Recently, I was a silent observer of a discussion between two ladies on the state of the Urdu language in Pakistan.

“I don’t know why children have to study Urdu in school, it’s so useless,” said one lady. “ I cannot read or write in Urdu, and it doesn’t get in the way at all,” she continued with pride. “But Urdu is our national language, it is an integral part of our identity,” retorted the other lady rambunctiously, “we should stop pretending to be desi goras; Pakistan was made to rid us of this insecurity and the Urdu language gives us pride in our identity.”

Like most graduates of the Cambridge system, both of them had studied English as a first language and Urdu as a second language, and this discourse represents the ambivalence one constantly observes regarding Urdu and its place in our society.

In 1948, Muhammad Ali Jinnah declared Urdu to be the national language of Pakistan despite the country having a diverse litany of cultures and their corresponding languages. The rationale was to use the Urdu language as an adhesive to unite the nation, but this came at the cost of disenfranchising the East Pakistanis who comprised over 50% of the population of Pakistan. The Bengalis took pride in their language and they had good reason to: historical Bengali has a rich literary and cultural legacy. After all, it was the great Bengali writer Rabindarnath Tagore who became the first South Asian to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Hence, the Bengali Language Movement was an inevitability that eventually succeeded in making Bengali, along with Urdu, the national language of Pakistan. However, this linguistic fissure had sowed the seeds that would culminate in a horrific war of independence years later and reap the new state of Bangladesh carved out of the Eastern wing of Pakistan.

Ever since humans began using language to communicate and cooperate with each other, it has become a central tenet of their culture and in essence a keeper of their thoughts and ideas propelled through generations in the form of stories and folktales. We can learn its importance from Bangladesh’s movement for independence, as it united Muslim Bengalis with their fellow non-Muslim countrymen against their predominantly Muslim co-religionists in West Pakistan – their language, the vessel of their culture, took precedence over their shared religion with West Pakistanis.

Today, more than seventy languages are spoken in Pakistan, most of them endangered, with Punjabi being the most spoken of them all. However, fewer than 10% of Pakistanis speak Urdu as their First Language, opting instead to speak their indigenous mother tongue – in fact, provinces have shown displeasure towards Urdu taking precedence over their provincial language in their local schools. Therefore, Urdu, instead of actually being a ‘national language’ that symbolizes a unified ethnic culture (like Bengali for Bangladeshis) serves as Pakistan’s lingua franca, a ‘bridge language’ if you will, that allows Pakistanis of various ethnicities to communicate with each other.

Despite the lip service apropos Urdu as a ‘language of identity’, it does not fare well in the social, professional, and academic realms. In its vernacular form, Urdu is but a shadow of its glorious literary and cultural past; the language has been poorly preserved by its keepers and there is no real body tasked with its conservation and development. As an official language i.e. language of public and private organisations, Urdu shares its space with English where the latter is clearly more ubiquitous. In this realm, the tussle between the two languages is clearly in favour of English, fluency in which opens doors that won’t budge for those only proficient in Urdu. This plays out woefully in society especially in the form of class distinctions. ‘Urdu medium’ is a term used derogatorily to insinuate a person’s ignorance and lack of education, whereas the moniker ‘Burger’ is a pejorative ascribed to the predominantly English speaking population considered to be Anglicized Pakistanis who pander to the decadent ‘Western culture.’ However, where Pakistanis' relationship with Urdu is that of ambivalence, with English it is a bittersweet one as they revere it for its socio-economic power yet abhor it for its colonial connection.

