In this essay Faisal Devji, a Professor of Indian History at University of Oxford responds to a paper by Venkat Dhulipala, author of Creating a New Medina: State Power, Islam, and the Quest for Pakistan in Late Colonial North India. Devji defends his arguments that he presented in his seminal study Muslim Zion: Pakistan as a Political Idea that explores the origins of Pakistan, comparing its birth in 1947 with that of Israel in 1948. Dhulipala’s book argues, citing the discourses of Muslim Ulama, that Pakistan was the culmination of popular imagination of a sovereign Islamic state – a new Medina. Devji is not too impressed. Dhulipala's paper can be accessed here: Revisiting Creating a New Medina Reflections on Fault lines of Partition Historiography

The Islamabad-based journal Islamic Studies has taken the unusual step of publishing an essay that I initially thought must be an academic spoof, adopting the form of a lengthy tirade thinly-veiled as a review article. In it the historian Venkat Dhulipala berates critics of his book, Creating a New Medina, for numerous scholarly as well as personal and political faults including making up facts.[1] I am surprised that a reputable journal should have published a piece of this nature, which lowers the standard of debate on Pakistan’s founding by reducing it to the kind of polemics more familiar among trolls on social media.

Also read: Midnight's furies

In my 2015 review of Dhulipala’s book, I had jokingly described the attention he lavished on Ayesha Jalal’s The Sole Spokesman as a perverse gesture of love.[2] Jalal’s book, after all, was published three decades ago, and in his view posed two questions about the Pakistan movement that had become stereotypes during its heyday. These had to do with whether Jinnah really wanted Pakistan, and if so, whether it was meant to be an Islamic state. Dhulipala’s book asked the same questions, but offered positive answers where Jalal had given them negative ones. Its aim was to turn a political debate into a religious one.

In my 2015 review of Dhulipala’s book, I had jokingly described the attention he lavished on Ayesha Jalal’s The Sole Spokesman as a perverse gesture of love.[2] Jalal’s book, after all, was published three decades ago, and in his view posed two questions about the Pakistan movement that had become stereotypes during its heyday. These had to do with whether Jinnah really wanted Pakistan, and if so, whether it was meant to be an Islamic state. Dhulipala’s book asked the same questions, but offered positive answers where Jalal had given them negative ones. Its aim was to turn a political debate into a religious one.

The book was saved from becoming a mirror-image of Jalal’s by his focus on the writings of some Deobandi clerics, for whose limited number he compensated by prolix summaries of their works. These men, he argued, had imagined Pakistan as a New Medina and successor to the Caliphate. Without adducing any evidence for their influence, as Barbara Metcalf noted in her review of his book, Dhulipala suggested that as religious figures they must somehow be more authentic in their representation of Muslim opinion than the leaders of the Muslim League, thus turning Pakistan into a theological entity.[3]

My own book, Muslim Zion, argued that like other minority movements, Pakistan emerged from a tradition of political thought that viewed the nation-state with suspicion, adopting federalist and internationalist visions of the future.[4] When these possibilities collapsed with the Second World War, the state Muslim nationalists turned to was defined by the rejection of historical and territorial identity as its foundations. Pakistan, I suggested, belonged to an Enlightenment rather than Romantic political genealogy, and was founded upon the repudiation of blood-and-soil belonging in an ‘artificial’ social contract.

I was gratified to note that in his response Dhulipala has transferred his affections from Ayesha Jalal’s work to my own. In this text of fifty-five pages, he invokes my name more than a hundred times, not counting all indirect references to me and my book. I am flattered by this attention. But since Dhulipala has poured his heart out about me in deeply personal terms, pronouncing upon my psychological state and political motives, I feel I owe him the courtesy of a few pages in response. As he has complained more than once about the difficulty of my writing, I have also ‘dumbed down’ my remarks for his benefit.

Contradiction

For the most part Dhulipala’s essay consists of a laundry-list of sometimes random and self-contradictory accusations. He begins and ends it with a plea for civil debate, while nevertheless accusing me of a long catalogue of sins, from an “aversion to facts” to “pompous and often impenetrable prose”, even suggesting that the argument of my book can be reduced to “a case of collective acid tripping”. All very civil, in other words, but why then dedicate forty of his fifty-five pages to such self-evident tripe? Some mysterious obsession seems to be at play.

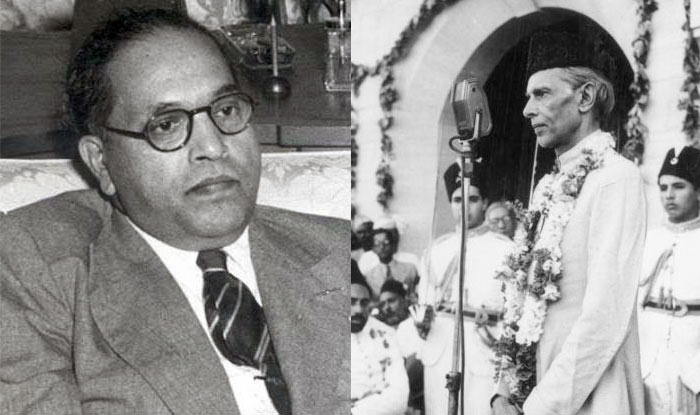

Having blamed me for ignoring Pakistan’s religious context in the Muslim world by lending it a falsely cosmopolitan history, Dhulipala dwells on Jinnah’s supposedly fascist influences from Europe. Dismissing attempts to derive Jinnah’s secularism from his dress and eating habits, he nevertheless sees the Quaid as a devout Muslim by virtue of occasionally donning Indian clothes similar to Nehru’s, and by rumours of his religious practices. I am accused of turning the low-caste leader Ambedkar into a “grubby bargainer”, only to have his alliance with Jinnah described as a “politics of convenience”.

My comparing the theme of a ‘New Medina’ with that of ‘Ramrajya’ leads to a mini-lecture on how Gandhi’s idea of the latter was inclusive. But so, by Dhulipala’s own account, was the Congress-supporting cleric Hussain Ahmad Madani’s notion of the former. My point, in any case, was to show that neither of these terms could be restricted to religious or secular points of view in either the Congress or the League. My statement that Pakistan, like the United States, did not set its foundation in some immemorial past, is refuted by mentioning Jinnah’s disapproval of its federalism in a non sequitur.

