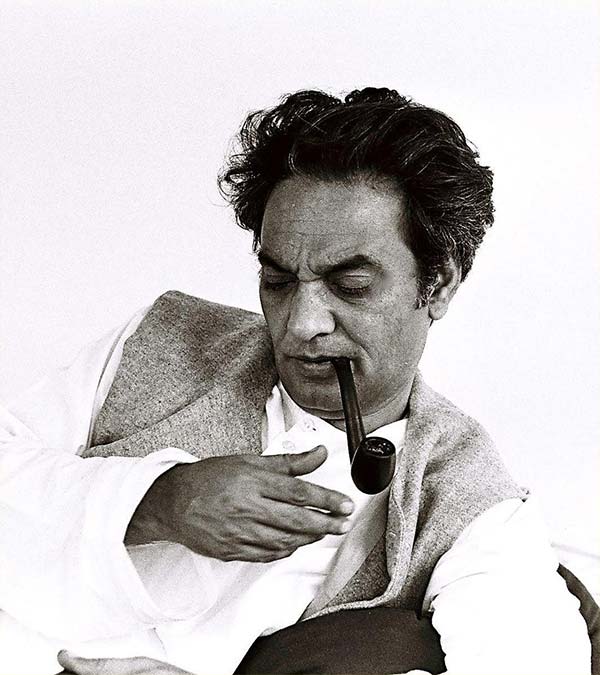

Four years later, in 1984, Zia faced another coup attempt. This time it came from the left. The plot had its roots in 1982 in Lahore when two majors in the Pakistan army met with lawyer, philosopher and Marxist ideologue, Raza Kazim at his residence. Kazim had been in jail a year before for authoring a pamphlet against Ziaul Haq. The majors began expressing their disgruntlement towards the Zia regime, but did not inform him that they were planning to organise a coup against him.

The majors, along with a member of the Pakistan progressive intelligentsia, Ali Mehmood, continued to secretly meet Raza. He was also contacted by Mustafa Khar, a former minister in the ZA Bhutto regime and a senior member of Bhutto’s party. He had flown into exile to the UK after Zia’s 1977 coup. Khar informed Kazim that the majors could be trusted and requested him to help them bring down Zia. Kazim was asked (by the majors) to talk to some other anti-Zia officers about history, philosophy and politics.

In late 1982, Khar and one of the majors, Major Aftab, told Kazim that they were collecting funds to organise exiled Pakistani activists in the UK. They told him that the money would also be used to whip up protests against the Zia dictatorship in Pakistan.

Kazim was a successful lawyer, and he agreed to hand them Rs. 20,000. In total, he gave the plotters over Rs. 90,000. This is when he was eventually told that all this was being done to plan a coup d’etat against the Zia regime.[8]

Decades later, Kazim told the Pakistan monthly magazine, Herald, that the plotters were planning to topple Zia and establish a populist military regime (headed by Major Aftab). Khar had suggested to the plotters that Kazim be given an important post in the new regime and be made its main ideologue.

Raza Kazim.

But the plotters suddenly discontinued their interaction with Kazim. He was already having second thoughts about the whole plan because he thought Major Aftab was a megalomaniac who saw himself as being some kind of a messiah. It was only a year later, in 1984, that Kazim realised that the coup had been planned but was nipped in the bud by military spooks. All the conspirators were arrested, including Kazim. Khar was still in the UK.

They were all given stiff jail sentences, but were released in 1988 by the first Benazir Bhutto regime. It is not known exactly how the plotters had planned to pull off the coup and how many officers were involved. But according to Kazim, over 500 military officers and soldiers were interrogated.[9]

The next failed coup attempt emerged in 1995 against the second Benazir Bhutto regime. It included a group of officers who were close to the Zia regime which had folded in 1988 after his demise. Zia’s appointees in the military had been suspicious of Benazir even when her party had won the first post-Zia election in 1988. They feared that her regime would rollback Pakistan’s nuclear program and Zia’s ‘Islamisation’ policies.

Fears of this nature grew when she returned as PM in 1993. In 1995, Brig. Zaheer Abbasi, Brigadier Mustansir Billa and the Islamic militant Qari Saifullah were arrested by the military high command and accused of planning to overthrow the Benazir government through a coup d’detat.[10] The officers were allegedly planning to launch a coup against what they believed was a ‘liberal and corrupt regime’ hell bent on rolling back Pakistan’s nuclear program and neutralising Zia’s Islamisation project.

After the coup, they planned to impose a strict Islamic set-up and dismiss the then military chief, General Abdul Waheed Kakar. It was actually Gen. Kakar who first discovered the plot through military intelligence. He got the plotters arrested and informed PM Bhutto. The military spooks told Karkar that the mentioned officers were planning to launch a military coup against him and Benazir in collusion with a militant religious outfit that was being funded by the renegade Saudi millionaire, Osama Bin Laden. They had planned to assassinate her and dismiss the army chief.

Brigadier Billa.

Qari Saifullah

In 2012, the Pakistan military announced that it had arrested Brigadier Ali Khan and four other officers for having links with the banned Pan-Islamist outfit, Hizbut Tahrir (HuT).[11] A military court convicted Brigadier Ali Khan, Major Sohail Akbar, Major Jawad Baseer, Major Inayat Aziz and Major Iftikhar for having links with HuT and sentenced them to rigorous imprisonment for terms ranging from 5 years to 18 months. Even though the military didn’t make any mention of a coup attempt, many believe that the officers were planing an ‘Islamic coup’ against the Zardari regime and the military high command which, at the time, was being headed by General Ashfaq Pervez Kayani.

According to a detailed report in Dawn, back in 2003, HuT established links with about 13 commandos of the army’s Special Services Group (SSG). Then in 2009 officers up to the ranks of lieutenant colonel faced court martial for links with HuT and in 2011 a brigadier faced the same charges. In two of these incidents the same HuT members approached the army officers in 2009 and 2011. According to military intelligence documents quoted by Dawn, HuT activists Abdul Qadir and Ahmed, a doctor, were found to have links with Lt-Col Shahid Bashir in 2009 and Brig Ali Khan in 2011.

The documents revealed that both activists of the banned outfit had used the same techniques for establishing links with Lt-Col Bashir and Brig Ali Khan as they developed relations with the officers through common friends and then used the two officers to approach other army officers. The plan was to initiate a mutiny in the military that would lead to an officers coup and put Pakistan at the centre of an emerging international caliphate.

Brigadier Ali Khan.

[1] Z. Poshni: Prison Interlude - The Last Eyewitness Account of the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case (Oxford University Press, 2019).

[2] R. Jetly: Pakistan in Regional and Global Politics (Routledge, 2012)

[3] V. Nasr: The Vanguard of the Islamic Revolution (University of California Press, 1994).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Tajammul Hussain Malik by Agha Amin (PAKPOTPOURRI, 2001).

[6] TH Malik: The Story Of My Struggle (Jang Publishers, 1991).

[7] Raza Kazim interview with S. Ijaz (Herald, September, 2014)

[8] S. Ijaz. op. cit.

[9] Ibid.

[10] L. Ziring: Pakistan at the Cross Currents of History (Oxford University Press, 2004)

[11] Dawn, 29 Oct. 2012.