On Empress Nur Jahan’s 375th death anniversary, I present Sahir Ludhianvi’s 'Nur Jahan Ke Mazar Par' which prefigured his yet another celebrated poem, 'Taj Mahal'.

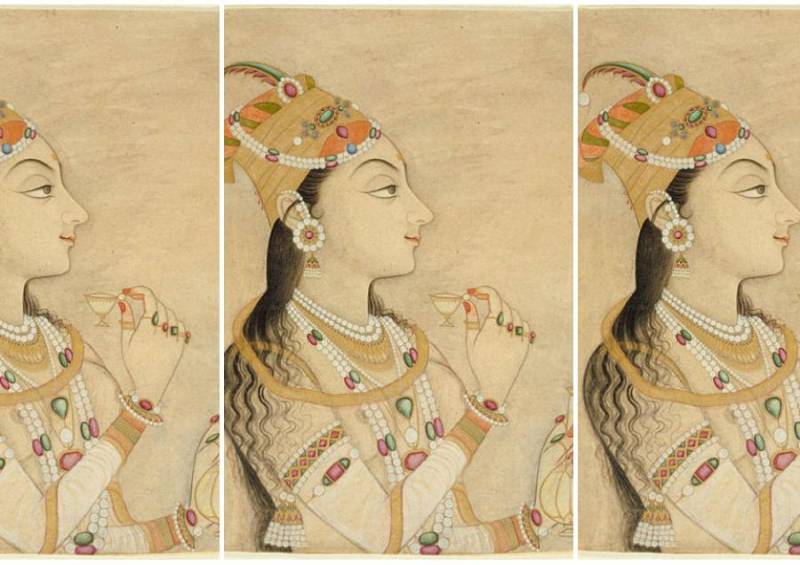

Empress Nur Jahan was the wife of the fourth Mughal Emperor Jahangir. She was born as Mehrunissa in Qandahar on May 31, 1577 and buried in Lahore in a tomb along the river Ravi. She had great love for Lahore, which she expressed in the following (Farsi) couplet:

We have obtained Lahore at the cost of our life

We have bought a new paradise by sacrificing our life '

She was a good poet and had a great taste for literature. Her tomb carries her following verse:

Bar mazar-e-ma ghareeban ne chiraghe ne gule

Ne par-e-parvana yabi ne sarayad bulbule '

(On the grave of this poor stranger, let there be neither lamp nor rose

Let neither butterfly’s wing burn nor nightingale sing)

But in the Indian subcontinent the second verse of this couplet has been made famous as: Ne par-e-parvana sozad ne sada-e-bulbule .

Just as Nur Jahan’s tomb in Lahore served as an inspiration for the more famous Taj Mahal at Agra, interestingly it also served as the inspiration for one of Sahir Ludhianvi’s lesser-known poems as well as one of his best known and most popular ones.

While responding to a query by his friend, the writer and poet Krishan Adeeb, Sahir confessed that he had not visited the Taj Mahal prior to writing his famous poem Taj Mahal; neither had he even been to Agra. Actually he wanted to write a poem on the tomb of empress Nur Jahan but it did not prove a success, therefore he wrote the poem on Taj Mahal. After all, he wondered aloud, what was the need to visit Agra for this purpose? Furthermore, he had studied Karl Marx’s philosophy and also knew something about terrestrial study. He also knew that Shah Jahan had built Taj Mahal along the Jamuna for his wife Mumtaz Mahal.

Sahir’s poem on Nur Jahan’s tomb simply titled 'Nur Jahan Ke Mazar Par' (At the Tomb of Nur Jahan) is part of his best-selling debut poetic collection Talkhiyan (Bitterness), which was published in Lahore even before he turned 25. It also serves to highlight Sahir’s near-forgotten link with Lahore where he spent some of the most memorable years of his life before and after partition, before beating a hasty retreat to Delhi and onto glitzy Bombay.

It begins thus:

Pehlu-e-shah mein yeh dukhtar-e-jamhoor ki qabar

Kitne gum-gashta fasanon ka pata deti hai

Kitne khoon-rez haqaeq se uthati hai naqab

Kitni kuchli hui janon ka pata deti hai '

Like his poem on Taj Mahal, Sahir invokes the tomb of Nur Jahan to rail against patriarchy and royal privilege. But unlike the former poem, our poet is not asking his beloved to meet him elsewhere; rather he is saying to her that unlike Nur Jahan – who was Jahangir’s 20th wife – she is free to reject his advances, since they were equal partners in crime, not bound by royal compulsion.

Toa meri jan! Mujhe hairat-o-hasrat se na dekh

Hum mein koi bhi Jahan Nur-o-Jahangir nahin

Tu mujhe thukra ke bhi ja sakti hai

Tere hathon mein mere hath hen, zanjeer nahin '

This beautiful, little-known poem is now being offered here in my humble English translation, on its subject’s death anniversary, in the hope that it will stimulate renewed interest in Sahir’s memory and legacy, as well his attachment to Lahore, in time for his birth centenary next year in 2021. Here it goes:

This grave of the republic’s daughter, lying at the side of the emperor

Gives trace of so many lost tales of wonder

So many murderous realities were thus unveiled

So many crushed lives were so revealed.

