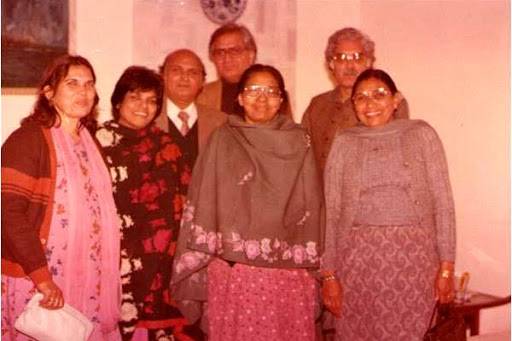

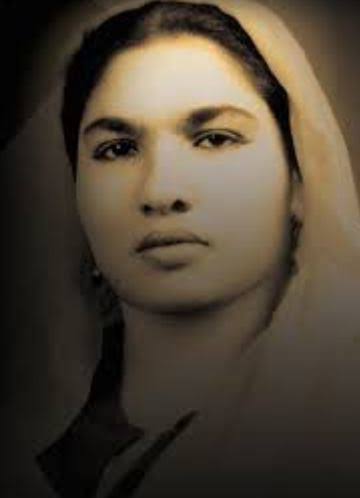

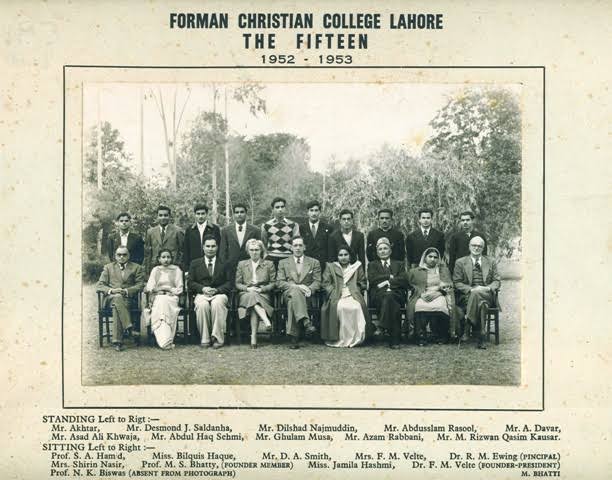

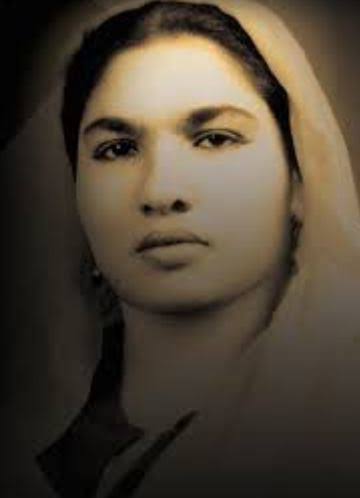

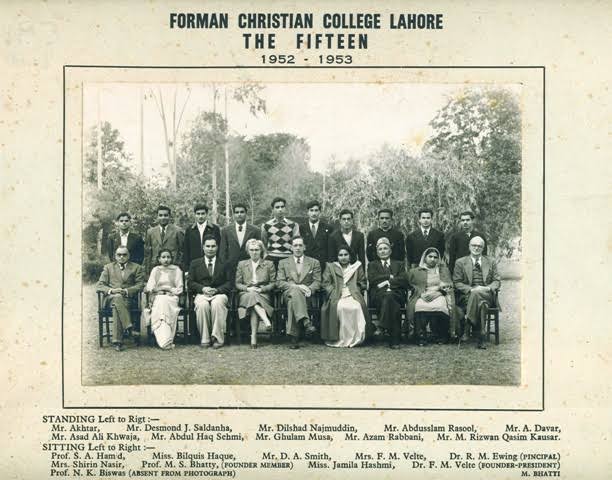

Jamila Hashmi, who celebrates her 92nd birthday today, occupies a distinct place in the evolution of the Urdu novel in Pakistan in the 20th century. Her prestige cannot be measured from the awards of the government or certificates of literary critics, but through the strength of her own labour and craft. In her own time, Hashmi was widely recognized and reviewed as a celebrated writer, yet some 30 odd years after her relatively young death, she has disappeared from literary debates. On the contrary, her contemporaries continue to be celebrated, written about and recognized both at the state and popular levels. Is this literary amnesia due to the fact that she is hard to categorize as a writer; or that perhaps she never looked upon herself as an exclusively ‘female’ writer; or indeed because like many other fortunate writers, she was not part of a dominant literary camp during her lifetime and now does not happen to have a lobby to promote her?

