Enigmatic is the ways of nature as it conceals the consequences of a human achievements and successful inventions during their emergence in a particular time and space. Working under some inexplicable inexorability, over the long duration, the nature turns the achievements of mankind into failures. It is the case with industrial revolution. It introduced marvelous innovations of science and rationalisation of institutional arrangements.

The world entered into the twentieth century with the belief that science and disenchanted worldview of rationality would usher humanity into a new era of peace, leisure, prosperity and progress. It was hoped that the scientific progress would end the miseries and sufferings that humans faced since the time immemorial in their interaction with nature.

In the historical shift brought about by industrial revolution, the train, telegraph, telephone and electricity were just a prologue of the brave new world. Since then, mankind has been witnessing the ever-increasing miracles of technology and its impact on society and the world.

However, the world started to realise unintended consequences of unbridled passion to turn everything and entity into resource and modern penchant for innovation on the very life support system of our planet.

At the turn of the twentieth century, we rejoiced at the disenchantment of our world by rational élan of modernity. What we do not realise today is that humans are undergoing a process of second disenchantment. However, this time it is disenchantment from the disenchanted world of instrumental rationality. The consequences of instrumentalisation of the natural world and life world appear in the shape of existential threat to the planet by environmental degradation and climate change.

To ward off the threats emanating from warming of our globe, it is indispensable to bring the world together to view global warming as a collective threat for all the living beings on the planet.

To reflect upon issues and challenges pertaining to climate change, the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) arranged the ‘International Forum on the Cryosphere and Society: The Voice of the HKH’ from 28-30 August 2019, in Kathmandu, Nepal.

The main objective of the forum was to bring together regional and international experts and stakeholders to establish a better understanding of the framework of cryosphere and explore the links between the cryosphere and communities inhabiting mountains and downstream regions.

In the forum, key scientists from the region, the international scientific community, social scientists, community representatives, different user groups and decision-makers came together and established a dialogue about the cryosphere, its role and its importance for the society of the Hindu Kush-Himalaya region (HKH). They explored different themes related to the cryosphere and society.

Although the conference provided an excellent opportunity for relevant people to reflect upon the issue of cryosphere and society from multiple angles, the scientific perspective remained dominant. However, an interactive session on ‘Cryosphere contribution to spiritual, symbolic, cultural, and religious perceptions’ provided interesting insights into relationship between crises in the symbolic world and global warming.

To demonstrate the validity of this claim, it is better to provide a case study of a society whose symbolic world, life world, identity, cultural metaphors and material culture are all shaped by cryosphere.

In Pakistan, Gilgit-Baltistan forms a cryosphere that benefit inhabitants of mountainous region and downstream communities. It is near Gilgit town where the mighty massifs of the Karakoram, the Hindu Kush and Himalaya meet. Together with Pamir, Kunlun Shan, Tien Shan mountain ranges, the whole region spanning from the Hindu Kush to Himalaya forms the water tower of Asia.

Given the cryospheric characteristics of local culture, it can be said that through human interaction with cryosphere and geography, the culture and symbolic world of Gilgit-Baltistan has been formed. It is visible in its animistic worldview and indigenous knowledge.

A salient feature of this worldview is that there is no dichotomy between human and nature in its cosmological order; rather it treats human as a part of the bigger whole called nature. This animistic framework of mind infused symbolic meaning and vitality to the things both animate and inanimate.

That is why juniper and willow trees, snow clad mountains, mighty boulders, brooks, meadows, and lakes are suffused with symbolic meaning. It is this symbolic order and its relationship with nature that saved the natural world from blatant human interference.

In the traditional animistic/shamanistic cosmology of Gilgit-Baltistan, human beings stand in the middle between pure beings of fairies and deities above and evil beings below. In traditional cosmology, different deities and fairies inform their mundane and metaphysical affairs. Interestingly, all the deities in local cosmology of Gilgit-Baltistan are women who inform the vision of the shaman who guides people regarding their relationship with nature and their conduct in society.

Within the animistic social ethos, people are not allowed to pollute snow because it is the abode of fairies.

The animistic ethos had elaborate rules for water channels, trees, animals, wildlife, rivers, humans, meadows, harvesting, agriculture and hunting. These rules were deeply ingrained in the life world of communities inhabiting mountains of Gilgit-Baltistan.

