Alarming conditions necessitate measures that are out of the ordinary. The ugly face of misogyny needs a sharp blow before we can even cause a dent in the longstanding mindsets and the soaring frequency of patriarchal transgressions that victimize women in multiple ways every hour of the day.

How many of us have ever witnessed rape or met a survivor after the gruesome assault, or personally known a sufferer of domestic abuse? Probably few. Visualize the impact of getting to witness the ensuing trauma of one of these victims, perhaps, an experience that would haunt us for the rest of our lives.

To counter these ‘horrors’ of misguided patriarchy lurking among and around us and in order to challenge their ghastly outcomes, women need to pull off a horror show too; loud, forceful and daunting on these very roads, the very places that hum of that familiar fear that women feel with every breath while in public spaces. A fear that is so common that for most women, it is an accepted fact of life.

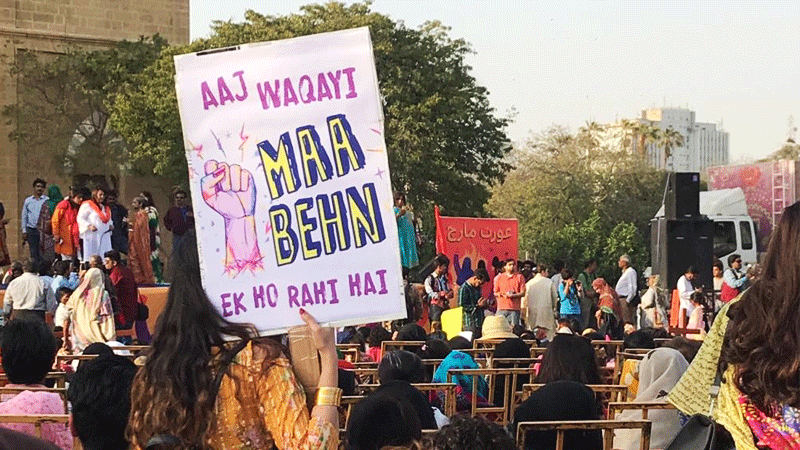

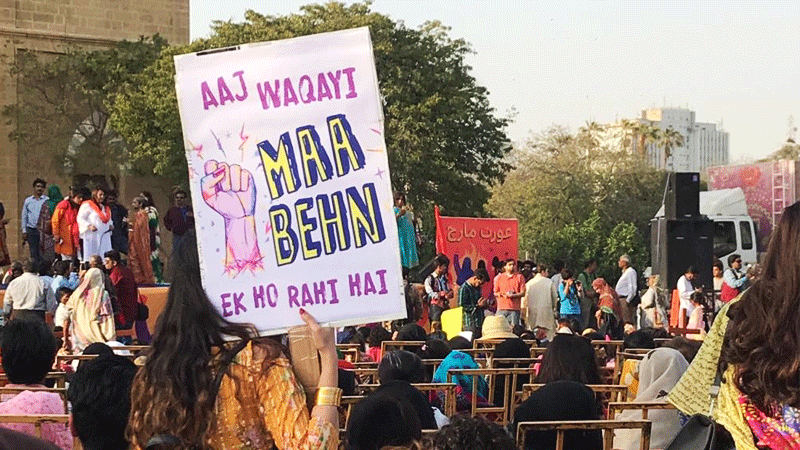

Rebellion is not about euphemizing, sugarcoating or being overly moderate, but when it comes to women, we are told to be so; hence, the shock at anything that is strident and vigorous like the Aurat March. These women and men, whom we see out on the streets, march and bellow for the harrowing existence of the rape survivor whom you and I have never seen, the harassment victim that we have never pacified and the underpaid female worker whom we have never deigned to offer help.

Numbers alone do not define rallies; nor are they solely sufficient, in changing attitudes and defying harmful norms. Marches and rallies do not have an impact if they fail to stir backlash for being radical and revisionist. Criticism and commentary is, hence, a gauge of the success of a march and the first step towards ensuring headway and achieving campaign goals.

How is it, then, that the Aurat March will not attract animosity for all the wrong reasons? Posters carried and slogans chanted at the last years’ marches drew never-ending contempt. Among the ones attacked were posters addressing unwanted sexual advances towards women, explicit and suggestive photos women receive from men online and the ones targeting the assumed “right way” for a woman to sit. The feminism of pleasure, namely sexual politics, bodily autonomy, agency over time and leisure, is always intimidating and considered ‘bad’ feminism, dubbed ‘immoral’ and ‘frivolous’ by antagonists. As opposed to the ‘good’ feminism of purpose that focuses on areas of health, education and women’s leadership.

