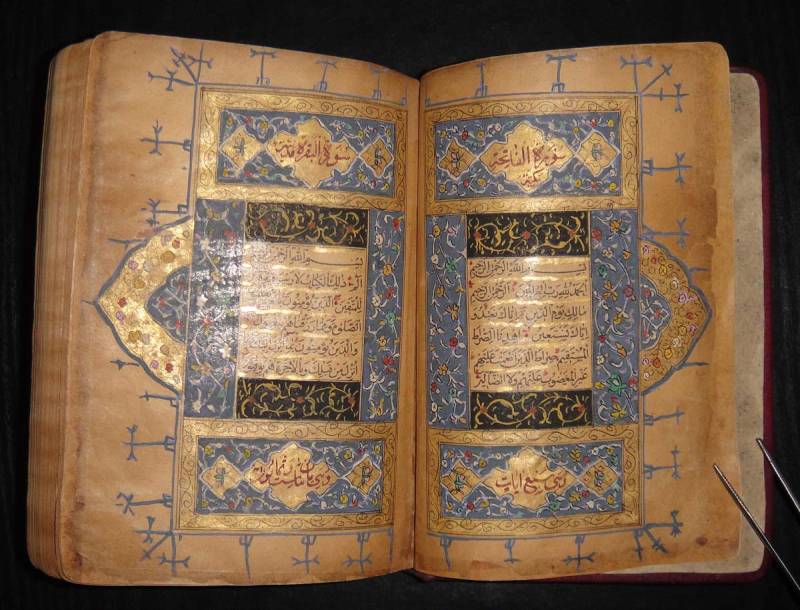

Muslims believe in the absolute reality of the Quran as the final word of God revealed through Prophet Muhammad (pbuh). God took personal responsibly of its safety and has made sure that no word, comma or fullstop can ever change. It was made possible initially by the Prophet when he instructed that the Quran be memorised, recorded, and compiled under his direct supervision. As a tradition, the Quran has since been consistently read, learned by heart, and copied by millions of Muslims around the world to ensure its integrity and safekeeping.

Islam had initiated as a local threat to false beliefs and traditions but rapidly grew to challenge the regional and global religio-political establishment. Therefore, Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) and his message (Quran) have always been the focus of unrelenting criticism, conspiracies, and attacks from day one. Considering the nature of these multi-pronged (intellectual, religious, political, military) assaults, it is understandable that they could not have been carried out without coordinated efforts by enemies and collaborators, with a little help from our naïve friends. Since, Quran could not be adulterated due to the inherent historical safeguards, an evil conspiracy of Naskh of Quranic verses was introduced.

Naskh, meaning abrogation, is a concept, which proposed that a Quranic verse could be (God forbid) superseded, cancelled or revoked by a later verse. The function of a verse being abrogated is called (Al-Naskh), and the abrogated verse is called (Al-Mansukh). This concept was invented several decades after Prophet Muhammad’s (pbuh) departure, and cemented by some Muslim academics including Ahmed bin Ishaq al-Dinary (d. 318 AH), Muhammad Bin Bahr al-Asbahany (d. 322 AH), Hebat Allah Bin Salamah (d. 410 AH), and Muhammad Bin Musa al-Hazmy (d. 548 AH). It had become an established principle in Sharia by the 9th century, and orthodox scholars have since found the theory so crucial to Islamic belief that they takfir (declare non-believer) those who oppose it. It has since been widely exploited by non-Muslims to cast aspersions on the divinity of the Quran.

Muslim and non-Muslim scholars agree that not even a single verse in the Quran unequivocally points to the abrogation of another verse. Similarly, no reliable Hadith mentions that any verse of the Quran was being abrogated. As long as the companions of the Prophet (pbuh) were alive, no evidence for the abrogation of Quranic verses was found in the early history of Islam. However, all traditional schools of thought in Islam believe in the abrogation of Quranic verses to this day.

According to their Imams and the present-day leaders, up to 248 verses have been abrogated; these are in addition to those 363 abrogated verses, according to them, that were not recorded (God forbid) when the Quran was compiled (according to them) during the reign of Hazrat Usman. As expected, these schools of thought do not agree on the number, reasons or chronology of these abrogated verses.

