Nostalgia can definitely alleviate loneliness, enhance resilience and bolster creativity – as long as it’s a 'rational' sentimentality and not unfettered regret or sedentary, indolent procrastination

My friend, mentor, and not-too-distant relative Raza Rumi recently shared an article on nostalgia, authored by Jamie Bell for Big Think. The article, titled "Nostalgia triggers a reward pathway in our brains, according to science", is a succinct yet insightful read: it not only defines nostalgia and explains the historical evolution of the connotations attached to it, but also reviews neurological and psychological studies done on the impact nostalgia has on human beings. I have hyperlinked the article because you should definitely go and read it yourself – though I will still try to list the salient features (or that which I derived) from it hereunder:

My response to the article is simple: purely from my own personal experiences, nostalgia is indeed a powerful memory tool within our brain, and it also has many potential recuperative qualities. While I was asked to write an essay on it, I could definitely write a book about it – I'm sure by the end of this article, you might be able to see why.

In my opinion, there is definitely a lot of truth to what the article says about nostalgia – going beyond my individual experience, I would say that results of credible academic research by experts cannot and should not be refuted offhand. But, again, you should definitely read the article for yourself – and I would invite psychiatrists, psychologists, neurologists, and even philosophers, to comment on the nature of nostalgia and its impact on human beings and human life in general.

While we wait for the experts and intellectuals to further enlighten us on nostalgia, longing and wistfulness, let me share my own experiential perceptions with you. I used to be an information collector and hoarder – maybe I still am – but my understanding and constant practice of research techniques and methodologies, as well as forays into data analytics, allowed me to hone and polish myself professionally into an ‘intelligence analyst’: though that never really worked in my favour. Though I can obviously neither confirm nor deny anything, imputations that I belong or belonged to a mysterious world of ‘cloak and dagger’ is amusing at best, and excruciating at worst. So please allow me to digress.

Acquiring information, possessing knowledge, and fostering an understanding of concepts, issues and disciplines is really only the first step: one can only develop a meaningful comprehension, or obtain verifiable results, after gaining an insight into what information is useful and what isn’t, which knowledge is verifiably true and which is merely opinion or hearsay, and whether concepts can actually withstand robust testing in their theoretical validity as well as practical cogency – whether they intuitively ‘make sense’ and have any application in or relevance to real life, or not. According to prominent motivational speaker Dr. Joe Dispenza, “a memory without the emotional charge is called wisdom”; but as we all know, memories can’t be so easily dissociated from emotion. Not without the commensurate self-reflection and an inordinate – but not infinite – amount of cognitive discipline. Wisdom is the daughter of experience, with memory and emotion being two additional variables that each of us must contend with: not to overcome or master, but to find a balance within that gives us contentment.

Nostalgia isn’t as scientific or as controllable as the above processes. It occurs as a natural human instinct if not a reaction to environment, circumstances and / or emotions. In my opinion, nostalgia is more of an impulse than a reflex: reliving the past is easy, because you’ve already lived it once, and nostalgia allows you to do that again. There is nothing wrong with being sentimental about one’s own past, about one’s own perspectives and emotions regarding what is a lived experience, and therefore subjective in essence. Where that sentimentality becomes negative, even harmful, is when it is clouded by "what if" and "I should’ve" – nostalgia should invoke greater understanding if not unblemished happiness; it should not create lakes of regret for one to wallow in. One should fondly remember happy memories and the good times, and derive a greater understanding of one’s own self from the sad memories and tribulations. To avoid nostalgia becoming procrastination, there are two simple tools to use: always remember that sometimes you win, while at other times you learn; and it is infinitely wiser to plan for the future, even in tiny incremental steps, rather than just dreaming about a happier time that you ‘deserve’ or ‘hope to live’ in the future. But I will be the first to acknowledge that all that is easier said than done.

So my point is: nostalgia should be a positive sensation. If it only fills you with depression, remorse and regret, that is too much negative sentimentality that either invokes immense trauma, and is something that you are unable – or maybe psychosocially unwilling – to come to terms with. The emotive burden of regret will not let you learn anything. And if nostalgia of the past makes you dream incessantly about the future, if it makes you wish to recreate or prolong a good memory in a way that keeps you excessively stationary and leads you to excessively procrastinate, then you haven’t learned anything and you need to physically do something to make your dreams a reality. Make a list; compartmentalize your long-term goals into medium- and short-term steps; give yourself targets that are rational and achievable on a daily basis; make sure you are flexible and can adjust to the changes in circumstance and environment; always have alternates for your main plan; start small so that you have something big at the end; and most importantly, hope for the best, but always be prepared for the worst. Otherwise procrastination – which is essentially conjuring up dreams that have significant meaning but are not followed through with action – will destroy you.

How does nostalgia work for me? I would describe myself as imaginative instead of intelligent, as descriptive instead of verbose, and a researcher of reality forever teased by magic realism. The reason I told Raza I could write a book on the power of nostalgia, based on my own personal experiences – of life, memories, and reminiscence of longing as well as melancholy – is because I (sometimes literally) keep most if not all the receipts. Take it whichever way it suits you: maybe I’ve been brought up to always have to prove myself, or maybe I’ve always had to prove to myself that all of it was real and not just a vivid hallucination or a figment of my imagination. But I’m sure everyone can agree that the proof can speak for itself; beyond me presenting it, I acknowledge that everyone can have their own individual interpretation thereof, because everyone has a right to have their own opinion – call it what you want to. Acknowledgment does not necessarily have to be concession.

Now let me take you along on a ride through memories good and bad, times that made me happy and sad; since this is supposed to be about me and my nostalgia, I acknowledge the indispensable roles that others have performed in the episodes of my past which have fashioned and generated these memories, without necessarily lacerating old wounds for myself or anyone else. Yes, that means no love notes scribbled in books on politics and leadership.

While I reserve copyrights of the following for myself, I would be remiss to not give credit where it’s due: thank you to everyone who features in the memories I am about to present – I think they call it a ‘shout-out’ these days.

For the past fifteen years or so, I have been studying terrorism and extremism in addition to my research and work on political economy and factors affecting social mobilization (especially youth mobilization) in Pakistan. Sometimes it is hard for me to believe that I am in fact that old, but hey, Aaliyah Haughton said “age ain’t nothing but a number”, right? May she forever rest in peace.

