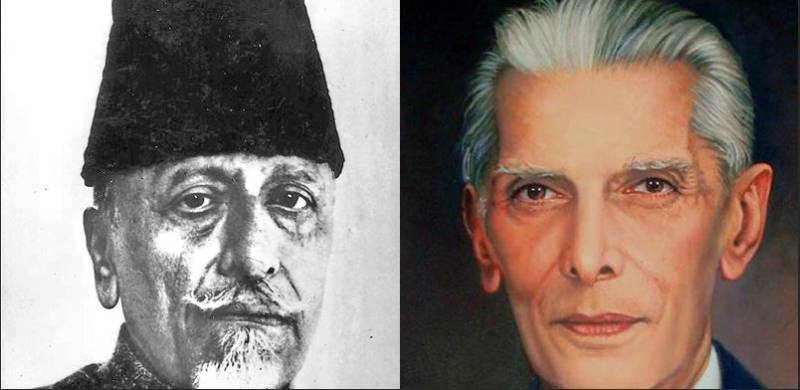

The ratio of the people who think Maulana Abul Kalam Azad was right in opposing the creation of Pakistan and those who think Jinnah was right in asking for it is probably the same. If there were no Pakistan, there’d be no way to know whether there would be more chances of communalism in India or not. Pakistan is a reality, albeit a scary one, but it is how it is now.

Otherwise, Maulana Abul Kalam was right. He was a visionary. Not just in the case of Muslims of subcontinent but also in the case of the future of Islam. His analysis of history of Islam is also very insightful and neutral. Although his opinion looks like calling for Ummah’s unity but I guess it’s more of a worrying sign about the rights of a Muslim minority, a minority which would shrunk even more in the case of partition. So was Jinnah’s vision who thought this minority should become a majority in autonomous states (remember he never asked for a separate country, neither was it a demand in Allahabad resolution nor an agreed upon decision in Cabinet Mission). He feared that without constitutional protections, Muslims would face the backlash of all the historical enmity and animosity of the Hindu majority.

However, Jinnah did rule out the fact that all Muslims could not move to the newly founded country (when he accepted the proposal of Pakistan) and how the stark cultural differences and economic concerns, transportation and communication would be major hurdles in welcoming Muslim immigrants to the Muslim majority areas (case of present-day Sindh with Mohajirs). This was a miscalculation at his end.

The concerns of both Maulana and Jinnah were more about Muslims as minority population than Islam as a unifying religion. Hence, it was an equally risky gamble on the part of both of them. If they remained a minority, there was no guarantee they wouldn’t have faced the ‘tyranny of majority’ and if they separated, there was no guarantee they would still be united. I agree this all looks like stemming from the fallacious assumption of considering Muslims as one nation, in which Maulana also believed subconsciously.

Both Maulana and Jinnah had contradictions in their demeanour, though it might be confusing to their followers, which is evident from the fact that Muslims from wide a range of political and religious spectrums followed both. There were liberals, leftists, nationalists and religious groups following each of them; and this points towards how culturally diverse this minority was. The contradiction mentioned above is quite obvious though. Maulana was a religious scholar attached to a secular Congress while Jinnah was a liberal/secular person attached to a communal Muslim League. Therefore, their political motives were either shady or highly contradictory. You cannot play both sides at the same time. Only if they had switched places, it would’ve made more sense and would’ve made a more logically straight story for Muslims of subcontinent to understand and follow.

One would rather ask what might have been a solution to this uncertainty of the future of Muslim population in India, if not partition. The solution was complete secularisation of the state. However, it was as hard to achieve in a united India then as it is harder to achieve in both countries now.

Regardless, Pakistan is a reality now and it should be accepted de facto. We can study history and offer more insights on the role of these leaders but taking sides, or brushing someone with broad strokes of criticism won’t be fruitful. They were also human beings in a complicated situation with complicated ideals and were unable to predict precise dynamics of a complicated and historically intertwined cultures (not just religions). I think if we work on these safe assumptions, only then can we logically comprehend the present situation and work towards realistic goals of possible and practical outcomes.

Otherwise, Maulana Abul Kalam was right. He was a visionary. Not just in the case of Muslims of subcontinent but also in the case of the future of Islam. His analysis of history of Islam is also very insightful and neutral. Although his opinion looks like calling for Ummah’s unity but I guess it’s more of a worrying sign about the rights of a Muslim minority, a minority which would shrunk even more in the case of partition. So was Jinnah’s vision who thought this minority should become a majority in autonomous states (remember he never asked for a separate country, neither was it a demand in Allahabad resolution nor an agreed upon decision in Cabinet Mission). He feared that without constitutional protections, Muslims would face the backlash of all the historical enmity and animosity of the Hindu majority.

However, Jinnah did rule out the fact that all Muslims could not move to the newly founded country (when he accepted the proposal of Pakistan) and how the stark cultural differences and economic concerns, transportation and communication would be major hurdles in welcoming Muslim immigrants to the Muslim majority areas (case of present-day Sindh with Mohajirs). This was a miscalculation at his end.

The concerns of both Maulana and Jinnah were more about Muslims as minority population than Islam as a unifying religion. Hence, it was an equally risky gamble on the part of both of them. If they remained a minority, there was no guarantee they wouldn’t have faced the ‘tyranny of majority’ and if they separated, there was no guarantee they would still be united. I agree this all looks like stemming from the fallacious assumption of considering Muslims as one nation, in which Maulana also believed subconsciously.

Both Maulana and Jinnah had contradictions in their demeanour, though it might be confusing to their followers, which is evident from the fact that Muslims from wide a range of political and religious spectrums followed both. There were liberals, leftists, nationalists and religious groups following each of them; and this points towards how culturally diverse this minority was. The contradiction mentioned above is quite obvious though. Maulana was a religious scholar attached to a secular Congress while Jinnah was a liberal/secular person attached to a communal Muslim League. Therefore, their political motives were either shady or highly contradictory. You cannot play both sides at the same time. Only if they had switched places, it would’ve made more sense and would’ve made a more logically straight story for Muslims of subcontinent to understand and follow.

One would rather ask what might have been a solution to this uncertainty of the future of Muslim population in India, if not partition. The solution was complete secularisation of the state. However, it was as hard to achieve in a united India then as it is harder to achieve in both countries now.

Regardless, Pakistan is a reality now and it should be accepted de facto. We can study history and offer more insights on the role of these leaders but taking sides, or brushing someone with broad strokes of criticism won’t be fruitful. They were also human beings in a complicated situation with complicated ideals and were unable to predict precise dynamics of a complicated and historically intertwined cultures (not just religions). I think if we work on these safe assumptions, only then can we logically comprehend the present situation and work towards realistic goals of possible and practical outcomes.