Describing how the country’s national narrative survived East Pakistan’s loss, because it was not territorially-grounded, leads to accusations of ignoring the “deep wound” of 1971. But surely trauma means the inability to process an experience? My claim that Pakistan was imagined with fluctuating borders, which may or may not have included Bengal, or the whole of its colonial territory along with that of Punjab, or a land corridor between East and West Pakistan, or the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, is taken to imply my denying Jinnah any territorial conception of Pakistan altogether.

Crime

Dhulipala charges me with “wild speculation” based on misrepresentations unworthy of a scholar. Such an accusation is more in keeping with his own prose, and expressed in a naïve or disingenuous reading of my argument. But this is the very thing he berates me for doing to his work, in what appears to be a defensive displacement of responsibility. Responsibility is key here, because Dhulipala’s concern with it is one that animates colonial history writing as well as that of its right-wing descendants. This way of writing conceives the past as a crime scene for which someone must be held accountable.

The crime, of course, is India’s violent Partition, for which the Muslim League is made responsible. My work must be linked to this original crime, whose responsibility Dhulipala thinks I am simply trying to conceal in what amounts to an ad hominem argument. Because he understands history as the record of a crime, Dhulipala dismisses my invocation of complexity, contingency and contradiction as mere evasions. Clearly, I must be part of a conspiracy to preserve the secular and liberal myth of Pakistan’s origins, which sets Dhulipala on a search for ulterior motives.

My intent is supposedly to exculpate the League by describing it as liberal and the Congress as fascist: “Devji insinuates that the Congress was a fascist party and that British appeasement of the Congress was akin to appeasement of the Nazis.” But I described the way in which all parties deployed the language of fascism and communism against each other while appropriating either—the most famous being Subhas Chandra Bose. He condemns my description of the League’s non-sectarianism by mentioning its exclusively Muslim membership. But I was only describing its refusal to entertain Muslim religious disputes.

These tendentious readings of my work are obsessional, with Dhulipala adopting the mirror-image of what he falsely considers my position in describing the League as fascist and Congress as liberal. He inveighs against Jinnah’s 1946 refusal to allow non-Muslims in Bengal and the Punjab to vote in the event of a plebiscite over Pakistan, describing it as “hardly the gesture of a constitutionalist, seeking a ‘social contract’”. Yet this only proves my point about Jinnah’s refusal to accept the defining role of territorial belonging, since he insisted that Hindus and Muslims constituted separate nations on other grounds.

As separate nations, Hindus and Muslims could not form a single electorate, but had to negotiate a contract on the basis of parity without any determining reference to demography. However convenient such a notion, which in the case of a plebiscite betrayed Jinnah’s uncertainty about which way the Muslim majority would vote, it suggests the political idea I explored in my book. Dhulipala, however, is interested not in ideas but responsibility, irrelevantly accusing me of absolving the British of blame in the Partition and ignoring Jinnah’s anti-democratic actions, as if assigning responsibility was ever my object.

Not content with trying to rescue the League in history, I am accused of translating its anti-Congress alliance with Dravidian and Dalit movements in the past into a Dalit-Muslim one for the present. We have left the realm of scholarship when Dhulipala says about me that “those wistful about the lost opportunity of an ethnic alliance against the Congress in colonial India are now pitching for a Dalit-Muslim alliance”. Except the article of mine he cites as evidence does exactly the opposite, arguing that a Dalit-Muslim alliance is impossible, and even that the ‘Muslim community’ cannot be a political actor in India.[5]

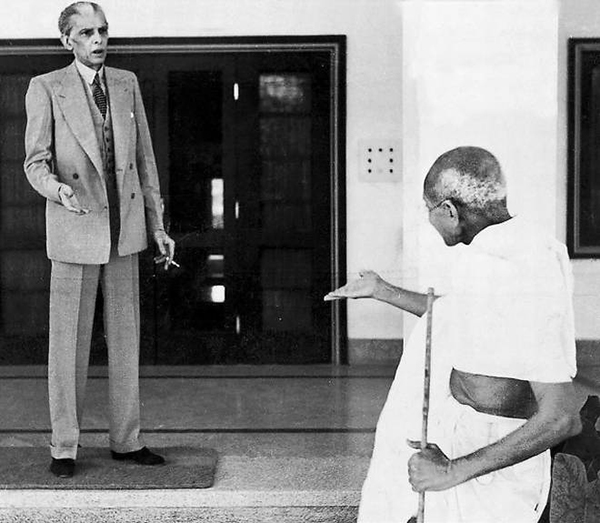

It is in such petty flights of fancy that Dhulipala becomes truly inventive, as when he describes Jinnah’s “stereotyping of Gandhi as the Bania, using it as a term of opprobrium and abuse similar to the use of the term Jew by the Nazis to connote a congenitally devious, scheming, lying, despicable or untrustworthy people”. Caricatures of the Bania were part of Indian common-sense, at the time as today, and hardly unique to Jinnah. Indeed, he took pleasure in describing himself, correctly as far as caste went, as the Bania’s Muslim equivalent, saying that he could speak to Gandhi as a Khoja would to a Bania.

Clerics

There is often something Pavlovian about archival historians, whose salivary glands are triggered by the very mention of unseen evidence—whatever its actual content might be. For them Dhulipala’s research on the obscure if not uninteresting treatises of some Deobandi writers promised to reveal a new world of religious thinking about Pakistan. Nothing could be more attractive in the post-9/11 world, where Islam has become a fascination grouping Muslim fundamentalists, Hindu nationalists and the alt-right in Europe and America into a kind of dysfunctional family.

But even the fascination with Islam cannot save Dhulipala’s account, for his evidence supports my argument more than it does his own. The ‘New Medina’ Dhulipala writes about is surely an example of my ‘Muslim Zion’, since it is premised upon the rejection of India’s own Muslim history and geography for an abstract utopia placed elsewhere in space and time. Rather than a traditional religious category, such a conception was a liberal or modernist, and later Islamist one, meant to re-imagine the future in a purely theoretical past of the kind familiar from a New Rome, New Athens or New Jerusalem.