Which reminds me: Jamie Bell also states in her article that music can trigger nostalgia. In that sense, I’d like to think I have a veritable jukebox inside my head. But one of my favourite lyrics – a phrase you might find across my social media – is from Queens of the Stone Age: “I want something good to die for, to make it beautiful to live”…

It’s only words, only words after all…

How do I know it’s been nearly fifteen years? Well, there used to be a publication at LUMS called ‘The Political Animal’. Published by the Law & Politics Society, or LPS, it contained contributions from students as well as professors on important political issues of the time. In 2008, I wrote an alarmist article titled “We are at war!”. I’ve been trying to find that issue – especially since it had a spoof Facebook profile of the-then Law Minister, Wasi Zafar, as a full page item on the back cover – but with no success as yet. Why did I write that? Maybe because I was an Assistant Editor of said magazine and just had to contribute something, or maybe I felt obliged to put in a pro-military but pessimistic viewpoint on the security situation of the country as it was at the time. Did it help? Maybe. Did it make me a good journalist? No. Did I learn my lesson? Of course not!

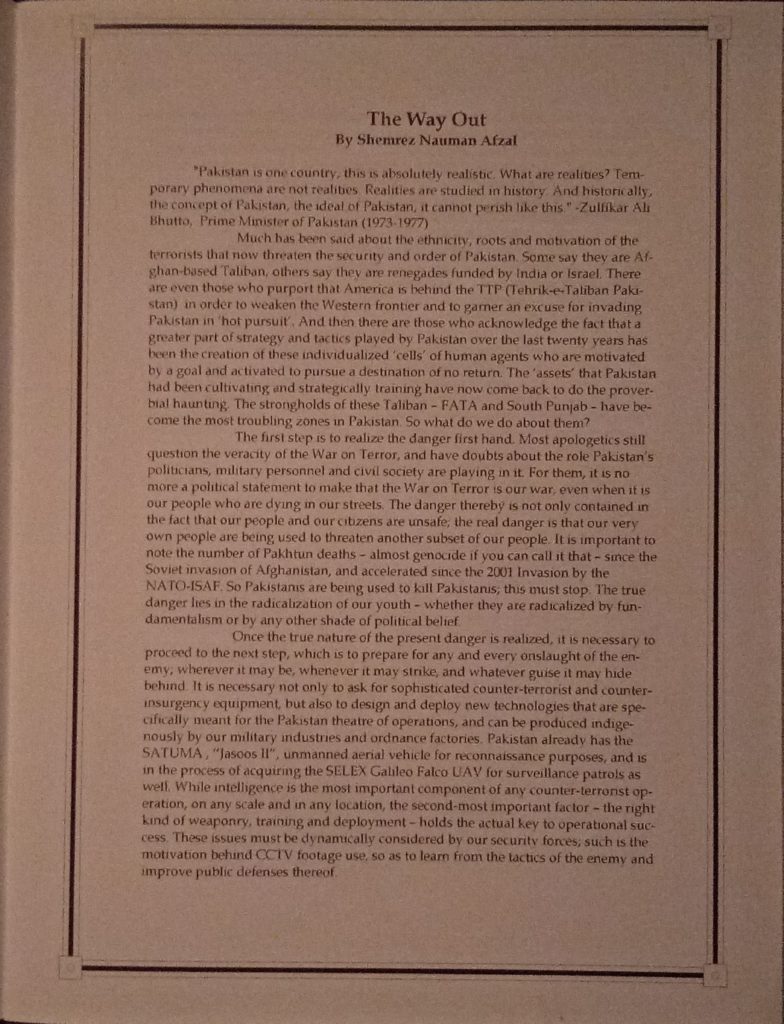

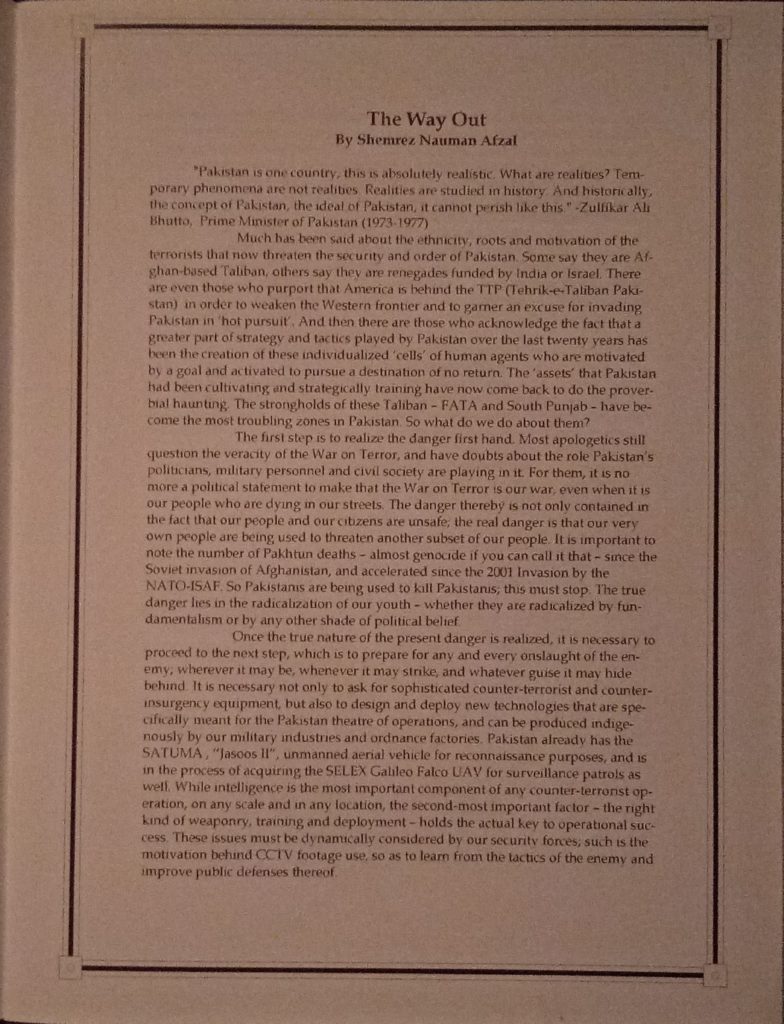

A year later, I wrote another article titled “The Way Out”. This time, the security situation was worse than before, and the military itself appeared ill-placed at best, or incapable at worst, to deal with its core mandate: national security. So I set about trying to rile up the people of Pakistan – the general citizenry, the common man, anyone who still had the ethos of ‘hum hain Pakistani, hum toh jeetenge, haan jeetenge’ – to come to their senses, come to grips with how extremist militants had begun using Islam to terrorize Muslims and other Pakistanis, and at least come together to agree on some basic principles if not figure out a way to comprehensively deal with the twin menace of extremism and terrorism.

