But even before Alavi’s systematic dissection of the Movement, eminent scholar and professor of political science, late Khalid bin Sayeed had suggested the same in his 1968 book Pakistan: The Formative Years. However, to Sayeed, the aforementioned Movement not only stirred religious passions of the region’s Muslims, but also of the Hindus. Thus, in view of Sayeed’s assertions in this context, one can conclude that the roots of both Muslim and Hindu militancy sprouted from the seeds first sown by the Khilafat Movement.

In 1919, when the already depleted Ottoman regime in Turkey was defeated by a British-led alliance during the First World War, the ulema of India, who till then had largely remained stationed in their mosques and madrasahs, poured out to agitate against the possible dismantling of the Ottoman Empire.

The resultant Khilafat Movement, which had begun to ferment during the last years of the First World War, managed to capture the attention and interest of a large number of Indian Muslims.

Some sixty years before the Ottoman regime allied itself with the Germans against the British-led alliance in the First World War, it was actually cultivating amicable relations with the British. The regime had begun to lose territory and influence in the Muslim world and wanted to retain its status as the only legitimate caliphate. During the 1857 Mutiny, the British managed to extract a fatwa from the Ottoman caliph urging the Muslims not to fight against the British.[2] Due to tensions between the British and the Russian monarchy at the time, Britain promoted a pro-Ottoman line. They encouraged loyalty to the Ottoman Caliph among the Indian Muslims.

According to Mubarak Ali, this is how the Indian Muslims slowly started to regard the Ottoman Caliph as the head of Muslim world. During the 19th century emergence of the Pan-Islamism generated by the likes of Jamal Uddin Afghani, the Ottoman Caliph Sultan Abdul Hamid I (1876-1909) tried to use Pan-Islamism to establish his political position in the Muslim world.

Muslim reformist, Sir Sayed Ahmad Khan, realizing the danger of this extra-territorial loyalty, warned the Indian Muslims not to look to the Caliph as their protector or defender. But the Muslims of India became more conscious about the existence of Turkey. They started to relate Islam with Turkey and that any danger to Turkey became the danger to Islam.

19th century Pan-Islamist, Jamal Uddin Afghani. He was seen with suspicion by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan. In turn, Afghani criticized Khan for undermining Pan-Islamism.

The Muslim nationalist party, the All India Muslim League (AIML), which was largely a pluralistic outfit, changed tact due to the pressures exerted by the growing resentment among the emerging Muslim middle-classes against the defeat of the Ottoman forces at the hands of the British.

Pan-Islamists - many of who were also operating from within the secular-nationalist Indian National Congress (INC) - and ulema groups were at the forefront of the Khilafat Movement. The League’s position was being undermined by its inaction in this regard. Feeling sidelined and overwhelmed by the religious passions of the Movement, a leading AIML member, Dr. Ansari, headed a special AIML convention in Delhi in 1918, and invited a group of ulema to the session. However, another core League member, Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman, worried that Muslim politics in India were being mixed with religious passions and that this would dwarf the ‘more real issues’ facing the Muslims.[3]

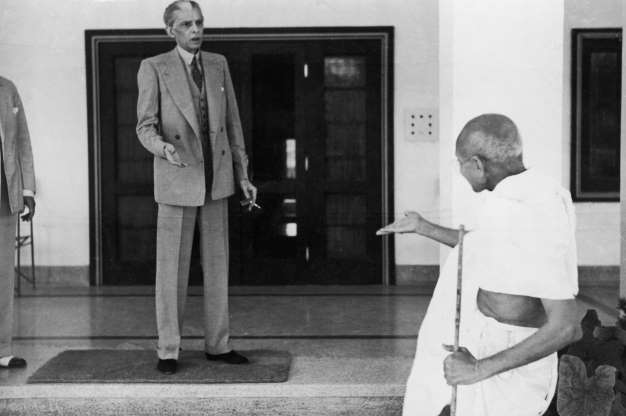

Jinnah too decried Dr. Ansari’s move to make the League enter the fray. Jinnah’s fervent opposition in this regard created a rift within the party. He opposed the Khliafat Movement because he believed that it was destined to fail and end in a disaster for the Indian Muslim and Hindu communities.[4] Jinnah was also not amused when Pan-Islamists such as Mohammad Ali Johar and his brother Shaukat Ali formed the All India Khilafat Committee with a group of ulema and some members of the AIML. In 1920, the Committee managed to attract the interest of the INC which was being guided by the revered Hindu leader and activist, Mahatma Gandhi. Gandhi was already planning to launch a countrywide movement against the British and he saw the Khliafat Movement as an opportunity to mobilize and bring in a large number of Muslims on the side of his own anti-British cause.