Anyone familiar with how Medina is deployed as a theme, knows that like my ‘Muslim Zion’, it is premised upon ideas of migration to a new land. It doesn’t matter how many Muslims actually live in or move to its Pakistan, crucial instead being the very conception of hijrat or departure—with Pakistan itself seen as leaving India. Medina is also conceived in liberal rather than religious terms as the site of an ‘ancient constitution’, generally called the ‘Constitution of Medina’, and defined by the ‘social contract’ between different religious groups. Its adoption by the ulama signals the breakdown of their theological categories.

Unlike Medina, a utopia generally situated in Muhammad’s time, the Caliphate is seen as a post-prophetic institution. It represents an ideal dominated not by the relationship of different groups but the problem of legitimate authority. These are, in other words, distinct, even contradictory sites of social and political imagination, and cannot be lumped together as Dhulipala does. They also illustrate how the ulama can only frame their politics in modernist terms, as Muhammad Qasim Zaman argues in his recent book, Islam in Pakistan, but without therefore becoming liberals in the process.[6]

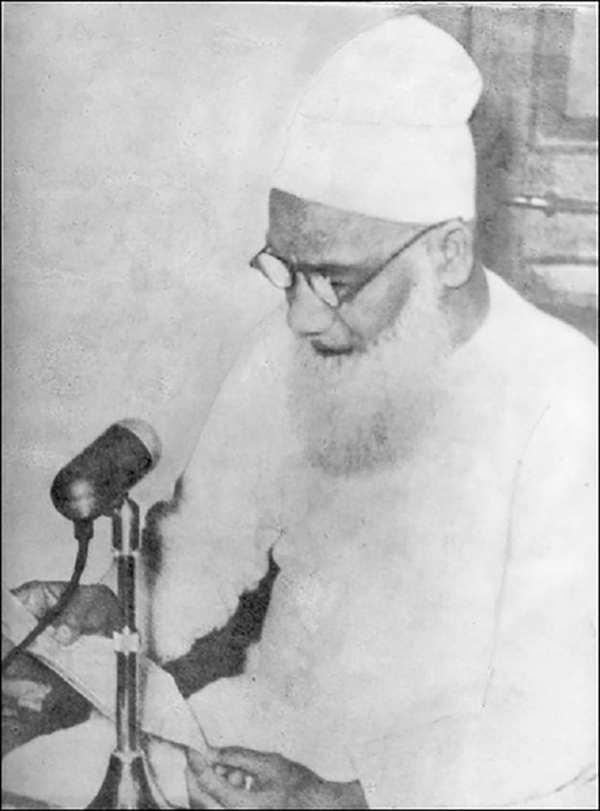

Dhulipala accuses me of denigrating religion, but the theological position I had dismissed belonged to him, not the ulama. In order to have them represent some authentic and alternative vision, he must sequester these men in the zenana of religion like so many concubines. Yet Dhulipala focuses not on their theological views but engagement with modernist categories, and can therefore offer us neither an alternative nor religious narrative for Pakistan. His chief example of a cleric who ‘imagined’ Pakistan as a New Medina, Shabbir Ahmad Usmani, only did so in 1946, hardly enough time to influence its creation.

Pakistan’s leading modernist scholar, Fazlur Rahman, noted decades ago that the ulama’s views paradoxically coincided with those of the secularists in their attempts to prevent the state taking possession of Islam.[7] He pointed out that in all three recensions of Pakistan’s constitution, it appears either as an item or a limitation without positive form. It was the modernists and Islamists who wanted to turn Islam into an expansive ideology, which they situated in a Cold War context by comparing it to communism. Such alliances and influences can neither be seen nor acknowledged in Dhulipala’s religious narrative.

Dhulipala’s fixation on the ulama’s importance and authenticity is misplaced. Both major groups of clerics, Barelwis and Deobandis, but also the Ahl-e Hadith, emerged in the 19th century alongside the modernists. They only came to have a significant influence in the areas that became Pakistan after its creation, by a migration of ideas and personnel to its ‘New Medina’. The only Islamic institutions that survive from pre-colonial times, dominating the countryside, are the Sufi shrines with which these ulama have an ambiguous relationship. No significant seminary or clerical tradition remains from that period.

If Dhulipala looked beyond theology, he would realise that my argument is confirmed by new research. Andrew Sartori’s archivally rich Liberalism in Empire, for instance, doesn’t mention my book, but makes a similar argument about the way in which the Pakistan movement gained traction in Bengal.[8] One site of its emergence, he writes, was as a ‘subaltern echo’ of settler colonialism in the Muslim agricultural colonisation of Assam. It was the colonial government’s attempt to hinder this movement into a new land that gave Pakistan political meaning as what I call a ‘Muslim Zion’.

If Dhulipala looked beyond theology, he would realise that my argument is confirmed by new research. Andrew Sartori’s archivally rich Liberalism in Empire, for instance, doesn’t mention my book, but makes a similar argument about the way in which the Pakistan movement gained traction in Bengal.[8] One site of its emergence, he writes, was as a ‘subaltern echo’ of settler colonialism in the Muslim agricultural colonisation of Assam. It was the colonial government’s attempt to hinder this movement into a new land that gave Pakistan political meaning as what I call a ‘Muslim Zion’.

Caste

Ambedkar plays a crucial role in Dhulipala’s argument, though his claim of being the first to take the Dalit leader’s views on Pakistan seriously is false, since I dealt with them fulsomely in Muslim Zion. But Ambedkar plays a curious part in Creating a New Medina, his anti-Hindu stance making his anti-Muslim views acceptable as the unbiased opinion of a third party. This role of neutral arbiter had characterised the colonial state, and Ambedkar adopted it on occasion. Today Ambedkar’s negative views on Islam, minus his intimate dealings with the Muslim League before 1940, are deployed by Hindu nationalists to claim him as one of their own.

Dhulipala sees my historicising of Ambedkar’s views on Islam as an effort to explain them away. He argues that if Ambedkar supported a state for Muslims in order to have Dalits take their place in India, as he tells us Jinnah thought, then why continue invoking anti-Muslim sentiments after Partition? But Ambedkar was disillusioned by independence, leaving Nehru’s cabinet, which, among other things, still valued Muslims more than Dalits. Anti-Muslim as I showed his views were, Ambedkar continued to follow some version of the Muslim League’s early political vision, including the abortive desire for a ‘Dalitsthan’.

