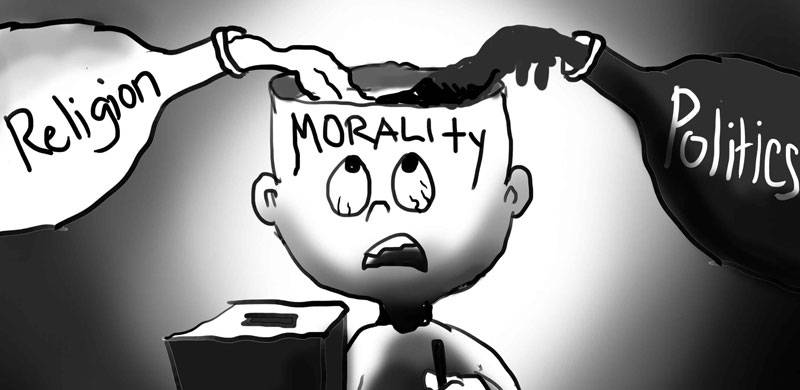

In this article, Nadeem F. Paracha explains how Dr Ramesh Kumar's resolution presented in the National Assembly to ban liquor across the country was actually an exhibition of what George Bernard Shaw termed as 'middle-class morality'

Urdu author, poet and satirist, Ibn-i-Insha, wrote that he once saw a person from the ‘respectable middle-class’ talk to a poor man at a mosque. The gentleman asked the poor man what he was praying for. The poor man said he was praying for shelter, some food and maybe even a job.

Hearing this, the gentleman got slightly stressed and asked: “Why are you praying for these materialistic things?”

The poor man replied with a question of his own: “What do you pray for, sahib?”

“I pray for the strength of my faith,” the gentleman proudly responded.

“Good,” said the poor man, “one often prays for things they do not have.”

Ibn-i-Insha was satirizing a particular mindset which has been prevalent in Pakistan’s urban middle-classes. Some call it ‘middle class morality’. In fact Insha’s tragic fate too can shed some light on this mindset.

At the peak of his career in 1974, Insha was diagnosed with cancer. Doctors in Pakistan believed that his cancer was treatable but only in a Western country.

On an appeal from Insha’s fans, the populist government of ZA Bhutto worked out an arrangement with him. Insha was to be given a salaried job in the cultural section of the Pakistan embassy in London where he could continue his career as a poet and writer and use his salary to pay for the treatment from British doctors. Insha agreed.

The treatment seemed to be working when three years later (in July 1977) Bhutto’s regime was toppled in a reactionary military coup. The military regime was headed by Gen Zia who wasn’t a fan of certain cultural activities and vocations which he believed to be ‘vulgar’.

Claiming that they were damaging Pakistan’s ‘moral fabric’, the military regime blacklisted dozens of poets, intellectuals, painters, actors and actresses. Then he ordered the termination of Insha’s employment at the embassy.

Insha’s treatment came to a halt and his condition began to deteriorate. Some friends shifted him to a public hospital where he slipped into despondency and passed away in 1978. As Zia would have it, instead of praying for money for his treatment, Insha should have prayed for his soul.

In his 1938 play Pygmalion, the Irish playwright, George Bernard Shaw, explained middle class morality as a phenomenon in which freedom is replaced by fear. Shaw was lampooning British middle class values in the first half of the 20th century.

He explained middle-class morality as one which makes a person become overtly conscious about his/her economic and social status. But this person continuously feels insecure because they fear that even a slight downward trend in their status may put them in the league of folks from the classes below. This anxiety thus drives them to stridently exhibit certain mannerisms and beliefs which they imagine are more ‘civilized’ and which distinguish them from those in the classes below.

Professor K Husain, a popular teacher at the state-owned college that I attended in Karachi in the mid-1980s, once rather splendidly explained Shaw’s observations in the context of Pakistan.

In early 1985, after the police had raided our college to apprehend certain ‘subversive elements,’ a group of students and I visited the professor’s office. He was the Dean of Commerce and we wanted him to demand the release of the apprehended students.

After he had agreed to talk to the principal of the college, we began talking politics with him. During the discussion he asked us whether any of us had read Shaw’s Pygmalion. We hadn’t. He talked briefly about it and then asked, “Do you know why Bhutto fell?” We all came up with our usual half-baked Marxist theories, until he interrupted: “Middle-class morality!”

We became silent. He smiled and continued: “Bhutto fell due to middle-class morality. His populist demeanor started to make the middle and upper classes uncomfortable. They began to feel that the classes below them were being emboldened by Bhutto. This threatened their carefully cultivated economic and social standing in society. Why else do you think the majority of people who took part in the movement against Bhutto belonged to the middle-classes?”

A student tentatively asked, “Because of his socialist policies?”

“Nonsense!” the professor shot back. “There wasn’t a single socialist bone in Bhutto. But it was the perception that he created of empowering the poor which aggravated the middle classes!”

The professor then asked us to recall the platform which Bhutto’s opponents used during their movement against him. “Morality and faith,” he answered himself.

