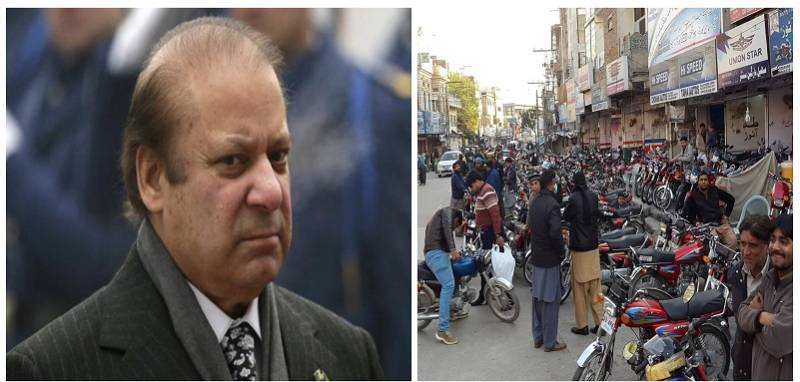

In olden times, some thinking political leader once opined that the last battle for the emancipation of Pakistan’s political system will be fought and led by Punjabi leadership. And now some of the political pundits are saying that the prophecy has come true—three time prime minister and discernible the most popular leader in heartland Punjab, Nawaz Sharif has announced that he would organize a campaign against those who have brought “this mad man (reference to Imran Khan) to power”. Nawaz Sharif in so many words has declared that he battle was not against Imran Khan, “As his battle is against those who installed him in Islamabad”—an obvious reference to military top brass. So is this going to be that proverbial last battle to which a sage Pakistani politician has made a reference in the past?

Cursory look at country’s history reveals the fact that the dominance of power structures by military and central bureaucracy has always been challenged by political leaders from the periphery—like Baloch nationalists challenged the dominance in 1970s, Sindhi leaders or those popular in rural Sindh challenged the dominance in 1980s. Those from urban Sindh got into a fight with the military in 1990s and Pashtun nationalists remained active in anti-establishment politics in a low key manner throughout this period. But none succeeded. One potent reason for their failure was that they always failed to mobilize Punjab.

Smaller traders and lower and middle classes in Punjabi cities mobilized in 1977 against the Bhutto regime and facilitated the military coup staged by General Zia-ul-Haq. In the intervening period, Punjab did mobilize for religious causes but quite paradoxically recognized only two popular leaders in electoral contests—Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif. Benazir Bhutto started losing her standing in Punjabi heartland after the 1996 dismissal of her government when she became a vocal and potent voice against the military's dominance of power structure.

Nawaz Sharif’s rise as an electoral success in Punjabi politics remained uninterrupted since 1980s. But he has never tested Punjabi waters as far as his capacity to mobilize Punjab middle classes—his mainstay in Punjab—for agitation politics.

At the conceptual level Nawaz Sharif’s idea of launching a protest movement in Punjabi heartland against military establishment—as in his own words his fight is not against Imran Khan, it was against those who brought Imran Khan to power—is problematic on account of two reasons. Firstly, Nawaz Sharif will be testing his popularity in a geographical area, where military and its top brass has traditionally held sway over the public opinion. The public opinion as reflected in the media and in the streets of Punjabi cities tend to be jingoistic in nature and content and generally perceive the military as their savior. The establishment has reinforced this traditional reflection of public opinions with the help of a vast propaganda machine that shows the military as a source of the country's strength and stability.

In this situation, Nawaz Sharif seems to be banking on the disenchantment of Punjabi middle classes with the existing political arrangement that has increased their economic hardships manifold during the past two years. Prices of essential goods are running amok and unemployment is rampant and as many businessmen in this part of the country are saying, the economy is in a state of recession. In this situation, Nawaz Sharif doesn’t need to ensure that each one of his followers believes what he believes. He only has to assemble thousands and thousands of them and deliver an anti-establishment speech in front of them.

Besides carefully drafted speeches, listing the success of governments and regimes hardly find an audience among middle classes in Punjab who are getting laid off in hundreds every day. So Nawaz Sharif has a relatively easy task ahead of him. A disgruntled political leader finds easy partners among middle classes, which are fast shrinking in strength and financial capacity.

However Nawaz Sharif’s clarion call for democracy is problematic from another perspective: suppose Nawaz Sharif succeeds in bringing thousands and thousands of his supporters to D-Chowk in January, as he plans to do in coming months. What then? Governments don’t fall if hundreds of thousands of people gather in front of their offices. Governments fall as a result of some kind of intervention. Traditionally this has been a model in Pakistani politics in the recent past: either the Supreme Court—in case of Yousaf Raza Gilani and Nawaz Sharif or the military and intelligence services—in case of Nawaz sharif only—intervened to send the government packing.