Ambedkar’s primary focus was caste, yet Dhulipala omits this category from his analysis of the man’s work. How might we understand his changing views of Muslims after the 1940 Pakistan Resolution if we consider the role caste plays in them? Ambedkar’s political writing, for example, is about inserting caste into Indian debates as their principle of movement. Thus, in the essay “Ranade, Gandhi and Jinnah”, which Dhulipala cites, he argues that Hindu-Muslim conflict is not, in fact the primary one in India, with Gandhi and Jinnah opposed more by their personalities than politics, whose true motor is actually caste.[9]

He similarly inserts caste into history, arguing that Muslim invasions were directed less against Hindus than the Buddhists who had been reduced to Untouchables by the former. Hindus are seen as coming to terms with the invaders and surviving their rule better than the Buddhists, who had to deal with both Hindu and Muslim enemies. Yet they still preferred converting to Islam, even as Hinduism was transformed by its engagement with Buddhism into incorporating vegetarianism and idolatry. The point of all this was to make Dalits, and Buddhism as their ideological vehicle, central to Indian history and politics.[10]

Muslim Zion is the first study of Pakistan’s founding that takes caste seriously, not least because the Muslim League was the first party in India to advocate the electoral separation of low castes from Hinduism. Self-serving as this move was, it heralded the institutional form Dalit politics would take. But caste is also capable of fragmenting the Muslim community, so taking my cue from Ambedkar rather than weaponizing him as Dhulipala does, I use caste to break through the historiography’s communal categories. This new kind of narrative is what his return to the past and its dead debates denies.

Concupiscence

At first glance, and in keeping with his view of the past as a crime-scene, Dhulipala’s essay looks like the argument of a lawyer deploying selective quotation and undue inference to make his case. But upon closer inspection, it turns out to be more like the frenzy of a lover’s quarrel, with the aggrieved party throwing anything that comes to hand at a treacherous beloved without regard to shape, size or importance. This is why it is so difficult to deal with his accusations in conceptual terms. He also blames his critics for ignoring things that didn’t happen, in particular the Muslim League’s so-called ‘hostage theory’ of neighbourly relations and statements about the transfer of populations.

Also read: Frozen Tears – A Tale of Ruination and Human suffering devoid of Humanism

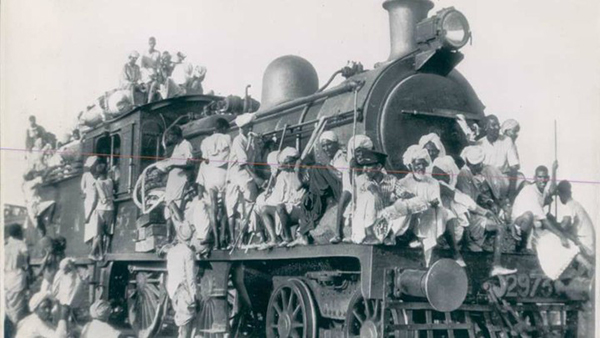

The hostage theory argued that the presence of Hindu or Muslim minorities in either country would guarantee the protection of their coreligionists in the other. But the assumption that majorities cared for the fate of their minority populations elsewhere was quickly shown to be false, and so this ‘theory’ remained a dead letter. As for the transfer of populations, it is a major theme in Ambedkar’s book on Pakistan, as among Hindu nationalists, and was a demand made by Sikh leaders upon the Congress during Partition. The Transfer of Power papers show that Jinnah disdained it, and in fact repeatedly urged Hindus and Sikhs not to leave Pakistan—from where they were nonetheless expelled.

Instead of engaging my argument as a whole, Dhulipala contests it in bits and pieces. He only addresses my narrative in its entirety by conspiratorially attributing it to ulterior motives. This is an approach more appropriate to far-right polemics. I will not undertake the unpleasant task of inquiring into Dhulipala’s own motives. But I should note that for the conspiracy-theorist all contrary argument and evidence is discounted, because it must be understood as subterfuge, evasion and excuse. And yet Dhulipala is unable to propose an argument of his own, simply adopting the mirror-images of those he dislikes in a perverse gesture of love.

[1] Venkat Dhulipala, “Revisiting Creating a New Medina: Reflections on Fault-Lines of Partition Historiography”, Islamic Studies, 57: 1-2 (2018), pp. 45-101. See also Venkat Dhulipala, Creating a New Medina: State, Power, Islam and the Quest for Pakistan in Late Colonial India (Cambridge, 2014).

[2] Faisal Devji, “Young Fogeys: The Anachronism of New Scholarship on Pakistan,” review of Venkat Dhulipala’s A New Medina, The Wire, 4 October 2015 (http://thewire.in/2015/10/04/young-fogeys-the-anachronism-of-new-scholarship-on-pakistan-12265/). See also Ayesha Jalal, The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan (Cambridge, 1985).

[3] Barbara Metcalf, “Review of Creating a New Medina: State, Power, Islam and the Quest for Pakistan in Late Colonial India, by Venkat Dhulipala”, The Book Review, 39:6 (2015).

[4] Faisal Devji, Muslim Zion: Pakistan as a Political Idea (Harvard, 2013).

[5] Faisal Devji, “Is a Dalit-Muslim Alliance Possible?” The Hindu, Aug. 31, 2016 (http://m.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/is-a-dalitmuslim-alliance-possible/article9051240.ece)

[6] Muhammad Qasim Zaman, Islam in Pakistan: A History (Princeton, 2018).

[7] Fazlur Rahman, “Islam and the constitutional problem of Pakistan”, Studia Islamica, no. 32 (1970), pp. 275-287.

[8] Andrew Sartori, Liberalism in Empire: An Alternative History (California, 2014).

[9] B.R. Ambedkar, “Ranade, Gandhi and Jinnah”, in Vasant Moon (ed.), Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar, Writings and Speeches, vol. 1 (Bombay: Education Department, Government of Maharashtra, 1989), pp. 207-40.