Jinnah warned that the Movement would roll back whatever the two communities had managed to extract from the British. He was also concerned about the manner in which the AIML was being undermined and overwhelmed by the Khilfat Committee which, he believed, had become a tool in the hands of the INC and the Pan-Islamists. Jinnah confessed that he was unable to curtail the rapid flow of the movement but continued to advise the Muslims to not be swept away by its populist rise because it was ill-conceived and impractical. In a letter to Gandhi, Jinnah wrote that the Movement was bound to stir untapped religious passions of the masses and would be a disaster to the fate of the Hindus and Muslims of India. Gandhi disagreed.

Jinnah warned Gandhi about the perils of the Khilafat Movement.

As riots and violence broke out and hundreds of Muslims and Hindus were arrested, Jinnah’s faction in the AIML stayed aloof from the Movement. Then, when the intensity of the violence between the protesters and the police increased, a radical Islamic preacher and scholar, Maulana Abdul Bari, asked the Muslims to leave India because it had become a darul harab.[5]

Thousands of young Muslims decided to move to Afghanistan (because it was being ruled by a Muslim amir). Many of the would-be-migrants, however, were robbed and looted by mountain and highway bandits and then turned away by the Afghan regime.[6] And those who returned to India found their homes occupied by their neighbors.[7]

The Muslim-Hindu unity being celebrated by the Khilafat Committee began to erode when the violent currents of the Movement also created opportunities for certain other tense tendencies to emerge within the anarchic scenario that the Movement had generated.

At the start of the Movement, British troops massacred over 350 Indians (mostly Sikh) in Amritsar. Then, at the height of the commotion in 1921, Muslim peasants in India’s Malabar area rose up against their Hindu landlords[8] triggering clashes between the two communities there. Hundreds of Hindus were forcefully converted to Islam[9], before the authorities brutally crushed the uprising, killing and arresting dozens of Muslim peasants.

Soldiers open fire at a rally of Hindu, Muslim and Sikh protesters at the Jallianwalla Bagh in 1919 during the Movement. Hundreds were killed.

Then, in 1922, a violent mob burned alive 22 policemen in Chairi Chaura[10]. This gruesome incident forced Gandhi to pull the INC out of the Movement and also halt his own ‘Non-Corporation Movement.’ Jinnah had raised fears that the Movement had the potential to whip up untapped religious passions of the masses which would be disastrous for the Indians and lead to chaos. This is exactly what happened. Gandhi finally abandoned the Movement. He was criticized for doing so by the Khilafat leadership and also by some members of the INC who quit the party and formed their own Swaraj Party.

The Movement was particularly harmful for the Muslims. Hundreds perished and many Muslim youth (who were encouraged by Pan-Islamists such as Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad and Muhammad Ali, to quit their schools and colleges[11]) became part of a disoriented and rudderless generation. The Movement eventually collapsed when a Turkish nationalist and general, Mustafa Kamal, drove out foreign forces from parts of Turkey, abolished the caliphate, and formed a secular republic based on Turkish nationalism.

In the end of it all, the INC was weakened and most of its top leadership was in jail. AIML was left severely disjointed; and groups of radical Muslim activists and ulema who had risen to prominence during the commotion, fragmented. The Ali brothers departed from their radical Pan-Islamist leanings; whereas other Pan-Islamists, such Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad and former AIML member, Dr. Ansari, became supporters of the INC. Another set of radicals from the Khilafat Committee formed the Majlis-e-Ahrar-e-Islami, a radical Sunni Muslim outfit. Others gallivanted towards the Jamiat Ulema Islam Hind (JUIH) and later, towards the quasi-fascist, Khaksar Tehreek.

