There were two overriding factors why the ban came into effect. According to Iqbal Haider Butt’s book, Revisiting Student Politics in Pakistan, the results of the 1983 student union elections in Karachi in which anti-Zia student alliances had swept the polls, set off alarm bells in the regime.

Student outfits had played a major role during the 1968 protest movement against the Ayub Khan regime (1958-69). It had forced him to resign in March 1969. In late 1983, Sindh’s provincial set-up superintended by Lieutenant-General SM Abbasi warned the Zia dictatorship that Sindh’s universities and colleges can once again become hotbeds of anti-government agitation. This concern influenced the dictatorship to impose a ban on politics and on student union elections in all state-owned universities and colleges.

The Martial Law authorities claimed that this was being done to curb incidents of violence on campuses, mostly during student union elections. It is true that violence between student outfits and police and between student organizations themselves had witnessed a manifold increase, but this increase largely came after Zia had imposed the country’s third martial law through a reactionary military coup in July 1977.

The ban was vehemently opposed by student activists who took to the streets in Karachi and Lahore, attacking police personnel and setting fire to dozens of buses. The protests were led by the Islami Jamiat Taleba (IJT), the student-wing of the Jamat-i-Islami (JI). The JI had supported the toppling of the ZA Bhutto regime by Zia in 1977 and was supporting the regime’s policy of training, financing and harboring Afghan insurgents (the mujahedeen) against the Soviet-backed government in Kabul.

Butt informs that during the anti-ban protests, Zia asked JI to rein-in its student-wing, which it eventually did. But it wasn’t easy. The wedge between JI and Zia had already been increasing so it took some coaxing by senior JI members to make IJT withdraw from the protest.

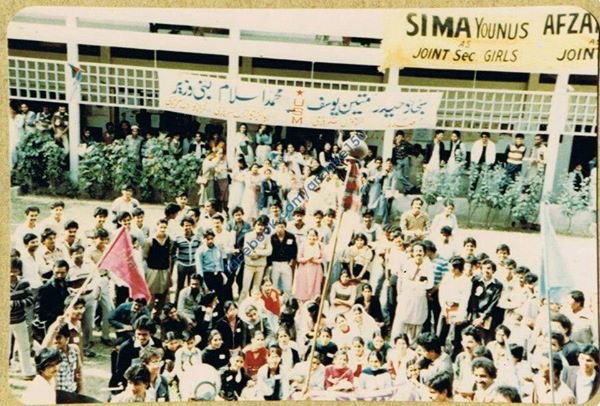

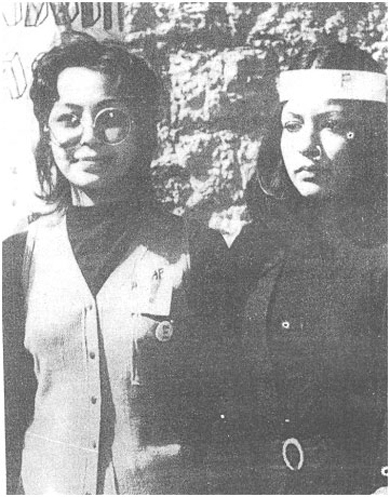

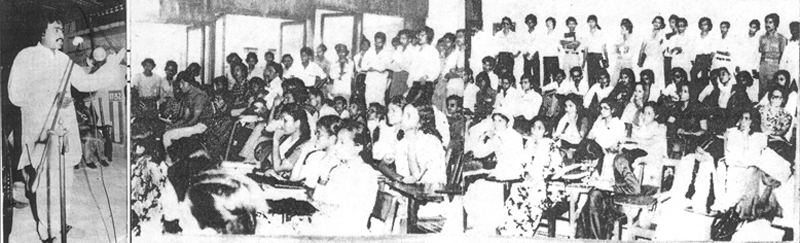

The progressive students’ alliance, the United Students Movement (USM) holding a rally during the 1983 student union elections at the Karachi University.

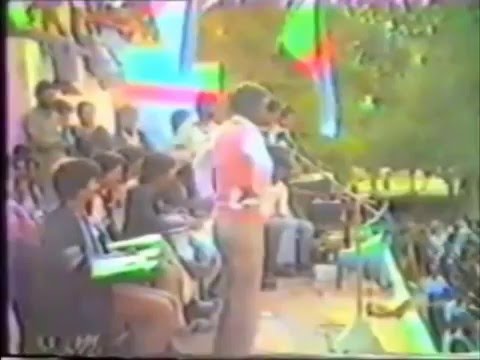

The NSF-led alliance celebrating victory in the 1983 student union elections at Karachi’s Dow Medical College.

