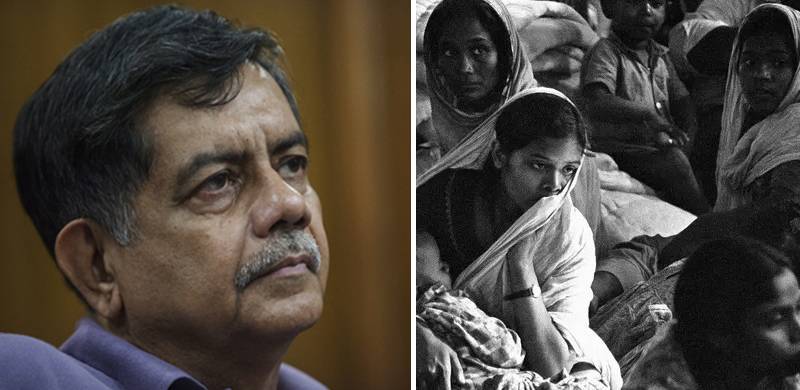

Professor Dr Chowdhury Rafiqul Abrar is teaching international relations at University of Dhaka. He is also coordinator of a resource center called Refugee and Migratory Movements Research Unit.

He was educated at the University of Dhaka and University of Sussex before doing his PhD from Lisbon. He has been in the past engaged in democratic movements and human rights activism. He still maintains some contacts with various organizations working in these fields.

Dr Abrar has written a book along with former Bangladesh foreign minister Professor Shamsul Haq on Aid, Development and Diplomacy. Then he changed his field of study and started concentrating on migration issues, like refugee rights and labour migrants rights.

Recently he was in Lahore to work as a resource person at a seminar and I had the pleasure to have a conversation with him.

What is the condition of 'Biharis' or 'stranded Pakistanis' in Bangladesh?

I call them a forsaken minority. It's a shame that these people have been forgotten. It is a statement on the total and abject failure of political leadership in this region. They have failed to address this problem. These are poor people who migrated at one time. They supported the state of Pakistan leaving their homes in India.

In very difficult circumstances they picked up their lives again in then Pakistan. But they basically became pawns of the political developments in East Pakistan. Rather they have been used by Pakistani civil-military bureaucracy. In 1971, they happened to be on the wrong side of the fence and were branded collaborators immediately after the war.

But I must say that the whole community did not collaborate.

The second issue pertains to Pakistan. Successive rulers in Pakistan have promised these people that they will be taken back, at least a section of them. Except for Benazir Bhutto, everyone is on record saying that they are going to be taken back. The position some of them have taken is that although we don't have any legal obligation but due to Islamic considerations we are going to take them back.

But this process has not taken place because of internal political trouble in Pakistan, particularly in Sindh. This is a humanitarian issue that needs to be addressed by the political leadership. Leadership of stranded Pakistani community is archaic, backward looking. It has failed to provide effective leadership to the community. As a result a group has emerged in the community, with vested interest in maintaining the status quo. This group takes away a big chunk of whatever Bangladesh government provides to the community. This has kept the issue of repatriation going.

I believe ground realities have changed. Most of the people want to stay back and would like to take up Bangladeshi citizenship. In fact, Bangladeshi government did offer citizenship to them soon after 1971. Those who left the camp were absorbed automatically. But there were many who stayed in the camp with the hope that the war will be over and they would end up on the winning side. There should be some survey of their numbers and good sense should prevail between these two countries whereby some amicable arrangement may be made for the split families to reunite. Rest of them should be given Bangladeshi nationality. I think they are Bangladeshi nationals and their case should be pursued vigorously. It is a good news that ten people, who were born after Bangladesh came into being, went to the high court and got a decision in their favour. The court told the election commission to enroll them as voters. Interesting case law is emerging where Biharis are being given Bangladeshi citizenship.

On the other hand, we believe that enlightened Pakistanis and Pakistani Intelligentsia should also come forward and take up this humanitarian issue. They should campaign for the repatriation of the families who would still like to come to Pakistan.

Do you believe that some migrations in our part of the world are taking place because of development activities, especially big dams.

Construction of large dams has been subject to a lot of international criticismand over the years, there have been major international movements in order to stop the construction of large dams which disproportionately affect lives of the poor and marginalized indigenous communities.

The benefits of these dams completely elude those affected by them. In many instances, people are forced to evict to make way for water reservoirs. These people, at times, are not provided with adequate compensation. In other cases, it is very difficult for them to restart their lives.

One instance of all this happening has been Chakma problem in Bangladesh. It is one of those problems that ultimately lead to major hardships, affecting national integration. We need not go into its detail. I am glad that those who favour big dams or who oppose them have started discussing the issue, by setting up an independent commission on dams.

If you look at data, between 1975-85 every year World Bank was funding 26 dams but there has been a significant drop in these numbers during the subsequent decade. In those ten years, the banks funded only four projects every year. As protests against dams became fiercer, financing agencies become less interested in providing funds. And also there is an expectation at the World Bank that private sector would pick up where the bank has left. But basically because large amounts of money are involved, private sector has not come up with its investment plans. The other factors hampering private investment have been the time involved and the environmental legislation that is coming about in some countries.

The review of the World Bank policies undertaken by Operational Evolution Department in 1990 found that at least five dams that the bank financed did not meet its standards. Two of these dams are located in South Asia -- Mangla Dam in Pakistan and Kulay Khani Dam in Nepal. The review team wondered what made the bank fund these projects when they did not meet its standards. Over the years, however, these standards have gone further up, which has rendered about 50 dams unacceptable.