[10] See, for instance, B.R. Ambedkar, “Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Ancient India”, in Vasant Moon (ed.), Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar, Writings and Speeches, vol. 3 (Bombay: Education Department, Government of Maharashtra, 1989).

The Islamabad-based journal Islamic Studies has taken the unusual step of publishing an essay that I initially thought must be an academic spoof, adopting the form of a lengthy tirade thinly-veiled as a review article. In it the historian Venkat Dhulipala berates critics of his book, Creating a New Medina, for numerous scholarly as well as personal and political faults including making up facts.[1] I am surprised that a reputable journal should have published a piece of this nature, which lowers the standard of debate on Pakistan’s founding by reducing it to the kind of polemics more familiar among trolls on social media.

Also read: Midnight's furies

In my 2015 review of Dhulipala’s book, I had jokingly described the attention he lavished on Ayesha Jalal’s The Sole Spokesman as a perverse gesture of love.[2] Jalal’s book, after all, was published three decades ago, and in his view posed two questions about the Pakistan movement that had become stereotypes during its heyday. These had to do with whether Jinnah really wanted Pakistan, and if so, whether it was meant to be an Islamic state. Dhulipala’s book asked the same questions, but offered positive answers where Jalal had given them negative ones. Its aim was to turn a political debate into a religious one.

In my 2015 review of Dhulipala’s book, I had jokingly described the attention he lavished on Ayesha Jalal’s The Sole Spokesman as a perverse gesture of love.[2] Jalal’s book, after all, was published three decades ago, and in his view posed two questions about the Pakistan movement that had become stereotypes during its heyday. These had to do with whether Jinnah really wanted Pakistan, and if so, whether it was meant to be an Islamic state. Dhulipala’s book asked the same questions, but offered positive answers where Jalal had given them negative ones. Its aim was to turn a political debate into a religious one.The book was saved from becoming a mirror-image of Jalal’s by his focus on the writings of some Deobandi clerics, for whose limited number he compensated by prolix summaries of their works. These men, he argued, had imagined Pakistan as a New Medina and successor to the Caliphate. Without adducing any evidence for their influence, as Barbara Metcalf noted in her review of his book, Dhulipala suggested that as religious figures they must somehow be more authentic in their representation of Muslim opinion than the leaders of the Muslim League, thus turning Pakistan into a theological entity.[3]

My own book, Muslim Zion, argued that like other minority movements, Pakistan emerged from a tradition of political thought that viewed the nation-state with suspicion, adopting federalist and internationalist visions of the future.[4] When these possibilities collapsed with the Second World War, the state Muslim nationalists turned to was defined by the rejection of historical and territorial identity as its foundations. Pakistan, I suggested, belonged to an Enlightenment rather than Romantic political genealogy, and was founded upon the repudiation of blood-and-soil belonging in an ‘artificial’ social contract.

I was gratified to note that in his response Dhulipala has transferred his affections from Ayesha Jalal’s work to my own. In this text of fifty-five pages, he invokes my name more than a hundred times, not counting all indirect references to me and my book. I am flattered by this attention. But since Dhulipala has poured his heart out about me in deeply personal terms, pronouncing upon my psychological state and political motives, I feel I owe him the courtesy of a few pages in response. As he has complained more than once about the difficulty of my writing, I have also ‘dumbed down’ my remarks for his benefit.

Contradiction

For the most part Dhulipala’s essay consists of a laundry-list of sometimes random and self-contradictory accusations. He begins and ends it with a plea for civil debate, while nevertheless accusing me of a long catalogue of sins, from an “aversion to facts” to “pompous and often impenetrable prose”, even suggesting that the argument of my book can be reduced to “a case of collective acid tripping”. All very civil, in other words, but why then dedicate forty of his fifty-five pages to such self-evident tripe? Some mysterious obsession seems to be at play.

Having blamed me for ignoring Pakistan’s religious context in the Muslim world by lending it a falsely cosmopolitan history, Dhulipala dwells on Jinnah’s supposedly fascist influences from Europe. Dismissing attempts to derive Jinnah’s secularism from his dress and eating habits, he nevertheless sees the Quaid as a devout Muslim by virtue of occasionally donning Indian clothes similar to Nehru’s, and by rumours of his religious practices. I am accused of turning the low-caste leader Ambedkar into a “grubby bargainer”, only to have his alliance with Jinnah described as a “politics of convenience”.

My comparing the theme of a ‘New Medina’ with that of ‘Ramrajya’ leads to a mini-lecture on how Gandhi’s idea of the latter was inclusive. But so, by Dhulipala’s own account, was the Congress-supporting cleric Hussain Ahmad Madani’s notion of the former. My point, in any case, was to show that neither of these terms could be restricted to religious or secular points of view in either the Congress or the League. My statement that Pakistan, like the United States, did not set its foundation in some immemorial past, is refuted by mentioning Jinnah’s disapproval of its federalism in a non sequitur.

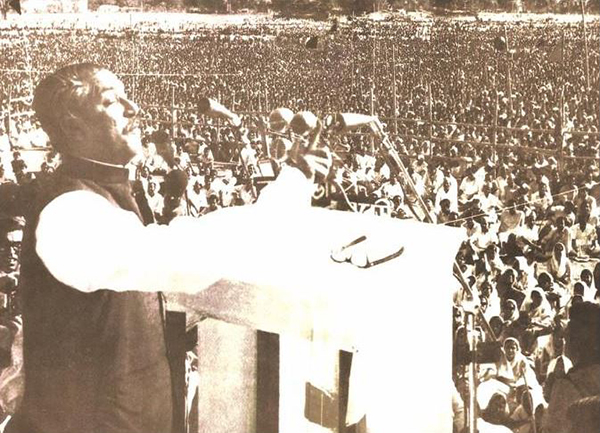

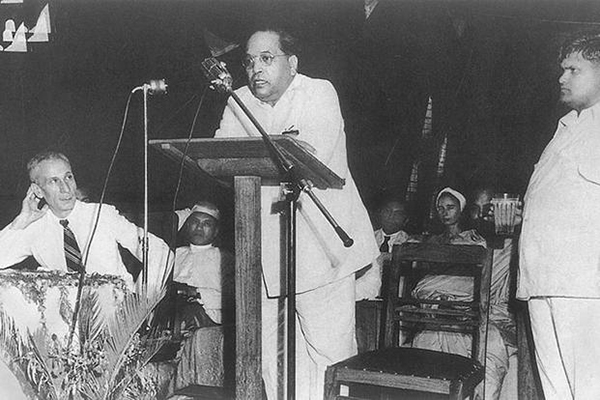

Sheikh Mujib, the founder of Bangladesh, addresses a gathering in Dhaka. Photo courtesy Defence.pk

My claim that Pakistan was imagined with fluctuating borders, which may or may not have included Bengal, or the whole of its colonial territory along with that of Punjab, or a land corridor between East and West Pakistan, or the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, is taken to imply my denying Jinnah any territorial conception of Pakistan altogether.