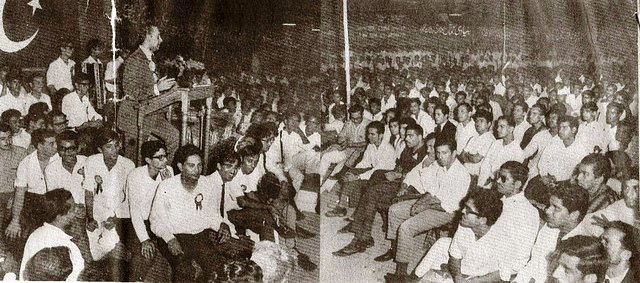

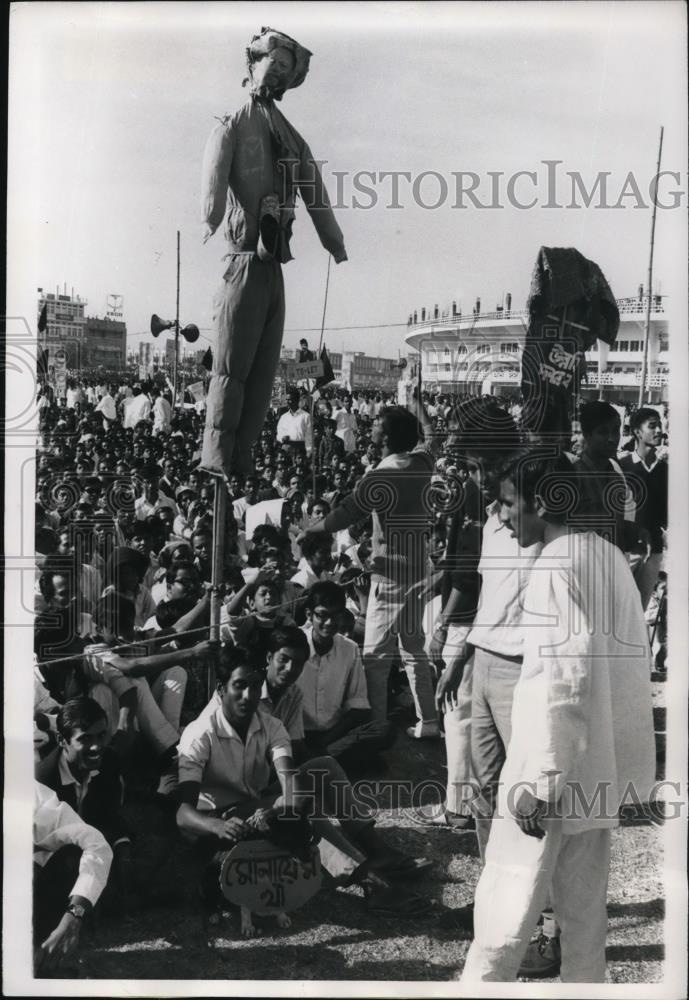

The IJT holding a protest rally against the ban on student unions in 1984.

The second overriding reason behind the ban had to do with the steady decline of student activism around the world. Student politics and activism had witnessed a peak globally in the 1960s. But this peak had begun receding from the mid-1970s onward. In his 2010 book, Blood & Rage, Michael Burleigh wrote that one of the reasons behind the rise of student activism in the 1960s was that a large number of middle and lower-middle-class men and women had begun to enroll in colleges and universities after the end of Second World War.

According to Burleigh, even though most European countries, the United States and many new post-colonial realms in Asia and Africa enjoyed economic booms of one kind or the other after the War (especially in the 1960s), their colleges and universities were not able to accommodate such a large influx of new students. This created numerous logistical and administrative problems and left the students feeling disgruntled and angry.

In 1950, a group of students at Karachi’s Dow Medical College formed an outfit which was to work as a pressure group to persuade the government to improve the conditions of Pakistan’s colleges and universities. The outfit called itself the Democratic Students Federation (DSF).

Burleigh wrote that many students channeled this anger and feelings of disaffection through radical political ideologies, mainly those of the left. Take for instance the first major exhibition of student activism in Pakistan. The many infrastructural and logistical problems the newly formed country faced after its inception in August 1947 were also reflected in the state of the universities and colleges that Pakistan inherited.

