Eminent novelist Abdullah Hussein shares his birthday with Pakistan.

On 14 August in 2009 (the year when I interviewed him), he turned seventy-eight. Abdullah Hussein had a slightly eccentric lifestyle. Although not too well, he lived on his own in Lahore. His daughter lived next door, but he performed all his household chores by himself, including cooking his own food, etc. To my knowledge, he was the only man who wrote and published fiction in both Urdu and English. He was also probably the only writer who had been offered State awards by every government since 1984 but turned them down. Funnily, among all my acquaintances he was one man who did not have a cell-phone and got by on a single landline.

Abdullah Hussein was averse to giving interviews to the press, but after much persuasion agreed to talk to me for Herald in 2009.

Here is how our conversation went by:

Are you writing any new novel these days?

Abdullah Hussein: I have just finished writing a novel in English about Afghanistan, which is with my agent in London. I have now started writing the second part of my last Urdu novel ‘Nadaar log’.

How do you choose your plots, characters, locales etc.?

AH: Let’s just say that they choose me.

Do you think you still enjoy the most popular serious novelist stature that you acquired overnight after publishing your first novel ‘Udas Naslein’?

AH: I didn’t acquire it, it was thrust upon me, and it still sticks, going by what my publisher says.

Why is there such a long gap between ‘Udas Naslein’ and your further novels like ‘Ba’gh, Qaid, Nadaar Log, and novellas like Nasheb, Raat and Wapsi ka Safar’?

AH: Three years after publishing my first novel, I left for Britain and mulled over things for some years before I picked up the pen again.

Do you regret not having stayed in Pakistan? Had you done so you could have gathered a group of friends and writers around you, started a magazine and become an institution, like some others have done.

AH: It’s better to write something that lasts for fifty years than become an institution which falls apart after you are gone. It is also better to be a small fish in a big pond, and even if you don’t make it in the end, at least you have the pleasure of running with the best pack.

In your novel ‘Ba’gh’, is it incidental that you chose the locale of Kashmir, or you wanted to highlight the freedom struggle of Kashmir?

AH: Nothing to do with freedom struggle. I was writing about the human condition. Like ‘Udas Naslein’, where the daughter of a nawab marries a poor peasant, ‘Ba’agh’ is also a love story.

The two themes of the novel are love and justice. What is incidental is that I gave a different version of history about an important event in our country, which was validated several years later when ‘Operation Gibraltar’ was revealed. It gives me a great deal of satisfaction, and should be a matter of pride for all fiction writers, that the event was first exposed in fiction. In a more advanced country, the publication of a novel like this would have created a furore. Over here, no-one even understood the significance of it.

After reading ‘Nadaar Log’ one gets the impression that you were one of the few Pakistanis who had access to Hamood-ur-Rehman Commission Report before it was published.

AH: One of my sources was the great researcher Ahmad Salim, and I gave him, and others, due credit at the beginning of the novel.

Why is somber pessimism a dominant feature of all your characters? Is it part of your personality?

AH: I have no such personality defects. I like to think that I am a person of cheerful disposition. But as I said before, I write about the human condition.

How was your own translation of ‘Udas Naslein’ (‘The Weary Generations’) received in the West?

AH: Very well. All the heavyweight papers and literary magazines reviewed it positively. Too numerous to quote, the one that pleased me most was a review in the Sunday Times by John Spurling (himself a novelist) who wrote, among other things, “. . . this powerful, subtle novel is as fresh today as it must have been forty years ago . . .” This is the supreme test of any work of art – the test of time.

You have also written two novels in English. Do you feel at ease writing in English, and why do you write in English?

AH: Regardless of how we brag about our Urdu, it is only in English that one gets worldwide distribution and readers. Several years after their publication, my English novels are still being read from Australia to America.

Why have you consistently refused to accept State awards?

AH: Corrupt bureaucrats, Generals, politicians and other low life get not only their tamghas but residential and agricultural lands, while they give some cheap tamghas and a few thousand rupees to writers and send them home. It insults my sensibility. Unless they provide decent income for life to those who receive awards, I want to be no part of this injustice.

Have you been impressed by any writer of Urdu fiction?

AH: I can say without qualification that Quratulain Hyder was, and remains, the best novelist in Urdu.

All your work, in one way or other, is about politics. Why?

