In 1896, an Islamic scholar presented Sir Syed Ahmad Khan the manuscript of a book that he had written. Days later, Sir Syed, who had by then established himself as one of South Asia’s most prominent Muslim educationists and reformers, returned the manuscript to the author and advised him not to get it published. The author was Maulana Sayyid Mumtaz Ali, a graduate of a famous seminary in Deoband.

Islamic scholars and clerics who had graduated from this seminary were largely opposed to the ideas of social, economic and religious reforms advocated by men such as Sir Syed Ahmad Khan. The ‘Deobandi,’ as these ulema began to be referred to, were Sunni theologians who severely criticised the manner in which Islam had been practiced and preached in India. They believed that the faith had been hybridised through the adoption of non-Islamic ideas and rituals, and that this was a major factor behind the gradual decline of Muslim rule in India.

The 19th century was a tumultuous period for the Muslims and Hindus of India. Although the failure of the 1857 uprising against British colonial rule spelled some serious set-backs for both the communities, it also witnessed a prolific, even frantic, intellectual activity among many Hindu and Muslim scholars and theologians.

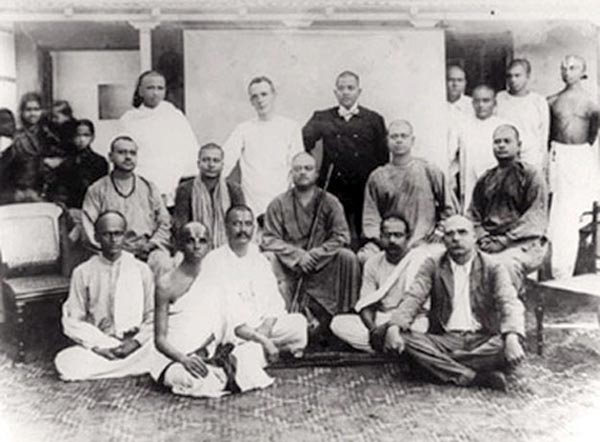

A prominent Hindu reformist movement by the name of Arya Samaj emerged, which attempted to organise the scattered and diversified nature of Hinduism into a cohesive whole. The idea was to propagate an ancient Vedic form of Hinduism which the Samaj claimed was originally monolithic and ‘more pristine.’[1]

Initial British understanding of Hinduism was of a faith that was a collection of superstitions and certain unsavoury traditions, such as the caste system and sati (a former practice in India whereby a widow threw herself on to her husband’s funeral pyre).

Samaj ideologues responded to this by claiming that Hinduism was a highly evolved faith that had been ‘contaminated’ when the Hindus lost political power to Muslim invaders from the 12th century onward.

Samaj scholars explained ‘original’ (i.e. Vedic) Hinduism as an enlightened article of faith. The Samaj also claimed that the Muslims and Christians of India were originally Hindu but had been converted to Islam and Christianity. The Samaj often launched ‘re-conversion’ campaigns.[2] It is within this scholarly and evangelical movement that one can also find the roots of Hindu nationalism.

Similar reformist movements also emerged among the 19th-century Muslim minority of India. There was the ‘modernist’ scholarly tendency pioneered by men such as Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, Altaf Hussain Hali, Chiragh Ali, and Syed Ameer Ali, all of who advocated a rationalist and contemporary interpretation of Islam’s sacred texts and the adoption of modern education and science. This tendency insisted that Islam was inherently compatible with contemporary sciences, economics and many aspects of the emerging social modernity.

Another Muslim reformist tendency that emerged during the same period rejected this narrative. Instead, it understood the decline of the social, economic and political status of the Muslims of India as a consequence of Muslims not following their faith the way they were supposed to. Therefore, Deobandi scholars and clerics were in the forefront of not only attacking those who continued to follow Islam as it had been developing in India since the 12th century; but they also took to task the ‘Islamic modernism’ of the likes of Sir Syed.

Deobandi ulema and those belonging to the Ahel-e-Hadith (a school of thought inspired by ‘Wahabism’) preached strict implementation of Islamic tenets and rites. They also called for the eradication of rituals which they believed had been adopted by Muslims from other religions.