In 1950, a group of students at Karachi’s Dow Medical College formed an outfit which was to work as a pressure group to persuade the government to improve the conditions of Pakistan’s colleges and universities. The outfit called itself the Democratic Students Federation (DSF). By 1953 DSF had established itself in other colleges of Karachi and also in a few colleges in Lahore and Rawalpindi. The same year DSF drew a ‘charter of demands.’ It demanded that the government address issues related to tuition fees and the condition of the classrooms. It also demanded the creation of a university in Karachi.

This was followed by a ‘Demands’ Day Rally’ in Karachi. But the rally was attacked by the police. The commotion caused the death of six students. Even though the government finally agreed to build a university in Karachi, it accused DSF of being manipulated and influenced by the Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP). In 1954, both CPP and DSF were banned.

A DSF leader addressing a protest rally in Karachi in 1953.

Police open fire at a DSF rally in Karachi (1953).

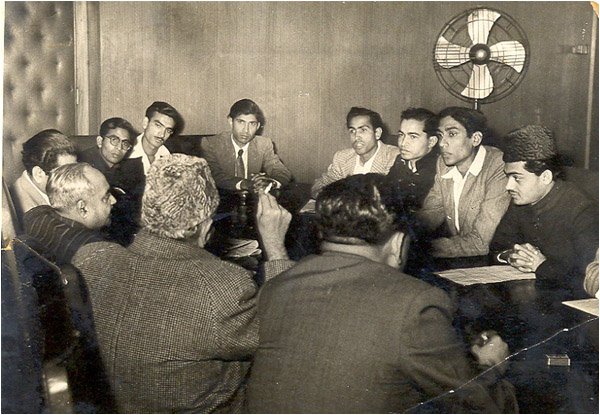

DSF members meet government officials in 1953 and demand the construction of a new university in Karachi. The government agreed, but soon banned DSF.

In 2009 I interviewed (for Dawn) one of DSF’s founders, the late Dr Mohammad Sarwar. He said DSF was not a ‘front organization’ of the CPP nor was it its student-wing. Dr Sarwar added that DSF purely came into being to attract the attention of the government towards the many problems the students were facing in Pakistan.

DSF managed to become one of the largest student outfits in Sindh and Punjab. Others included the two factions of the Muslim Students Federation (MSF). MSF was the student-wing of Pakistan’s founding party, the All India Muslim League. But the party had splintered after Pakistan’s creation and so had its student outfit.

S Zia Abbas in his 1970 book, Students and the Nation, wrote that in an attempt to neutralize DSF’s influence, the government facilitated the formation of the National Students Federation (NSF) in 1955. It was a small youth outfit based in Karachi. According to Abbas, in 1956, NSF was ‘infiltrated’ by some former DSF members and young Marxist radicals. Its disposition was radically changed when the outfit was led to take part in an anti-Israel and anti-British rally during the Suez Crisis in Egypt.

By 1958, NSF had begun to win student union elections in collages of Karachi, Lahore and Rawalpindi. In 1959, alarmed by the rise of leftist sentiments on campuses and the NSF, the JI allowed its student-wing, the IJT, to begin taking part in student politics.

NSF and IJT became the country’s two leading student parties (in West Pakistan). NSF held sway in most colleges in Sindh and Punjab, whereas the IJT dug in its heels in Lahore’s Punjab University and the newly-built Karachi University. The East Pakistan Students League (EPSL), the student-wing of the Bengali nationalist party, Awami League (AL), emerged as the largest student outfit in East Pakistan.

In Karachi, the IJT also came to express the disillusionment of young Urdu-speaking Karachiites (Mohajirs) who felt that the Ayub regime was ousting the Mohajirs from the bureaucracy and the overall economy. In 1962 NSF linked up with the left-wing National Awami Party (NAP) which was an amalgamation of progressive Sindhi, Pashtun, Baloch and Bengali nationalists.

In the student union elections between 1960 and 1967, the pendulum continued to swing between NSF and IJT.

In 1965-66 when the Ayub regime began its slow decline, NSF aligned itself with Ayub’s renegade young foreign minister, ZA Bhutto, who was dismissed by Ayub in early 1966.

In 1967 NSF broke into two factions. This was triggered by the splintering of NAP into a pro-China group (NAP-Bhashani) and a pro-Soviet faction (NAP-Wali).

Students gather to vote during the 1964 student union elections at a college in Karachi.

