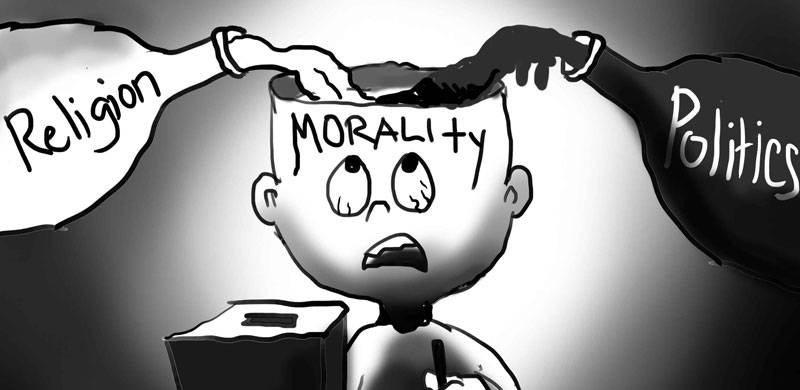

Pakistani morality is like Atif Aslam’s videos. Most recently his naat (devotional hymn for the Prophet), Mustafa Jaane Rehmat, was released. It has elements of nostalgia for those who faithfully observed this naat after Friday prayers in Barelvi mosques. Though, barely three weeks ago, a very seductive and sultry rendition of Chale To Kat Hi Jayega was released. It featured a blonde fair skinned woman gyrating around him in a fantasy bedroom. This too was a throwback to the past when legendary Pakistani singer Mussarat Nazir made the song immortal in the 1980s. In both cases, Atif Aslam’s strategy was to milk the nostalgia industry and his appeal was towards his audience, whose morality holds space for both the sacred and the profane despite their loud protests against the “secular” or the “liberal”.

Indeed, in the age of YouTube, music entrepreneurs like Atif Aslam cater to what brings forth the greatest number of likes and shares. To be fair, the sultry video is relatively tame in a world that is rife with sexualized images. But it does make one question the morality of the whole situation where corporatization allows entrepreneurs to sell spirituality, which confers an emotional high (bereft of any transformative capacity), and as just another product as a sexually charged fantasy. In both cases, the product offers an artificially induced experience, which necessitates the question whether Pakistani morality needs a new script.

However, Pakistani entrepreneurs are not the only ones supplying artificially manufactured emotions and experiences. YouTube is teeming with western vloggers who share their travel videos of Pakistan and other western folks who share their reactions to Pakistani music. In one sense, this phenomenon brings people together globally through such online cultural exchange, and which is much needed for Pakistanis who find the image of Pakistan tarnished by the scourge of terrorism. Yet, something is awry when life experiences are reduced to products for consumption purposes and genuine living is replaced by artificial display for likes, shares and monetary gains. Additionally, for attention starved Pakistanis, it replaces deeper introspection, personal accountability and transformative change with superficial validation or pat on the back from western folks.

No wonder, Pakistanis are able to show great hospitality to western travellers but show utter disregard or indifference towards the plight of fellow Pakistani minorities. Such a dichotomy is possible when life is lived for external validation and not internal reflection. Returning to Atif Aslam’s videos, they masterfully capture this dichotomy in Pakistani morality when in just three weeks’ time, the singer catered to both the sacred and the profane, so that Pakistani men can live out their sexual fantasies and wash it with ritualistic devotion.

Unless the moral script changes to replace artificial display with genuine living, and external validation with personal accountability, Pakistani morality will continue to allow hospitality to foreigners but indifference to their own, and it will continue to allow entrepreneurs to keep milking, monetizing and amassing gains from the shallow lives of the unthinking online masses.

Indeed, in the age of YouTube, music entrepreneurs like Atif Aslam cater to what brings forth the greatest number of likes and shares. To be fair, the sultry video is relatively tame in a world that is rife with sexualized images. But it does make one question the morality of the whole situation where corporatization allows entrepreneurs to sell spirituality, which confers an emotional high (bereft of any transformative capacity), and as just another product as a sexually charged fantasy. In both cases, the product offers an artificially induced experience, which necessitates the question whether Pakistani morality needs a new script.

However, Pakistani entrepreneurs are not the only ones supplying artificially manufactured emotions and experiences. YouTube is teeming with western vloggers who share their travel videos of Pakistan and other western folks who share their reactions to Pakistani music. In one sense, this phenomenon brings people together globally through such online cultural exchange, and which is much needed for Pakistanis who find the image of Pakistan tarnished by the scourge of terrorism. Yet, something is awry when life experiences are reduced to products for consumption purposes and genuine living is replaced by artificial display for likes, shares and monetary gains. Additionally, for attention starved Pakistanis, it replaces deeper introspection, personal accountability and transformative change with superficial validation or pat on the back from western folks.

No wonder, Pakistanis are able to show great hospitality to western travellers but show utter disregard or indifference towards the plight of fellow Pakistani minorities. Such a dichotomy is possible when life is lived for external validation and not internal reflection. Returning to Atif Aslam’s videos, they masterfully capture this dichotomy in Pakistani morality when in just three weeks’ time, the singer catered to both the sacred and the profane, so that Pakistani men can live out their sexual fantasies and wash it with ritualistic devotion.

Unless the moral script changes to replace artificial display with genuine living, and external validation with personal accountability, Pakistani morality will continue to allow hospitality to foreigners but indifference to their own, and it will continue to allow entrepreneurs to keep milking, monetizing and amassing gains from the shallow lives of the unthinking online masses.