Three essential forms of Naskh mentioned in the Islamic literature are: abrogation of a ruling (hukm) but not the text; abrogation of the wording but not of the ruling; abrogation of both the verse and the ruling. The relevant verses need to meet the criteria of “divinity”, “conflict”, “chronology”, “historical evidence”, and “scholarly consensus”. The examples of the rulings based on abrogation include, a ban on alcohol, a change in the direction of qibla, divorced women, inheritance, fasting, night prayer, etc. Needless to say, all schools of thought disagree among themselves about the scope, choice, and definition of the abrogation. Most of them unfortunately agree, explicitly or implicitly, that Ahadith can somehow overrule the Quran.

The justifications given in the Islamic literature for the concept of Naskh are rather interesting. Some argued that it reflected how the needs of the Muslim community had changed over the course of Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) campaign. Others proposed that it portrayed Allah’s wisdom in dealing with different situations, and offered a special flexibility to Muslims. It was also pointed out that since Islam had abrogated some laws espoused by other erstwhile religions; it was only fair that it adopted a consistent approach. And finally, it was stressed that only God knows the temporariness or permanence of any entity (a ruling in this case); when the expiration point is reached, God made it known that He intended it as temporary all along.

The concept of abrogation of Quranic verses was actually invented to justify the false and contradictory material contained in the volumes and volumes of Ahadith which had come into being since Prophet Muhammad’s departure. Naskh is not an article of faith of Islam, like belief in the prophets, angels, and books of Allah. It was originally a part of the pyramid of methods that were employed by ancient scholars of Islamic jurisprudence who worked with Ahadith. They would first try and “harmonize” a hadith with another; but If that failed, they would look for signs of abrogation that one saying/doing by the Prophet Muhammad was earlier than the other and had been replaced by the later saying/doing. This remained the case until some wicked minds decided to extend the same practice to the Quran first, and then took the liberty of mixing up Ahadith and the Quran within the same method.

Even as an academic technique, Naskh has attracted a great deal of criticism because it posed a difficult doctrinal conundrum. It suggested that God changed his mind frequently, and that He realized something later, which He was unaware of when revealing the original verse. It brought God down to the human level where we reflect on our past decisions, and change course after learning from our mistakes. Some tried to open this door though verses of the Quran by exploiting their wrong translations or interpretations. For example, Imam Razi (1150-1210 CE) who believed in Naskh later admitted that he had wrongly believed that the verses (Quran 5:104-108) advocated it. Shaikh Muhammad Abduh (1849-1905 CE) and Sir Syed Ahmed Khan (1817-1898 CE) also smashed the claims of those who tried to seek support from these and other verses though the trap of their Shan-e-Nazool (background narrative).

Abu Muslim al-Isphahani (254-322 CE) was the first known scholar to have rejected the concept of Naskh out rightly. Similar to the Mu’tazilah works, his masterpiece, Jami ‘al-Ta’wil, on the subject of Naskh has been conveniently lost to the history. He felt that the concept was an insult to the integrity and value of the revelation of God. People like Imam Shawkani (1759-1839 CE) abused him to no end for taking this stance. However, we know from Imam Razi how they had argued that it would be ludicrous to assume that a ruling regarding Naskh can exist without an explicit verse and vice versa; and that the whole concept was redundant because it professed God as ignorant. Furthermore, Naskh depends fundamentally on the chronology of verses, and there was no way of determining this with absolute certainty. Shaikh Abduh also argued why Naskh was employed during the 23 years of the Quran's revelation, but could not be commissioned over the next fourteen hundred years when greater social and life changes appeared.

Imam Shafi (767-820 CE) is reported to have got so upset by the concept of Ahadith overruling the Quran though Naskh that he declared it Murdood and akin to creating anarchy. Imam Hanbal (780-855 CE), who believed in Ahadith interpreting the Quran, felt the same way and said that he could never even think about it. Al-Qartabi (1214-1273 CE) has also referred to great Imams of the Malaki School to confirm that they held the same position. An Ijma (consensus) of scholars cannot endorse Naskh either because it has no precedence in the Quran, Hadith, Sunnah or the history of Islam. Ibne Hazam (994-1064 CE) was initially in its favour, but soon after retracted his opinion. Similarly, if we start using the instrument of Islamic logic to abrogate Quranic verses, it could turn into an endless farce. The Sufi jurist al-Sharani (1492-1565 CE) considered claims of abrogation to be the choice of narrow-minded jurists whose hearts God had not illuminated with his Light.

