The “thin-centered” political repertoire known as populism, lacking the necessary ideological thickness to be called an ideology, became a zeitgeist for politics around the globe in the last decade. While taking advantage of public sentiments developing as a result of disenchantment from the mainstream political setup in various countries, since the 2008 financial crisis, the rise of right-wing populism was a wake-up call from slumber and a chance for a theoretical redressal for two different groups of scholars.

It was a chance for a theoretical remedy for scholars who after the end of Cold War perceived a victory of capitalism and democracy: they were either theorizing this historical juncture as “end of history”; were presenting a celebratory account of liberal democracies as unscathable entities (a perfect alternative to “oppressive” communism); or were just busy eschewing and restricting the burgeoning problem of the public’s political and economic disenchantment to “cultural and religious conflicts.”

After the rise of right-wing populists around the globe who took advantage of this political and economic crisis, democracies experienced remarkable “backsliding” and became more exclusionary in nature. As ever, the same scholars, fearing that their theories might be tossed into the dustbin of history, were busy rectifying or explaining their works as “time-bound or still relevant”. The rise of right-wing populism became an eye-opener for other groups of scholars who, with their limited predictive nature of scholarly contribution, did not see the phenomenon coming at all, and only started theorizing it when it was in its full bloom.

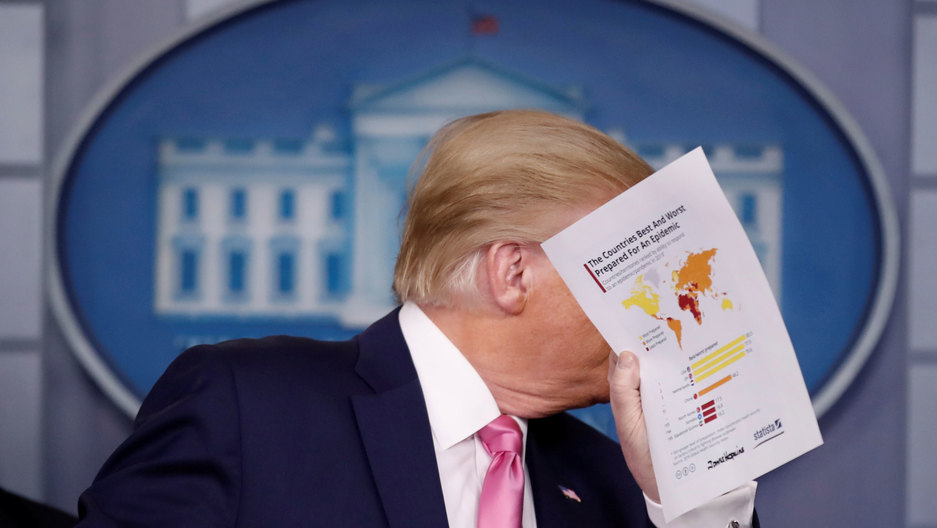

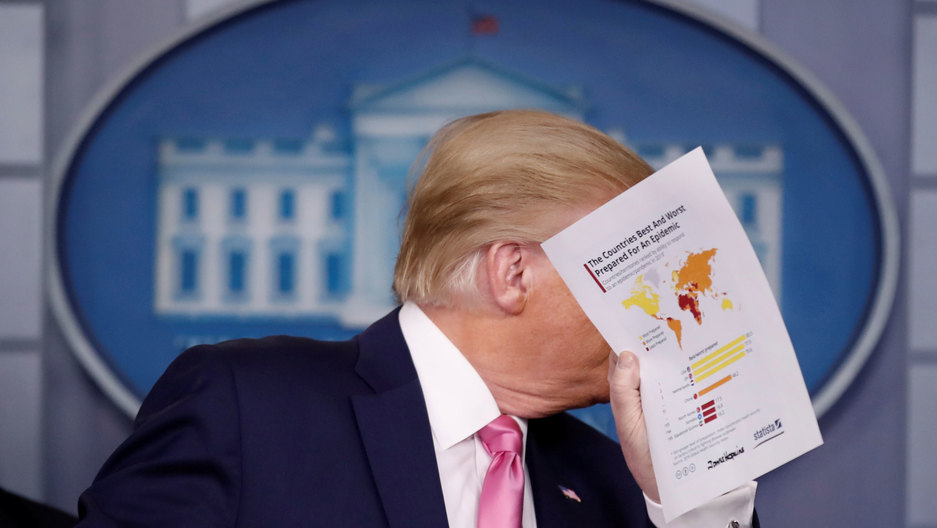

Mabel Berezin explains this academic upsurge surrounding the subject through a Google engram, which shows a sharp rise in the discussion and scholarly contributions on the subject around 2016, with the victory of Donald Trump in the Unites States. Some called it “a threat and corrective for democracy” and others merely saw it as a fashionable buzzword being used to craft fancy academic titles, or a “discursive or stylistic repertoire” not to be taken seriously. This latter group of scholars produced a substantial body of literature on the subject.

