The fact that hazards are deeply embedded in social systems means that they are almost never democratic in their damage. They selectively hurt the weakest based on social class, gender, age and sometimes because of ethnicity. The Coronavirus pandemic is not going to be any different, argues Daanish Mustafa.

As a hazards geographer, I have always had difficulty with terms like natural hazards, mother nature, acts of God and so on. Today we are confronted with another one of the so called ‘natural’ calamities, the Coronavirus pandemic. As I write these lines, my parents and myself are in a state of lockdown with full social distancing protocols in place. As I went out for a final set of errands, I noticed more intensely the day labourers in Car Chowk near the tony suburb of Bahria Town in Pindi, as usual waiting for a day’s work. They still waited at noon, to earn to feed themselves and their families.

And it got me thinking how fortunate and callous I am to be able to afford myself the necessary luxury of social distancing, which is not an option for those in Car Chowk. Their constant labour is their only link to life and all it has to offer, come rain, sunshine, heat wave or Corona. I withdraw from the society that affords me the social privilege of withdrawal, but not to those in Car Chowk. How natural really is this new hazard? And how democratic is it going to be?

The answer to the first question, I suspect is the same that us hazards geographers have come to recognise with other more conventional hazards: floods, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, cyclones, etc. There’s nothing natural about this hazard. The COVID-19 (the apparent scientific name of the CoronaVirus), its hazardousness, and who it hurts, is as embedded in how human societies have produced themselves, as all the other more recognisable hazards.

A standard definition of hazards is that it happens when an environmental extreme comes into contact with a vulnerable population. Vulnerability is defined as susceptibility to suffer harm and the relative inability to recover from that harm. A tsunami on the coast of Antarctica might be a curious phenomena, perhaps even a spectacular one for the penguins. The same intensity tsunami on the coast of Karachi, however, could be a major disaster. The physical event, by itself, is not the hazard. It is the humans and how they interact with the event that creates the hazard.

Before the agricultural revolution, when human beings settled down, they started building permanent habitations, earthquakes were not a hazard. No one has ever been hurt by shaking ground. In fact, some people go to great lengths and expense (through drugs and alcohol) to make it shake, when it is not. It is when the buildings that we build, come crashing down over our heads that we have a hazard or a disaster at hand. We have to make peace with the painful realiszation, it is not mother nature, it never is - it is us.

Coronavirus has evolved from bats. There is some speculation on part of researchers that there may have been an intermediate carrier of the virus besides bats which infected the first humans at the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan, China.

The intermediate animal could have been snakes or pangolins. Both are legal and illegal parts of the Chinese diet, respectively. The latter for its medicinal qualities in the Chinese medical tradition. Regardless of the intermediate animal, it is robust science that bats are hosts of fairly virulent viruses, that bats’ robust immune systems have a capacity to negotiate, but other animals, such as humans’ less responsive immune systems, do not. When bat habitats are disturbed, they get stressed and are more likely to shed such viruses in their saliva, urine and feces, which can infect other animals. This simple insight is a stark reminder that humans’ arrogant exercise of their power against the non-human world is not without consequences. Coronavirus pandemic is one such consequence.

The fact that hazards are deeply embedded in social systems also means that they are almost never democratic in their damage. As a wealth of academic literature has amply demonstrated in the past, including through my own work on floods in Punjab and Rawalpindi-Islamabad, the apparently blind flood seems to selectively hurt the weakest based on social class, gender, age and sometimes because of ethnicity. For those of the readers who frequent the posh Jinnah Super Market in Islamabad, a look towards the south side of the School Road in F7/4, should give them the panoramic view of the informal France Colony inhabited by the Christian sanitary workers of Islamabad. Their location right by the Saidpur Kas, tributary of the Lai River in Rawalpindi, is not coincidental. Neither is their consequent inundation during seasonal flood season.

The reality of their geography, poverty, and marginality is deeply intertwined with the unjust matrix of contemporary Pakistani society. The Coronavirus pandemic is not going to be any different.