Describing how the country’s national narrative survived East Pakistan’s loss, because it was not territorially-grounded, leads to accusations of ignoring the “deep wound” of 1971. But surely trauma means the inability to process an experience? My claim that Pakistan was imagined with fluctuating borders, which may or may not have included Bengal, or the whole of its colonial territory along with that of Punjab, or a land corridor between East and West Pakistan, or the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, is taken to imply my denying Jinnah any territorial conception of Pakistan altogether.

Crime

Dhulipala charges me with “wild speculation” based on misrepresentations unworthy of a scholar. Such an accusation is more in keeping with his own prose, and expressed in a naïve or disingenuous reading of my argument. But this is the very thing he berates me for doing to his work, in what appears to be a defensive displacement of responsibility. Responsibility is key here, because Dhulipala’s concern with it is one that animates colonial history writing as well as that of its right-wing descendants. This way of writing conceives the past as a crime scene for which someone must be held accountable.

My intent is supposedly to exculpate the League by describing it as liberal and the Congress as fascist: “Devji insinuates that the Congress was a fascist party and that British appeasement of the Congress was akin to appeasement of the Nazis.” But I described the way in which all parties deployed the language of fascism and communism against each other while appropriating either—the most famous being Subhas Chandra Bose.

The crime, of course, is India’s violent Partition, for which the Muslim League is made responsible. My work must be linked to this original crime, whose responsibility Dhulipala thinks I am simply trying to conceal in what amounts to an ad hominem argument. Because he understands history as the record of a crime, Dhulipala dismisses my invocation of complexity, contingency and contradiction as mere evasions. Clearly, I must be part of a conspiracy to preserve the secular and liberal myth of Pakistan’s origins, which sets Dhulipala on a search for ulterior motives.

My intent is supposedly to exculpate the League by describing it as liberal and the Congress as fascist: “Devji insinuates that the Congress was a fascist party and that British appeasement of the Congress was akin to appeasement of the Nazis.” But I described the way in which all parties deployed the language of fascism and communism against each other while appropriating either—the most famous being Subhas Chandra Bose. He condemns my description of the League’s non-sectarianism by mentioning its exclusively Muslim membership. But I was only describing its refusal to entertain Muslim religious disputes.

Subhas Chandra Bose. Photo courtesy Edexlive

These tendentious readings of my work are obsessional, with Dhulipala adopting the mirror-image of what he falsely considers my position in describing the League as fascist and Congress as liberal. He inveighs against Jinnah’s 1946 refusal to allow non-Muslims in Bengal and the Punjab to vote in the event of a plebiscite over Pakistan, describing it as “hardly the gesture of a constitutionalist, seeking a ‘social contract’”. Yet this only proves my point about Jinnah’s refusal to accept the defining role of territorial belonging, since he insisted that Hindus and Muslims constituted separate nations on other grounds.

As separate nations, Hindus and Muslims could not form a single electorate, but had to negotiate a contract on the basis of parity without any determining reference to demography. However convenient such a notion, which in the case of a plebiscite betrayed Jinnah’s uncertainty about which way the Muslim majority would vote, it suggests the political idea I explored in my book. Dhulipala, however, is interested not in ideas but responsibility, irrelevantly accusing me of absolving the British of blame in the Partition and ignoring Jinnah’s anti-democratic actions, as if assigning responsibility was ever my object.

Picture courtesy India.com

Not content with trying to rescue the League in history, I am accused of translating its anti-Congress alliance with Dravidian and Dalit movements in the past into a Dalit-Muslim one for the present. We have left the realm of scholarship when Dhulipala says about me that “those wistful about the lost opportunity of an ethnic alliance against the Congress in colonial India are now pitching for a Dalit-Muslim alliance”. Except the article of mine he cites as evidence does exactly the opposite, arguing that a Dalit-Muslim alliance is impossible, and even that the ‘Muslim community’ cannot be a political actor in India.[5]

Caricatures of the Bania were part of Indian common-sense, at the time as today, and hardly unique to Jinnah. Indeed, he took pleasure in describing himself, correctly as far as caste went, as the Bania’s Muslim equivalent, saying that he could speak to Gandhi as a Khoja would to a Bania.

It is in such petty flights of fancy that Dhulipala becomes truly inventive, as when he describes Jinnah’s “stereotyping of Gandhi as the Bania, using it as a term of opprobrium and abuse similar to the use of the term Jew by the Nazis to connote a congenitally devious, scheming, lying, despicable or untrustworthy people”. Caricatures of the Bania were part of Indian common-sense, at the time as today, and hardly unique to Jinnah. Indeed, he took pleasure in describing himself, correctly as far as caste went, as the Bania’s Muslim equivalent, saying that he could speak to Gandhi as a Khoja would to a Bania.

Picture courtesy Express Tribune

Clerics

There is often something Pavlovian about archival historians, whose salivary glands are triggered by the very mention of unseen evidence—whatever its actual content might be. For them Dhulipala’s research on the obscure if not uninteresting treatises of some Deobandi writers promised to reveal a new world of religious thinking about Pakistan. Nothing could be more attractive in the post-9/11 world, where Islam has become a fascination grouping Muslim fundamentalists, Hindu nationalists and the alt-right in Europe and America into a kind of dysfunctional family.

But even the fascination with Islam cannot save Dhulipala’s account, for his evidence supports my argument more than it does his own. The ‘New Medina’ Dhulipala writes about is surely an example of my ‘Muslim Zion’, since it is premised upon the rejection of India’s own Muslim history and geography for an abstract utopia placed elsewhere in space and time. Rather than a traditional religious category, such a conception was a liberal or modernist, and later Islamist one, meant to re-imagine the future in a purely theoretical past of the kind familiar from a New Rome, New Athens or New Jerusalem.

