A report published in the Washington Post (November 21, 2017) declared that nearly all the major cities of the world were facing a serious ‘garbage crises.’ The report quotes a World Bank study that predicts that by 2025 the crisis will worsen as more and more people will move to the already congested urban areas.

According to a study published in Global Citizen (October, 2016) New York City in the United States generates the most garbage. Though much has been done to address this issue with an effective garbage-collecting and recycling mechanism, it is still considered to be a city with a massive trash problem.

The study informs that after New York City, Mexico City ranks as the second highest ‘urban waster.’ Other cities mentioned in the study are Tokyo (Japan), Los Angeles (US), Mumbai (India), Istanbul (Turkey), Jakarta (Indonesia) and Cairo (Egypt).

Most major cities in Africa, especially Laos in Nigeria, have serious trash problems. But unlike in the developed countries, cities in Africa and South Asia have yet to tackle the issue with any effective garbage disposal and recycling mechanisms.

New York City is considered to have had one of the biggest garbage problems in the world.

Garbage often spills over onto the streets in Cairo.

Karachi’s garbage outbreaks

In South Asia, along with Mumbai, Pakistan’s largest metropolis, Karachi, has the worst garbage problem. But interestingly, ever since Karachi evolved into becoming a major urban centre in the late 19th century, it has bounced to and fro from suffering major garbage outbreaks to becoming one of the cleanest cities in the region.

The city has faced at least three major garbage outbreaks which have often emerged in between periods of relative cleanliness. Karachi faced its first outbreak in the late 19th century.

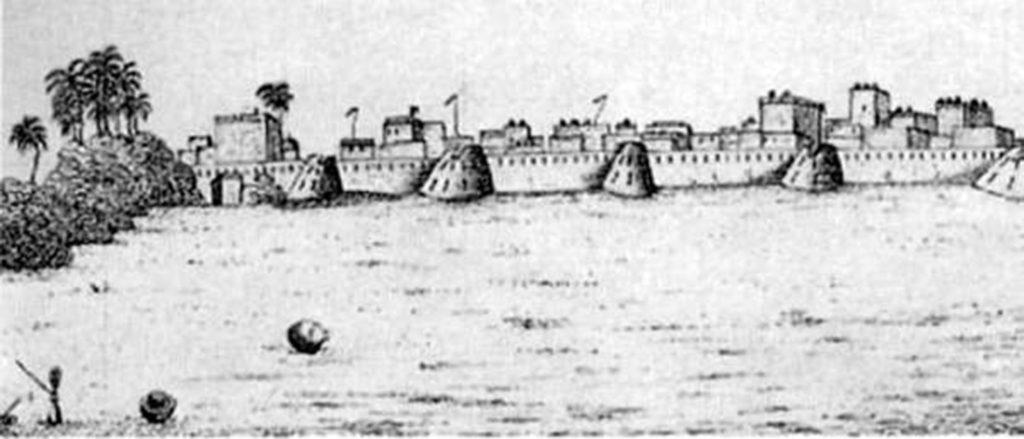

The city was annexed by the British in 1843 and it thus became part of British India. At the time of the annexation, Karachi was a small trading post with a natural harbor.

According to the 1919 Sindh Gazetteer, the city’s population in the 1843 was no more than 20,000. The population was a mix of Hindus and Muslims, largely living in mud huts in the city’s Lyari and Manora areas.

The Gazetteer adds that outside these two areas, the city was barren. It was largely covered by mangrove forests, sand dunes and wild shrubs. It had a variety of birds (mainly kites, sparrows, parrots and crows); and animals such as dogs, cats, wolves, foxes, snakes and even a few panthers. A deep pond near a shrine in Manghopir was full of crocodiles (it still is).

A sketch of Karachi drawn by a British sailor in 1843. At the time the city’s population was just 20,000.