ZA Bhutto addressing an NSF gathering in 1967.

A large segment of the pro-China (or Maoist) factions of NSF allied with Bhutto’s newly formed Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), whereas the pro-Soviet faction became associated with NAP-Wali.

NSF in West Pakistan and EPSL in East Pakistan were on the forefront during the 1968 uprising against the Ayub regime. 1968 was a significant year for student politics around the world. Mark Boren in his 2013 tome Student Resistance: History of an Unruly Subject wrote that in 1968 student uprisings erupted simultaneously in over a dozen countries in Europe, the United States, Africa and Asia.

According to Burleigh the reasons for this were rather paradoxical. Booming economies had rapidly facilitated the expansion of the urban middle-classes. But the boom could not accommodate the class bulge that it had created, thus politically and socially isolating many members of the expanding classes. The anger at this was expressed by the students who sought to address their predicament through various forms of leftist ideas and ideologies.

Ayub was forced to resign in 1969 and in 1970 the country’s first general election based on adult franchise was held. PPP and NAP scored big in West Pakistan whereas AL swept East Pakistan. In December 1971 a vicious civil war in East Pakistan saw it break away to become Bangladesh. ZA Bhutto and his PPP came to power in West Pakistan.

After reaching a peak in Europe and the US in 1968, student politics began to disintegrate. The post-1973 Oil Crisis, which saw many western economies implode, shrank the space for students to be able to indulge in activism as well as manage to survive for long periods without being associated with any direct economic activity. This became almost impossible to do.

The receding of the activism wave caused frustration in various student outfits. They mutated and became anarchic armed organizations. Militant left-wing groups such as Italy’s Red Brigade, Germany’s Red Army Faction, Japan’s Red Army, France’s Action Directe, Britain’s Angry Brigade and North America’s Weather Underground all emerged from the fractured student outfits of the late 1960s.

Student-wing of the Awami League, the EPSF, protesting against the Ayub regime in 1968 at the Dhakka University.

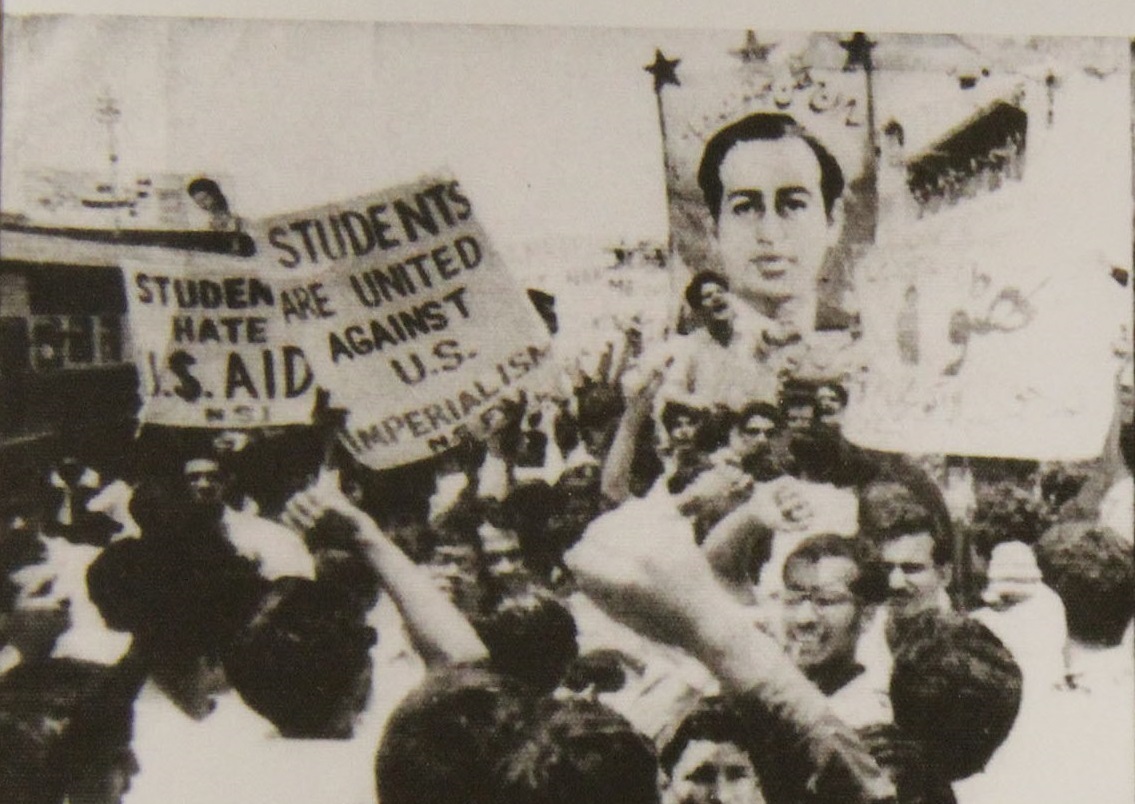

NSF taking out a pro-Bhutto rally during the b1968 anti-Ayub protest movement.