So what disturbed Sir Syed when he read the manuscript given to him by Maulana Sayyid Mumtaz Ali? The manuscript detailed the social and domestic condition of Muslim women in India and how this condition should be addressed and altered. Sir Syed found the Maulana’s observations and suggestions too stark and radical. In the context of 19th century India, much of what Mumtaz was advocating was decades ahead of its time. To Sir Syed, the book, if published, could be used by the ulema to sharpen their arguments against the kind of a modernist Islam Sir Syed and his colleagues were attempting to construct and propagate.

The irony is, even though Maulana Mumtaz came from a conservative Deobandi background, and unlike Sir Syed, he wasn’t that well aquatinted with European ideas, he still gravitated towards what Sir Syed had been prescribing. Just as scholars such as Chiragh Ali and Ameer Ali and the poet, Altaf Hussain Hali had taken Sir Syed’s ideas forward, Mumtaz too wanted to do the same with his book.

Also, since Sir Syed and his aforementioned colleagues had already covered a plethora of social, economic and theological topics in their bid to construct a modernist strand of Islam which could aid Muslims adjust to the many changes being introduced by the British, Mumtaz decided to do the same by entirely concentrating on the status of Muslim women in this strand and zeitgeist.

To Mumtaz, the reforms being suggested by Sir Syed needed to include Muslim women as well. It wasn’t that Sir Syed and his colleagues had completely ignored this. In their writings they understood Muslim women as perpetrators of false customs, and their ‘ignorance’ as a potential cause of downfall for successive generations.[3] They agreed that to address this ‘ignorance’ would help correct the ‘backwardness’ of Muslim society and ensure social progress, as it was perceived that women’s roles as mothers and wives, affected the children and husband within the household, which in turn affected society and the Muslim community at large.[4]

After a long stay in London, Sir Syed had returned to India to write that he was impressed by the rights given to women in Europe and how this had contributed to the overall rise of European nations. Yet, despite the fact that he was unafraid to challenge traditionalist and conservative Muslims by insisting that Islam’s holy texts should be understood allegorically (instead of literally) and a rational approach and scientific mindset should guide a Muslim to follow his faith and life, he decided not to spend too much effort on defining how such an approach was to impact the behaviour and position of India’s Muslim women.[5]

Sir Syed’s reaction to Mumtaz’s manuscript suggests that he was not that keen to further antagonise his opponents, especially on the issues of women and their place in a transformational society. But despite Sir Syed’s reservations, Mumtaz went ahead and published the book. He titled it, Huqooq-e-Niswan (Rights of Women). The book was published in 1898 shortly after Sir Syed’s demise.

The book, penned in Urdu, is remarkably far-sighted in that Mumtaz highlights certain women-related issues that have only now become the subject of open discussion in the larger Muslim world. And yet, this book has only rarely been reprinted. In 1967, an abridged translation of the book was made available by the well-known academic and author Aziz Ahmad.

Maulana Mumtaz wrote that Islam treats men and women equally because “physical strength is no criterion for superiority.” He added, “Indeed, women have to perform certain biological functions for which their nervous systems are conditioned, but this is not a proof of their intellectual or biological inferiority.”

He wrote that the anti-women perception associated with Islam was the outcome of ancient interpretations of Islam’s sacred texts and was influenced by the antique customary laws that the exegetes were following and living under during that period. In other words, such commentaries were time-bound. He insisted that ancient interpretations of the sacred texts have nothing to do with the true spirit of Islam.

On the allowance of polygamy in these texts, Mumtaz argued that when the Muslim holy book says that a man cannot take care of all his wives equally, it is actually cautioning against having more than one wife.

Mumtaz further wrote that “(Muslim) female education was a historical necessity.” On the criticism of the time’s ulema that educated women become “immoral,” Mumtaz pointed out that immorality is not due to educated women, but “mainly because of the distorted impulses of men who are used to segregation.” He predicted that this mindset would change with time.