Being a part of the symbolic order of things, people still express their subjective feelings and views about the objective world in the symbolic language derived from nature and cryosphere. Imtiaz Sheiki, a renowned Shina language poet, represents his feelings towards the beloved and his fears in metaphors and similes drawn from cryosphere. He says: ‘Tu aday bay nay nikha taatey sartaanaey suuri bay, Bazono hinaey shiri tadaq chal bileejamus’. Translation: (Never appear before me like that the scorching sun of summer, For I melt away like a snow of the spring before you warmth).

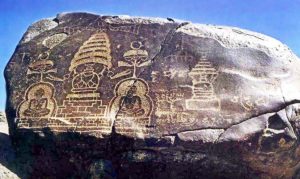

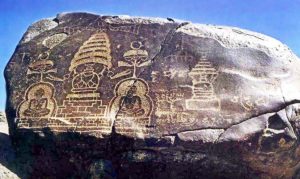

The connection between destruction of symbolic world and damage to cryosphere and nature is well illustrated by the case of Diamer district in Gilgit-Baltistan. Diamer is one of the oldest settlements in Gilgit-Baltistan with rich cultural history. The real name of famous Nanga Parbat mountain is Diamer, which means the abode of fairies.

It is derived from ancient Indic word ‘Devameru’ which means the sacred mountains of the deities. Interestingly, Germans named the meadow at the base of Nanga Parbat as fairy meadows. It is by inhaling smoke of juniper branches that shaman enters into ecstatic state. The animistic/shamanistic ethos prohibits cutting of juniper tree because it was said that fairies perch on these trees.

Also, hunting of ibex and other wildlife of certain age and size is prohibited because it is believed to be domesticated animal of fairies. Hunting is prohibited apart from designated sessions.

With the opening of Gilgit-Baltistan including Diamer through Karakoram Highway (KKH) and other developments after 1970s, people got exposure to market forces and exogenous lifestyle. It has brought about change in the animistic worldview.

Currently, out of 249205.159 hector of forest cover in Gilgit-Baltistan, 177324.4 are situated in Diamer region. Now situation is that the people have chopped most of the forests.

According to Climate Change Division, Pakistan, “Forest area in G-B has fallen to 295,000 from 640,000 hectares in the last 20 years due to callous cutting of trees and illegal transportation down-country."

Indigenous knowledge emerged from the fact that the people are humbled by the sheer power of nature. Famous mountaineer Ryan Hold Mesner deferred the idea of climbing Mt. Kailash after hearing stories from indigenous groups about its sacred and symbolic significance in local ethos.

It is an example of humbleness and submission to the symbolic and physical world of indigenous people. Today that kind of humbleness has become rare.

Technological advancement has enabled the sapient homo sapiens of today to subjugate nature. This has given birth to epistemological and cosmic hubris among the torch bearers of modern science and knowledge. With the conquest of nature by humans, we have entered into the age of Anthropocene.

After the de-mythologisation of their worldview, local communities in Gilgit-Baltistan are in a situation where they have lost the indigenous knowledge on the one hand, and lack modern knowledge to tackle challenges of climate change on the other.

After the de-mythologisation of their worldview, local communities in Gilgit-Baltistan are in a situation where they have lost the indigenous knowledge on the one hand, and lack modern knowledge to tackle challenges of climate change on the other.

By losing their symbolic world, they have lost their empathetic connection with nature. They are lost because, in the words of German poet Friedrich Hölderlin, it is “the time of the gods who have fled and of the god who is coming.”

Instead of animistic deities, a brutal god of market has arrived in the region. Today the communities of the water tower of the world do not have clean drinking water facility in their homes, but they receive bottled water delivered at their doorstep by multinational companies. It does not make them richer than their predecessors.

Actually, it means that they have become merely consumers with no symbolic attachment with they physical environ and human habitus.

The local communities in GB are increasingly facing the consequences of climate change in the shape of droughts, floods, tropical cyclones, wildfires, rising sea levels and melting glaciers. They have become really poor and vulnerable to these hazards because they have lost whatever knowledge and natural resources they had.

They are witnessing melting of glaciers right before their eyes. Since the whole edifice of symbolic world, material culture, identity and economy of Gilgit-Baltistan is literally based on cryosphere. It is melting under the effects of global warming.

