Online learning, as discussed in my previous article, has been embraced by various educational institutions especially universities in Pakistan. The universities’ administrative staff and faculty faced serious issues related to, for example, internet connectivity and virtual data space ─ which stirred institutional efforts to experiment various software such as Zoom and/or Google Meet. Thus, many universities, both in public and private sector, were able to move ahead with online classes though issues related to internet connectivity and, in certain areas, power outages hampered online learning processes for the students living in the far-flung areas such as tribal districts of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and/or Gilgit-Baltistan. However, to help such students, universities observed by the author allowed for pre-recorded lectures that students could consult for exams.

In addition, online attendance was not made mandatory. Though this seemed a reasonable way-out given the pandemic. However, it backfired as it resulted in low attendance, low-level of students’ participation and delayed submission of assignments due to changing deadlines. It is also an attitudinal problem because our students have been made, in normal circumstances, to meet deadlines. Additionally, whenever one inquired into causes of delayed submissions, the cumulative response was based on poor internet connection ─ and this is something which is really hard to verify. Ironically, however, when the same universities set deadlines for final exam in spring 2020, the majority of students somehow met the deadlines by going online, using, for example, google classroom and uploading pdf/MS Word files. This variance in students’ behavior is a cause for concern for long-term policy formulation for online learning.

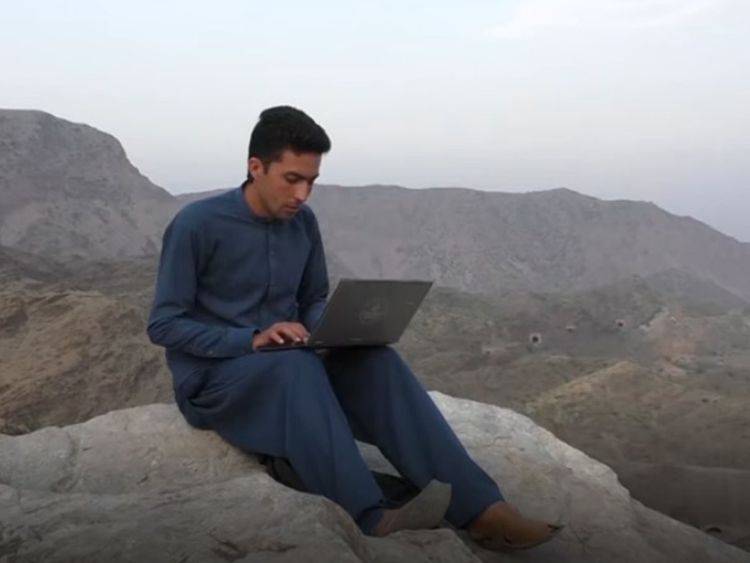

Nonetheless my observation is that the digital divide is real and pervasive in Pakistan and when faced with deadlines, students living in remote areas ─ with genuine internet and electricity issues ─ moved to their relatives and friends in major cities such as Peshawar or Multan to avail comparatively stable internet connectivity and upload data in time. Moreover, based on my personal feedback from students living in GB, former FATA, AJK, Balochistan and rural areas of Sindh, KP and Punjab, they faced severe internet, electricity and economic problems which really disturbed their studies and, in cases, grades. Let me cite here a couple of cases of students from far-flung rural/hilly areas. A male BS student from a small village from DG Khan emailed me to seek permission to submit a handwritten final exam since he did not have a laptop. In another case, a woman student from Gilgit city sent an email and informed that it took her five hours to ‘send’ me that simple email which normally needed a click.

It's a pity despite hullabaloo on the part of cellular companies such as Ufone and/or Jazz/Warid, they have miserably failed to provide a stable 3G service to the rural/hilly areas of the country. This digital divide is coupled with long-hours of unscheduled load shedding in most of these areas. The author, residing for past four months in a small village in central Punjab due to Covid-19, has faced issues of poor internet connectivity and unscheduled power outages on the part of GEPCO which despite maintaining ‘zero’ load shedding on its website has been playing havoc with rural people especially children and elderly.