Yes, I said the true danger lies in the radicalization of the Pakistani youth. Yes, I said our ‘strategic assets’ had come back to haunt us. Yes, I called out the Pashtun genocide that accelerated after 9/11. And yes, I said Pakistanis were killing Pakistanis and it must stop. But I referred principally to additional securitization as the cure, and immediately started giving military solutions to what is essentially a societal – if not national – problem.

What does that tell me about me? Well, I used to be much more idealistic than I am now. But it feels good to see that I used to believe in something so passionately: even if that level of devotion, allegiance and loyalty – apparently to just a part and not the whole – now seems to be misguided and injudicious, if not childishly imprudent and obviously unrequited. I have to admit that it required a heavy dose of desensitization before I began thinking more broadly – being rational, impartial and disengaged, but with academic curiosity – and constructively about terrorism, extremism, radicalization, and how to resolve them… Or rather, how to enable society to identify, address, and sustainably resolve them: if they see them as a problem to begin with! At the end of the day, there is only so much I can do, right?

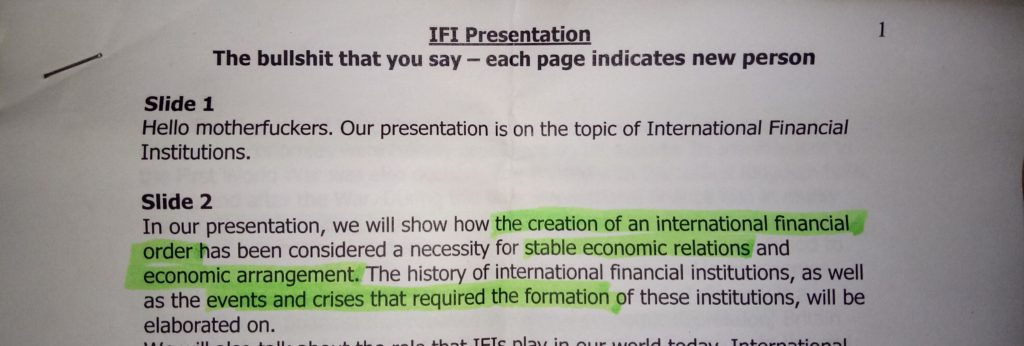

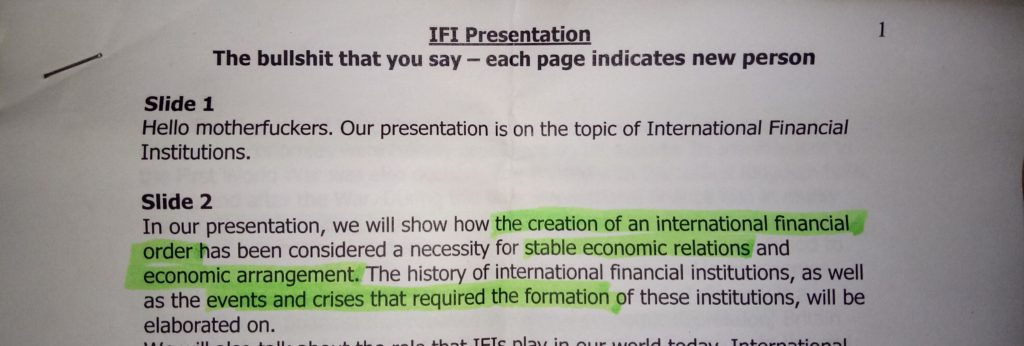

To be honest with everyone, I wasn’t really studying anything about military strategy or public security at LUMS. I majored in economics, and dabbled in some social sciences. It would be years before I would write reports on why negotiating with terrorists is the wrong approach, or how the quantum of terrorism across Pakistan shifted as the focus, capabilities and operational alliances of terrorist groups evolved. At LUMS, when I was not helping manage and operate student societies, I was writing essays and giving presentations on economic issues. Like this one group presentation on international financial institutions, or IFIs, where one of my group members prepared a script – basically outlining what to say on each slide, so we could understand the content and modify it accordingly – because I couldn’t attend group meetings since they overlapped with society meetings. Before you say I have no right to tell anyone about fixing their priorities, wait till you see how the script started:

And the script ended like this:

My apologies for the expletive language. Suffice it to say, neither me nor my group chose to read the script verbatim. We were good students – well, they were better while I was good enough – and none of us were stupid: all of us knew how to read. And thankfully, even I prepared in advance; but not without the shock at first glance and the fits of hilarity that ensued. Anyway, I’m just glad I got my honours degree on time, even though some would say I ‘barely’ graduated. And on the bright side, the ‘LUMS experience’ did prepare me for future success – as evident in my Masters scholarship and transcript scores – even if it turned me into a Thundercats villain. Go ahead, post a comment if you know what I’m talking about.