So will Nawaz Sharif demand some kind of intervention when his protest movement reaches maturity? If he does, it will be a total reversal of his stance. Ostensibly, he has been advocating stabilization of democratic institutions. And if Imran Khan’s government falls as a result of some kind of intervention, will it not cause embarrassment to Nawaz Sharif?

Confrontation and disruption of public life has in the past led to military intervention in the country. But more than intervention this protest movement will raise the question of integrity and unity of institutional structures of Pakistani state. Already the past six months have witnessed sensational rumors about a power struggle doing the rounds in Islamabad. Don’t forget that this will be an agitation movement launched from the heart of Punjab—house of Pakistani establishment. If Nawaz Sharif succeeds in mobilizing lower and middle classes of Central and Northern Punjab, we are in for turbulent times.

Cursory look at country’s history reveals the fact that the dominance of power structures by military and central bureaucracy has always been challenged by political leaders from the periphery—like Baloch nationalists challenged the dominance in 1970s, Sindhi leaders or those popular in rural Sindh challenged the dominance in 1980s. Those from urban Sindh got into a fight with the military in 1990s and Pashtun nationalists remained active in anti-establishment politics in a low key manner throughout this period. But none succeeded. One potent reason for their failure was that they always failed to mobilize Punjab.

Smaller traders and lower and middle classes in Punjabi cities mobilized in 1977 against the Bhutto regime and facilitated the military coup staged by General Zia-ul-Haq. In the intervening period, Punjab did mobilize for religious causes but quite paradoxically recognized only two popular leaders in electoral contests—Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif. Benazir Bhutto started losing her standing in Punjabi heartland after the 1996 dismissal of her government when she became a vocal and potent voice against the military's dominance of power structure.

Nawaz Sharif’s rise as an electoral success in Punjabi politics remained uninterrupted since 1980s. But he has never tested Punjabi waters as far as his capacity to mobilize Punjab middle classes—his mainstay in Punjab—for agitation politics.

At the conceptual level Nawaz Sharif’s idea of launching a protest movement in Punjabi heartland against military establishment—as in his own words his fight is not against Imran Khan, it was against those who brought Imran Khan to power—is problematic on account of two reasons. Firstly, Nawaz Sharif will be testing his popularity in a geographical area, where military and its top brass has traditionally held sway over the public opinion. The public opinion as reflected in the media and in the streets of Punjabi cities tend to be jingoistic in nature and content and generally perceive the military as their savior. The establishment has reinforced this traditional reflection of public opinions with the help of a vast propaganda machine that shows the military as a source of the country's strength and stability.

In this situation, Nawaz Sharif seems to be banking on the disenchantment of Punjabi middle classes with the existing political arrangement that has increased their economic hardships manifold during the past two years. Prices of essential goods are running amok and unemployment is rampant and as many businessmen in this part of the country are saying, the economy is in a state of recession. In this situation, Nawaz Sharif doesn’t need to ensure that each one of his followers believes what he believes. He only has to assemble thousands and thousands of them and deliver an anti-establishment speech in front of them.

Besides carefully drafted speeches, listing the success of governments and regimes hardly find an audience among middle classes in Punjab who are getting laid off in hundreds every day. So Nawaz Sharif has a relatively easy task ahead of him. A disgruntled political leader finds easy partners among middle classes, which are fast shrinking in strength and financial capacity.

However Nawaz Sharif’s clarion call for democracy is problematic from another perspective: suppose Nawaz Sharif succeeds in bringing thousands and thousands of his supporters to D-Chowk in January, as he plans to do in coming months. What then? Governments don’t fall if hundreds of thousands of people gather in front of their offices. Governments fall as a result of some kind of intervention. Traditionally this has been a model in Pakistani politics in the recent past: either the Supreme Court—in case of Yousaf Raza Gilani and Nawaz Sharif or the military and intelligence services—in case of Nawaz sharif only—intervened to send the government packing.

So will Nawaz Sharif demand some kind of intervention when his protest movement reaches maturity? If he does, it will be a total reversal of his stance. Ostensibly, he has been advocating stabilization of democratic institutions. And if Imran Khan’s government falls as a result of some kind of intervention, will it not cause embarrassment to Nawaz Sharif?

Confrontation and disruption of public life has in the past led to military intervention in the country. But more than intervention this protest movement will raise the question of integrity and unity of institutional structures of Pakistani state. Already the past six months have witnessed sensational rumors about a power struggle doing the rounds in Islamabad. Don’t forget that this will be an agitation movement launched from the heart of Punjab—house of Pakistani establishment. If Nawaz Sharif succeeds in mobilizing lower and middle classes of Central and Northern Punjab, we are in for turbulent times.