The rationalist scholars have always rejected Naskh as poor scholarship and on the grounds that the word of God cannot contain have contradictions. The focused denunciation, however, started in the 19th century when reformist like Shaikh Abduh, Sir Syed, and Rashid Rida (1865-1935 CE) highlighted it as invalid. Sir Syed received extreme hostility due to it and was called Kafir and Naturee among others things. Rationalist views about Naskh were maintained in the 20th century by prominent Islamic scholars including Muhammad Amin (Egypt), Aslam Jairajpuri, Allama Iqbal and his protégé Allama Parwez. The latter wrote “Tubweebul Quran” and “Qurani Faisalay”, which should have killed the whole issue academically. However, the most remarkable work on this topic is Tafseer Mansukh ul Quran (1974) by Rahmat Ullah Tariq. In his research spanned over 20 years, he has not only covered all the angles, but also discussed each ‘Mansukh’ verse and destroyed the proponents’ arguments by utilising their own references.

Islam had initiated as a local threat to false beliefs and traditions but rapidly grew to challenge the regional and global religio-political establishment. Therefore, Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) and his message (Quran) have always been the focus of unrelenting criticism, conspiracies, and attacks from day one. Considering the nature of these multi-pronged (intellectual, religious, political, military) assaults, it is understandable that they could not have been carried out without coordinated efforts by enemies and collaborators, with a little help from our naïve friends. Since, Quran could not be adulterated due to the inherent historical safeguards, an evil conspiracy of Naskh of Quranic verses was introduced.

Naskh, meaning abrogation, is a concept, which proposed that a Quranic verse could be (God forbid) superseded, cancelled or revoked by a later verse. The function of a verse being abrogated is called (Al-Naskh), and the abrogated verse is called (Al-Mansukh). This concept was invented several decades after Prophet Muhammad’s (pbuh) departure, and cemented by some Muslim academics including Ahmed bin Ishaq al-Dinary (d. 318 AH), Muhammad Bin Bahr al-Asbahany (d. 322 AH), Hebat Allah Bin Salamah (d. 410 AH), and Muhammad Bin Musa al-Hazmy (d. 548 AH). It had become an established principle in Sharia by the 9th century, and orthodox scholars have since found the theory so crucial to Islamic belief that they takfir (declare non-believer) those who oppose it. It has since been widely exploited by non-Muslims to cast aspersions on the divinity of the Quran.

Muslim and non-Muslim scholars agree that not even a single verse in the Quran unequivocally points to the abrogation of another verse. Similarly, no reliable Hadith mentions that any verse of the Quran was being abrogated. As long as the companions of the Prophet (pbuh) were alive, no evidence for the abrogation of Quranic verses was found in the early history of Islam. However, all traditional schools of thought in Islam believe in the abrogation of Quranic verses to this day.

According to their Imams and the present-day leaders, up to 248 verses have been abrogated; these are in addition to those 363 abrogated verses, according to them, that were not recorded (God forbid) when the Quran was compiled (according to them) during the reign of Hazrat Usman. As expected, these schools of thought do not agree on the number, reasons or chronology of these abrogated verses.

Three essential forms of Naskh mentioned in the Islamic literature are: abrogation of a ruling (hukm) but not the text; abrogation of the wording but not of the ruling; abrogation of both the verse and the ruling. The relevant verses need to meet the criteria of “divinity”, “conflict”, “chronology”, “historical evidence”, and “scholarly consensus”. The examples of the rulings based on abrogation include, a ban on alcohol, a change in the direction of qibla, divorced women, inheritance, fasting, night prayer, etc. Needless to say, all schools of thought disagree among themselves about the scope, choice, and definition of the abrogation. Most of them unfortunately agree, explicitly or implicitly, that Ahadith can somehow overrule the Quran.

The justifications given in the Islamic literature for the concept of Naskh are rather interesting. Some argued that it reflected how the needs of the Muslim community had changed over the course of Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) campaign. Others proposed that it portrayed Allah’s wisdom in dealing with different situations, and offered a special flexibility to Muslims. It was also pointed out that since Islam had abrogated some laws espoused by other erstwhile religions; it was only fair that it adopted a consistent approach. And finally, it was stressed that only God knows the temporariness or permanence of any entity (a ruling in this case); when the expiration point is reached, God made it known that He intended it as temporary all along.