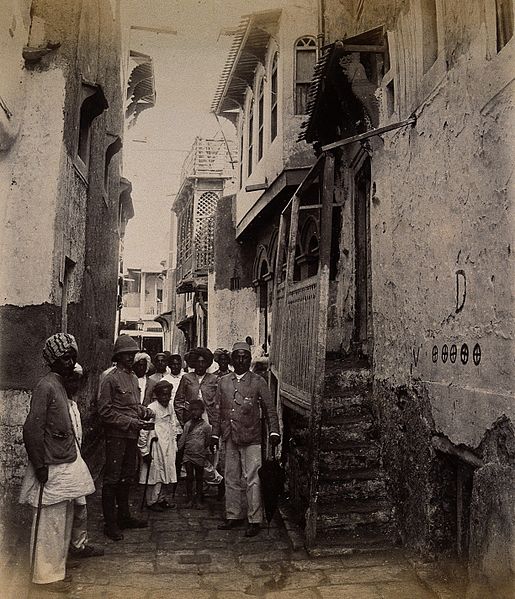

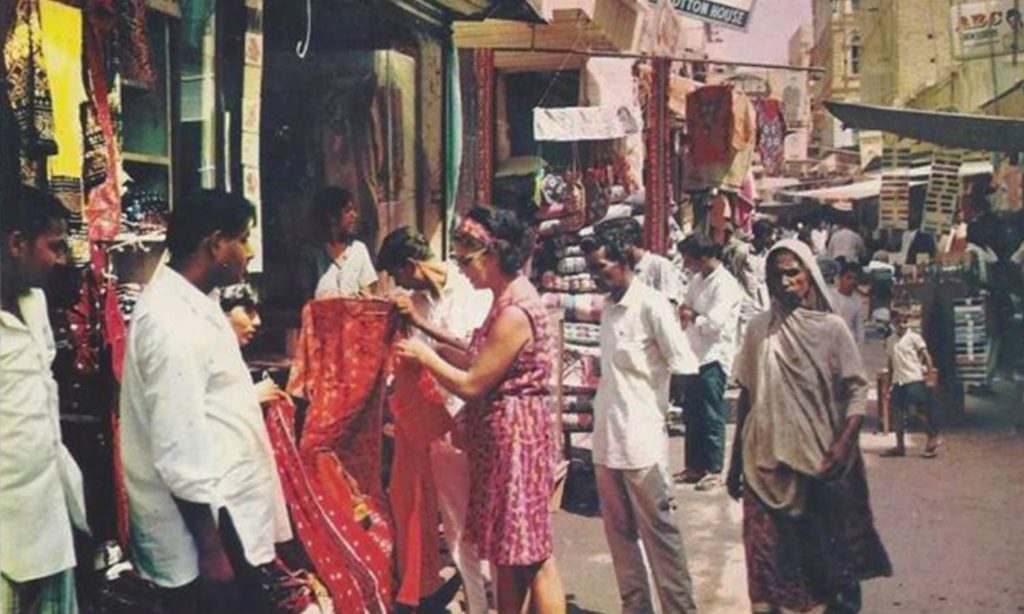

British traveler, geographer and officer, Sir Richard F. Burton, who travelled and stayed in Karachi in the mid and late 19th century wrote that there was a sprinkling of mosques, Sufi shrines and Hindu temples. He also wrote that there were ‘no less than three brothels’ and appalling sanitation conditions.

He described the men of Karachi as hard working but brutish and that the women loved to wear colourful clothes but were ‘very loud.’ The murder rate was high and alcoholism was rampant.

The British began to develop Karachi’s natural harbor and this drew more people to the city. The British developed cleaner ‘cantonment areas’ away from the more populated areas of the city. Karachi’s population grew from 20,000 in the 1840s to almost 100,000 in the early 1890s! The garbage and filth continued to mount, though.

By the 1890s, Karachi’s population had grown to 100,000. This is when the city faced its first major garbage outbreak.

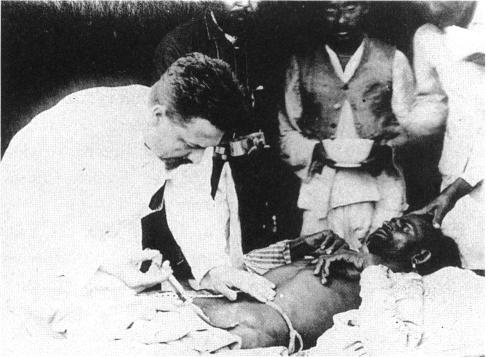

In 1896 rats with fleas carrying the deadly bubonic plague escaped from a ship arriving from Calcutta. Calcutta was already facing a plague epidemic. The rats found ample food in Karachi’s growing garbage dumps and then entered people’s homes. By 1897 the plague had spread across the city’s congested areas, killing hundreds of people.

Thousands of Karachiites were quarantined as British doctors and traditional Muslim and Hindu medicine men tried to contain the outbreak. The plague was finally contained by 1900.

A British doctor treating a victim of the bubonic plague which swept Karachi between 1896 and 1900.

In the early 1900s, the British saw the construction of a complex sewerage system; and garbage disposal and collection mechanism. The administration also undertook regular cleaning of roads and streets (sometimes with water).