Without openly advocating that women seek their husbands for themselves, Mumtaz wrote that, “marriages in Muslim India are arranged and loveless.” He added that since most Muslim women were uneducated, they accepted such marriages as their fate and did not know how to address “the tyranny of their husbands” which might be the result in such situations.

On purdah or veiling for women, Mumtaz clarified that the Islamic concept of purdah is simply about observing modesty by both men and women. He wrote that the sacred verses dealing with this concept were directly addressing the 6th and 7th century Arab society and “are thus only relevant to that age and time.”

He then penned a rather interesting observation by stating that the kind of purdah being practised by Indian Muslim women in his time (the 19th century) “was a fairly recent development.” Here he is alluding to the burqa.

Maulana Mumtaz was writing in the 19th century so one can assume that the burqa is a 19th -century creation, just as other forms of veiling such as the hijab is a 20th-century innovation. Mumtaz added that “forcing the veil on women is a flagrant injustice” and against the faith’s spirit and meaning of morality.

On the criticism he faced by those who bemoaned that the emancipation of women would lead them to commit immoral acts, Mumtaz retorted that instead of blaming the women, action should be taken against those who treat them as an object of immorality.

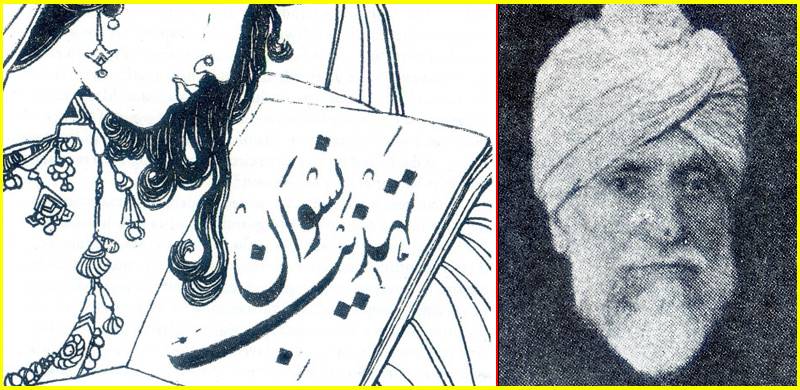

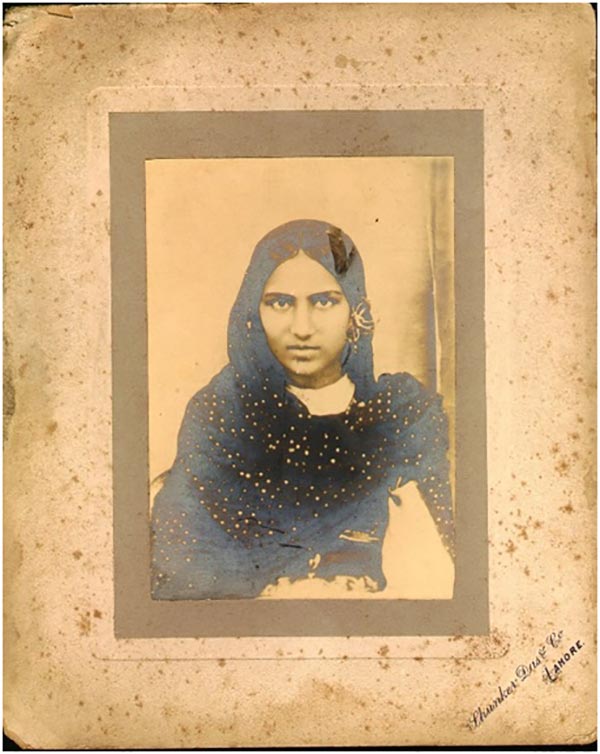

According to Aziz Ahmad, observations and opinions that he shared in his book were mostly provided by his wife, Muhammadi Begum, who could not pen them herself due to her gender. Nevertheless, both Mumtaz and Muhammadi Begum launched a magazine Tehzib-un-Niswan of which Muhammadi Begum became the editor. The magazine, published from Lahore, was entirely dedicated to discussing social, domestic and health issues related to Muslim women in India. Women were encouraged to contribute articles, poems and short-stories to the magazine, which they did. Some published them under their real names while others found it prudent to use pen names.