It makes all that is solid and symbolic melt into thin air. The situation is aggravated by the practices and production of modern knowledge about local conditions from purely scientific point of view. It results in the exclusion of human agency and indigenous knowledge. As a result, the status of humans has been reduced to facts and figures.

The nature of challenges and threats posed by glacier melt in the cryosphere of the Hindu Kush, the Karakoram and Himalaya regions and other parts of the world demands transdisciplinary and transboundary approach.

Unfortunately, the research and production of knowledge about global warming is done in silos of different disciplines. There is lack of communication and dialogue among different disciplines.

Even if the research is scientifically valid, it is not communicated to the common.The yawing gap between the understanding of situation climate change by scientists and lack of realisation about it among the masses does not exist due to some intrinsic intellectual weakness of the commons, but by the huge difference between infrastructure of understanding available to scientists and social scientists.

It is ironic that while the glaciers are rapidly melting and trickling down to communities living near the glaciers and downstream, the knowledge about climate change is trickling up into the watertight compartments of disciplines.

The trouble with the prevalent technopolic approach is that in its attempt to rectify technological fallout, it invents new instruments to tackle the challenge. Hence, it creates infinite loop of technological application for problems by technology itself. The way we have organised our life support system today through technology needs to be revisited. No doubt science can provide solutions to the impending dangers to our planet, but it is unwise to expect absolute answers to questions about every problem under the sun.

It is important to combine human and scientific element in our approach to the challenges of climate change.

So far the institutional arrangements and discursive practices of modern knowledge have treated indigenous wisdom as primitive view unable to make sense of the world around it. The most important outcome of the forum on cryosphere and society is propounding of the idea of knowledge brokers. They will be people who will bridge the gap between social and natural sciences, and work as a conduit of knowledge between people and research.

This cannot be done unless technology is not democratised, and indigenous knowledge are included in global climate science and policy processes.

The participants of the forum on the cryosphere and society in Nepal realised the challenges in knowledge sharing. To overcome communication gap at interdisciplinary level, it has been proposed to initiate interdisciplinary dialogue for eclectic input and holistic vision for the mankind.

All the mountain communities of the Hindu Kush, the Karakoram and Himalayan region are on the peripheries of power dispensation, cultural capital and knowledge centres. Therefore, they had to rely on exogenous power centres for knowledge, decisions and policies regarding their future.

To restore agency among the marginalised communities of mountains and enable them to take charge of their own fate, it is imperative to establish knowledge centres and make them part of power dispensation. It will enable researchers and policy makers to accommodate indigenous wisdom in planning and production respectively of about climate change.

The world entered into the twentieth century with the belief that science and disenchanted worldview of rationality would usher humanity into a new era of peace, leisure, prosperity and progress. It was hoped that the scientific progress would end the miseries and sufferings that humans faced since the time immemorial in their interaction with nature.

In the historical shift brought about by industrial revolution, the train, telegraph, telephone and electricity were just a prologue of the brave new world. Since then, mankind has been witnessing the ever-increasing miracles of technology and its impact on society and the world.

However, the world started to realise unintended consequences of unbridled passion to turn everything and entity into resource and modern penchant for innovation on the very life support system of our planet.

At the turn of the twentieth century, we rejoiced at the disenchantment of our world by rational élan of modernity. What we do not realise today is that humans are undergoing a process of second disenchantment. However, this time it is disenchantment from the disenchanted world of instrumental rationality. The consequences of instrumentalisation of the natural world and life world appear in the shape of existential threat to the planet by environmental degradation and climate change.

To ward off the threats emanating from warming of our globe, it is indispensable to bring the world together to view global warming as a collective threat for all the living beings on the planet.

To reflect upon issues and challenges pertaining to climate change, the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) arranged the ‘International Forum on the Cryosphere and Society: The Voice of the HKH’ from 28-30 August 2019, in Kathmandu, Nepal.

The main objective of the forum was to bring together regional and international experts and stakeholders to establish a better understanding of the framework of cryosphere and explore the links between the cryosphere and communities inhabiting mountains and downstream regions.

In the forum, key scientists from the region, the international scientific community, social scientists, community representatives, different user groups and decision-makers came together and established a dialogue about the cryosphere, its role and its importance for the society of the Hindu Kush-Himalaya region (HKH). They explored different themes related to the cryosphere and society.