Coronavirus has probably already infected orders of magnitude more Pakistanis on March 14th, 2020, than the official figure of a few dozen infections would betray. In fact, according to Tomas Pueyo, the author of a credible viral article on the Corona pandemic, a death today from Coronavirus, given the known doubling rate of the infection and the length of time it takes from infection to death, means that there are 800 true (in fact) Coronavirus cases on that day. In Pakistan we are fortunate to not have had a death yet. But we have 53 confirmed cases and 76 suspected ones. The upshot is that we do not know the extent of the infection, and it is almost certainly worse than we know.

And no, the Hazara community in Quetta is not the main carrier of it, as a disgusting racist notification, dated 13/03/2020 from Managing Director, WASA, Quetta would suggest.

Like any hazard, the steps for a safety and security against the Coronavirus pandemic can be summarised as follows:

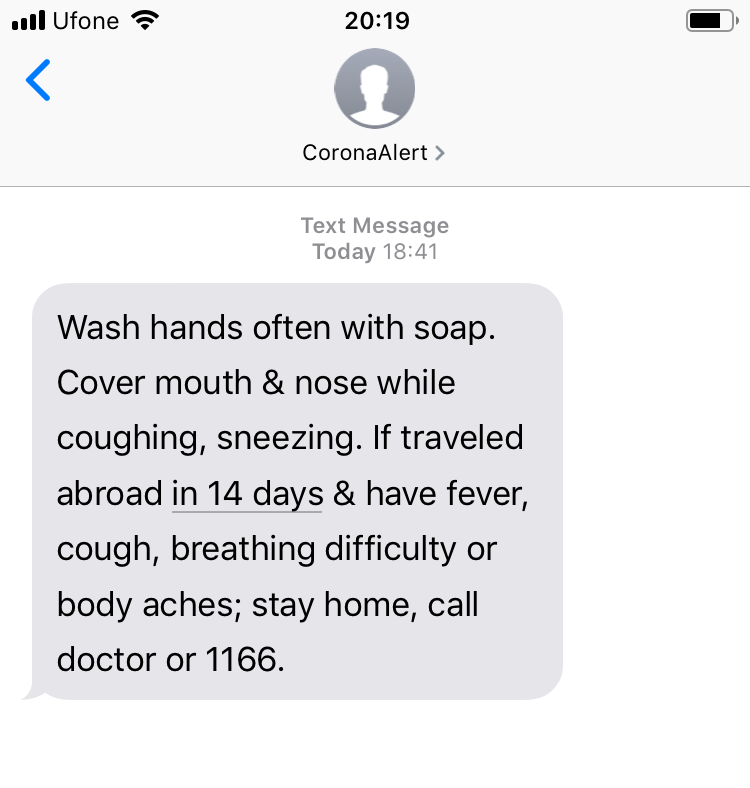

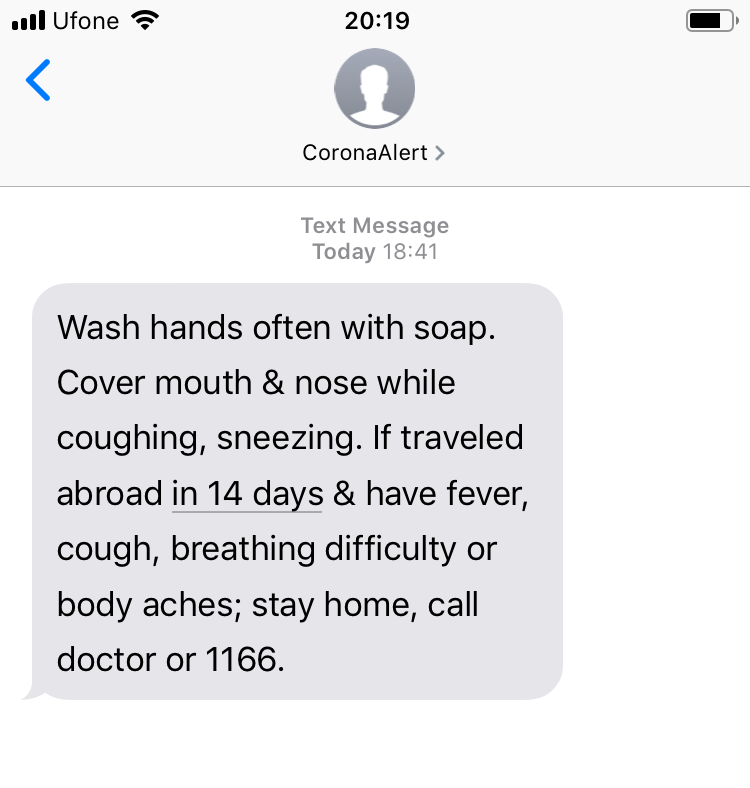

As for the risk knowledge, the screen shot above of the message received from the government on my mobile as I write this article speaks volumes. It is in English! Not Urdu, not Punjabi, not Sindhi, not Shina, Pashto or any of the languages spoken and understood by Pakistanis. It is for the benefits of elites like us, and perhaps an international audience. And also, to massage the ego of the state functionaries, that indeed they conduct their business in English, like ‘real’ educated people.

As for the risk knowledge, the screen shot above of the message received from the government on my mobile as I write this article speaks volumes. It is in English! Not Urdu, not Punjabi, not Sindhi, not Shina, Pashto or any of the languages spoken and understood by Pakistanis. It is for the benefits of elites like us, and perhaps an international audience. And also, to massage the ego of the state functionaries, that indeed they conduct their business in English, like ‘real’ educated people.

For risk monitoring, there’s a list of hospitals available here. Needless to say the urban bias is staggering and the vast rural areas remain underserved, as they are in many other spheres. One could also get tested privately, but that is likely to set one back by, anywhere from Rs 7500-10,000. Not a realistic option for our friends in Car Chowk.

For dissemination and communication, the murmurs from the state are inaudible to most. Again, as I write this article, I can hear fire crackers going off on another wedding in my neighbourhood. Also, see the photo above.

And finally, for response capacity we come back to Car Chowk. It is between practically starving through social distancing, or suffering an infection. The choices are stark and an impeachment of what Car Chowk says about us. It is not a counsel of despair, but a plea to empathise, organise, critique and struggle against the system that leaves fellow humans in Car Chowk, and the non-humans’ viruses in our lungs.