In his book, Mumtaz used Quranic and Hadith sources, different schools of Islamic law and ‘Aristotelian logic’ to counter the reasons given by conservatives for male superiority. He called such reasons "mardon ki jhooti fazeelat" (the false superiority of men over women).[6]

In response to the commonly used argument that men are physically stronger than women and therefore superior, Mumtaz wrote that ‘donkeys are stronger than men so by that same logic we should also conclude that the former are superior to the latter.’[7]

Mumtaz Ali wrote that he was well aware that his book will be ‘attacked by people blinded by their adherence to false customs.’ He claimed that those who will attack him, no matter how pious they want the world to see them as, do not understand the true spirit of the faith they were pretending to follow.

No Muslim publishers — including those who had otherwise happily published tomes by Sir Syed and his colleagues — were willing to publish Mumtaz’s book. Mumtaz had to publish it himself. It did create a ruckus of sorts among sections of the traditionalist and conservative ulema. But this was short-lived because Mumtaz did not publish any more copies after 1898. An English translation of the book appeared in 1967, before quickly vanishing. The original Urdu version was not republished until over 120 years later when the Indian Muslim author, Asghar Ali Engineer, managed to acquire an original copy of the book from a library in the United States and got it republished.

[1] JS Llewellyn: The Arya Samaj as a Fundamentalist Movement: A Study in Comparative Fundamentalism (Manohar Publishers & Distributors, 1993) p.97

[2] Andrew Buckser, Stephen D. Glazier (eds): The Anthropology of Religious Conversion (Rowman & Littlefield, 2003) p.49

[3] Islamic Reform and Female Education: Social Reforms for Muslim Women in Late Colonial India: S. Bhayat (December 18, 2016)

[4] Ibid

[5] Ibid

[6] Maulana’s feminist text: M Ali Jan (The News on Sunday, March 26, 2017)

[7] Ibid

Islamic scholars and clerics who had graduated from this seminary were largely opposed to the ideas of social, economic and religious reforms advocated by men such as Sir Syed Ahmad Khan. The ‘Deobandi,’ as these ulema began to be referred to, were Sunni theologians who severely criticised the manner in which Islam had been practiced and preached in India. They believed that the faith had been hybridised through the adoption of non-Islamic ideas and rituals, and that this was a major factor behind the gradual decline of Muslim rule in India.

The 19th century was a tumultuous period for the Muslims and Hindus of India. Although the failure of the 1857 uprising against British colonial rule spelled some serious set-backs for both the communities, it also witnessed a prolific, even frantic, intellectual activity among many Hindu and Muslim scholars and theologians.

A prominent Hindu reformist movement by the name of Arya Samaj emerged, which attempted to organise the scattered and diversified nature of Hinduism into a cohesive whole. The idea was to propagate an ancient Vedic form of Hinduism which the Samaj claimed was originally monolithic and ‘more pristine.’[1]

Initial British understanding of Hinduism was of a faith that was a collection of superstitions and certain unsavoury traditions, such as the caste system and sati (a former practice in India whereby a widow threw herself on to her husband’s funeral pyre).

Samaj ideologues responded to this by claiming that Hinduism was a highly evolved faith that had been ‘contaminated’ when the Hindus lost political power to Muslim invaders from the 12th century onward.

Samaj scholars explained ‘original’ (i.e. Vedic) Hinduism as an enlightened article of faith. The Samaj also claimed that the Muslims and Christians of India were originally Hindu but had been converted to Islam and Christianity. The Samaj often launched ‘re-conversion’ campaigns.[2] It is within this scholarly and evangelical movement that one can also find the roots of Hindu nationalism.

