In its 72-year history, Pakistan has been ruled by four military dictators. Each one, after seizing power ostensibly to save the nation from destruction, managed to convince himself of his indispensability and stayed in power until he was ignominiously thrown out of office. General (who promoted himself later to Field Marshal) Ayub Khan was the first dictator, General Yahya Khan the second, General Zia the third and General Musharraf the fourth.

The inner workings of Ayub’s mind are laid bare in the memoirs of his son, titled “Glimpses into the corridors of power.” In an unusual arrangement, Gohar served as the president’s Aide-de-Camp for many years, giving him unusual access to the top brass and their lieutenants in mufti.

Ten years into his rule, Ayub was suffering from acute heart disease. That was known to a few, including his hand-picked army chief, General Yahya. Gohar warned Ayub that Yahya was planning to depose him. With an attitude of resignation, Ayub responded, “You have served in GHQ and should know that if the Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army gets it into his head to take over, then it is only God above who can stop him.”

Who would have known this better than Ayub? In October 1958, he had deposed the man who had made him chief martial law administrator, Iskander Mirza. Even that deed, Gohar tells us, had Yahya’s finger prints all over it. Yahya had convinced Ayub that Mirza feared all the powers he had placed in Ayub’s hands and planned to arrest him.

However, Gohar reminds us, unlike many others who governed Pakistan after his departure, Ayub gave Mirza a safe passage to London where he continued to earn two Pakistani pensions.

After India attacked Lahore on the 6th of September, 1965, Pakistan hit back with its mailed fist. The First Armored Division commanded by Major-General Naseer Ahmed was sent in to out-flank four Indian divisions in East Punjab and three in Jammu and Kashmir.

Whether this bold maneuver would ever have succeeded will never be known because it ended in ignominy, even though Pakistan had much superior weaponry, including the US-supplied Patton tank. It failed for three reasons:

Afterwards, Naseer told another divisional commander that he wanted to shoot himself. When the news got to the field marshal, he said it would have been nice if Naseer had indeed done so.

Ayub had gradually built up the Pakistani military since taking over as the army chief in 1951. He had succeeded in equipping the military with modern weaponry from the United States, much of it acquired at below-market price and financed with American aid. Indeed, as Gohar tells us, two dozen B-57Bs bombers were provided free of charge. It pained Ayub greatly to see all this go to waste in the war with India, especially when he had emerged victorious in the national elections against Fatima Jinnah.

Gohar implies that Ayub had concluded that the war was a disaster for Pakistan, being based on unfounded assumptions about a Kashmiri uprising and about India sitting still on the international border. But, like a true son, Gohar does not put the blame on his father.

Instead, he points the finger at Ayub’s foreign minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, and the divisional commander in Kashmir. He says Ayub wanted the army to conduct an inquiry into the war. But it was never held because Yahya, then army chief, did not want it done.

Gohar concedes that the celebration of Ayub’s Decade of Development was ill-conceived but places the blame for its observance on the shoulders of the information secretary, Altaf Gauhar. Once again he is absolving his father.

As the Ayubian denouement neared its end, people rioted. Gohar tells us that an advisor suggested that Ayub should kill 5,000 people to restore the writ of the state. However, Ayub replied that he could not even kill 50 chicken, let alone 5,000 people. He added, were he to begin killing people just to stay in power, four times that number would come after him to take revenge.

The fact that Pakistan was not turned into a killing filed on Ayub’s watch speaks of his sagacity and compassion. However, the fact that Ayub had appointed Yahya the army chief a few years earlier spoke poorly of his ability to pick lieutenants.

As events got out of control in East Pakistan in 1971, Ayub counseled Yahya through a back channel that he should negotiate a withdrawal of Pakistani forces with Shaikh Mujib (then Yahya’s prisoner) and convert Pakistan into a confederation. He had rightly concluded that after the army action, it could not survive as a federation.

But Yahya was not in the mood to listen to anyone, least of all to his former mentor. As so often happens in history, when the inevitable happened, Yahya blamed the defeat of the army he commanded on the “treachery of the Indians.” That statement stands out for its originality. There are few instances in history where a defeated general blames his defeat on his enemies. As far as we know, Napoleon did not put the blame for his defeat at Waterloo on the Duke of Wellington.

The inner workings of Ayub’s mind are laid bare in the memoirs of his son, titled “Glimpses into the corridors of power.” In an unusual arrangement, Gohar served as the president’s Aide-de-Camp for many years, giving him unusual access to the top brass and their lieutenants in mufti.

Ten years into his rule, Ayub was suffering from acute heart disease. That was known to a few, including his hand-picked army chief, General Yahya. Gohar warned Ayub that Yahya was planning to depose him. With an attitude of resignation, Ayub responded, “You have served in GHQ and should know that if the Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army gets it into his head to take over, then it is only God above who can stop him.”

Who would have known this better than Ayub? In October 1958, he had deposed the man who had made him chief martial law administrator, Iskander Mirza. Even that deed, Gohar tells us, had Yahya’s finger prints all over it. Yahya had convinced Ayub that Mirza feared all the powers he had placed in Ayub’s hands and planned to arrest him.