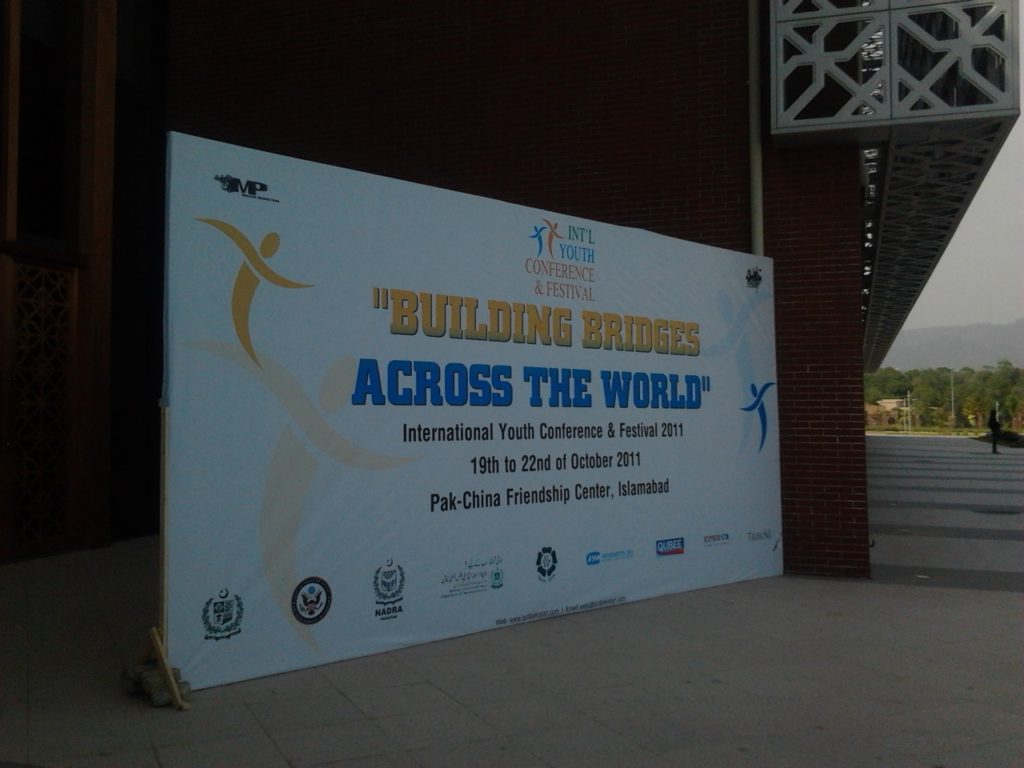

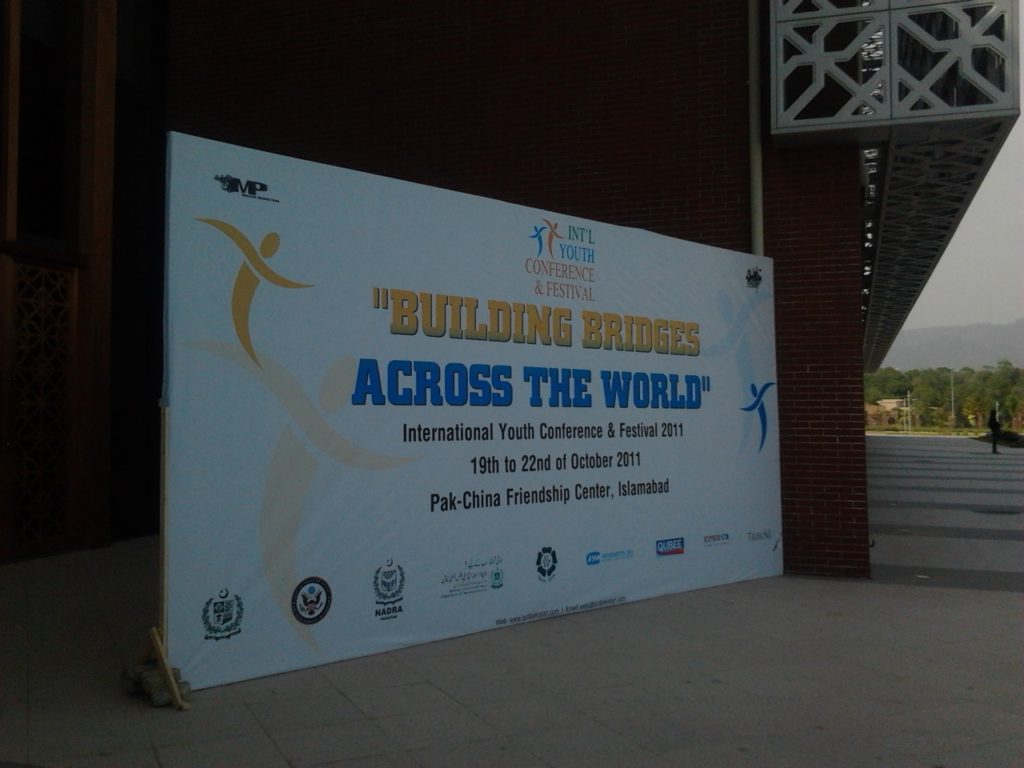

Another ‘mixed’ memory comes from 2011: evoking happy as well as sad feelings, and you will see why. This one is of helping to arrange the second International Youth Conference & Festival (IYCF 2011), with friends and other youth from across Pakistan, in attempts to galvanize Pakistan’s youth bulge, create cross-sectional and transformative social alliances, and preparing them – and ourselves – to deal with the nation’s problems.

In fact, here is Raza himself at IYCF 2011, speaking to Farhad Jarral and others:

Despite short respites like the one above, IYCF 2011 required hard work and honest intentions; in hindsight, maybe they paid off, or maybe they haven’t as yet. Maybe the youth of ten years ago have forgotten the message and adjusted to the everyday grind of life; maybe some of them are still struggling to do what’s right and make a difference. There is one person from IYCF 2011 who will always stand out for me: a young man from Quetta’s Hazara community, Irfan Ali, better known by the nom-de-plume Irfan Ali Khudi. At first, he appeared to be reserved and reticent, but that was hardly the case. A peace activist and rights defender from one of the deadliest parts of Pakistan, Irfan spoke only when he needed to, and chose his words very carefully, to the extent of stumbling over them just to make sure he got his ideas across. He was neither self-indulgent nor interested in wasting any time – and above all else, in spite of the demanding nature of his work and the odds that he faced, he had a charming smile that veiled contagious laughter.

This was the hardest thing to find, and even harder to look at.

Now what does this say about me? Maybe what I did then was right, but not enough. Maybe what I did then was wrong, or useless, possibly misguided, or even destructive. It was the senseless and brutal murder of Irfan Ali Khudi and many other Hazara Shia’s of Quetta – along with the untimely passing of thousands of Pakistanis killed by terrorists and extremist militants – which forced me to stop being a ‘keyboard warrior’ while human lives were becoming statistics, and actually do something about it; at least try to make a difference. Khudi’s watch has ended, he is in a much better place, but the fight he died fighting still continues: the struggle seems to have only gotten harder, not easier, more than eight years after his passing.

I would like say that I tried doing my part – in ways than I couldn’t even possibly recount or prove – along with many others, but even today I still feel like I haven’t done enough. And yet, along the way I found many others to be apathetic or nonchalant; unconcerned with doing their part in fixing the problems we faced then, which have metastasized into the monsters we see now. I could show you memories where you can clearly differentiate between the genuine concern of some and the blatant vanity of others, but my purpose isn’t to incite anyone – God knows it doesn’t take much to rile up a Pakistani, especially these days. Some of them could be part of the problem, but the essence of this struggle is to appeal to their reason and agitate their conscience, so that they could become part of the solution. It appears that, in the words of Robert Frost, I have promises to keep, and miles to go before I sleep.

Well, enough of the psychological waterboarding. How about some happy memories, some fond moments which could possibly extricate you from the gloom I have submerged you in?