For a brief moment, the Hindu-Muslim unity was celebrated by the Khilafat and Non-Cooperation Movements. Paraphernalia (such as this 1922 matchbox) promoted this ‘unity’ by showing flags of the AIML and the Indian Swaraj (self-rule). The unity collapsed in 1923.

A 1920 mock Rs.1 note printed by the Khilafat Committee.

1922: A mob of Hindu and Muslim protesters setting fire to a police station in Chairi Chaura. 22 policemen (all Indian) were burned alive.

Khliafat And Hindu Nationalism

The Movement’s radical currents had swept large numbers of Muslims towards adopting a more militant mindset. After the Movement collapsed in 1924, new militant Islamic outfits emerged. On the other hand, even though Hindu nationalists had refused to take part in both Khilafat and INC’s Non-Cooperation movements, radical Hindu organizations still gained strength. One of the reasons for these not participating in the two movements was that, to Hindu nationalists, Muslims were bigger enemies (of Hindus) than the British.[12]

Till the early 20th century, Hindu nationalists had struggled to come up with a more coherent narrative to convincingly substantiate the whole idea of Hindu nationalism. But when the Khilafat Movement erupted, Hindu nationalists reacted by producing a frenzy of treatises, using myths, revisionist history and narratives of reform -- first imitated in the 19th century by Hindu outfits such as the Arya Samaj -- to furnish a more comprehensible account of Hindu nationalism.

In his 1934 book The Story of My Life, the early Hindu nationalist and author Bhai Parmanand lamented that, when he visited the United States in 1914, many Americans asked him, ‘Are all Hindus Muslim?’

The Indian historian Gyanendra Pandey in his essay for the anthology, Hindus and Others, wrote that, even till the late 19th century, being a Hindu largely meant being an inhabitant of India, no matter what religion he or she belonged to.

Both Hindu and Muslim nationalisms in India have their roots in the aftermath of the failure of the 1857 Mutiny. Nationalism as an idea was largely foreign to both the communities. It was uncannily introduced in the subcontinent by the British. The eminent historian, Ayesha Jalal, in her book Self and Sovereignty, writes that at least one of the reasons behind the emergence of Hindu and Muslim nationalism was the introduction of the holding of a nationwide census by the British, who insisted that the natives declare their faith.

Bhai Parmanand should not have been surprised by what the Americans asked him. The idea of defining the Hindus and Muslims as separate communities of India was still new to those living thousands of miles away. To them, India was Hindustan, and its citizens were Hindu just as America’s citizens were American — be they Christian or otherwise. But Parmanand was aware of the fact that unlike Islam, Judaism or Christianity, Hinduism was a dispersed faith which did not have a centre.

Bhai Parmanand.

According to author and historian Craig A. Lockhard in his book Societies, Networks and Transitions, Hinduism emerged over centuries as a synthesis and fusion of various cultures and beliefs which sprang up in the region. But this synthesis was more cultural and geographical in nature. It wasn’t tied together by a single, overarching theological thread.

The British scholar of religion G.D. Flood writes in his tome An Introduction to Hinduism that the word ‘Hindu’ was first used as a geographical term in the Persian texts of 6th century BCE to describe people who lived beyond River Indus (in present-day Pakistan).

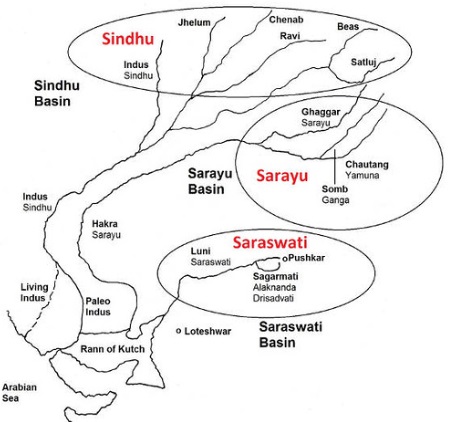

Flood also writes that the Persians formulated this word from the original local name of the Indus, which was Sindhu. According to Indian historian Romila Thapar, the term ‘Sindhu’ was derived from ‘Sapta Sindhu’ mentioned in the Rig Veda — a book of Sanskrit hymns composed between 1500 and 1200 BCE.

The Sapta Sindhu is described as a river in the Rig Veda. The post-7th century Arabs picked up on the word ‘Hindu’ first coined by the Persians to form the word ‘al-Hind’ or ‘Hindustan.’ By this they meant a region inhabited by the people of the Indus.