Picture courtesy The Atlantic

Anyone familiar with how Medina is deployed as a theme, knows that like my ‘Muslim Zion’, it is premised upon ideas of migration to a new land. It doesn’t matter how many Muslims actually live in or move to its Pakistan, crucial instead being the very conception of hijrat or departure—with Pakistan itself seen as leaving India. Medina is also conceived in liberal rather than religious terms as the site of an ‘ancient constitution’, generally called the ‘Constitution of Medina’, and defined by the ‘social contract’ between different religious groups. Its adoption by the ulama signals the breakdown of their theological categories.

Unlike Medina, a utopia generally situated in Muhammad’s time, the Caliphate is seen as a post-prophetic institution. It represents an ideal dominated not by the relationship of different groups but the problem of legitimate authority. These are, in other words, distinct, even contradictory sites of social and political imagination, and cannot be lumped together as Dhulipala does. They also illustrate how the ulama can only frame their politics in modernist terms, as Muhammad Qasim Zaman argues in his recent book, Islam in Pakistan, but without therefore becoming liberals in the process.[6]

Dhulipala focuses not on their theological views but engagement with modernist categories, and can therefore offer us neither an alternative nor religious narrative for Pakistan. His chief example of a cleric who ‘imagined’ Pakistan as a New Medina, Shabbir Ahmad Usmani, only did so in 1946, hardly enough time to influence its creation.

Islamic scholar Shabbir Ahmad Usmani was instrumental in formulating theological arguments against the diatribes of the anti-Jinnah/AIML ulema.

Dhulipala accuses me of denigrating religion, but the theological position I had dismissed belonged to him, not the ulama. In order to have them represent some authentic and alternative vision, he must sequester these men in the zenana of religion like so many concubines. Yet Dhulipala focuses not on their theological views but engagement with modernist categories, and can therefore offer us neither an alternative nor religious narrative for Pakistan. His chief example of a cleric who ‘imagined’ Pakistan as a New Medina, Shabbir Ahmad Usmani, only did so in 1946, hardly enough time to influence its creation.

Dhulipala’s fixation on the ulama’s importance and authenticity is misplaced. Both major groups of clerics, Barelwis and Deobandis, but also the Ahl-e Hadith, emerged in the 19th century alongside the modernists. They only came to have a significant influence in the areas that became Pakistan after its creation, by a migration of ideas and personnel to its ‘New Medina’.

Pakistan’s leading modernist scholar, Fazlur Rahman, noted decades ago that the ulama’s views paradoxically coincided with those of the secularists in their attempts to prevent the state taking possession of Islam.[7] He pointed out that in all three recensions of Pakistan’s constitution, it appears either as an item or a limitation without positive form. It was the modernists and Islamists who wanted to turn Islam into an expansive ideology, which they situated in a Cold War context by comparing it to communism. Such alliances and influences can neither be seen nor acknowledged in Dhulipala’s religious narrative.

The only Islamic institutions that survive from pre-colonial times, dominating the countryside, are the Sufi shrines with which these ulama have an ambiguous relationship. No significant seminary or clerical tradition remains from that period.

Dhulipala’s fixation on the ulama’s importance and authenticity is misplaced. Both major groups of clerics, Barelwis and Deobandis, but also the Ahl-e Hadith, emerged in the 19th century alongside the modernists. They only came to have a significant influence in the areas that became Pakistan after its creation, by a migration of ideas and personnel to its ‘New Medina’. The only Islamic institutions that survive from pre-colonial times, dominating the countryside, are the Sufi shrines with which these ulama have an ambiguous relationship. No significant seminary or clerical tradition remains from that period.

If Dhulipala looked beyond theology, he would realise that my argument is confirmed by new research. Andrew Sartori’s archivally rich Liberalism in Empire, for instance, doesn’t mention my book, but makes a similar argument about the way in which the Pakistan movement gained traction in Bengal.[8] One site of its emergence, he writes, was as a ‘subaltern echo’ of settler colonialism in the Muslim agricultural colonisation of Assam. It was the colonial government’s attempt to hinder this movement into a new land that gave Pakistan political meaning as what I call a ‘Muslim Zion’.

If Dhulipala looked beyond theology, he would realise that my argument is confirmed by new research. Andrew Sartori’s archivally rich Liberalism in Empire, for instance, doesn’t mention my book, but makes a similar argument about the way in which the Pakistan movement gained traction in Bengal.[8] One site of its emergence, he writes, was as a ‘subaltern echo’ of settler colonialism in the Muslim agricultural colonisation of Assam. It was the colonial government’s attempt to hinder this movement into a new land that gave Pakistan political meaning as what I call a ‘Muslim Zion’.Caste

Ambedkar plays a crucial role in Dhulipala’s argument, though his claim of being the first to take the Dalit leader’s views on Pakistan seriously is false, since I dealt with them fulsomely in Muslim Zion. But Ambedkar plays a curious part in Creating a New Medina, his anti-Hindu stance making his anti-Muslim views acceptable as the unbiased opinion of a third party. This role of neutral arbiter had characterised the colonial state, and Ambedkar adopted it on occasion. Today Ambedkar’s negative views on Islam, minus his intimate dealings with the Muslim League before 1940, are deployed by Hindu nationalists to claim him as one of their own.

Dhulipala sees my historicising of Ambedkar’s views on Islam as an effort to explain them away. He argues that if Ambedkar supported a state for Muslims in order to have Dalits take their place in India, as he tells us Jinnah thought, then why continue invoking anti-Muslim sentiments after Partition? But Ambedkar was disillusioned by independence, leaving Nehru’s cabinet, which, among other things, still valued Muslims more than Dalits. Anti-Muslim as I showed his views were, Ambedkar continued to follow some version of the Muslim League’s early political vision, including the abortive desire for a ‘Dalitsthan’.

Dr Ambedkar. Picture courtesy: Countercurrents

In “Ranade, Gandhi and Jinnah”, Ambedkar argues that Hindu-Muslim conflict is not, in fact the primary one in India, with Gandhi and Jinnah opposed more by their personalities than politics, whose true motor is actually caste.