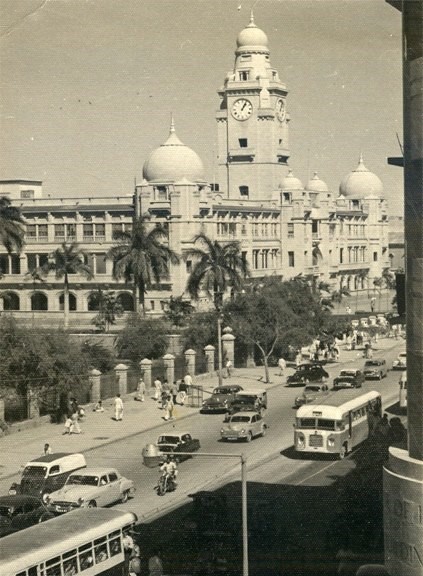

Even though, according to published statistics of the period, the city’s population had grown to over 300,000 by the 1930s, Karachi had risen from filth to become a bustling and lucrative trading and business hub and a preferred place of leisure. It also became one of the cleanest cities in India. It began being dubbed as the 'Paris of Asia'.

By the 1930s, the city had largely resolved its sanitation problems and grew to become an important economic hub and one of the cleanest cities in British India.

A freshly-washed street in Karachi’s Saddar area in 1940s.

A British soldier at a bar in the newly-build Karachi Airport in the 1940s.

In 1947 when Karachi became part of Pakistan, it received a huge influx of millions Its population was 435,887 in 1941 but drastically rose to 1,137, 667 in 1951 (a growth of 161%).

With the city’s resources coming under tremendous stress, the government struggled to accommodate the influx. But a boom in exports of Pakistani agricultural products in 1950-51 somewhat stabilized the situation, especially since Karachi was the country’s only port city and economic hub.

Remarkably, the sanitation mechanism put in place by the British did well to cope with the drastic growth in population. It was further modernized, mostly during the hectic industrialization period initiated by the Ayub Khan regime (1958-69).

Even till the early 1960s, many roads and streets were still being washed with water.

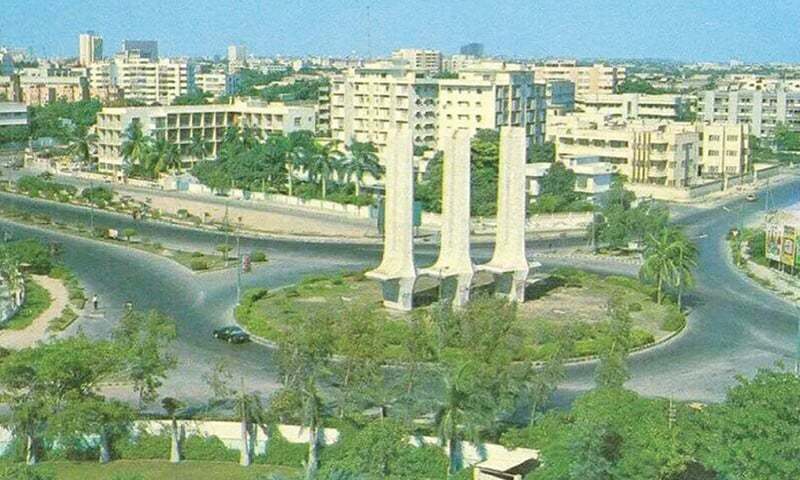

Still clean: Karachi, 1952.

Karachi, 1960.

In the 1960s, the government built housing in the large Korangi area to shift thousands of families squatting in the city’s central areas.

Karachi’s Frere Hall & Garden in the 1960s. Fines were imposed in some areas for littering.