Hashmi’s 90th birthday a couple of years ago went unnoticed. Yet she was recently in the news; Rauf Parekh revisited her notable works in his column last week and the latest issue (Jan-Dec 2020) of Lauh, an Urdu literary magazine published from Rawalpindi, has included Hashmi’s probably most celebrated novel Dasht-i-Soos in its list of the best and/or important Urdu novels written during the last one-and-a-half century. Perhaps, with the absence of anything else, that could be regarded as something of an achievement, if at all! (Never mind that this list omits the works of the late Hijab Imtiaz Ali and Fahmida Riaz and senior and important contemporary female writers Jilani Bano, Zaheda Hina, Neelum Ahmad Bashir and Tahira Iqbal as well as the promising younger writer Amna Mufti).

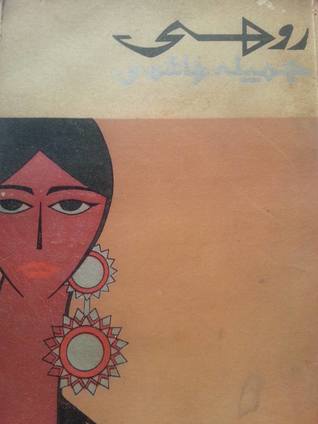

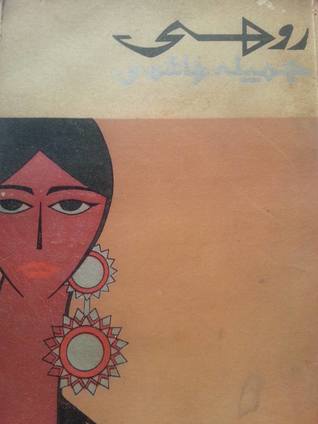

However, it is not Hashmi’s aforementioned novel that concerns me here, but an earlier work Rohi which was published in August 1970, therefore marking its 50th year of publication. It is dedicated to her daughter ‘Ashi’, better known to us today as the distinguished scholar Dr Ayesha Siddiqa. Rohi is the story of that desert of Rohi spread over an area of thousands of miles where even the basic requirements of life are not easily available. Water is scarce, in fact rare, and that is why the life of the dwellers of Rohi is a continuous journey. They wander from one place to another with their animals in search of water while bearing the hardships of seasons along. In the summer when even the cities heat up to become hell, one cannot even imagine the weather of a desert. Storms which pick the mountains of sand to take them elsewhere; sand upon which neither there are the traces of any pathways and nor can a way be made therein. People travel under the shade of stars and find the way with the help of stars. Surrounded by mirages, they continue the search for water.

But this Rohi has another shape too. When the rainy season arrives then Rohi becomes populated, its solitude and desolation turns into happiness. The slender cucumber-like clouds, the showers of rain, drip-drop, multi-coloured lightnings glow. Rain falls with a patter. The weather is lively. In such weather, the women put on edges of rouge and kajal, bangles and make-up, anklets and kurtas embellished with mirrors. They wear dupattas of embroidered stars and make their hair glow by applying wax. Then a storm of colour erupts in the population of Rohi. Fairs are held with dances all night.

Khawaja Ghulam Farid was so enchanted by this beauty of Rohi that he led the life of a hermit there for 18 years continuously. His poetry is the poetry of the beauty and youth of Rohi; a continuous tale of its loveliness and allure; the story of the youth of the virgins of Maar and the condition of the emotions arising within the heart at that time. The story of Rohi is very much the same. The hardships and adversities of this life, its beauty and bloom, has been sewn into the warp and woof of this section. The quaint customs and music of the songs with lengthy tunes found here together with the intervention of strangers in this life which can never be complete, since they forever remain strangers. The soldiers and the son of the Nawab of Ranhal post are all strangers; they eventually have to return, defeated. Maryam who has the courage to look both life and death boldly in the face, is clever despite her simplicity. Her brother and father, Gari Khan and Buland Khan are all shadows. Only she is the actual reality. She is informed of herself everywhere while grazing the sheep, milking them, during the rain. There is a ridicule in her eyes which is a challenge for the son of the Nawab and she herself is his competition. In the end, we think that it all ended well.