How do you categorize people who become displaced within the boundaries of a country?

I call them 'Oustees'. There are some international norms about people who are forced to leave their country and thus become refugees. But those who have been forced to leave their homes but not their country, become nobody's children. The concept of 'oustees' is ideological. It highlights the fact that they were not participants in the decision to evict them.

In a way, they were forced to move. This coercive aspect is reflected in 'oustees'. It is yet to gain acceptance but I believe that many people do not get a fair deal when they are ousted from their property.

He was educated at the University of Dhaka and University of Sussex before doing his PhD from Lisbon. He has been in the past engaged in democratic movements and human rights activism. He still maintains some contacts with various organizations working in these fields.

Dr Abrar has written a book along with former Bangladesh foreign minister Professor Shamsul Haq on Aid, Development and Diplomacy. Then he changed his field of study and started concentrating on migration issues, like refugee rights and labour migrants rights.

Recently he was in Lahore to work as a resource person at a seminar and I had the pleasure to have a conversation with him.

What is the condition of 'Biharis' or 'stranded Pakistanis' in Bangladesh?

I call them a forsaken minority. It's a shame that these people have been forgotten. It is a statement on the total and abject failure of political leadership in this region. They have failed to address this problem. These are poor people who migrated at one time. They supported the state of Pakistan leaving their homes in India.

In very difficult circumstances they picked up their lives again in then Pakistan. But they basically became pawns of the political developments in East Pakistan. Rather they have been used by Pakistani civil-military bureaucracy. In 1971, they happened to be on the wrong side of the fence and were branded collaborators immediately after the war.

But I must say that the whole community did not collaborate.

The second issue pertains to Pakistan. Successive rulers in Pakistan have promised these people that they will be taken back, at least a section of them. Except for Benazir Bhutto, everyone is on record saying that they are going to be taken back. The position some of them have taken is that although we don't have any legal obligation but due to Islamic considerations we are going to take them back.

But this process has not taken place because of internal political trouble in Pakistan, particularly in Sindh. This is a humanitarian issue that needs to be addressed by the political leadership. Leadership of stranded Pakistani community is archaic, backward looking. It has failed to provide effective leadership to the community. As a result a group has emerged in the community, with vested interest in maintaining the status quo. This group takes away a big chunk of whatever Bangladesh government provides to the community. This has kept the issue of repatriation going.

I believe ground realities have changed. Most of the people want to stay back and would like to take up Bangladeshi citizenship. In fact, Bangladeshi government did offer citizenship to them soon after 1971. Those who left the camp were absorbed automatically. But there were many who stayed in the camp with the hope that the war will be over and they would end up on the winning side. There should be some survey of their numbers and good sense should prevail between these two countries whereby some amicable arrangement may be made for the split families to reunite. Rest of them should be given Bangladeshi nationality. I think they are Bangladeshi nationals and their case should be pursued vigorously. It is a good news that ten people, who were born after Bangladesh came into being, went to the high court and got a decision in their favour. The court told the election commission to enroll them as voters. Interesting case law is emerging where Biharis are being given Bangladeshi citizenship.

On the other hand, we believe that enlightened Pakistanis and Pakistani Intelligentsia should also come forward and take up this humanitarian issue. They should campaign for the repatriation of the families who would still like to come to Pakistan.

Do you believe that some migrations in our part of the world are taking place because of development activities, especially big dams.

Construction of large dams has been subject to a lot of international criticismand over the years, there have been major international movements in order to stop the construction of large dams which disproportionately affect lives of the poor and marginalized indigenous communities.

The benefits of these dams completely elude those affected by them. In many instances, people are forced to evict to make way for water reservoirs. These people, at times, are not provided with adequate compensation. In other cases, it is very difficult for them to restart their lives.

One instance of all this happening has been Chakma problem in Bangladesh. It is one of those problems that ultimately lead to major hardships, affecting national integration. We need not go into its detail. I am glad that those who favour big dams or who oppose them have started discussing the issue, by setting up an independent commission on dams.

If you look at data, between 1975-85 every year World Bank was funding 26 dams but there has been a significant drop in these numbers during the subsequent decade. In those ten years, the banks funded only four projects every year. As protests against dams became fiercer, financing agencies become less interested in providing funds. And also there is an expectation at the World Bank that private sector would pick up where the bank has left. But basically because large amounts of money are involved, private sector has not come up with its investment plans. The other factors hampering private investment have been the time involved and the environmental legislation that is coming about in some countries.

The review of the World Bank policies undertaken by Operational Evolution Department in 1990 found that at least five dams that the bank financed did not meet its standards. Two of these dams are located in South Asia -- Mangla Dam in Pakistan and Kulay Khani Dam in Nepal. The review team wondered what made the bank fund these projects when they did not meet its standards. Over the years, however, these standards have gone further up, which has rendered about 50 dams unacceptable.

How do you categorize people who become displaced within the boundaries of a country?

I call them 'Oustees'. There are some international norms about people who are forced to leave their country and thus become refugees. But those who have been forced to leave their homes but not their country, become nobody's children. The concept of 'oustees' is ideological. It highlights the fact that they were not participants in the decision to evict them.

In a way, they were forced to move. This coercive aspect is reflected in 'oustees'. It is yet to gain acceptance but I believe that many people do not get a fair deal when they are ousted from their property.