Although the conference provided an excellent opportunity for relevant people to reflect upon the issue of cryosphere and society from multiple angles, the scientific perspective remained dominant. However, an interactive session on ‘Cryosphere contribution to spiritual, symbolic, cultural, and religious perceptions’ provided interesting insights into relationship between crises in the symbolic world and global warming.

To demonstrate the validity of this claim, it is better to provide a case study of a society whose symbolic world, life world, identity, cultural metaphors and material culture are all shaped by cryosphere.

In Pakistan, Gilgit-Baltistan forms a cryosphere that benefit inhabitants of mountainous region and downstream communities. It is near Gilgit town where the mighty massifs of the Karakoram, the Hindu Kush and Himalaya meet. Together with Pamir, Kunlun Shan, Tien Shan mountain ranges, the whole region spanning from the Hindu Kush to Himalaya forms the water tower of Asia.

Given the cryospheric characteristics of local culture, it can be said that through human interaction with cryosphere and geography, the culture and symbolic world of Gilgit-Baltistan has been formed. It is visible in its animistic worldview and indigenous knowledge.

A salient feature of this worldview is that there is no dichotomy between human and nature in its cosmological order; rather it treats human as a part of the bigger whole called nature. This animistic framework of mind infused symbolic meaning and vitality to the things both animate and inanimate.

That is why juniper and willow trees, snow clad mountains, mighty boulders, brooks, meadows, and lakes are suffused with symbolic meaning. It is this symbolic order and its relationship with nature that saved the natural world from blatant human interference.

In the traditional animistic/shamanistic cosmology of Gilgit-Baltistan, human beings stand in the middle between pure beings of fairies and deities above and evil beings below. In traditional cosmology, different deities and fairies inform their mundane and metaphysical affairs. Interestingly, all the deities in local cosmology of Gilgit-Baltistan are women who inform the vision of the shaman who guides people regarding their relationship with nature and their conduct in society.

Within the animistic social ethos, people are not allowed to pollute snow because it is the abode of fairies.

The animistic ethos had elaborate rules for water channels, trees, animals, wildlife, rivers, humans, meadows, harvesting, agriculture and hunting. These rules were deeply ingrained in the life world of communities inhabiting mountains of Gilgit-Baltistan.

Being a part of the symbolic order of things, people still express their subjective feelings and views about the objective world in the symbolic language derived from nature and cryosphere. Imtiaz Sheiki, a renowned Shina language poet, represents his feelings towards the beloved and his fears in metaphors and similes drawn from cryosphere. He says: ‘Tu aday bay nay nikha taatey sartaanaey suuri bay, Bazono hinaey shiri tadaq chal bileejamus’. Translation: (Never appear before me like that the scorching sun of summer, For I melt away like a snow of the spring before you warmth).

The connection between destruction of symbolic world and damage to cryosphere and nature is well illustrated by the case of Diamer district in Gilgit-Baltistan. Diamer is one of the oldest settlements in Gilgit-Baltistan with rich cultural history. The real name of famous Nanga Parbat mountain is Diamer, which means the abode of fairies.

It is derived from ancient Indic word ‘Devameru’ which means the sacred mountains of the deities. Interestingly, Germans named the meadow at the base of Nanga Parbat as fairy meadows. It is by inhaling smoke of juniper branches that shaman enters into ecstatic state. The animistic/shamanistic ethos prohibits cutting of juniper tree because it was said that fairies perch on these trees.

Also, hunting of ibex and other wildlife of certain age and size is prohibited because it is believed to be domesticated animal of fairies. Hunting is prohibited apart from designated sessions.

With the opening of Gilgit-Baltistan including Diamer through Karakoram Highway (KKH) and other developments after 1970s, people got exposure to market forces and exogenous lifestyle. It has brought about change in the animistic worldview.

Currently, out of 249205.159 hector of forest cover in Gilgit-Baltistan, 177324.4 are situated in Diamer region. Now situation is that the people have chopped most of the forests.

According to Climate Change Division, Pakistan, “Forest area in G-B has fallen to 295,000 from 640,000 hectares in the last 20 years due to callous cutting of trees and illegal transportation down-country."

Indigenous knowledge emerged from the fact that the people are humbled by the sheer power of nature. Famous mountaineer Ryan Hold Mesner deferred the idea of climbing Mt. Kailash after hearing stories from indigenous groups about its sacred and symbolic significance in local ethos.