The concept of abrogation of Quranic verses was actually invented to justify the false and contradictory material contained in the volumes and volumes of Ahadith which had come into being since Prophet Muhammad’s departure. Naskh is not an article of faith of Islam, like belief in the prophets, angels, and books of Allah. It was originally a part of the pyramid of methods that were employed by ancient scholars of Islamic jurisprudence who worked with Ahadith. They would first try and “harmonize” a hadith with another; but If that failed, they would look for signs of abrogation that one saying/doing by the Prophet Muhammad was earlier than the other and had been replaced by the later saying/doing. This remained the case until some wicked minds decided to extend the same practice to the Quran first, and then took the liberty of mixing up Ahadith and the Quran within the same method.

Even as an academic technique, Naskh has attracted a great deal of criticism because it posed a difficult doctrinal conundrum. It suggested that God changed his mind frequently, and that He realized something later, which He was unaware of when revealing the original verse. It brought God down to the human level where we reflect on our past decisions, and change course after learning from our mistakes. Some tried to open this door though verses of the Quran by exploiting their wrong translations or interpretations. For example, Imam Razi (1150-1210 CE) who believed in Naskh later admitted that he had wrongly believed that the verses (Quran 5:104-108) advocated it. Shaikh Muhammad Abduh (1849-1905 CE) and Sir Syed Ahmed Khan (1817-1898 CE) also smashed the claims of those who tried to seek support from these and other verses though the trap of their Shan-e-Nazool (background narrative).

Abu Muslim al-Isphahani (254-322 CE) was the first known scholar to have rejected the concept of Naskh out rightly. Similar to the Mu’tazilah works, his masterpiece, Jami ‘al-Ta’wil, on the subject of Naskh has been conveniently lost to the history. He felt that the concept was an insult to the integrity and value of the revelation of God. People like Imam Shawkani (1759-1839 CE) abused him to no end for taking this stance. However, we know from Imam Razi how they had argued that it would be ludicrous to assume that a ruling regarding Naskh can exist without an explicit verse and vice versa; and that the whole concept was redundant because it professed God as ignorant. Furthermore, Naskh depends fundamentally on the chronology of verses, and there was no way of determining this with absolute certainty. Shaikh Abduh also argued why Naskh was employed during the 23 years of the Quran's revelation, but could not be commissioned over the next fourteen hundred years when greater social and life changes appeared.

Imam Shafi (767-820 CE) is reported to have got so upset by the concept of Ahadith overruling the Quran though Naskh that he declared it Murdood and akin to creating anarchy. Imam Hanbal (780-855 CE), who believed in Ahadith interpreting the Quran, felt the same way and said that he could never even think about it. Al-Qartabi (1214-1273 CE) has also referred to great Imams of the Malaki School to confirm that they held the same position. An Ijma (consensus) of scholars cannot endorse Naskh either because it has no precedence in the Quran, Hadith, Sunnah or the history of Islam. Ibne Hazam (994-1064 CE) was initially in its favour, but soon after retracted his opinion. Similarly, if we start using the instrument of Islamic logic to abrogate Quranic verses, it could turn into an endless farce. The Sufi jurist al-Sharani (1492-1565 CE) considered claims of abrogation to be the choice of narrow-minded jurists whose hearts God had not illuminated with his Light.

The rationalist scholars have always rejected Naskh as poor scholarship and on the grounds that the word of God cannot contain have contradictions. The focused denunciation, however, started in the 19th century when reformist like Shaikh Abduh, Sir Syed, and Rashid Rida (1865-1935 CE) highlighted it as invalid. Sir Syed received extreme hostility due to it and was called Kafir and Naturee among others things. Rationalist views about Naskh were maintained in the 20th century by prominent Islamic scholars including Muhammad Amin (Egypt), Aslam Jairajpuri, Allama Iqbal and his protégé Allama Parwez. The latter wrote “Tubweebul Quran” and “Qurani Faisalay”, which should have killed the whole issue academically. However, the most remarkable work on this topic is Tafseer Mansukh ul Quran (1974) by Rahmat Ullah Tariq. In his research spanned over 20 years, he has not only covered all the angles, but also discussed each ‘Mansukh’ verse and destroyed the proponents’ arguments by utilising their own references.