This year too, marchers are being lambasted for going overboard in the ‘mannerism’ in which issues are expressed and communicated. While most, including women, agree with the manifesto and the causes that the annual march propagates, the strategy adopted in pursuit of those causes is debatable for them, especially for men and women who have internalized forces of patriarchy over time. They fail to see or don’t want to see that the marchers might be adopting purposive implementation of a strategy of revolt in order to effect a much-needed change in an obstinate social structure. Even if they do spot the willful strategy of revolt, critics argue that the gravity of the Aurat March messages is ‘lost in the melee.’ They feel that the ‘Aurat March would do well by taking a pause for some introspection and a public discourse,’ so that the gains of the march are not lost.

As Aurat March campaign communication is widely misunderstood, every March the same pattern is repeated in the aftermath of the demonstration, as explainers and elucidations pour in from the organizers, sometimes, bordering on resorting to language of appeasement. While one can understand how the arguments work to clear any misunderstandings, care must be taken not to pacify. Mariam Azeem, Director, Movement Support and Training at Rhize and an active part of the Aurat March says that in 2020, ‘marchers reflected on the criticism to develop new, more nuanced and culturally contextualized slogans. They even decided to send new slogans to the High Court for approval, in the form of a visible stamp, prior to the march, for added precaution.’

So, is there a need to rethink or rephrase Aurat March messages for better understanding? The rule of effective receiver-oriented communication is simple: whenever a message is not understood or misunderstood, the responsibility for the loss of meaning lies with the sender of the message. Add to this linear rule of communication the affects of cultural and social mores, the pre-conceived notions and long held misconceptions under which the Aurat March slogans are scrutinized, and we would know why the messages are such an eyesore. It is not bad choice of words that always makes these slogans controversial; it is the negative connotations attached to the chosen words that we, as a society, have to learn to unlearn. Connotative and colloquial meanings of terms such as ‘azadi’ that is a part of the most vociferous of the Aurat March chants, is a word that has always had a stereotype attached to it when it comes to the female gender.

And, hence, even though the march is not all about women’s lib, critics question what ‘type of liberation women want?’ They fail to see that the march is more about the blatant absence and violation of rights. They spot ‘obscenity and crudity’ in slogans and posters, but not in the act of a woman being groped in the marketplace, as such incidents are hardly reported, while young girls are taught to ignore male overtures and keep their mouths muzzled to avoid shameful publicity and dishonour. For every mouth shut by society, the march raises a howling, while we see the ‘objectionable’ howling but not the hushed mouth that necessitated the frantic response. Traditional masculinity has always benefitted from protecting these so-called cultural values that defy women’s freedom of expression.

Debuting on the International Women’s Day, 2018, the Aurat March was initially led by a group of young progressive feminists who received support from multiple women's rights organizations. Since then, the walk has demanded more accountability for violence against women and help for women who experience harassment in public spaces, at home, and in the workplace. It also rallies for economic justice, labour rights for women, recognition of women’s work in the care economy as meriting pay, maternity leave rights and daycare centers to ensure women's inclusion in the workforce. Having succeeded in mobilising a large number of people from all walks of life, with participants cutting across generation, gender and class divide, the march has managed to embrace women at the grassroots as well.

As feminism continues its journey through precarious times, we must consider carefully what narratives we are collectively consolidating and what solutions these will help generate for generations to come.

How many of us have ever witnessed rape or met a survivor after the gruesome assault, or personally known a sufferer of domestic abuse? Probably few. Visualize the impact of getting to witness the ensuing trauma of one of these victims, perhaps, an experience that would haunt us for the rest of our lives.

To counter these ‘horrors’ of misguided patriarchy lurking among and around us and in order to challenge their ghastly outcomes, women need to pull off a horror show too; loud, forceful and daunting on these very roads, the very places that hum of that familiar fear that women feel with every breath while in public spaces. A fear that is so common that for most women, it is an accepted fact of life.

Rebellion is not about euphemizing, sugarcoating or being overly moderate, but when it comes to women, we are told to be so; hence, the shock at anything that is strident and vigorous like the Aurat March. These women and men, whom we see out on the streets, march and bellow for the harrowing existence of the rape survivor whom you and I have never seen, the harassment victim that we have never pacified and the underpaid female worker whom we have never deigned to offer help.