Rohi was incidentally published as a long short-story in the journal Naya Daur. Most people did not notice it then because in this country nobody read literary journals in those days.

Then Rohi was published later by Maktaba-e-Jadid in book form with an eye-catching cover design by Aslam Kamal. One can deem it a long short-story and a ‘novella’ too. The writer as we know is an experienced story-teller and weaves the warp and woof of her stories with great skill and dexterity. How many of us even first-time readers have been able to forget the magic of her stories Aatish-e-Rafta (Deceased Passion) and Laal Aandhi (Red Tempest) after the passage of so many years? Rohi definitely does not awaken a magic like Aatish-e-Rafta, though the writer has kept the flow of narrative and prepared her plot with hard work and expertise. I think while writing Rohi, that thing which Hemingway used to call ‘writer’s luck’ was not with the writer. The plot, characters, topography are all correct but that nameless artistic fire which creates intensity within prose and takes the reader flying away on a wild horse so to speak somehow could not be created. While reading Aatish-e-Rafta one feels that the story is writing itself, both the writer and reader are lost in its shining golden milieu. On the other hand, Rohi seems like a story thought and created upon a rule and arrangement; it is definitely interesting to read but with a mixture of stage. Perhaps it is pointless and unproductive to compare Rohi with Aatosh-e-Rafta. The first burst like a forest spring with deep subconscious, the second was prepared as a jigsaw puzzle at the conscious level with intervals.

Regardless, the writer has very much been successful at conquering the romance of Rohi with all her ability and experience. The Rohi of bare plains and sandy tibbas, where the wind blows strong, swift and clean everywhere; where flocks of deer take flight and the houbara bustards arriving from snowy Siberia descend to rest and feed in the desert bushes; where the Rohillas with their rakish, sharp features and tidy bodies journey upon camels from their far away settlements containing stores of water, while their wives and the beloved keep waiting for them in thickets. There is the solitude and severity of the desert in Rohi but the sights of Rohi – its flocks clotted with their mat seats, its brown sandy mounds, its one or two thickets and oleander trees – are extremely beautiful. And Rohi is more beautiful and dignified than the sea because the colours of Rohi keep changing with the various seasons and times. And the women of Rohi, dashing, with powdered lips, decorated with silver jewelry, are much more charming to the heart than mermaids. It was a woman of Rohi who made a poet mad in her love and in whose separation he wrote a few of the immortal burning poems of the world in Seraiki.

Despite a contrived plot, Rohi is present in this novella because the writer was married into the land of the Rohis and lived there. Now if the writer’s luck was not with her, we cannot blame her. This circumstance or misfortune often takes hold of us all.

But the novella is riveting and even after 50 years of its publication is worth re-reading. For the lovers of Rohi, it is an essential reference.

Note: All translations are by the writer.

Hashmi’s 90th birthday a couple of years ago went unnoticed. Yet she was recently in the news; Rauf Parekh revisited her notable works in his column last week and the latest issue (Jan-Dec 2020) of Lauh, an Urdu literary magazine published from Rawalpindi, has included Hashmi’s probably most celebrated novel Dasht-i-Soos in its list of the best and/or important Urdu novels written during the last one-and-a-half century. Perhaps, with the absence of anything else, that could be regarded as something of an achievement, if at all! (Never mind that this list omits the works of the late Hijab Imtiaz Ali and Fahmida Riaz and senior and important contemporary female writers Jilani Bano, Zaheda Hina, Neelum Ahmad Bashir and Tahira Iqbal as well as the promising younger writer Amna Mufti).

However, it is not Hashmi’s aforementioned novel that concerns me here, but an earlier work Rohi which was published in August 1970, therefore marking its 50th year of publication. It is dedicated to her daughter ‘Ashi’, better known to us today as the distinguished scholar Dr Ayesha Siddiqa. Rohi is the story of that desert of Rohi spread over an area of thousands of miles where even the basic requirements of life are not easily available. Water is scarce, in fact rare, and that is why the life of the dwellers of Rohi is a continuous journey. They wander from one place to another with their animals in search of water while bearing the hardships of seasons along. In the summer when even the cities heat up to become hell, one cannot even imagine the weather of a desert. Storms which pick the mountains of sand to take them elsewhere; sand upon which neither there are the traces of any pathways and nor can a way be made therein. People travel under the shade of stars and find the way with the help of stars. Surrounded by mirages, they continue the search for water.