So while Pakistan was in political turmoil during March 2009, as the lawyers’ movement continued to pressurize the-then PPP government to reinstate Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry, I was on an excursion with the LUMS Adventure Society to Gilgit Baltistan. Destination: Rattu – a small enclave surrounded by slopes, where people can come to ski. Since it was winter, the groups reaching Rattu had to drive from Astore and then trek for something like 12km to 20km. I for sure didn’t make it through the last stretch, and was carried into the camp before I froze in the snow. Sounds scary, or miserable? You tell me what it looks like:

No matter what happened, we – yes, myself included – trekked back through the snow from Rattu to Astore, and then caught our bus back to Lahore: spending our time on the road listening to Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan on repeat for hours on end. Even though protestors had embarked on their ‘Long March’ from Lahore en route to Islamabad via GT Road, at least we could brave the elements and didn’t have to call in a Pak Army chopper to evacuate or rescue us! It was a skiing tour, not a force reconnaissance mission in enemy territory. Or maybe LUMS Adventure trips nowadays are different from what they were back in my day…

Even though Rattu was serene and beautiful, and even though it was my first time seeing a snowy and utterly picturesque Pakistan, the apparently embarrassing entry to Rattu should’ve put me off all kinds of outdoor activities, right? Wrong.

Fast-forward to May 2015. Never one to say no to new things, I found out that in a country where I was still learning to speak the local language, myself and a few other foreigners – all Masters students – had been ‘shortlisted’ to take some Bachelors students on a trip to the Great Wall of China. Sounds pretty simple and straightforward, right? “Everyone visits the Great Wall when they’re in Beijing” is what you would say. Well, it wasn’t that kind of trip: and there was a reason older, more responsible and physically capable students were asked to guide younger, mostly Chinese students on a trek from Mutianyu village – some miles from the main Badaling tourist attraction where everyone goes to see the Great Wall – up the mountains to a secluded and partially decrepit section of the Wall. As if we were the Emperor’s soldiers getting ready to ambush the Mongols.

Yes, it was difficult; sometimes it got plain dangerous. And we weren’t responsible for just ourselves – we had to make sure the ‘kids’ got back to the university safe and sound. Pretty much like my best friend carrying me and my dislocated leg into the Rattu camp; though nothing as shocking as that happened during the Mutianyu trek.

I had fun on both excursions, and I thought it’d be worthwhile to take you all outside (virtually, of course) after being stuck in quarantine for a year or more.

In fact, just sit back down – I’m not done just yet.

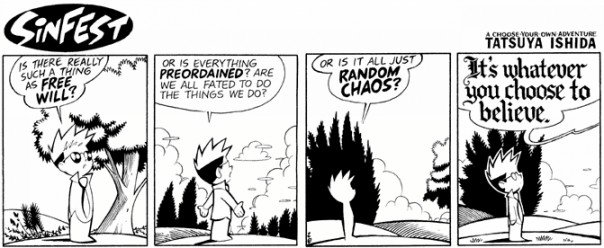

So what does all of this show? To me, it shows that memories are not positive or negative, happy or sad, in and of themselves: it’s whatever you make of them. Of course, memories are bound to invoke emotions, and that sentimentality is what we call nostalgia. But there are a huge differences between nostalgia, regret and procrastination. You can see yourself as a winner, and vow to continue acting, behaving or feeling that way; you can see opportunities to learn, and fix your inclinations and proclivities, your biases and harmful predispositions, to not repeat whatever mistakes you actually made or feel you made.

Okay, enough of you reading my words – here is something for you to do! Fair warning: it may be fun, or it may haunt you; depending on what it is, what it means to you, and whatever way you choose to look at it…

1. Find out what is the oldest picture you have saved with yourself, preferably on your online drive since it would go back further than your oh-so-brand-new laptop or cellphone, and also have them all arranged in chronological order.

Apps like Google Photos and iTunes Backup even have an inbuilt ‘flashback’ feature, giving you the opportunity to see what pictures you saved or uploaded exactly one, two, three or more years from the day.

Have you found your oldest picture that you have saved yet? Good, now wait right there!

2. Instead of starting to scroll slowly to the present, pick a month and a year, and scroll to that timeframe. Now scroll to a random picture taken or saved during that month and year, or just start from the beginning or the end of that month. Do you find happy memories, or just sad memories? Do you have any funny or memorable videos saved? How do you feel after going through your ‘saved’ memories from that time in your life – and is there any picture or video that you wish you’d made, or saved, but haven’t?

If you start to feel happy, hold on to that feeling. Don’t just remember it: memorialize it. You may not be in it anymore, but it will always be yours and you can always relive it whenever you want, or whenever you choose to. If you need to jolt yourself back to reality, just pick the same date – the same day and month – for the year 2020, and see whether you still had something to be happy about, or whether it was just a crappy year all round!

And if you start to feel sad or depressed, just ask yourself: why do I feel this way? Is it this memory that invokes the negativity in me, or is it the regret I have of not doing something different? Try to dissociate your emotion from the memory, if possible at all, and try to see what you can learn from this ongoing experience: the experience of being nostalgic, but suddenly arriving at a memory – a reliving of your past – that you probably wish you had forgotten. Can you change for the better, and have you? Did you make any mistakes, and do you keep making them or have you learnt your lesson? Conversely, has the trauma of that negative memory turned you into exactly the opposite of what you were? Is that a good thing or a bad thing?

Is the sadness too much for you? Well, then here’s what you do:

3. Go to your most recent picture, and then pick another month and year – ideally furthest away from what you picked before. For instance, if picking September in 2014 made you depressed, pick something between February and June (both inclusive), and go either five years back or five years ahead from 2014. You can choose the same date, or a different date, because the point is not to make you feel happy or sad – it is to allow you to see for yourself what power nostalgia has, what it does to you, and what it can do for you.

Remember: it’s what you choose to make of it. It always is.

Maybe that’s all it is…

Postscript: If you liked this article, please show some love and share your comments. If you didn’t like this article, please throw something sharp and heavy at Raza, ideally when he’s not looking. If he complains, tell him it was Shemrez’s book on Nostalgia, and that you were just trying to ‘facebook’ him.