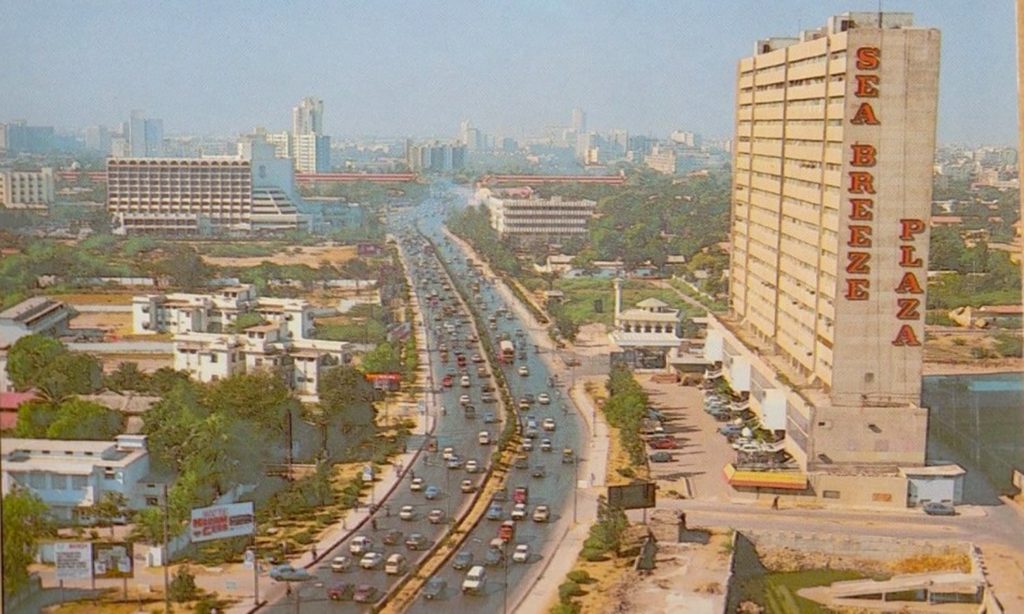

Karachi, 1960s.

The streets and roads of the city were submerged under water after a cyclone hit Karachi in 1965.

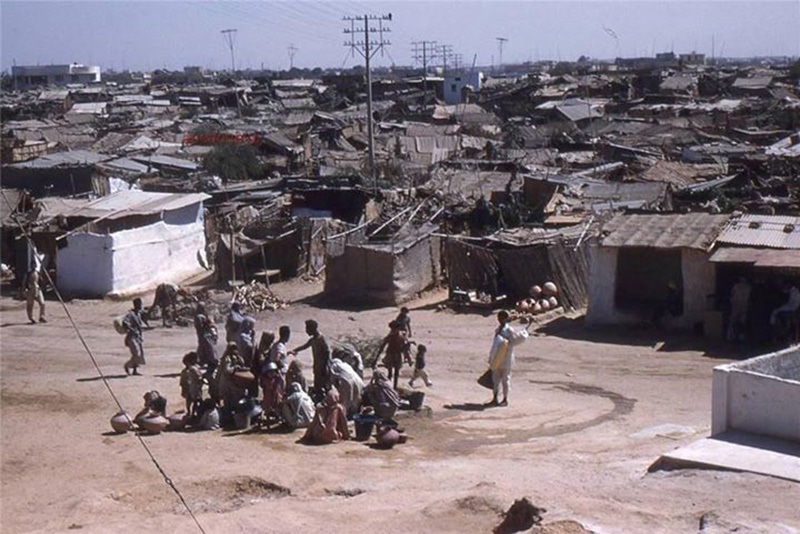

A slum in 1966. Karachi was at the centre of industrialization of the 1960s. As rapid industrialization attracted thousands of white and blue collar labour from other areas of the country, slums in the city began to grow.

Karachi’s population increased from 2,044,044 in 1961 to 3,606,744 in 1972. The government of ZA Bhutto (1971-77) launched a beautification project in 1973. But these struggled to arrest the sanitation and garbage disposal problems the city had begun to face from 1969 onwards.

Karachi’s Teen Talwar area in 1975. The government launched a ‘beautification drive’ in 1973 to arrest the sanitation problem that the city began to face from 1969 onwards.

Karachi, 1972: Many areas of Karachi became extremely congested.

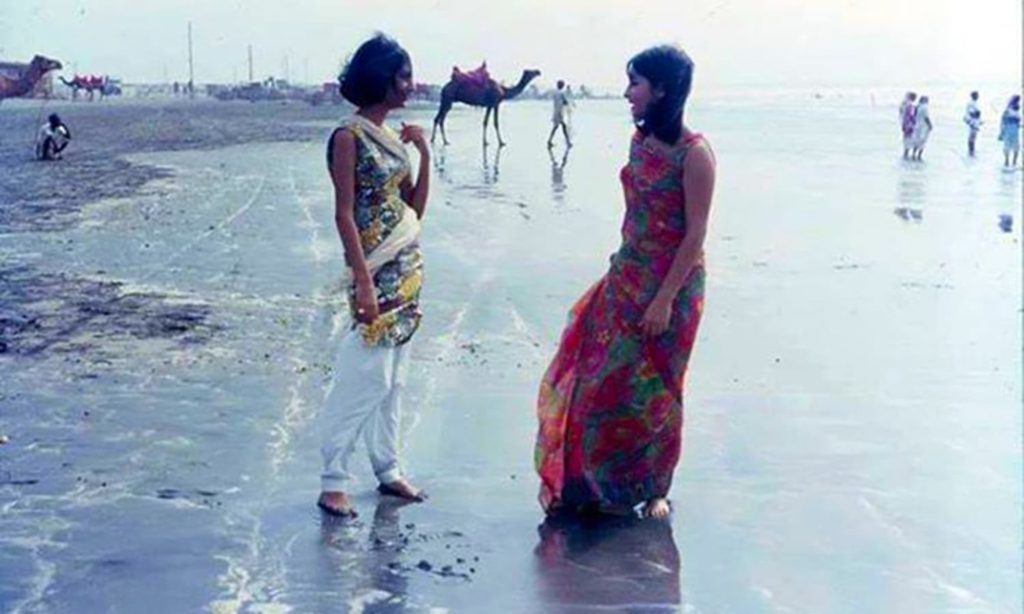

Karachi’s Clifton Beach in 1973. In the years to come it will become one of the most polluted.