Numbers alone do not define rallies; nor are they solely sufficient, in changing attitudes and defying harmful norms. Marches and rallies do not have an impact if they fail to stir backlash for being radical and revisionist. Criticism and commentary is, hence, a gauge of the success of a march and the first step towards ensuring headway and achieving campaign goals.

How is it, then, that the Aurat March will not attract animosity for all the wrong reasons? Posters carried and slogans chanted at the last years’ marches drew never-ending contempt. Among the ones attacked were posters addressing unwanted sexual advances towards women, explicit and suggestive photos women receive from men online and the ones targeting the assumed “right way” for a woman to sit. The feminism of pleasure, namely sexual politics, bodily autonomy, agency over time and leisure, is always intimidating and considered ‘bad’ feminism, dubbed ‘immoral’ and ‘frivolous’ by antagonists. As opposed to the ‘good’ feminism of purpose that focuses on areas of health, education and women’s leadership.

This year too, marchers are being lambasted for going overboard in the ‘mannerism’ in which issues are expressed and communicated. While most, including women, agree with the manifesto and the causes that the annual march propagates, the strategy adopted in pursuit of those causes is debatable for them, especially for men and women who have internalized forces of patriarchy over time. They fail to see or don’t want to see that the marchers might be adopting purposive implementation of a strategy of revolt in order to effect a much-needed change in an obstinate social structure. Even if they do spot the willful strategy of revolt, critics argue that the gravity of the Aurat March messages is ‘lost in the melee.’ They feel that the ‘Aurat March would do well by taking a pause for some introspection and a public discourse,’ so that the gains of the march are not lost.

As Aurat March campaign communication is widely misunderstood, every March the same pattern is repeated in the aftermath of the demonstration, as explainers and elucidations pour in from the organizers, sometimes, bordering on resorting to language of appeasement. While one can understand how the arguments work to clear any misunderstandings, care must be taken not to pacify. Mariam Azeem, Director, Movement Support and Training at Rhize and an active part of the Aurat March says that in 2020, ‘marchers reflected on the criticism to develop new, more nuanced and culturally contextualized slogans. They even decided to send new slogans to the High Court for approval, in the form of a visible stamp, prior to the march, for added precaution.’

So, is there a need to rethink or rephrase Aurat March messages for better understanding? The rule of effective receiver-oriented communication is simple: whenever a message is not understood or misunderstood, the responsibility for the loss of meaning lies with the sender of the message. Add to this linear rule of communication the affects of cultural and social mores, the pre-conceived notions and long held misconceptions under which the Aurat March slogans are scrutinized, and we would know why the messages are such an eyesore. It is not bad choice of words that always makes these slogans controversial; it is the negative connotations attached to the chosen words that we, as a society, have to learn to unlearn. Connotative and colloquial meanings of terms such as ‘azadi’ that is a part of the most vociferous of the Aurat March chants, is a word that has always had a stereotype attached to it when it comes to the female gender.

And, hence, even though the march is not all about women’s lib, critics question what ‘type of liberation women want?’ They fail to see that the march is more about the blatant absence and violation of rights. They spot ‘obscenity and crudity’ in slogans and posters, but not in the act of a woman being groped in the marketplace, as such incidents are hardly reported, while young girls are taught to ignore male overtures and keep their mouths muzzled to avoid shameful publicity and dishonour. For every mouth shut by society, the march raises a howling, while we see the ‘objectionable’ howling but not the hushed mouth that necessitated the frantic response. Traditional masculinity has always benefitted from protecting these so-called cultural values that defy women’s freedom of expression.

Debuting on the International Women’s Day, 2018, the Aurat March was initially led by a group of young progressive feminists who received support from multiple women's rights organizations. Since then, the walk has demanded more accountability for violence against women and help for women who experience harassment in public spaces, at home, and in the workplace. It also rallies for economic justice, labour rights for women, recognition of women’s work in the care economy as meriting pay, maternity leave rights and daycare centers to ensure women's inclusion in the workforce. Having succeeded in mobilising a large number of people from all walks of life, with participants cutting across generation, gender and class divide, the march has managed to embrace women at the grassroots as well.

As feminism continues its journey through precarious times, we must consider carefully what narratives we are collectively consolidating and what solutions these will help generate for generations to come.