AH: You can’t escape politics. If there is a ‘khadda (pothole)’ outside your door and one day you fall into it and break your leg, it is politics, because despite many requests by the residents, the local authorities failed to fill it. From this small incident to the biggest events, politics encroaches upon all aspects of life. I am engrossed not so much in politics as in justice, which is directly linked to politics, and by extension, to the rulers. All our governments have been corrupt and unjust, but what literally takes the cake is the present one. We used to say that we are being ruled by our inferiors, but now we are being ruled by criminals. I go abroad and see that the name of our highest leaders is dirt in the international community. I am not ashamed of being a Pakistani, but I am no longer proud of being one. Without justice, we become savages.

In the literary world, there are controversies and jealousies. Have you ever faced such a situation?

AH: There have been a few brickbats, some below the belt by nobodies, but overall, people have been very kind to me.

Why do you think no great works of literature are being produced now like they were written during the first third of Pakistan's life?

AH: Who wants to sit at a desk for hours staring at a blank page trying to write a decent line to communicate with unseen readers when there are so many available avenues for instant communication as Facebook and the Internet chatlines and those of quick gratification like Television? I'm surprised that more men and women novelists don't go mad than they do. I think the answer is that they are probably already mad before they started. It is a labour of love. However, I have recently read two fine novels by Athar Beg, so there are still some people - Abhi kuchh log baqi hain jahan mein.

What about 'Kai Chand Thay Sar-e- Asman" by Sham ur Rehman Farroqi?

AH: I haven't read it.

How do you look at Mohammad Hanif's Novel "The Case of Exploding Mangoes." Then there is novel of Danayal Moinuddin.. Earlier Mohsin Hamid and Nadeem Aslam also wrote novels?

AH: I am no oracle, let the readers make up their own mind about individual writers.

The interview was originally published in Herald in 2009 and has been reproduced to pay homage to literary legend Abdullah Hussein

On 14 August in 2009 (the year when I interviewed him), he turned seventy-eight. Abdullah Hussein had a slightly eccentric lifestyle. Although not too well, he lived on his own in Lahore. His daughter lived next door, but he performed all his household chores by himself, including cooking his own food, etc. To my knowledge, he was the only man who wrote and published fiction in both Urdu and English. He was also probably the only writer who had been offered State awards by every government since 1984 but turned them down. Funnily, among all my acquaintances he was one man who did not have a cell-phone and got by on a single landline.

Abdullah Hussein was averse to giving interviews to the press, but after much persuasion agreed to talk to me for Herald in 2009.

Here is how our conversation went by:

Are you writing any new novel these days?

Abdullah Hussein: I have just finished writing a novel in English about Afghanistan, which is with my agent in London. I have now started writing the second part of my last Urdu novel ‘Nadaar log’.

How do you choose your plots, characters, locales etc.?

AH: Let’s just say that they choose me.

Do you think you still enjoy the most popular serious novelist stature that you acquired overnight after publishing your first novel ‘Udas Naslein’?

AH: I didn’t acquire it, it was thrust upon me, and it still sticks, going by what my publisher says.

Cover of Abdullah Hussein's novel 'Udaas Naaslain' (Source: googlereads)

Why is there such a long gap between ‘Udas Naslein’ and your further novels like ‘Ba’gh, Qaid, Nadaar Log, and novellas like Nasheb, Raat and Wapsi ka Safar’?

AH: Three years after publishing my first novel, I left for Britain and mulled over things for some years before I picked up the pen again.

Do you regret not having stayed in Pakistan? Had you done so you could have gathered a group of friends and writers around you, started a magazine and become an institution, like some others have done.

AH: It’s better to write something that lasts for fifty years than become an institution which falls apart after you are gone. It is also better to be a small fish in a big pond, and even if you don’t make it in the end, at least you have the pleasure of running with the best pack.

In your novel ‘Ba’gh’, is it incidental that you chose the locale of Kashmir, or you wanted to highlight the freedom struggle of Kashmir?

AH: Nothing to do with freedom struggle. I was writing about the human condition. Like ‘Udas Naslein’, where the daughter of a nawab marries a poor peasant, ‘Ba’agh’ is also a love story.

Ba'agh novel written by Abdullah Hussein (Source: googlereads)

The two themes of the novel are love and justice. What is incidental is that I gave a different version of history about an important event in our country, which was validated several years later when ‘Operation Gibraltar’ was revealed. It gives me a great deal of satisfaction, and should be a matter of pride for all fiction writers, that the event was first exposed in fiction. In a more advanced country, the publication of a novel like this would have created a furore. Over here, no-one even understood the significance of it.

After reading ‘Nadaar Log’ one gets the impression that you were one of the few Pakistanis who had access to Hamood-ur-Rehman Commission Report before it was published.