A common consensus which emerged from this swath of research was the variegated and differential impact that right-wing populists were having on different democracies and the governance under them in the world – and how regime type as a conditioning factor would be important to assess the repercussions of the phenomenon on a particular state.

To put it more simply, the damage perpetrated through exclusivist political demagoguery in government would be dependent on the ability of the political institutions to sustain it.

The more liberal and open the democracy, the less would be the damage to democratic values and the less pronounced would be the impact on governance. It was analyzed that institutionalized liberal democracies with increased democratic checks, independent judiciaries and relatively active civil society – like the one in United States and some in Western Europe – would be spared some of the worst aspects of the populist onslaught and a major transition in the governance is unlikely. However, minorities and already-marginalized groups could be in a precarious situation. This was proven through increased hate crimes against minorities in United States ever since Donald Trump’s entry to the office and curtailed liberties and rise in anti-migrant sentiments in the Netherlands, France and Germany.

In contrast, Central and Eastern Europe, Hungary and Balkan states like Serbia with already low Freedom House scores and a more susceptible democratic setting to right-wing populism, experienced a larger decline in democratic values and passed legislation which made these states more authoritarian in nature.

India, which has been on a democratic downhill in general after the death of Nehru, has experienced a sharp deviation from the Nehruvian essence of its democracy post-2014, ever since the Hindu nationalist government of BJP came to power, which has been carefully moving the country towards a Hindu Rashtra.

Surprisingly, other than op-eds there is dearth of serious work that assesses military-led hybrid regimes like Pakistan and how populism of leaders such as Imran Khan would be detrimental or fruitful given the under-nourished democratic setting. The op-ed commentaries in the past had predicted that “Naya Pakistan” was nothing more than populist rhetoric, and another episode of political engineering that has been implemented many times in the ‘land of the pure’. Given the way the government has performed in its first two years, the hollowness of Imran Khan's rhetoric has been confirmed.

But where do the scholarly insights about regime-type-specific impact of political demagoguery stand – after Covid-19 morphed into a pandemic?

Some pundits have been busy predicting that the pandemic might become the death of this ideologically clueless phenomenon, seeing the way populist governments have dealt with the pandemic overall, others have warned about crisis coming in handy for populist leaders, who could use it for more authoritarian steps and become stronger. But one interesting analogous picture which the pandemic has presented across borders – which so far did not yet catch the eye of scholarly research – is that it has unveiled the ideological and governance cluelessness of populist leaders across the democracies and semi-authoritarian regimes over the world. The discussion has transcended the nature of the regimes, the “democratic” standing of your Freedom House scores and how capable your state is to sustain the populist onslaught.

From US, UK to Brazil, India and Pakistan, and among some European states, the callous response of populists and ill-performance of these governments in the pandemic has uncovered the true nature of their politics – beneath which lies false promises and hollow rhetoric all couched in neoliberal emancipatory jargon and cosmetic policies.

In the pandemic, the importance of regime-type sounds an obsolete scholarly understanding. Across borders, we see an image of incompetence and ill-preparedness, where sometimes these leaders, at the behest of the lives of the ordinary people, were seen sitting on the bandwagon of conspiracy theories which call the pandemic a hoax, and sometimes it becomes “a normal flu” which would go away in few days. The impact is disproportionately worse for developing countries like Pakistan and India. It would be interesting to see in the coming days as to how the scholarly fraternity which usually comes under criticism for the inflated use of term ‘populism,’ understands and dissects this homogenizing impact of populist governments across the globe.

In contrast, the states which have fared well in dealing with the crisis are far from being labelled as populist.

It is time for those with the alternative vision who envision a world free of political clowns to make the pandemic a juncture for shifting towards more pro-people governments and a political vision that is un-succumbing, unyielding and free from the superficial rhetoric of populist leaders. Making the pandemic a point of realization, those with an alternative vision should use the disastrous performance of populist leaders as a litmus test of their incompetence, for launching an alternative vision.

It would also be a good time to politically educate the masses so as to unveil the difference between shallow rhetoric and a political vision backed with solid policy planning.

It was a chance for a theoretical remedy for scholars who after the end of Cold War perceived a victory of capitalism and democracy: they were either theorizing this historical juncture as “end of history”; were presenting a celebratory account of liberal democracies as unscathable entities (a perfect alternative to “oppressive” communism); or were just busy eschewing and restricting the burgeoning problem of the public’s political and economic disenchantment to “cultural and religious conflicts.”