My friend, mentor, and not-too-distant relative Raza Rumi recently shared an article on nostalgia, authored by Jamie Bell for Big Think. The article, titled "Nostalgia triggers a reward pathway in our brains, according to science", is a succinct yet insightful read: it not only defines nostalgia and explains the historical evolution of the connotations attached to it, but also reviews neurological and psychological studies done on the impact nostalgia has on human beings. I have hyperlinked the article because you should definitely go and read it yourself – though I will still try to list the salient features (or that which I derived) from it hereunder:

- Nostalgia is generally defined as " sentimentality for the past" and each individual has their own subjective notion(s) and emotion(s) associated with both sentimentality and, in turn, with nostalgia;

- Despite our discrete and subjective experiences of nostalgia, there is a positive complementarity between memory and reward systems in our brain which is specifically triggered whenever anyone experiences nostalgia;

- Though originally thought of as a disease, nostalgia can now be considered "a vehicle for travelling beyond the suffocating confines of space and time";

- Scientists believe that nostalgia has a critical role to play in psychological resilience: it can be used to counteract loneliness and magnify perceptions of social support; it is positively correlated to perseverance and the ability to recover from traumas; and it also nurtures creativity and encourages neophilia (which is an openness to experience novelties, distinct from philoneism which is an excessive love for new things).

My response to the article is simple: purely from my own personal experiences, nostalgia is indeed a powerful memory tool within our brain, and it also has many potential recuperative qualities. While I was asked to write an essay on it, I could definitely write a book about it – I'm sure by the end of this article, you might be able to see why.

In my opinion, there is definitely a lot of truth to what the article says about nostalgia – going beyond my individual experience, I would say that results of credible academic research by experts cannot and should not be refuted offhand. But, again, you should definitely read the article for yourself – and I would invite psychiatrists, psychologists, neurologists, and even philosophers, to comment on the nature of nostalgia and its impact on human beings and human life in general.

Tell me something I don't know

While we wait for the experts and intellectuals to further enlighten us on nostalgia, longing and wistfulness, let me share my own experiential perceptions with you. I used to be an information collector and hoarder – maybe I still am – but my understanding and constant practice of research techniques and methodologies, as well as forays into data analytics, allowed me to hone and polish myself professionally into an ‘intelligence analyst’: though that never really worked in my favour. Though I can obviously neither confirm nor deny anything, imputations that I belong or belonged to a mysterious world of ‘cloak and dagger’ is amusing at best, and excruciating at worst. So please allow me to digress.

Acquiring information, possessing knowledge, and fostering an understanding of concepts, issues and disciplines is really only the first step: one can only develop a meaningful comprehension, or obtain verifiable results, after gaining an insight into what information is useful and what isn’t, which knowledge is verifiably true and which is merely opinion or hearsay, and whether concepts can actually withstand robust testing in their theoretical validity as well as practical cogency – whether they intuitively ‘make sense’ and have any application in or relevance to real life, or not. According to prominent motivational speaker Dr. Joe Dispenza, “a memory without the emotional charge is called wisdom”; but as we all know, memories can’t be so easily dissociated from emotion. Not without the commensurate self-reflection and an inordinate – but not infinite – amount of cognitive discipline. Wisdom is the daughter of experience, with memory and emotion being two additional variables that each of us must contend with: not to overcome or master, but to find a balance within that gives us contentment.

Nostalgia isn’t as scientific or as controllable as the above processes. It occurs as a natural human instinct if not a reaction to environment, circumstances and / or emotions. In my opinion, nostalgia is more of an impulse than a reflex: reliving the past is easy, because you’ve already lived it once, and nostalgia allows you to do that again. There is nothing wrong with being sentimental about one’s own past, about one’s own perspectives and emotions regarding what is a lived experience, and therefore subjective in essence. Where that sentimentality becomes negative, even harmful, is when it is clouded by "what if" and "I should’ve" – nostalgia should invoke greater understanding if not unblemished happiness; it should not create lakes of regret for one to wallow in. One should fondly remember happy memories and the good times, and derive a greater understanding of one’s own self from the sad memories and tribulations. To avoid nostalgia becoming procrastination, there are two simple tools to use: always remember that sometimes you win, while at other times you learn; and it is infinitely wiser to plan for the future, even in tiny incremental steps, rather than just dreaming about a happier time that you ‘deserve’ or ‘hope to live’ in the future. But I will be the first to acknowledge that all that is easier said than done.

So my point is: nostalgia should be a positive sensation. If it only fills you with depression, remorse and regret, that is too much negative sentimentality that either invokes immense trauma, and is something that you are unable – or maybe psychosocially unwilling – to come to terms with. The emotive burden of regret will not let you learn anything. And if nostalgia of the past makes you dream incessantly about the future, if it makes you wish to recreate or prolong a good memory in a way that keeps you excessively stationary and leads you to excessively procrastinate, then you haven’t learned anything and you need to physically do something to make your dreams a reality. Make a list; compartmentalize your long-term goals into medium- and short-term steps; give yourself targets that are rational and achievable on a daily basis; make sure you are flexible and can adjust to the changes in circumstance and environment; always have alternates for your main plan; start small so that you have something big at the end; and most importantly, hope for the best, but always be prepared for the worst. Otherwise procrastination – which is essentially conjuring up dreams that have significant meaning but are not followed through with action – will destroy you.

Me and My Nostalgia

How does nostalgia work for me? I would describe myself as imaginative instead of intelligent, as descriptive instead of verbose, and a researcher of reality forever teased by magic realism. The reason I told Raza I could write a book on the power of nostalgia, based on my own personal experiences – of life, memories, and reminiscence of longing as well as melancholy – is because I (sometimes literally) keep most if not all the receipts. Take it whichever way it suits you: maybe I’ve been brought up to always have to prove myself, or maybe I’ve always had to prove to myself that all of it was real and not just a vivid hallucination or a figment of my imagination. But I’m sure everyone can agree that the proof can speak for itself; beyond me presenting it, I acknowledge that everyone can have their own individual interpretation thereof, because everyone has a right to have their own opinion – call it what you want to. Acknowledgment does not necessarily have to be concession.

Intelligence will never stop being beautiful, but it takes something more than intelligence to act intelligently…

Now let me take you along on a ride through memories good and bad, times that made me happy and sad; since this is supposed to be about me and my nostalgia, I acknowledge the indispensable roles that others have performed in the episodes of my past which have fashioned and generated these memories, without necessarily lacerating old wounds for myself or anyone else. Yes, that means no love notes scribbled in books on politics and leadership.

While I reserve copyrights of the following for myself, I would be remiss to not give credit where it’s due: thank you to everyone who features in the memories I am about to present – I think they call it a ‘shout-out’ these days.

Auditory Nostalgia

For the past fifteen years or so, I have been studying terrorism and extremism in addition to my research and work on political economy and factors affecting social mobilization (especially youth mobilization) in Pakistan. Sometimes it is hard for me to believe that I am in fact that old, but hey, Aaliyah Haughton said “age ain’t nothing but a number”, right? May she forever rest in peace.