Similar reformist movements also emerged among the 19th-century Muslim minority of India. There was the ‘modernist’ scholarly tendency pioneered by men such as Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, Altaf Hussain Hali, Chiragh Ali, and Syed Ameer Ali, all of who advocated a rationalist and contemporary interpretation of Islam’s sacred texts and the adoption of modern education and science. This tendency insisted that Islam was inherently compatible with contemporary sciences, economics and many aspects of the emerging social modernity.

Another Muslim reformist tendency that emerged during the same period rejected this narrative. Instead, it understood the decline of the social, economic and political status of the Muslims of India as a consequence of Muslims not following their faith the way they were supposed to. Therefore, Deobandi scholars and clerics were in the forefront of not only attacking those who continued to follow Islam as it had been developing in India since the 12th century; but they also took to task the ‘Islamic modernism’ of the likes of Sir Syed.

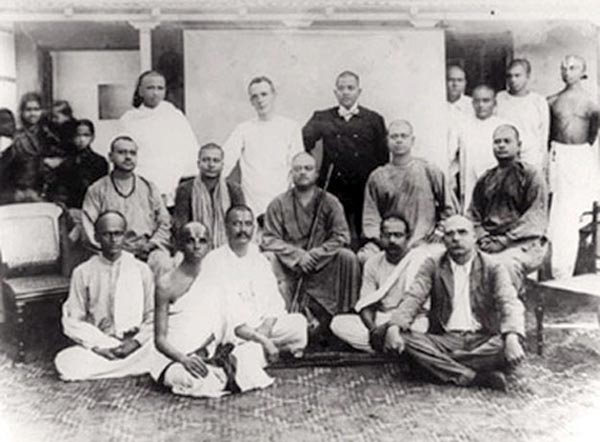

The Arya Samaj.

Deobandi ulema and those belonging to the Ahel-e-Hadith (a school of thought inspired by ‘Wahabism’) preached strict implementation of Islamic tenets and rites. They also called for the eradication of rituals which they believed had been adopted by Muslims from other religions.

So what disturbed Sir Syed when he read the manuscript given to him by Maulana Sayyid Mumtaz Ali? The manuscript detailed the social and domestic condition of Muslim women in India and how this condition should be addressed and altered. Sir Syed found the Maulana’s observations and suggestions too stark and radical. In the context of 19th century India, much of what Mumtaz was advocating was decades ahead of its time. To Sir Syed, the book, if published, could be used by the ulema to sharpen their arguments against the kind of a modernist Islam Sir Syed and his colleagues were attempting to construct and propagate.

The irony is, even though Maulana Mumtaz came from a conservative Deobandi background, and unlike Sir Syed, he wasn’t that well aquatinted with European ideas, he still gravitated towards what Sir Syed had been prescribing. Just as scholars such as Chiragh Ali and Ameer Ali and the poet, Altaf Hussain Hali had taken Sir Syed’s ideas forward, Mumtaz too wanted to do the same with his book.

Also, since Sir Syed and his aforementioned colleagues had already covered a plethora of social, economic and theological topics in their bid to construct a modernist strand of Islam which could aid Muslims adjust to the many changes being introduced by the British, Mumtaz decided to do the same by entirely concentrating on the status of Muslim women in this strand and zeitgeist.

To Mumtaz, the reforms being suggested by Sir Syed needed to include Muslim women as well. It wasn’t that Sir Syed and his colleagues had completely ignored this. In their writings they understood Muslim women as perpetrators of false customs, and their ‘ignorance’ as a potential cause of downfall for successive generations.[3] They agreed that to address this ‘ignorance’ would help correct the ‘backwardness’ of Muslim society and ensure social progress, as it was perceived that women’s roles as mothers and wives, affected the children and husband within the household, which in turn affected society and the Muslim community at large.[4]