But this Rohi has another shape too. When the rainy season arrives then Rohi becomes populated, its solitude and desolation turns into happiness. The slender cucumber-like clouds, the showers of rain, drip-drop, multi-coloured lightnings glow. Rain falls with a patter. The weather is lively. In such weather, the women put on edges of rouge and kajal, bangles and make-up, anklets and kurtas embellished with mirrors. They wear dupattas of embroidered stars and make their hair glow by applying wax. Then a storm of colour erupts in the population of Rohi. Fairs are held with dances all night.

Khawaja Ghulam Farid was so enchanted by this beauty of Rohi that he led the life of a hermit there for 18 years continuously. His poetry is the poetry of the beauty and youth of Rohi; a continuous tale of its loveliness and allure; the story of the youth of the virgins of Maar and the condition of the emotions arising within the heart at that time. The story of Rohi is very much the same. The hardships and adversities of this life, its beauty and bloom, has been sewn into the warp and woof of this section. The quaint customs and music of the songs with lengthy tunes found here together with the intervention of strangers in this life which can never be complete, since they forever remain strangers. The soldiers and the son of the Nawab of Ranhal post are all strangers; they eventually have to return, defeated. Maryam who has the courage to look both life and death boldly in the face, is clever despite her simplicity. Her brother and father, Gari Khan and Buland Khan are all shadows. Only she is the actual reality. She is informed of herself everywhere while grazing the sheep, milking them, during the rain. There is a ridicule in her eyes which is a challenge for the son of the Nawab and she herself is his competition. In the end, we think that it all ended well.

Rohi was incidentally published as a long short-story in the journal Naya Daur. Most people did not notice it then because in this country nobody read literary journals in those days.

Then Rohi was published later by Maktaba-e-Jadid in book form with an eye-catching cover design by Aslam Kamal. One can deem it a long short-story and a ‘novella’ too. The writer as we know is an experienced story-teller and weaves the warp and woof of her stories with great skill and dexterity. How many of us even first-time readers have been able to forget the magic of her stories Aatish-e-Rafta (Deceased Passion) and Laal Aandhi (Red Tempest) after the passage of so many years? Rohi definitely does not awaken a magic like Aatish-e-Rafta, though the writer has kept the flow of narrative and prepared her plot with hard work and expertise. I think while writing Rohi, that thing which Hemingway used to call ‘writer’s luck’ was not with the writer. The plot, characters, topography are all correct but that nameless artistic fire which creates intensity within prose and takes the reader flying away on a wild horse so to speak somehow could not be created. While reading Aatish-e-Rafta one feels that the story is writing itself, both the writer and reader are lost in its shining golden milieu. On the other hand, Rohi seems like a story thought and created upon a rule and arrangement; it is definitely interesting to read but with a mixture of stage. Perhaps it is pointless and unproductive to compare Rohi with Aatosh-e-Rafta. The first burst like a forest spring with deep subconscious, the second was prepared as a jigsaw puzzle at the conscious level with intervals.

Regardless, the writer has very much been successful at conquering the romance of Rohi with all her ability and experience. The Rohi of bare plains and sandy tibbas, where the wind blows strong, swift and clean everywhere; where flocks of deer take flight and the houbara bustards arriving from snowy Siberia descend to rest and feed in the desert bushes; where the Rohillas with their rakish, sharp features and tidy bodies journey upon camels from their far away settlements containing stores of water, while their wives and the beloved keep waiting for them in thickets. There is the solitude and severity of the desert in Rohi but the sights of Rohi – its flocks clotted with their mat seats, its brown sandy mounds, its one or two thickets and oleander trees – are extremely beautiful. And Rohi is more beautiful and dignified than the sea because the colours of Rohi keep changing with the various seasons and times. And the women of Rohi, dashing, with powdered lips, decorated with silver jewelry, are much more charming to the heart than mermaids. It was a woman of Rohi who made a poet mad in her love and in whose separation he wrote a few of the immortal burning poems of the world in Seraiki.

Despite a contrived plot, Rohi is present in this novella because the writer was married into the land of the Rohis and lived there. Now if the writer’s luck was not with her, we cannot blame her. This circumstance or misfortune often takes hold of us all.

But the novella is riveting and even after 50 years of its publication is worth re-reading. For the lovers of Rohi, it is an essential reference.

Note: All translations are by the writer.