AH: One of my sources was the great researcher Ahmad Salim, and I gave him, and others, due credit at the beginning of the novel.

Why is somber pessimism a dominant feature of all your characters? Is it part of your personality?

AH: I have no such personality defects. I like to think that I am a person of cheerful disposition. But as I said before, I write about the human condition.

How was your own translation of ‘Udas Naslein’ (‘The Weary Generations’) received in the West?

AH: Very well. All the heavyweight papers and literary magazines reviewed it positively. Too numerous to quote, the one that pleased me most was a review in the Sunday Times by John Spurling (himself a novelist) who wrote, among other things, “. . . this powerful, subtle novel is as fresh today as it must have been forty years ago . . .” This is the supreme test of any work of art – the test of time.

You have also written two novels in English. Do you feel at ease writing in English, and why do you write in English?

AH: Regardless of how we brag about our Urdu, it is only in English that one gets worldwide distribution and readers. Several years after their publication, my English novels are still being read from Australia to America.

Why have you consistently refused to accept State awards?

AH: Corrupt bureaucrats, Generals, politicians and other low life get not only their tamghas but residential and agricultural lands, while they give some cheap tamghas and a few thousand rupees to writers and send them home. It insults my sensibility. Unless they provide decent income for life to those who receive awards, I want to be no part of this injustice.

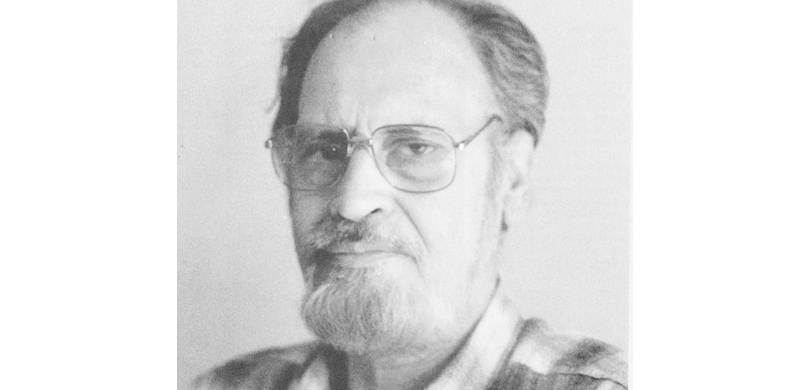

Image of Abdullah Hussein speaking at an event

Have you been impressed by any writer of Urdu fiction?

AH: I can say without qualification that Quratulain Hyder was, and remains, the best novelist in Urdu.

All your work, in one way or other, is about politics. Why?

AH: You can’t escape politics. If there is a ‘khadda (pothole)’ outside your door and one day you fall into it and break your leg, it is politics, because despite many requests by the residents, the local authorities failed to fill it. From this small incident to the biggest events, politics encroaches upon all aspects of life. I am engrossed not so much in politics as in justice, which is directly linked to politics, and by extension, to the rulers. All our governments have been corrupt and unjust, but what literally takes the cake is the present one. We used to say that we are being ruled by our inferiors, but now we are being ruled by criminals. I go abroad and see that the name of our highest leaders is dirt in the international community. I am not ashamed of being a Pakistani, but I am no longer proud of being one. Without justice, we become savages.

In the literary world, there are controversies and jealousies. Have you ever faced such a situation?

AH: There have been a few brickbats, some below the belt by nobodies, but overall, people have been very kind to me.

Why do you think no great works of literature are being produced now like they were written during the first third of Pakistan's life?

AH: Who wants to sit at a desk for hours staring at a blank page trying to write a decent line to communicate with unseen readers when there are so many available avenues for instant communication as Facebook and the Internet chatlines and those of quick gratification like Television? I'm surprised that more men and women novelists don't go mad than they do. I think the answer is that they are probably already mad before they started. It is a labour of love. However, I have recently read two fine novels by Athar Beg, so there are still some people - Abhi kuchh log baqi hain jahan mein.

What about 'Kai Chand Thay Sar-e- Asman" by Sham ur Rehman Farroqi?

AH: I haven't read it.

How do you look at Mohammad Hanif's Novel "The Case of Exploding Mangoes." Then there is novel of Danayal Moinuddin.. Earlier Mohsin Hamid and Nadeem Aslam also wrote novels?

AH: I am no oracle, let the readers make up their own mind about individual writers.

The interview was originally published in Herald in 2009 and has been reproduced to pay homage to literary legend Abdullah Hussein