Which reminds me: Jamie Bell also states in her article that music can trigger nostalgia. In that sense, I’d like to think I have a veritable jukebox inside my head. But one of my favourite lyrics – a phrase you might find across my social media – is from Queens of the Stone Age: “I want something good to die for, to make it beautiful to live”…

I don’t really have a morbid fascination with death and dying; but I definitely have an enduring – dare I say ‘undying’ – interest in preventing death and destruction.

It’s only words, only words after all…

Textual Nostalgia

How do I know it’s been nearly fifteen years? Well, there used to be a publication at LUMS called ‘The Political Animal’. Published by the Law & Politics Society, or LPS, it contained contributions from students as well as professors on important political issues of the time. In 2008, I wrote an alarmist article titled “We are at war!”. I’ve been trying to find that issue – especially since it had a spoof Facebook profile of the-then Law Minister, Wasi Zafar, as a full page item on the back cover – but with no success as yet. Why did I write that? Maybe because I was an Assistant Editor of said magazine and just had to contribute something, or maybe I felt obliged to put in a pro-military but pessimistic viewpoint on the security situation of the country as it was at the time. Did it help? Maybe. Did it make me a good journalist? No. Did I learn my lesson? Of course not!

A year later, I wrote another article titled “The Way Out”. This time, the security situation was worse than before, and the military itself appeared ill-placed at best, or incapable at worst, to deal with its core mandate: national security. So I set about trying to rile up the people of Pakistan – the general citizenry, the common man, anyone who still had the ethos of ‘hum hain Pakistani, hum toh jeetenge, haan jeetenge’ – to come to their senses, come to grips with how extremist militants had begun using Islam to terrorize Muslims and other Pakistanis, and at least come together to agree on some basic principles if not figure out a way to comprehensively deal with the twin menace of extremism and terrorism.

Yes, I said the true danger lies in the radicalization of the Pakistani youth. Yes, I said our ‘strategic assets’ had come back to haunt us. Yes, I called out the Pashtun genocide that accelerated after 9/11. And yes, I said Pakistanis were killing Pakistanis and it must stop. But I referred principally to additional securitization as the cure, and immediately started giving military solutions to what is essentially a societal – if not national – problem.

What does that tell me about me? Well, I used to be much more idealistic than I am now. But it feels good to see that I used to believe in something so passionately: even if that level of devotion, allegiance and loyalty – apparently to just a part and not the whole – now seems to be misguided and injudicious, if not childishly imprudent and obviously unrequited. I have to admit that it required a heavy dose of desensitization before I began thinking more broadly – being rational, impartial and disengaged, but with academic curiosity – and constructively about terrorism, extremism, radicalization, and how to resolve them… Or rather, how to enable society to identify, address, and sustainably resolve them: if they see them as a problem to begin with! At the end of the day, there is only so much I can do, right?

To be honest with everyone, I wasn’t really studying anything about military strategy or public security at LUMS. I majored in economics, and dabbled in some social sciences. It would be years before I would write reports on why negotiating with terrorists is the wrong approach, or how the quantum of terrorism across Pakistan shifted as the focus, capabilities and operational alliances of terrorist groups evolved. At LUMS, when I was not helping manage and operate student societies, I was writing essays and giving presentations on economic issues. Like this one group presentation on international financial institutions, or IFIs, where one of my group members prepared a script – basically outlining what to say on each slide, so we could understand the content and modify it accordingly – because I couldn’t attend group meetings since they overlapped with society meetings. Before you say I have no right to tell anyone about fixing their priorities, wait till you see how the script started:

And the script ended like this:

My apologies for the expletive language. Suffice it to say, neither me nor my group chose to read the script verbatim. We were good students – well, they were better while I was good enough – and none of us were stupid: all of us knew how to read. And thankfully, even I prepared in advance; but not without the shock at first glance and the fits of hilarity that ensued. Anyway, I’m just glad I got my honours degree on time, even though some would say I ‘barely’ graduated. And on the bright side, the ‘LUMS experience’ did prepare me for future success – as evident in my Masters scholarship and transcript scores – even if it turned me into a Thundercats villain. Go ahead, post a comment if you know what I’m talking about.

Video Nostalgia – An electronic memory...

Another ‘mixed’ memory comes from 2011: evoking happy as well as sad feelings, and you will see why. This one is of helping to arrange the second International Youth Conference & Festival (IYCF 2011), with friends and other youth from across Pakistan, in attempts to galvanize Pakistan’s youth bulge, create cross-sectional and transformative social alliances, and preparing them – and ourselves – to deal with the nation’s problems.

In fact, here is Raza himself at IYCF 2011, speaking to Farhad Jarral and others:

Despite short respites like the one above, IYCF 2011 required hard work and honest intentions; in hindsight, maybe they paid off, or maybe they haven’t as yet. Maybe the youth of ten years ago have forgotten the message and adjusted to the everyday grind of life; maybe some of them are still struggling to do what’s right and make a difference. There is one person from IYCF 2011 who will always stand out for me: a young man from Quetta’s Hazara community, Irfan Ali, better known by the nom-de-plume Irfan Ali Khudi. At first, he appeared to be reserved and reticent, but that was hardly the case. A peace activist and rights defender from one of the deadliest parts of Pakistan, Irfan spoke only when he needed to, and chose his words very carefully, to the extent of stumbling over them just to make sure he got his ideas across. He was neither self-indulgent nor interested in wasting any time – and above all else, in spite of the demanding nature of his work and the odds that he faced, he had a charming smile that veiled contagious laughter.

This was the hardest thing to find, and even harder to look at.

Now what does this say about me? Maybe what I did then was right, but not enough. Maybe what I did then was wrong, or useless, possibly misguided, or even destructive. It was the senseless and brutal murder of Irfan Ali Khudi and many other Hazara Shia’s of Quetta – along with the untimely passing of thousands of Pakistanis killed by terrorists and extremist militants – which forced me to stop being a ‘keyboard warrior’ while human lives were becoming statistics, and actually do something about it; at least try to make a difference. Khudi’s watch has ended, he is in a much better place, but the fight he died fighting still continues: the struggle seems to have only gotten harder, not easier, more than eight years after his passing.