The professor claimed that Bhutto’s opponents had little or no economic programme to speak of. He asked: “Have you ever read their manifesto [issued just before the March 1977 election]? All it says is that a theocratic state would produce a just and happy society. That’s all.”

Then the professor sniggered: “So off they went, attacking liquor stores, clubs and cinemas … as if it were these which were empowering the poor and undermining the middle-classes!”

I must add, the late professor detested Bhutto. He neither drank nor smoked. Heck, he even hated colas. But his words continue to echo in my head every time anyone (from the government or media) suddenly decides to crib about certain activities which they deem immoral or are against the grain of ‘our culture’.

Take for instance the gentlemen who in 2016 submitted a petition at the Sindh High Court against liquor stores in Karachi. Alcohol was banned (for Muslims) in Pakistan in April 1977. The stores are there for non-Muslims, but, of course, many Muslims too manage to buy from there.

Question is, how much have these sinister stores contributed to whatever that has gone wrong in Pakistan ever since 1977? Do these stores produce terrorists and extremists? Are they to be blamed for the country’s on-going economic crisis? Truth is, curbs on alcohol have actually yielded mafias which produce dangerous and tainted alcoholic beverages (katchi sharaab).

Even though the high court entertained their petition, a three-member Supreme Court bench headed by the Chief Justice of Pakistan Saqib Nasir set aside the high court ruling after noting that closing down wine shops on the basis of morality was not the job of the courts.

A friend recently quipped: “Ask a nazim or an MPA to give you water, electricity or a road, and he’ll tell you that he will gift you with something more noble: a ban on what he deems immoral. Easier done. Silly priorities. Us middle-class folk will remain numb about issues such as terrorism and domestic violence, but applaud initiatives which make us feel morally superior.”

My good professor, God bless him, also came to mind when in 2017 a PTI MPA from Karachi and a petty government bureaucrat in Sindh had a problem with schools teaching dance to children. This is an example of idle minds trying to exercise middle-class morality to justify their otherwise feeble political status.

And what about Jamshed Dasti, the former MPA from Muzaffargarh who once raised such a huge hue and cry after allegedly discovering empty whisky bottles outside the parliamentary lodges in Islamabad? Or an unelected Hindu MNA, Ramesh Kumar, who recently assumed that he was speaking for all the Hindu, Christian, Sikh and Zoroastrians of the country by suggesting that “all faiths are against alcohol” and that there should be a “blanket ban on it?” Some went on to call him suffering from the Stockholm Syndrome.

But in the context of my professor’s theory, Dasti and Kumar’s cases become rather interesting. Dasti originally comes from a working-class background, and Kumar is a member of the minority Hindu community. Becoming MNAs created a perception in their mind that they were now from the ‘morally superior’ class. They were thus obliged to exhibit some middle-class morality, especially after they felt that their status was being relegated to that of being token MNAs.

In 1993 during a seminar on ‘youth and crime’ held by a large media group in Karachi, a working-class lad in the audience complained that his sisters were being harassed on the streets in his locality and the police refused to do anything about it.

A middle-aged shurfa class member of the panel matter-of-factly replied, “Son, I am assuming your sisters do not wear hijabs?”

Go figure.

Urdu author, poet and satirist, Ibn-i-Insha, wrote that he once saw a person from the ‘respectable middle-class’ talk to a poor man at a mosque. The gentleman asked the poor man what he was praying for. The poor man said he was praying for shelter, some food and maybe even a job.

Hearing this, the gentleman got slightly stressed and asked: “Why are you praying for these materialistic things?”

The poor man replied with a question of his own: “What do you pray for, sahib?”

“I pray for the strength of my faith,” the gentleman proudly responded.

“Good,” said the poor man, “one often prays for things they do not have.”

Ibn-i-Insha was satirizing a particular mindset which has been prevalent in Pakistan’s urban middle-classes. Some call it ‘middle class morality’. In fact Insha’s tragic fate too can shed some light on this mindset.

At the peak of his career in 1974, Insha was diagnosed with cancer. Doctors in Pakistan believed that his cancer was treatable but only in a Western country.

On an appeal from Insha’s fans, the populist government of ZA Bhutto worked out an arrangement with him. Insha was to be given a salaried job in the cultural section of the Pakistan embassy in London where he could continue his career as a poet and writer and use his salary to pay for the treatment from British doctors. Insha agreed.

The treatment seemed to be working when three years later (in July 1977) Bhutto’s regime was toppled in a reactionary military coup. The military regime was headed by Gen Zia who wasn’t a fan of certain cultural activities and vocations which he believed to be ‘vulgar’.

Claiming that they were damaging Pakistan’s ‘moral fabric’, the military regime blacklisted dozens of poets, intellectuals, painters, actors and actresses. Then he ordered the termination of Insha’s employment at the embassy.

Insha’s treatment came to a halt and his condition began to deteriorate. Some friends shifted him to a public hospital where he slipped into despondency and passed away in 1978. As Zia would have it, instead of praying for money for his treatment, Insha should have prayed for his soul.

Ibn-e-Insha (left) being interviewed by Zia Mohyeddin on Radio Pakistan.