J.T. O’Connell, in his 1973 essay, ‘The Word Hindu,’[13] writes that it was only in the 16th century CE that the word ‘Hindu’ initially emerged in the context of being a faith. According to him, it is described as a religion in the 16th century Bengali tome Chaitanya Charitamrita which uses the expression, ‘Hindu dharma.’

The Rig-Veda mentions three rivers: Saraswati, the Sarayu and the Sindhu. Sindhu is what is known as Indus in present-day Pakistan.

Gyanendra Pandey wrote that to overcome the realization that Hinduism had never been a cohesive and organized faith and was, in fact, a cultural amalgamation of various beliefs evolving in ancient India, early Hindu nationalists claimed that a majority of non-Hindu people living in the region had originally been Hindu and were converted. On the other hand, also in the 19th century, early Muslim nationalists claimed that their ancestors were non-Indian and had roots in Muslim Arabia and Central Asia.

But the Muslim nationalists had an established monotheist faith to help them concoct a social and political link with Muslim-majority regions elsewhere; the early Hindu nationalists, on the other hand, struggled to formulate a coherent history of Hinduism.

Whereas it was somewhat simpler for 19th century Muslim reformers of India to work with an established monotheist faith with an organized ‘history’ to express their cultural and political separateness, Hindu reformers had to start almost from scratch.

Therefore, early Hindu reformist organisations such as the Arya Samaj (formed in 1875) based their Hindu reformism on the idea that Hinduism, too, was a monotheistic faith which had just one God and that all other deities worshipped in India were just manifestations of this one God (Brahma). The aim was to shape a dispersed cultural synthesis into an organized monotheist faith so that it could be used to form a cohesive Hindu nationalist narrative and polity.

Interestingly, the late Hindu nationalist and intellectual, VD Savarkar, in his quintessential treatise on Hindu nationalism, The Essentials of Hindutva (1923), confronted the aforementioned dilemma by suggesting that the Hindu was a person who was indigenous to the region and followed a faith that was born here. These included all forms of Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism. To him Muslim and Christians of India followed ‘alien faiths’ and there cultures were therefore alien. Interestingly, Savarkar was a declared atheist. So to him Hinduism was a culture informed by the region’s indigenous faiths.

Savarkar wrote the book at the height of the Khilafat Movement and it was clearly a reaction to what he saw was another attempt by the Muslims to subjugate Hinduism (as a culture and polity). Savarkar saw no place for Muslims and Christians in the ‘Hindu nation’ and coming ‘Hindu rashtra’, not unless they openly confess that they were converted.

Jinnah’s caution and position on the Khilafat Movement was vindicated. But the tradition of politics done on the impulse and emotion of the fanatical religious mob had been established in the region. So one can conclude by saying that the radicalization of large segments of Hindu and Muslim polities during the two movements contributed to the many episodes of ‘communal violence’ that followed, leaving Jinnah (who had opposed the Khilafat Movement) no other choice but to demand a separate Muslim state.

[1] Journal of Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East (Vol: 17, Spring 1997).

[2] TW Arnold: The Caliphate (Oxford University Press, 1966) p.137

[3] Mubarak Ali (DAWN, August 28, 2016)

[4] Akbar Ahmad: The Search for Saladin (Routledge, 2005)

[5] Arab term meaning ‘home of war’ (opposite of dar-ul-Islam, meaning home of Islam).

[6] Khursheed Kamal Aziz: The Indian Khilafat Movement (Pak Publishers, 1972) p.272

[7] Akbar Ahmad: The Search for Saladin (Routledge, 2005)

[8] Prabhu Bapu: Hindu Mahasaba in Colonial North India (Routledge, 2013) p.49

[9] Khallid bin Sayeed: Pakistan’s Formative Years (Oxford University Press) p.196

[10] J. Chandra: Gandhiji and Haryana (Usha Publications, 1977) p.13

[11] Khallid bin Sayeed: Pakistan’s Formative Years (Oxford University Press) p.214

[12] C. Jaffrelot: The Hindu Nationalist Movement in India (Columbia University Press, 1996).

[13] Journal of the American Oriental Society (1973) p.340