It is an example of humbleness and submission to the symbolic and physical world of indigenous people. Today that kind of humbleness has become rare.

Technological advancement has enabled the sapient homo sapiens of today to subjugate nature. This has given birth to epistemological and cosmic hubris among the torch bearers of modern science and knowledge. With the conquest of nature by humans, we have entered into the age of Anthropocene.

After the de-mythologisation of their worldview, local communities in Gilgit-Baltistan are in a situation where they have lost the indigenous knowledge on the one hand, and lack modern knowledge to tackle challenges of climate change on the other.

After the de-mythologisation of their worldview, local communities in Gilgit-Baltistan are in a situation where they have lost the indigenous knowledge on the one hand, and lack modern knowledge to tackle challenges of climate change on the other.By losing their symbolic world, they have lost their empathetic connection with nature. They are lost because, in the words of German poet Friedrich Hölderlin, it is “the time of the gods who have fled and of the god who is coming.”

Instead of animistic deities, a brutal god of market has arrived in the region. Today the communities of the water tower of the world do not have clean drinking water facility in their homes, but they receive bottled water delivered at their doorstep by multinational companies. It does not make them richer than their predecessors.

Actually, it means that they have become merely consumers with no symbolic attachment with they physical environ and human habitus.

The local communities in GB are increasingly facing the consequences of climate change in the shape of droughts, floods, tropical cyclones, wildfires, rising sea levels and melting glaciers. They have become really poor and vulnerable to these hazards because they have lost whatever knowledge and natural resources they had.

They are witnessing melting of glaciers right before their eyes. Since the whole edifice of symbolic world, material culture, identity and economy of Gilgit-Baltistan is literally based on cryosphere. It is melting under the effects of global warming.

It makes all that is solid and symbolic melt into thin air. The situation is aggravated by the practices and production of modern knowledge about local conditions from purely scientific point of view. It results in the exclusion of human agency and indigenous knowledge. As a result, the status of humans has been reduced to facts and figures.

The nature of challenges and threats posed by glacier melt in the cryosphere of the Hindu Kush, the Karakoram and Himalaya regions and other parts of the world demands transdisciplinary and transboundary approach.

Unfortunately, the research and production of knowledge about global warming is done in silos of different disciplines. There is lack of communication and dialogue among different disciplines.

Even if the research is scientifically valid, it is not communicated to the common.The yawing gap between the understanding of situation climate change by scientists and lack of realisation about it among the masses does not exist due to some intrinsic intellectual weakness of the commons, but by the huge difference between infrastructure of understanding available to scientists and social scientists.

It is ironic that while the glaciers are rapidly melting and trickling down to communities living near the glaciers and downstream, the knowledge about climate change is trickling up into the watertight compartments of disciplines.

The trouble with the prevalent technopolic approach is that in its attempt to rectify technological fallout, it invents new instruments to tackle the challenge. Hence, it creates infinite loop of technological application for problems by technology itself. The way we have organised our life support system today through technology needs to be revisited. No doubt science can provide solutions to the impending dangers to our planet, but it is unwise to expect absolute answers to questions about every problem under the sun.

It is important to combine human and scientific element in our approach to the challenges of climate change.

So far the institutional arrangements and discursive practices of modern knowledge have treated indigenous wisdom as primitive view unable to make sense of the world around it. The most important outcome of the forum on cryosphere and society is propounding of the idea of knowledge brokers. They will be people who will bridge the gap between social and natural sciences, and work as a conduit of knowledge between people and research.

This cannot be done unless technology is not democratised, and indigenous knowledge are included in global climate science and policy processes.

The participants of the forum on the cryosphere and society in Nepal realised the challenges in knowledge sharing. To overcome communication gap at interdisciplinary level, it has been proposed to initiate interdisciplinary dialogue for eclectic input and holistic vision for the mankind.

All the mountain communities of the Hindu Kush, the Karakoram and Himalayan region are on the peripheries of power dispensation, cultural capital and knowledge centres. Therefore, they had to rely on exogenous power centres for knowledge, decisions and policies regarding their future.

To restore agency among the marginalised communities of mountains and enable them to take charge of their own fate, it is imperative to establish knowledge centres and make them part of power dispensation. It will enable researchers and policy makers to accommodate indigenous wisdom in planning and production respectively of about climate change.