After the rise of right-wing populists around the globe who took advantage of this political and economic crisis, democracies experienced remarkable “backsliding” and became more exclusionary in nature. As ever, the same scholars, fearing that their theories might be tossed into the dustbin of history, were busy rectifying or explaining their works as “time-bound or still relevant”. The rise of right-wing populism became an eye-opener for other groups of scholars who, with their limited predictive nature of scholarly contribution, did not see the phenomenon coming at all, and only started theorizing it when it was in its full bloom.

Mabel Berezin explains this academic upsurge surrounding the subject through a Google engram, which shows a sharp rise in the discussion and scholarly contributions on the subject around 2016, with the victory of Donald Trump in the Unites States. Some called it “a threat and corrective for democracy” and others merely saw it as a fashionable buzzword being used to craft fancy academic titles, or a “discursive or stylistic repertoire” not to be taken seriously. This latter group of scholars produced a substantial body of literature on the subject.

A common consensus which emerged from this swath of research was the variegated and differential impact that right-wing populists were having on different democracies and the governance under them in the world – and how regime type as a conditioning factor would be important to assess the repercussions of the phenomenon on a particular state.

To put it more simply, the damage perpetrated through exclusivist political demagoguery in government would be dependent on the ability of the political institutions to sustain it.

The more liberal and open the democracy, the less would be the damage to democratic values and the less pronounced would be the impact on governance. It was analyzed that institutionalized liberal democracies with increased democratic checks, independent judiciaries and relatively active civil society – like the one in United States and some in Western Europe – would be spared some of the worst aspects of the populist onslaught and a major transition in the governance is unlikely. However, minorities and already-marginalized groups could be in a precarious situation. This was proven through increased hate crimes against minorities in United States ever since Donald Trump’s entry to the office and curtailed liberties and rise in anti-migrant sentiments in the Netherlands, France and Germany.

In contrast, Central and Eastern Europe, Hungary and Balkan states like Serbia with already low Freedom House scores and a more susceptible democratic setting to right-wing populism, experienced a larger decline in democratic values and passed legislation which made these states more authoritarian in nature.

India, which has been on a democratic downhill in general after the death of Nehru, has experienced a sharp deviation from the Nehruvian essence of its democracy post-2014, ever since the Hindu nationalist government of BJP came to power, which has been carefully moving the country towards a Hindu Rashtra.

Surprisingly, other than op-eds there is dearth of serious work that assesses military-led hybrid regimes like Pakistan and how populism of leaders such as Imran Khan would be detrimental or fruitful given the under-nourished democratic setting. The op-ed commentaries in the past had predicted that “Naya Pakistan” was nothing more than populist rhetoric, and another episode of political engineering that has been implemented many times in the ‘land of the pure’. Given the way the government has performed in its first two years, the hollowness of Imran Khan's rhetoric has been confirmed.

But where do the scholarly insights about regime-type-specific impact of political demagoguery stand – after Covid-19 morphed into a pandemic?

Some pundits have been busy predicting that the pandemic might become the death of this ideologically clueless phenomenon, seeing the way populist governments have dealt with the pandemic overall, others have warned about crisis coming in handy for populist leaders, who could use it for more authoritarian steps and become stronger. But one interesting analogous picture which the pandemic has presented across borders – which so far did not yet catch the eye of scholarly research – is that it has unveiled the ideological and governance cluelessness of populist leaders across the democracies and semi-authoritarian regimes over the world. The discussion has transcended the nature of the regimes, the “democratic” standing of your Freedom House scores and how capable your state is to sustain the populist onslaught.

From US, UK to Brazil, India and Pakistan, and among some European states, the callous response of populists and ill-performance of these governments in the pandemic has uncovered the true nature of their politics – beneath which lies false promises and hollow rhetoric all couched in neoliberal emancipatory jargon and cosmetic policies.

In the pandemic, the importance of regime-type sounds an obsolete scholarly understanding. Across borders, we see an image of incompetence and ill-preparedness, where sometimes these leaders, at the behest of the lives of the ordinary people, were seen sitting on the bandwagon of conspiracy theories which call the pandemic a hoax, and sometimes it becomes “a normal flu” which would go away in few days. The impact is disproportionately worse for developing countries like Pakistan and India. It would be interesting to see in the coming days as to how the scholarly fraternity which usually comes under criticism for the inflated use of term ‘populism,’ understands and dissects this homogenizing impact of populist governments across the globe.

In contrast, the states which have fared well in dealing with the crisis are far from being labelled as populist.

It is time for those with the alternative vision who envision a world free of political clowns to make the pandemic a juncture for shifting towards more pro-people governments and a political vision that is un-succumbing, unyielding and free from the superficial rhetoric of populist leaders. Making the pandemic a point of realization, those with an alternative vision should use the disastrous performance of populist leaders as a litmus test of their incompetence, for launching an alternative vision.

It would also be a good time to politically educate the masses so as to unveil the difference between shallow rhetoric and a political vision backed with solid policy planning.