As a hazards geographer, I have always had difficulty with terms like natural hazards, mother nature, acts of God and so on. Today we are confronted with another one of the so called ‘natural’ calamities, the Coronavirus pandemic. As I write these lines, my parents and myself are in a state of lockdown with full social distancing protocols in place. As I went out for a final set of errands, I noticed more intensely the day labourers in Car Chowk near the tony suburb of Bahria Town in Pindi, as usual waiting for a day’s work. They still waited at noon, to earn to feed themselves and their families.

And it got me thinking how fortunate and callous I am to be able to afford myself the necessary luxury of social distancing, which is not an option for those in Car Chowk. Their constant labour is their only link to life and all it has to offer, come rain, sunshine, heat wave or Corona. I withdraw from the society that affords me the social privilege of withdrawal, but not to those in Car Chowk. How natural really is this new hazard? And how democratic is it going to be?

The answer to the first question, I suspect is the same that us hazards geographers have come to recognise with other more conventional hazards: floods, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, cyclones, etc. There’s nothing natural about this hazard. The COVID-19 (the apparent scientific name of the CoronaVirus), its hazardousness, and who it hurts, is as embedded in how human societies have produced themselves, as all the other more recognisable hazards.

A standard definition of hazards is that it happens when an environmental extreme comes into contact with a vulnerable population. Vulnerability is defined as susceptibility to suffer harm and the relative inability to recover from that harm. A tsunami on the coast of Antarctica might be a curious phenomena, perhaps even a spectacular one for the penguins. The same intensity tsunami on the coast of Karachi, however, could be a major disaster. The physical event, by itself, is not the hazard. It is the humans and how they interact with the event that creates the hazard.

Before the agricultural revolution, when human beings settled down, they started building permanent habitations, earthquakes were not a hazard. No one has ever been hurt by shaking ground. In fact, some people go to great lengths and expense (through drugs and alcohol) to make it shake, when it is not. It is when the buildings that we build, come crashing down over our heads that we have a hazard or a disaster at hand. We have to make peace with the painful realiszation, it is not mother nature, it never is - it is us.

Coronavirus has evolved from bats. There is some speculation on part of researchers that there may have been an intermediate carrier of the virus besides bats which infected the first humans at the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan, China.