However, Gohar reminds us, unlike many others who governed Pakistan after his departure, Ayub gave Mirza a safe passage to London where he continued to earn two Pakistani pensions.

After India attacked Lahore on the 6th of September, 1965, Pakistan hit back with its mailed fist. The First Armored Division commanded by Major-General Naseer Ahmed was sent in to out-flank four Indian divisions in East Punjab and three in Jammu and Kashmir.

Whether this bold maneuver would ever have succeeded will never be known because it ended in ignominy, even though Pakistan had much superior weaponry, including the US-supplied Patton tank. It failed for three reasons:

- Sheer incompetence. In the beginning, a Patton flipped over a bridge, created a log-jam and slowed the advance.

- Poor intelligence about the terrain on the Indian side of the border. The Pattons lost the momentum when the Indians breached a levee, flooding the sugar field they were traversing.

- Lack of amour-infantry coordination. This allowed Indian jeeps mounted with recoilless rifles to pick off the mired-in-mud Pattons one by one.

Afterwards, Naseer told another divisional commander that he wanted to shoot himself. When the news got to the field marshal, he said it would have been nice if Naseer had indeed done so.

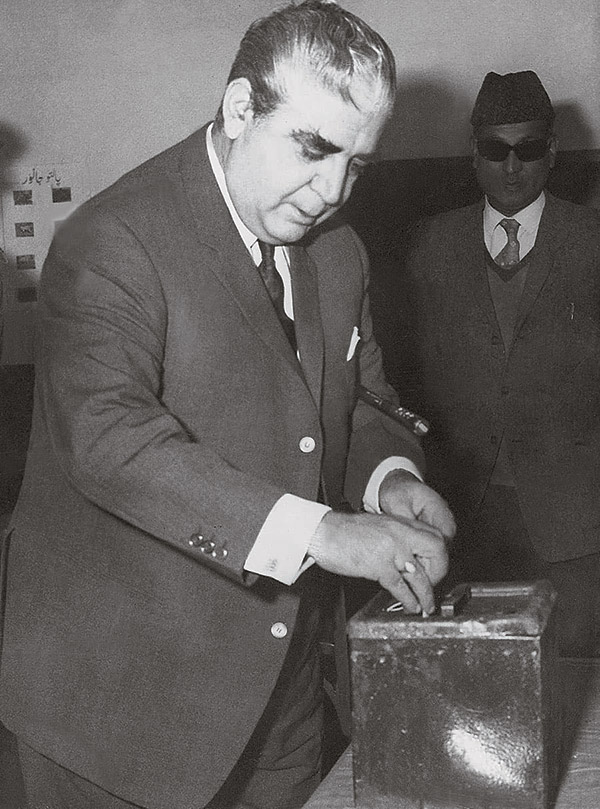

Ayub had gradually built up the Pakistani military since taking over as the army chief in 1951. He had succeeded in equipping the military with modern weaponry from the United States, much of it acquired at below-market price and financed with American aid. Indeed, as Gohar tells us, two dozen B-57Bs bombers were provided free of charge. It pained Ayub greatly to see all this go to waste in the war with India, especially when he had emerged victorious in the national elections against Fatima Jinnah.

Gohar implies that Ayub had concluded that the war was a disaster for Pakistan, being based on unfounded assumptions about a Kashmiri uprising and about India sitting still on the international border. But, like a true son, Gohar does not put the blame on his father.

Instead, he points the finger at Ayub’s foreign minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, and the divisional commander in Kashmir. He says Ayub wanted the army to conduct an inquiry into the war. But it was never held because Yahya, then army chief, did not want it done.

Gohar concedes that the celebration of Ayub’s Decade of Development was ill-conceived but places the blame for its observance on the shoulders of the information secretary, Altaf Gauhar. Once again he is absolving his father.

As the Ayubian denouement neared its end, people rioted. Gohar tells us that an advisor suggested that Ayub should kill 5,000 people to restore the writ of the state. However, Ayub replied that he could not even kill 50 chicken, let alone 5,000 people. He added, were he to begin killing people just to stay in power, four times that number would come after him to take revenge.

The fact that Pakistan was not turned into a killing filed on Ayub’s watch speaks of his sagacity and compassion. However, the fact that Ayub had appointed Yahya the army chief a few years earlier spoke poorly of his ability to pick lieutenants.

As events got out of control in East Pakistan in 1971, Ayub counseled Yahya through a back channel that he should negotiate a withdrawal of Pakistani forces with Shaikh Mujib (then Yahya’s prisoner) and convert Pakistan into a confederation. He had rightly concluded that after the army action, it could not survive as a federation.

But Yahya was not in the mood to listen to anyone, least of all to his former mentor. As so often happens in history, when the inevitable happened, Yahya blamed the defeat of the army he commanded on the “treachery of the Indians.” That statement stands out for its originality. There are few instances in history where a defeated general blames his defeat on his enemies. As far as we know, Napoleon did not put the blame for his defeat at Waterloo on the Duke of Wellington.