In his 1938 play Pygmalion, the Irish playwright, George Bernard Shaw, explained middle class morality as a phenomenon in which freedom is replaced by fear. Shaw was lampooning British middle class values in the first half of the 20th century.

He explained middle-class morality as one which makes a person become overtly conscious about his/her economic and social status. But this person continuously feels insecure because they fear that even a slight downward trend in their status may put them in the league of folks from the classes below. This anxiety thus drives them to stridently exhibit certain mannerisms and beliefs which they imagine are more ‘civilized’ and which distinguish them from those in the classes below.

Professor K Husain, a popular teacher at the state-owned college that I attended in Karachi in the mid-1980s, once rather splendidly explained Shaw’s observations in the context of Pakistan.

In early 1985, after the police had raided our college to apprehend certain ‘subversive elements,’ a group of students and I visited the professor’s office. He was the Dean of Commerce and we wanted him to demand the release of the apprehended students.

After he had agreed to talk to the principal of the college, we began talking politics with him. During the discussion he asked us whether any of us had read Shaw’s Pygmalion. We hadn’t. He talked briefly about it and then asked, “Do you know why Bhutto fell?” We all came up with our usual half-baked Marxist theories, until he interrupted: “Middle-class morality!”

We became silent. He smiled and continued: “Bhutto fell due to middle-class morality. His populist demeanor started to make the middle and upper classes uncomfortable. They began to feel that the classes below them were being emboldened by Bhutto. This threatened their carefully cultivated economic and social standing in society. Why else do you think the majority of people who took part in the movement against Bhutto belonged to the middle-classes?”

A student tentatively asked, “Because of his socialist policies?”

“Nonsense!” the professor shot back. “There wasn’t a single socialist bone in Bhutto. But it was the perception that he created of empowering the poor which aggravated the middle classes!”

The professor then asked us to recall the platform which Bhutto’s opponents used during their movement against him. “Morality and faith,” he answered himself.

The professor claimed that Bhutto’s opponents had little or no economic programme to speak of. He asked: “Have you ever read their manifesto [issued just before the March 1977 election]? All it says is that a theocratic state would produce a just and happy society. That’s all.”

Then the professor sniggered: “So off they went, attacking liquor stores, clubs and cinemas … as if it were these which were empowering the poor and undermining the middle-classes!”

I must add, the late professor detested Bhutto. He neither drank nor smoked. Heck, he even hated colas. But his words continue to echo in my head every time anyone (from the government or media) suddenly decides to crib about certain activities which they deem immoral or are against the grain of ‘our culture’.

Poster of the film adaptation of Shaw’s Pygmalion.

Take for instance the gentlemen who in 2016 submitted a petition at the Sindh High Court against liquor stores in Karachi. Alcohol was banned (for Muslims) in Pakistan in April 1977. The stores are there for non-Muslims, but, of course, many Muslims too manage to buy from there.

Question is, how much have these sinister stores contributed to whatever that has gone wrong in Pakistan ever since 1977? Do these stores produce terrorists and extremists? Are they to be blamed for the country’s on-going economic crisis? Truth is, curbs on alcohol have actually yielded mafias which produce dangerous and tainted alcoholic beverages (katchi sharaab).

Even though the high court entertained their petition, a three-member Supreme Court bench headed by the Chief Justice of Pakistan Saqib Nasir set aside the high court ruling after noting that closing down wine shops on the basis of morality was not the job of the courts.

A friend recently quipped: “Ask a nazim or an MPA to give you water, electricity or a road, and he’ll tell you that he will gift you with something more noble: a ban on what he deems immoral. Easier done. Silly priorities. Us middle-class folk will remain numb about issues such as terrorism and domestic violence, but applaud initiatives which make us feel morally superior.”

My good professor, God bless him, also came to mind when in 2017 a PTI MPA from Karachi and a petty government bureaucrat in Sindh had a problem with schools teaching dance to children. This is an example of idle minds trying to exercise middle-class morality to justify their otherwise feeble political status.

And what about Jamshed Dasti, the former MPA from Muzaffargarh who once raised such a huge hue and cry after allegedly discovering empty whisky bottles outside the parliamentary lodges in Islamabad? Or an unelected Hindu MNA, Ramesh Kumar, who recently assumed that he was speaking for all the Hindu, Christian, Sikh and Zoroastrians of the country by suggesting that “all faiths are against alcohol” and that there should be a “blanket ban on it?” Some went on to call him suffering from the Stockholm Syndrome.

But in the context of my professor’s theory, Dasti and Kumar’s cases become rather interesting. Dasti originally comes from a working-class background, and Kumar is a member of the minority Hindu community. Becoming MNAs created a perception in their mind that they were now from the ‘morally superior’ class. They were thus obliged to exhibit some middle-class morality, especially after they felt that their status was being relegated to that of being token MNAs.

In 1993 during a seminar on ‘youth and crime’ held by a large media group in Karachi, a working-class lad in the audience complained that his sisters were being harassed on the streets in his locality and the police refused to do anything about it.

A middle-aged shurfa class member of the panel matter-of-factly replied, “Son, I am assuming your sisters do not wear hijabs?”

Go figure.