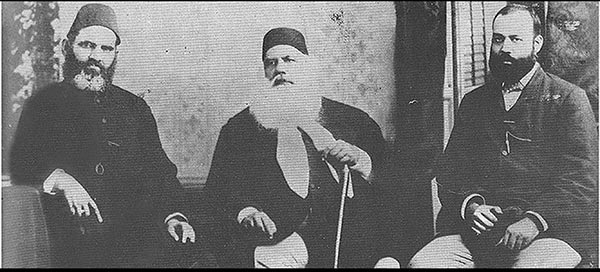

After a long stay in London, Sir Syed had returned to India to write that he was impressed by the rights given to women in Europe and how this had contributed to the overall rise of European nations. Yet, despite the fact that he was unafraid to challenge traditionalist and conservative Muslims by insisting that Islam’s holy texts should be understood allegorically (instead of literally) and a rational approach and scientific mindset should guide a Muslim to follow his faith and life, he decided not to spend too much effort on defining how such an approach was to impact the behaviour and position of India’s Muslim women.[5]

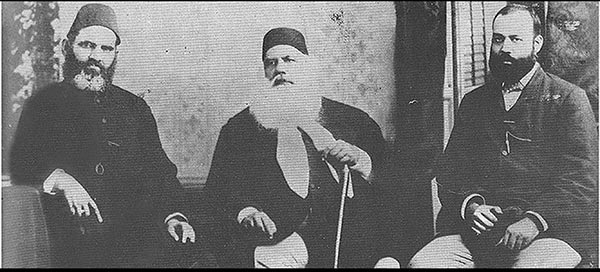

Sir Syed with his sons.

Sir Syed’s reaction to Mumtaz’s manuscript suggests that he was not that keen to further antagonise his opponents, especially on the issues of women and their place in a transformational society. But despite Sir Syed’s reservations, Mumtaz went ahead and published the book. He titled it, Huqooq-e-Niswan (Rights of Women). The book was published in 1898 shortly after Sir Syed’s demise.

The book, penned in Urdu, is remarkably far-sighted in that Mumtaz highlights certain women-related issues that have only now become the subject of open discussion in the larger Muslim world. And yet, this book has only rarely been reprinted. In 1967, an abridged translation of the book was made available by the well-known academic and author Aziz Ahmad.

Maulana Mumtaz wrote that Islam treats men and women equally because “physical strength is no criterion for superiority.” He added, “Indeed, women have to perform certain biological functions for which their nervous systems are conditioned, but this is not a proof of their intellectual or biological inferiority.”

He wrote that the anti-women perception associated with Islam was the outcome of ancient interpretations of Islam’s sacred texts and was influenced by the antique customary laws that the exegetes were following and living under during that period. In other words, such commentaries were time-bound. He insisted that ancient interpretations of the sacred texts have nothing to do with the true spirit of Islam.

On the allowance of polygamy in these texts, Mumtaz argued that when the Muslim holy book says that a man cannot take care of all his wives equally, it is actually cautioning against having more than one wife.

Mumtaz further wrote that “(Muslim) female education was a historical necessity.” On the criticism of the time’s ulema that educated women become “immoral,” Mumtaz pointed out that immorality is not due to educated women, but “mainly because of the distorted impulses of men who are used to segregation.” He predicted that this mindset would change with time.

Without openly advocating that women seek their husbands for themselves, Mumtaz wrote that, “marriages in Muslim India are arranged and loveless.” He added that since most Muslim women were uneducated, they accepted such marriages as their fate and did not know how to address “the tyranny of their husbands” which might be the result in such situations.

On purdah or veiling for women, Mumtaz clarified that the Islamic concept of purdah is simply about observing modesty by both men and women. He wrote that the sacred verses dealing with this concept were directly addressing the 6th and 7th century Arab society and “are thus only relevant to that age and time.”

He then penned a rather interesting observation by stating that the kind of purdah being practised by Indian Muslim women in his time (the 19th century) “was a fairly recent development.” Here he is alluding to the burqa.

Maulana Mumtaz was writing in the 19th century so one can assume that the burqa is a 19th -century creation, just as other forms of veiling such as the hijab is a 20th-century innovation. Mumtaz added that “forcing the veil on women is a flagrant injustice” and against the faith’s spirit and meaning of morality.

On the criticism he faced by those who bemoaned that the emancipation of women would lead them to commit immoral acts, Mumtaz retorted that instead of blaming the women, action should be taken against those who treat them as an object of immorality.