In 1968, student protests erupted in over a dozen countries across Asia, Europe, South America, Africa and the United States.

Conscious of the volatile nature of student politics which he had witnessed (and utilized) to his advantage in the late 1960s, Prime Minister Bhutto decided to streamline it through an ordinance. In 1974 the government promulgated the Students Union Ordinance according to which state-owned universities and colleges were to hold annual student union elections on dates provided by the government.

So it is rather remarkable that when student politics was falling away in most other countries, it settled down quite well in Pakistan and developed a notable democratic culture in higher educational institutions.

Student union elections were held regularly and in an amicable manner between 1971 and 1977. The competition was mainly between IJT and progressive student alliances, mostly made up of NSF factions; and the student-wing of the PPP (PSF) and ethnic student groups such as the Baloch BSO, the Pashtun PkSF and the Sindhi JSSF. The student-wing of the Barelvi JUP, the ATI, was also active.

But things changed after the 1977 coup. The Zia regime instinctively went after the ‘progressive’ groups. For a while IJT got a free hand and by 1979 it had begun to arm itself. The ‘weaponization’ of student outfits gained pace. Pakistan’s involvement in the Afghan civil war saw the proliferation of guns. There were four deaths due to campus clashes between 1971 and 1977. But the number of deaths rose dramatically to over two dozen between 1980 and 1983.

Student politics in most western countries fractured in the 1970s and gave birth to various left-wing militant outfits.

NSF supporters at the 1972 student union elections at Karachi University.

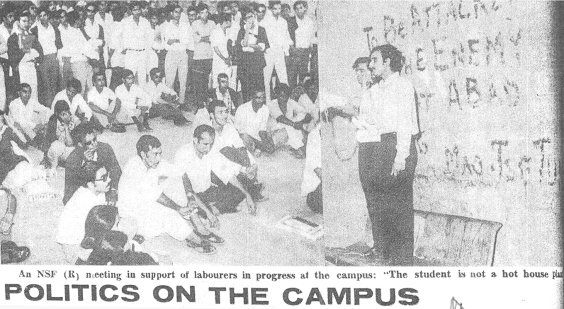

An NSF faction holding a corner meeting at the 1973 student union elections at Lahore’s Punjab University.

The Mohajir nationalist students outfit, the APMSO, is formed in 1978.

IJT campaigning for the 1979 student union elections.

The first Benazir Bhutto regime lifted the ban on student unions in 1989. Union elections were held in all state-owned collages of Punjab. But in 1992, on the insistence of the first Nawaz Sharif regime, the Supreme Court imposed a blanket ban on student politics. The ban came on the heels of deadly clashes between PSF and APMSO (the student-wing of MQM) in Karachi and MSF and IJT in Lahore.

Conventional student politics began to rapidly wither away. Student politics of this nature was a Cold War phenomenon. In Pakistan, the increasing demand for privately-owned colleges and universities and a significant decrease in the standards and value of state-owned educational institutions, also contributed to the decline.

Nevertheless, even though private colleges and universities did not allow any form of organized student politics, new groups were allowed to enter. These groups did not operate like the conventional student political outfits. In fact they claimed to shun politics and pretended to help the students become ‘better Muslims.’ They claimed to be evangelical in nature.

The so-called evangelical outfits slipped into private educational institutions with a more social agenda. Instead of preaching political ideology, these groups emphasized ‘good social behavior’.

But when incidents of terrorism involving educated middle-class youth saw an increase from 2013 onwards, many observers claimed that this was due to many private educational institutions allowing so-called evangelical groups to operate on their campuses and which led to some young men eventually join more hardcore militant outfits. Those now lobbying to revive conventional student politics claim that such a revival can neutralize the radicalization of alienated middle-class youth.

Notable Student Organizations of Pakistan

Democratic Students Federation (DSF)

Formed: 1950. Banned: 1954; Reformed: 1977.