I would like say that I tried doing my part – in ways than I couldn’t even possibly recount or prove – along with many others, but even today I still feel like I haven’t done enough. And yet, along the way I found many others to be apathetic or nonchalant; unconcerned with doing their part in fixing the problems we faced then, which have metastasized into the monsters we see now. I could show you memories where you can clearly differentiate between the genuine concern of some and the blatant vanity of others, but my purpose isn’t to incite anyone – God knows it doesn’t take much to rile up a Pakistani, especially these days. Some of them could be part of the problem, but the essence of this struggle is to appeal to their reason and agitate their conscience, so that they could become part of the solution. It appears that, in the words of Robert Frost, I have promises to keep, and miles to go before I sleep.

Well, enough of the psychological waterboarding. How about some happy memories, some fond moments which could possibly extricate you from the gloom I have submerged you in?

Visual Nostalgia – A Picture is worth…

So while Pakistan was in political turmoil during March 2009, as the lawyers’ movement continued to pressurize the-then PPP government to reinstate Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry, I was on an excursion with the LUMS Adventure Society to Gilgit Baltistan. Destination: Rattu – a small enclave surrounded by slopes, where people can come to ski. Since it was winter, the groups reaching Rattu had to drive from Astore and then trek for something like 12km to 20km. I for sure didn’t make it through the last stretch, and was carried into the camp before I froze in the snow. Sounds scary, or miserable? You tell me what it looks like:

No matter what happened, we – yes, myself included – trekked back through the snow from Rattu to Astore, and then caught our bus back to Lahore: spending our time on the road listening to Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan on repeat for hours on end. Even though protestors had embarked on their ‘Long March’ from Lahore en route to Islamabad via GT Road, at least we could brave the elements and didn’t have to call in a Pak Army chopper to evacuate or rescue us! It was a skiing tour, not a force reconnaissance mission in enemy territory. Or maybe LUMS Adventure trips nowadays are different from what they were back in my day…

Even though Rattu was serene and beautiful, and even though it was my first time seeing a snowy and utterly picturesque Pakistan, the apparently embarrassing entry to Rattu should’ve put me off all kinds of outdoor activities, right? Wrong.

Fast-forward to May 2015. Never one to say no to new things, I found out that in a country where I was still learning to speak the local language, myself and a few other foreigners – all Masters students – had been ‘shortlisted’ to take some Bachelors students on a trip to the Great Wall of China. Sounds pretty simple and straightforward, right? “Everyone visits the Great Wall when they’re in Beijing” is what you would say. Well, it wasn’t that kind of trip: and there was a reason older, more responsible and physically capable students were asked to guide younger, mostly Chinese students on a trek from Mutianyu village – some miles from the main Badaling tourist attraction where everyone goes to see the Great Wall – up the mountains to a secluded and partially decrepit section of the Wall. As if we were the Emperor’s soldiers getting ready to ambush the Mongols.

Yes, it was difficult; sometimes it got plain dangerous. And we weren’t responsible for just ourselves – we had to make sure the ‘kids’ got back to the university safe and sound. Pretty much like my best friend carrying me and my dislocated leg into the Rattu camp; though nothing as shocking as that happened during the Mutianyu trek.

I had fun on both excursions, and I thought it’d be worthwhile to take you all outside (virtually, of course) after being stuck in quarantine for a year or more.

But remember: if you suddenly feel inspired to go outside and challenge nature yourself right now, PLEASE wear a mask PROPERLY, always keep a sanitizer on you and use it regularly, and maintain social distance as often as you can.

In fact, just sit back down – I’m not done just yet.

So what does all of this show? To me, it shows that memories are not positive or negative, happy or sad, in and of themselves: it’s whatever you make of them. Of course, memories are bound to invoke emotions, and that sentimentality is what we call nostalgia. But there are a huge differences between nostalgia, regret and procrastination. You can see yourself as a winner, and vow to continue acting, behaving or feeling that way; you can see opportunities to learn, and fix your inclinations and proclivities, your biases and harmful predispositions, to not repeat whatever mistakes you actually made or feel you made.

Now it’s YOUR turn!

Okay, enough of you reading my words – here is something for you to do! Fair warning: it may be fun, or it may haunt you; depending on what it is, what it means to you, and whatever way you choose to look at it…

1. Find out what is the oldest picture you have saved with yourself, preferably on your online drive since it would go back further than your oh-so-brand-new laptop or cellphone, and also have them all arranged in chronological order.

Apps like Google Photos and iTunes Backup even have an inbuilt ‘flashback’ feature, giving you the opportunity to see what pictures you saved or uploaded exactly one, two, three or more years from the day.

Have you found your oldest picture that you have saved yet? Good, now wait right there!

2. Instead of starting to scroll slowly to the present, pick a month and a year, and scroll to that timeframe. Now scroll to a random picture taken or saved during that month and year, or just start from the beginning or the end of that month. Do you find happy memories, or just sad memories? Do you have any funny or memorable videos saved? How do you feel after going through your ‘saved’ memories from that time in your life – and is there any picture or video that you wish you’d made, or saved, but haven’t?

If you start to feel happy, hold on to that feeling. Don’t just remember it: memorialize it. You may not be in it anymore, but it will always be yours and you can always relive it whenever you want, or whenever you choose to. If you need to jolt yourself back to reality, just pick the same date – the same day and month – for the year 2020, and see whether you still had something to be happy about, or whether it was just a crappy year all round!

And if you start to feel sad or depressed, just ask yourself: why do I feel this way? Is it this memory that invokes the negativity in me, or is it the regret I have of not doing something different? Try to dissociate your emotion from the memory, if possible at all, and try to see what you can learn from this ongoing experience: the experience of being nostalgic, but suddenly arriving at a memory – a reliving of your past – that you probably wish you had forgotten. Can you change for the better, and have you? Did you make any mistakes, and do you keep making them or have you learnt your lesson? Conversely, has the trauma of that negative memory turned you into exactly the opposite of what you were? Is that a good thing or a bad thing?

Is the sadness too much for you? Well, then here’s what you do:

3. Go to your most recent picture, and then pick another month and year – ideally furthest away from what you picked before. For instance, if picking September in 2014 made you depressed, pick something between February and June (both inclusive), and go either five years back or five years ahead from 2014. You can choose the same date, or a different date, because the point is not to make you feel happy or sad – it is to allow you to see for yourself what power nostalgia has, what it does to you, and what it can do for you.

Remember: it’s what you choose to make of it. It always is.

Maybe that’s all it is…

Postscript: If you liked this article, please show some love and share your comments. If you didn’t like this article, please throw something sharp and heavy at Raza, ideally when he’s not looking. If he complains, tell him it was Shemrez’s book on Nostalgia, and that you were just trying to ‘facebook’ him.