How for the comfort of the arrogant emperors

Bazars of beauties were set up years upon years

How for the pleasure of eyes which strayed

Piles of young bodies in the red palaces were laid.

How from every branch the sealed fragrant blossoms

Were pinched for the decoration of the harems

And even after withering they could not be freed

The reputation of the emperor’s affection so decreed.

How someone’s slight lips’ movement

Could condemn the lamps of generous fidelities to being indifferent

It could loot the caress of the shining hands

It could break the cup full of the wine of love.

In this frightened ambience, this desolate sepulchre

So silent, as if behaving like a pleader

The air in the cold branches is screaming

As if the spirit of purity and fidelity is lamenting.

So my life! Do not look at me with amazement and desire

None of us is Nur Jahan or Jahangir

You can leave me, reject me too with disdain

Your hands hold mine, not a rein.’

Empress Nur Jahan was the wife of the fourth Mughal Emperor Jahangir. She was born as Mehrunissa in Qandahar on May 31, 1577 and buried in Lahore in a tomb along the river Ravi. She had great love for Lahore, which she expressed in the following (Farsi) couplet:

We have obtained Lahore at the cost of our life

We have bought a new paradise by sacrificing our life '

She was a good poet and had a great taste for literature. Her tomb carries her following verse:

Bar mazar-e-ma ghareeban ne chiraghe ne gule

Ne par-e-parvana yabi ne sarayad bulbule '

(On the grave of this poor stranger, let there be neither lamp nor rose

Let neither butterfly’s wing burn nor nightingale sing)

But in the Indian subcontinent the second verse of this couplet has been made famous as: Ne par-e-parvana sozad ne sada-e-bulbule .

Just as Nur Jahan’s tomb in Lahore served as an inspiration for the more famous Taj Mahal at Agra, interestingly it also served as the inspiration for one of Sahir Ludhianvi’s lesser-known poems as well as one of his best known and most popular ones.

While responding to a query by his friend, the writer and poet Krishan Adeeb, Sahir confessed that he had not visited the Taj Mahal prior to writing his famous poem Taj Mahal; neither had he even been to Agra. Actually he wanted to write a poem on the tomb of empress Nur Jahan but it did not prove a success, therefore he wrote the poem on Taj Mahal. After all, he wondered aloud, what was the need to visit Agra for this purpose? Furthermore, he had studied Karl Marx’s philosophy and also knew something about terrestrial study. He also knew that Shah Jahan had built Taj Mahal along the Jamuna for his wife Mumtaz Mahal.

Sahir’s poem on Nur Jahan’s tomb simply titled 'Nur Jahan Ke Mazar Par' (At the Tomb of Nur Jahan) is part of his best-selling debut poetic collection Talkhiyan (Bitterness), which was published in Lahore even before he turned 25. It also serves to highlight Sahir’s near-forgotten link with Lahore where he spent some of the most memorable years of his life before and after partition, before beating a hasty retreat to Delhi and onto glitzy Bombay.

It begins thus:

Pehlu-e-shah mein yeh dukhtar-e-jamhoor ki qabar

Kitne gum-gashta fasanon ka pata deti hai

Kitne khoon-rez haqaeq se uthati hai naqab

Kitni kuchli hui janon ka pata deti hai '

Like his poem on Taj Mahal, Sahir invokes the tomb of Nur Jahan to rail against patriarchy and royal privilege. But unlike the former poem, our poet is not asking his beloved to meet him elsewhere; rather he is saying to her that unlike Nur Jahan – who was Jahangir’s 20th wife – she is free to reject his advances, since they were equal partners in crime, not bound by royal compulsion.

Toa meri jan! Mujhe hairat-o-hasrat se na dekh

Hum mein koi bhi Jahan Nur-o-Jahangir nahin

Tu mujhe thukra ke bhi ja sakti hai

Tere hathon mein mere hath hen, zanjeer nahin '

This beautiful, little-known poem is now being offered here in my humble English translation, on its subject’s death anniversary, in the hope that it will stimulate renewed interest in Sahir’s memory and legacy, as well his attachment to Lahore, in time for his birth centenary next year in 2021. Here it goes:

This grave of the republic’s daughter, lying at the side of the emperor

Gives trace of so many lost tales of wonder

So many murderous realities were thus unveiled

So many crushed lives were so revealed.

How for the comfort of the arrogant emperors

Bazars of beauties were set up years upon years

How for the pleasure of eyes which strayed

Piles of young bodies in the red palaces were laid.

How from every branch the sealed fragrant blossoms

Were pinched for the decoration of the harems

And even after withering they could not be freed

The reputation of the emperor’s affection so decreed.

How someone’s slight lips’ movement

Could condemn the lamps of generous fidelities to being indifferent

It could loot the caress of the shining hands

It could break the cup full of the wine of love.

In this frightened ambience, this desolate sepulchre

So silent, as if behaving like a pleader

The air in the cold branches is screaming

As if the spirit of purity and fidelity is lamenting.

So my life! Do not look at me with amazement and desire

None of us is Nur Jahan or Jahangir

You can leave me, reject me too with disdain

Your hands hold mine, not a rein.’