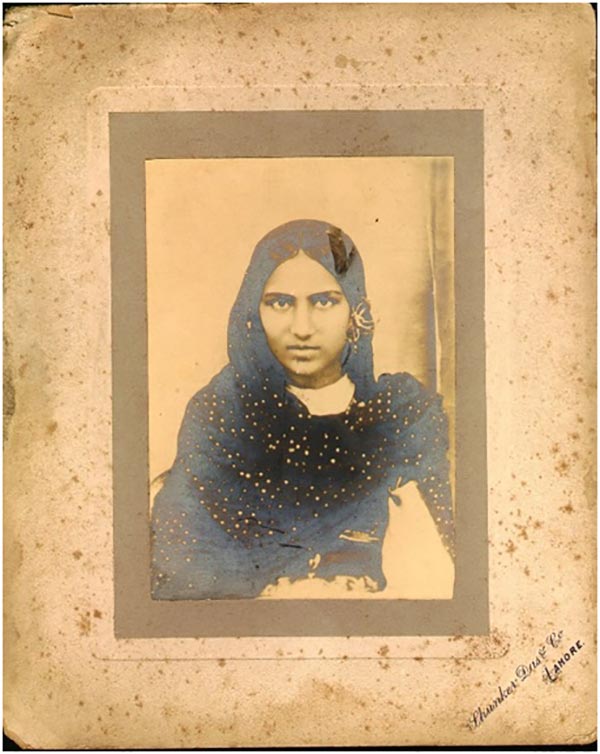

According to Aziz Ahmad, observations and opinions that he shared in his book were mostly provided by his wife, Muhammadi Begum, who could not pen them herself due to her gender. Nevertheless, both Mumtaz and Muhammadi Begum launched a magazine Tehzib-un-Niswan of which Muhammadi Begum became the editor. The magazine, published from Lahore, was entirely dedicated to discussing social, domestic and health issues related to Muslim women in India. Women were encouraged to contribute articles, poems and short-stories to the magazine, which they did. Some published them under their real names while others found it prudent to use pen names.

Muhammadi Begum.

Cover of the first issue of Tehzib-un-Niswan.

In his book, Mumtaz used Quranic and Hadith sources, different schools of Islamic law and ‘Aristotelian logic’ to counter the reasons given by conservatives for male superiority. He called such reasons "mardon ki jhooti fazeelat" (the false superiority of men over women).[6]

In response to the commonly used argument that men are physically stronger than women and therefore superior, Mumtaz wrote that ‘donkeys are stronger than men so by that same logic we should also conclude that the former are superior to the latter.’[7]

Mumtaz Ali wrote that he was well aware that his book will be ‘attacked by people blinded by their adherence to false customs.’ He claimed that those who will attack him, no matter how pious they want the world to see them as, do not understand the true spirit of the faith they were pretending to follow.

No Muslim publishers — including those who had otherwise happily published tomes by Sir Syed and his colleagues — were willing to publish Mumtaz’s book. Mumtaz had to publish it himself. It did create a ruckus of sorts among sections of the traditionalist and conservative ulema. But this was short-lived because Mumtaz did not publish any more copies after 1898. An English translation of the book appeared in 1967, before quickly vanishing. The original Urdu version was not republished until over 120 years later when the Indian Muslim author, Asghar Ali Engineer, managed to acquire an original copy of the book from a library in the United States and got it republished.

[1] JS Llewellyn: The Arya Samaj as a Fundamentalist Movement: A Study in Comparative Fundamentalism (Manohar Publishers & Distributors, 1993) p.97

[2] Andrew Buckser, Stephen D. Glazier (eds): The Anthropology of Religious Conversion (Rowman & Littlefield, 2003) p.49

[3] Islamic Reform and Female Education: Social Reforms for Muslim Women in Late Colonial India: S. Bhayat (December 18, 2016)

[4] Ibid

[5] Ibid

[6] Maulana’s feminist text: M Ali Jan (The News on Sunday, March 26, 2017)

[7] Ibid