The grand casino in Karachi. It was part of the government’s beautification project. It was to be the largest casino in the region with a sprawling gambling area, bars and a 5-star hotel. The government planned to draw rich Arab, American and European tourists to Karachi after the casinos in Beirut closed down due to a civil war there. The Casino was completed in March 1977. But it never opened because alcohol was banned in Pakistan in April 1977 and in July 1977 a reactionary dictatorship took over power.

Karachi witnessed its second major garbage outbreak in the mid-1980s. In the 1980s, the city received its second wave of refugees, this time in the shape of Afghans displaced by the Afghan Civil War. Tensions between Karachi’s Mohajir and Pashtun ethic groups were already mounting. The crime rate in the city had risen sharply and so had drug addiction.

As the city’s resources came under duress, serious ethnic riots erupted in 1986. By the late 1980s, the country’s sanitation mechanism had completely broken down. Things got even worse in the 1990s when ethnic riots left the city paralyzed. By the end of the 1990s, the city cut a sorry sight. Karachi it seemed was a city buried underneath a million tons of filth.

Karachi, 1980: Awaiting another trash catastrophe.

Karachi, 1986: The city’s second major garbage outbreak begins to unfold.

Karachi, late 1990s.

When General Pervez Musharraf came to power (through a military coup) in 1999, he injected millions of rupees to revive Karachi’s economy that had been falling apart.

A lot of this money was also used to kick-start another beautification and cleaning project. An improvement in the overall economy of the country helped the project to become a success and the gloom and the filth that had had been haunting Karachi for so many years was lifted.

Karachi got a facelift in the early 2000s.

The Teen Talwar area in 2007.

Karachi experienced its third major garbage outbreak from 2011 onwards. The problem was largely ignored by the authorities until in 2017 when a report in Dawn warned that ‘the city’s solid waste problem is assuming crisis proportions.’ The report added that ‘in neighborhoods across the city — from the enclaves of the elite to the sprawling urban slums — there are mounds of garbage piling up everywhere, with the provincial government and municipal authorities all at sea about how to solve the problem.’

Debates over the mounting issue between the city’s two largest political parties — the populist left-liberal Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) which presides over the current provincial government in Sindh, and the Mohajir ethnic Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) — often degenerated into becoming animated vocal brawls.

The populist centre-right party, Pakistan Thereek-i-Insaf (PTI), which managed to bag the second largest tally of votes in the city in the 2013 election, seems to have no clue about the rather complex social and political dynamics of the city.

In 2017, real estate tycoon, Malik Riaz, decided to donate millions of rupees, machinery and manpower to lift the ever-rising mounts of garbage in the city.

The PPP government in Sindh responded by importing powerful garbage collecting machines from China and signing a Rs2 billion contract with a Chinese company to process waste in the city. The MQM (now splintered) has attempted to initiate various clean-up campaigns, but the garbage has continued to mount.

Another issue in this regard has been the defacing of walls and monuments with ugly graffiti, posters and paan stains. Graffiti and posters are aimlessly sprayed and pasted by a host of culprits ranging from political party activists, to religious groups, to quacks and small entrepreneurs.

Party flags are hoisted on electricity poles but then forgotten about till they rot and become muddy rags dangling from the poles.

Recently, however, the Sindh government initiated a campaign to wipe clean the graffiti, but much still needs to be done to get rid of the decomposing party flags, posters, paan stains and even a plethora of cable TV wires which can be seen dangling from electricity poles that create a problem for the city’s electric supply company, the K-Electric.

Unfortunately, the people of this city have only added to the problem. Shopkeepers do not hesitate to throw their litter even in front of their own shops. But many Karachiites say one can hardly find a garbage bin anywhere in the city. Therefore, the Sindh government has now placed large and small trash bins and cans in all areas of the city.

The Teen Talwar area in 2007.

The mayor of Karachi, Wasim Akhtar during a ‘Clean Karachi’ campaign.

Citizens take the initiative to clean up the Clifton Beach.

Trash cans ready to be placed all over the city.