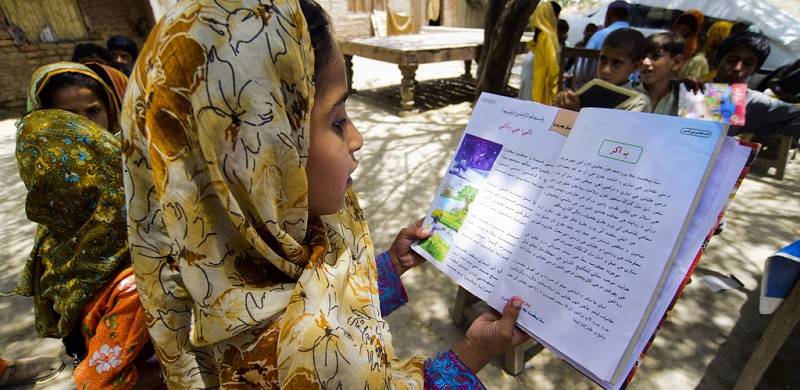

The root of the English - Urdu dichotomy rests in the disparity between the public and private education sectors. Most Pakistanis opt for the public education system i.e. the Inter/Matric system that not only suffers an outdated curriculum but also subpar administrative and pedagogical procedures. This system is considered to be more ‘urdu-medium’ and although it’s evident that English is not taught competently, even Urdu is taught without the intent of appreciating its legacy and developing it for practical use while retaining its grace. On the other hand, a few Pakistanis opt for the ‘English-medium’ Cambridge O/A Level system which is certainly more current and competent than its local counterpart, but also the more expensive option, hence afforded by a privileged few. This discrepancy plays out unequally in society and in the professional world. In my years as a corporate trainer, most of my English Language students were middle-aged professionals seeking to improve their English skills in order to improve their career prospects while competing with a young breed of English-proficient colleagues most of whom were products of the Cambridge system.

The British may have introduced the English language for administrative purposes, and the more nefarious intent of establishing cultural hegemony, but post-partition English remains de rigueur because of poor governmental policies, a ramshackle public education system and the hegemony of the English language across the world – it is the predominant language of the Internet and scientific research. Today, being adept in English is highly advantageous, and as a postcolonial nation we have an edge over others who were not brought up in an English-speaking environment. So instead of distancing ourselves from it to hide from our inescapable colonial past, we must take advantage of this circumstance. Let us not forget that the very founding fathers we revere - from Sir Syed Ahmed Khan to Sir Allama Muhammad Iqbal (both of whom accepted the knighthood from British overlords) to Muhammad Ali Jinnah (who, to be fair, rejected the same honorific) - were Anglophiles themselves. In fact, Quaid-e-Azam’s proficiency in English far surpassed his Urdu which was rudimentary at best.

Let's make one thing clear though: English is neither a superior language (far from it), nor is it the language of the superior. But, it is a language that is now a part of our culture, brought to us by conquerors from outside the Indian Subcontinent. We must accept this, for if we deny the language of our past conquerors, we deny Persian, Arabic and Tukish languages whose amalgamation is our most cherished ‘national language’ i.e. Urdu. Without the language of the conquerors, the Subcontinent would still be speaking some variation of Sanskrit or Prakrit (and other local regional languages) that are indigenous to the subcontinent. Interestingly, English and Persian, being Indo European languages, are closer to our native Sanskrit, Prakrit, Punjabi, Sindhi languages than Arabic, which is a Semitic language (like Aramaic and Hebrew) and Turkish which belongs to the Orghuz language family. In fact, Urdu has only 24 genuine Turkish words in its vocabulary.

The fact remains that much like English, the Arabic and Persian languages too were initially alien to native South Asians but eventually made their way into the culture of the Subcontinent. However, the British Raj being a more recent phenomenon, we continue to oppose it even though it has clearly taken root in our culture and our society – and it is here to stay. So, like many postcolonial nations, we too must accept it as one of our local languages as much as the British have to accept that the creolisation of the English language in postcolonial nations is legitimate in its own right. For instance Singaporean English (Singlish), Hindustani English (Hinglish), and Malaysian English (Manglish) are now accepted variations of the English language where the natives have merged their local language with that of the outsiders, which, ironically, is how Urdu was invented as well.

Returning to the conversation between the ladies, their discourse represents the two extremities at the heart of the Urdu – English debate. For us to move forward, it is important to leave this dispute behind by accepting that both these languages - and all the regional languages - are part of our complex and diverse culture, that there is no shame in using either of them, and that effective policies can truly preserve and develop all our languages without having to constantly question each others’ loyalties and degrees of Pakistaniat.