Ideology: Marxist.

Affiliation: Communist Party of Pakistan (1950-54).

Militant Wing: Red Guards (Defunct).

Factions: None.

Peak Period: 1950-54

Current Status: Defunct.

Muslim Students Federation (MSF)

Formed: 1937

Ideology: Muslim Nationalism (1937-66); Centre-Right (1970s); Islamist (1985-97); Centrist (2001 – Present).

Affiliations: All India Muslim League (1937-47); Muslim League (1948-68); Functional Muslim League (1970s); Pakistan Muslim League (1985-92); Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (1993-2002); Pakistan Muslim League-Quaid (2002-2007); PML-N (2008- Present).

Militant Wing: None (but MSF was involved in an armed tussle with IJT in the early 1990s).

Peak Period: 1937-1948; 1990-98.

Factions: Jinnah Muslim Students Federation (1949-56).

Current Status: Active

National Students Federation (NSF)

Formed: 1955

Ideology: Socialist/Progressive.

Affiliations: National Awami Party (19560-67); Pakistan People’s Party (1967-72); Mazdoor Kissan Party (1974-80); Awami Workers Party (2012-Present)

Militant Wing: Mazdoor Kissan Party (Defunct)

Peak Period: 1960-1973

Factions: NSF-Rashid (Defunct); NSF-Kazmi (Defunct); NSF-Bari (Defunct); NSF-Miraj (Defunct); Sindh NSF (Defunct)

Current Status: Partially active

Islami Jamiat Taleba (IJT)

Formed: 1947

Ideology: Political Islam

Affiliations: Jamat-i-Islami

Militant Wing: Thunder Squad (Defunct); Allah Tigers (Defunct)

Peak Period: 1969-81

Factions: Pasban (1992)

Current Status: Active

Peoples Students Federation (PSF)

Formed: 1972

Ideology: Left-Liberal/Progressive

Affiliations: Pakistan People’s Party

Militant Wing: PSF-Tipu (Defunct)

Peak Period: 1976-96

Factions: PSF-Shaheed Bhutto

Current Status: Active

Anjuman Taleba Islam (ATI)

Formed: 1969

Ideology: Islamic (Sunni Barelvi)

Affiliations: Jamiat Ulema Pakistan (1969-85); Tehreek-i-Labaik Pakistan

Militant Wing: None

Peak Period: 1974-85

Factions: None

Current Status: Active

Insaf Students Federation (ISF)

Formed: 1997

Ideology: Centre-Right

Affiliations: Pakistan Tehreeki-Insaf

Militant Wing: None

Peak Period: 2011-2017

Factions: None

Current Status: Active

Imamia Students Organization (ISO)

Formed: 1972

Ideology: Islamic (Shia Muslim)

Affiliations: Tehreek-i-Nifaz-i-Fiqa Jaffria (1974-2002); Majlas-i-Whahadat-i-Muslameen

Militant Wing: None

Peak Period: 1980-99

Factions: None

Current Status: Active

Baloch Students Organization (BSO)

Formed: 1968

Ideology: Bloch Nationalism/Progressive

Affiliations: National Awami Party (1968-75); Balochistan National Movmenet (1988-90); Balochistan National Party (1993 – N/A); National Party (2013).

Militant Wing: BSO-Azad; Balochistan Liberation Army; Balochistan Republican Army

Peak Period: 1969-75; 1988-91; 2003-2013

Factions: BSO-Azad; BSO-Mengal; BSO-Hayee; BSO-Nadir

Current Status: Active

All Pakistan Mohajir Students Organization (APMSO)

Formed: 1978

Ideology: Mohajir Nationalism/Progressive

Affiliations: Muttahida Qaumi Movment

Militant Wing: Black Tigers (Defunct)

Peak Period: 1988-2008

Factions: None

Current Status: Active

Pashtun Students Federation (PkSF)

Formed: 1969

Ideology: Pashtun Nationalism

Affiliations: National Awami Party (1969-77); Awami National Party

Militant Wing: None

Peak Period: 1988-1998; 2008

Factions: None

Current Status: Active

Jeeay Sindh Students Federation (JSSF)

Formed: 1973

Ideology: Sindhi Nationalism

Affiliations: Jeeay Sindh Party

Militant Wing: None (but JSSF had been involved in militancy)

Peak Period: 1974-83

Factions: Jeeay Sindh Tarakee-Pasand Students

Current Status: Partially active