Ambedkar’s primary focus was caste, yet Dhulipala omits this category from his analysis of the man’s work. How might we understand his changing views of Muslims after the 1940 Pakistan Resolution if we consider the role caste plays in them? Ambedkar’s political writing, for example, is about inserting caste into Indian debates as their principle of movement. Thus, in the essay “Ranade, Gandhi and Jinnah”, which Dhulipala cites, he argues that Hindu-Muslim conflict is not, in fact the primary one in India, with Gandhi and Jinnah opposed more by their personalities than politics, whose true motor is actually caste.[9]

He similarly inserts caste into history, arguing that Muslim invasions were directed less against Hindus than the Buddhists who had been reduced to Untouchables by the former. Hindus are seen as coming to terms with the invaders and surviving their rule better than the Buddhists, who had to deal with both Hindu and Muslim enemies. Yet they still preferred converting to Islam, even as Hinduism was transformed by its engagement with Buddhism into incorporating vegetarianism and idolatry. The point of all this was to make Dalits, and Buddhism as their ideological vehicle, central to Indian history and politics.[10]

Muslim Zion is the first study of Pakistan’s founding that takes caste seriously, not least because the Muslim League was the first party in India to advocate the electoral separation of low castes from Hinduism. Self-serving as this move was, it heralded the institutional form Dalit politics would take. But caste is also capable of fragmenting the Muslim community, so taking my cue from Ambedkar rather than weaponizing him as Dhulipala does, I use caste to break through the historiography’s communal categories. This new kind of narrative is what his return to the past and its dead debates denies.

Concupiscence

At first glance, and in keeping with his view of the past as a crime-scene, Dhulipala’s essay looks like the argument of a lawyer deploying selective quotation and undue inference to make his case. But upon closer inspection, it turns out to be more like the frenzy of a lover’s quarrel, with the aggrieved party throwing anything that comes to hand at a treacherous beloved without regard to shape, size or importance. This is why it is so difficult to deal with his accusations in conceptual terms. He also blames his critics for ignoring things that didn’t happen, in particular the Muslim League’s so-called ‘hostage theory’ of neighbourly relations and statements about the transfer of populations.

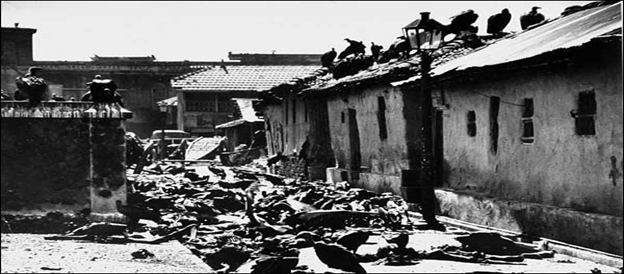

“The street was short and narrow. Lying like the garbage across the street and in its open gutters were bodies of the dead.”

Also read: Frozen Tears – A Tale of Ruination and Human suffering devoid of Humanism

The hostage theory argued that the presence of Hindu or Muslim minorities in either country would guarantee the protection of their coreligionists in the other. But the assumption that majorities cared for the fate of their minority populations elsewhere was quickly shown to be false, and so this ‘theory’ remained a dead letter. As for the transfer of populations, it is a major theme in Ambedkar’s book on Pakistan, as among Hindu nationalists, and was a demand made by Sikh leaders upon the Congress during Partition. The Transfer of Power papers show that Jinnah disdained it, and in fact repeatedly urged Hindus and Sikhs not to leave Pakistan—from where they were nonetheless expelled.

Instead of engaging my argument as a whole, Dhulipala contests it in bits and pieces. He only addresses my narrative in its entirety by conspiratorially attributing it to ulterior motives. This is an approach more appropriate to far-right polemics. I will not undertake the unpleasant task of inquiring into Dhulipala’s own motives. But I should note that for the conspiracy-theorist all contrary argument and evidence is discounted, because it must be understood as subterfuge, evasion and excuse. And yet Dhulipala is unable to propose an argument of his own, simply adopting the mirror-images of those he dislikes in a perverse gesture of love.

[1] Venkat Dhulipala, “Revisiting Creating a New Medina: Reflections on Fault-Lines of Partition Historiography”, Islamic Studies, 57: 1-2 (2018), pp. 45-101. See also Venkat Dhulipala, Creating a New Medina: State, Power, Islam and the Quest for Pakistan in Late Colonial India (Cambridge, 2014).

[2] Faisal Devji, “Young Fogeys: The Anachronism of New Scholarship on Pakistan,” review of Venkat Dhulipala’s A New Medina, The Wire, 4 October 2015 (http://thewire.in/2015/10/04/young-fogeys-the-anachronism-of-new-scholarship-on-pakistan-12265/). See also Ayesha Jalal, The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan (Cambridge, 1985).

[3] Barbara Metcalf, “Review of Creating a New Medina: State, Power, Islam and the Quest for Pakistan in Late Colonial India, by Venkat Dhulipala”, The Book Review, 39:6 (2015).

[4] Faisal Devji, Muslim Zion: Pakistan as a Political Idea (Harvard, 2013).

[5] Faisal Devji, “Is a Dalit-Muslim Alliance Possible?” The Hindu, Aug. 31, 2016 (http://m.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/is-a-dalitmuslim-alliance-possible/article9051240.ece)

[6] Muhammad Qasim Zaman, Islam in Pakistan: A History (Princeton, 2018).

[7] Fazlur Rahman, “Islam and the constitutional problem of Pakistan”, Studia Islamica, no. 32 (1970), pp. 275-287.

[8] Andrew Sartori, Liberalism in Empire: An Alternative History (California, 2014).

[9] B.R. Ambedkar, “Ranade, Gandhi and Jinnah”, in Vasant Moon (ed.), Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar, Writings and Speeches, vol. 1 (Bombay: Education Department, Government of Maharashtra, 1989), pp. 207-40.

[10] See, for instance, B.R. Ambedkar, “Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Ancient India”, in Vasant Moon (ed.), Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar, Writings and Speeches, vol. 3 (Bombay: Education Department, Government of Maharashtra, 1989).