The intermediate animal could have been snakes or pangolins. Both are legal and illegal parts of the Chinese diet, respectively. The latter for its medicinal qualities in the Chinese medical tradition. Regardless of the intermediate animal, it is robust science that bats are hosts of fairly virulent viruses, that bats’ robust immune systems have a capacity to negotiate, but other animals, such as humans’ less responsive immune systems, do not. When bat habitats are disturbed, they get stressed and are more likely to shed such viruses in their saliva, urine and feces, which can infect other animals. This simple insight is a stark reminder that humans’ arrogant exercise of their power against the non-human world is not without consequences. Coronavirus pandemic is one such consequence.

The fact that hazards are deeply embedded in social systems also means that they are almost never democratic in their damage. As a wealth of academic literature has amply demonstrated in the past, including through my own work on floods in Punjab and Rawalpindi-Islamabad, the apparently blind flood seems to selectively hurt the weakest based on social class, gender, age and sometimes because of ethnicity. For those of the readers who frequent the posh Jinnah Super Market in Islamabad, a look towards the south side of the School Road in F7/4, should give them the panoramic view of the informal France Colony inhabited by the Christian sanitary workers of Islamabad. Their location right by the Saidpur Kas, tributary of the Lai River in Rawalpindi, is not coincidental. Neither is their consequent inundation during seasonal flood season.

The reality of their geography, poverty, and marginality is deeply intertwined with the unjust matrix of contemporary Pakistani society. The Coronavirus pandemic is not going to be any different.

Coronavirus has probably already infected orders of magnitude more Pakistanis on March 14th, 2020, than the official figure of a few dozen infections would betray. In fact, according to Tomas Pueyo, the author of a credible viral article on the Corona pandemic, a death today from Coronavirus, given the known doubling rate of the infection and the length of time it takes from infection to death, means that there are 800 true (in fact) Coronavirus cases on that day. In Pakistan we are fortunate to not have had a death yet. But we have 53 confirmed cases and 76 suspected ones. The upshot is that we do not know the extent of the infection, and it is almost certainly worse than we know.

And no, the Hazara community in Quetta is not the main carrier of it, as a disgusting racist notification, dated 13/03/2020 from Managing Director, WASA, Quetta would suggest.

Like any hazard, the steps for a safety and security against the Coronavirus pandemic can be summarised as follows:

- Risk knowledge (Educating the public about the virus and hygiene).

- Risk monitoring (testing in case of Coronavirus pandemic)

- Dissemination and communication (dissemination of understandable warnings, and prior preparedness information, to those at risk)

- Risk response capacity (appropriate medical facilities, capacity for social distancing)

As for the risk knowledge, the screen shot above of the message received from the government on my mobile as I write this article speaks volumes. It is in English! Not Urdu, not Punjabi, not Sindhi, not Shina, Pashto or any of the languages spoken and understood by Pakistanis. It is for the benefits of elites like us, and perhaps an international audience. And also, to massage the ego of the state functionaries, that indeed they conduct their business in English, like ‘real’ educated people.

As for the risk knowledge, the screen shot above of the message received from the government on my mobile as I write this article speaks volumes. It is in English! Not Urdu, not Punjabi, not Sindhi, not Shina, Pashto or any of the languages spoken and understood by Pakistanis. It is for the benefits of elites like us, and perhaps an international audience. And also, to massage the ego of the state functionaries, that indeed they conduct their business in English, like ‘real’ educated people.For risk monitoring, there’s a list of hospitals available here. Needless to say the urban bias is staggering and the vast rural areas remain underserved, as they are in many other spheres. One could also get tested privately, but that is likely to set one back by, anywhere from Rs 7500-10,000. Not a realistic option for our friends in Car Chowk.

For dissemination and communication, the murmurs from the state are inaudible to most. Again, as I write this article, I can hear fire crackers going off on another wedding in my neighbourhood. Also, see the photo above.

And finally, for response capacity we come back to Car Chowk. It is between practically starving through social distancing, or suffering an infection. The choices are stark and an impeachment of what Car Chowk says about us. It is not a counsel of despair, but a plea to empathise, organise, critique and struggle against the system that leaves fellow humans in Car Chowk, and the non-humans’ viruses in our lungs.