The problem is further compounded by the fact that certain universities opted for ‘live’ lectures for the ongoing summer semester, while ignoring issues related to load shedding and unstable internet. Pre-recorded option along with live sessions could have been an effective strategy in this respect. Little wonder, students’ attendance (non-mandatory, in some cases) is still low in live sessions know to the author; most of them even do not like to speak up but rather rely on the ‘chat’ option ─ which is a lower form of participation on an online forum. Students should speak up, and participate visibly, not passively, to provide feedback as well as internalize modalities of virtual classroom, which would be useful tools for them later in their professional lives.

Last but not the least, due to absence of online education policy, educational institutions from nursery schools to universities are struggling technologically, infrastructure-wise, socially and commercially. In this respect, students, who were not familiarized with online education bore the brunt in terms of facing a unique context grounded in an uneven environment which structurally privilege the possessed and prey on the poor. Thus, the rich and resourceful living in the DHAs and Bahira Towns have little internet and electricity problems for students and faculty since both share the same class whereas the poor of Pakistan ─ living in urban slums, unplanned towns and unfacilitated villages─ are further disadvantaged in terms of poor internet, load shedding, high tariffs, price hike, growing crimes and, overall, hopelessness speared up by Covid-19.

In a country like ours where more than 25 million kids are out of school on account of abject poverty, the coronavirus has further impacted the same class whose school-going children and teenagers are not provided with ‘online’ classes by the government due to lack of political will whereas the progeny of the elite is availing online learning in cozy settings. Covid-19 has certainly exposed the existing structural inequalities in not just education but also technology, economy and the society.

In addition, online attendance was not made mandatory. Though this seemed a reasonable way-out given the pandemic. However, it backfired as it resulted in low attendance, low-level of students’ participation and delayed submission of assignments due to changing deadlines. It is also an attitudinal problem because our students have been made, in normal circumstances, to meet deadlines. Additionally, whenever one inquired into causes of delayed submissions, the cumulative response was based on poor internet connection ─ and this is something which is really hard to verify. Ironically, however, when the same universities set deadlines for final exam in spring 2020, the majority of students somehow met the deadlines by going online, using, for example, google classroom and uploading pdf/MS Word files. This variance in students’ behavior is a cause for concern for long-term policy formulation for online learning.

Nonetheless my observation is that the digital divide is real and pervasive in Pakistan and when faced with deadlines, students living in remote areas ─ with genuine internet and electricity issues ─ moved to their relatives and friends in major cities such as Peshawar or Multan to avail comparatively stable internet connectivity and upload data in time. Moreover, based on my personal feedback from students living in GB, former FATA, AJK, Balochistan and rural areas of Sindh, KP and Punjab, they faced severe internet, electricity and economic problems which really disturbed their studies and, in cases, grades. Let me cite here a couple of cases of students from far-flung rural/hilly areas. A male BS student from a small village from DG Khan emailed me to seek permission to submit a handwritten final exam since he did not have a laptop. In another case, a woman student from Gilgit city sent an email and informed that it took her five hours to ‘send’ me that simple email which normally needed a click.

It's a pity despite hullabaloo on the part of cellular companies such as Ufone and/or Jazz/Warid, they have miserably failed to provide a stable 3G service to the rural/hilly areas of the country. This digital divide is coupled with long-hours of unscheduled load shedding in most of these areas. The author, residing for past four months in a small village in central Punjab due to Covid-19, has faced issues of poor internet connectivity and unscheduled power outages on the part of GEPCO which despite maintaining ‘zero’ load shedding on its website has been playing havoc with rural people especially children and elderly.

The problem is further compounded by the fact that certain universities opted for ‘live’ lectures for the ongoing summer semester, while ignoring issues related to load shedding and unstable internet. Pre-recorded option along with live sessions could have been an effective strategy in this respect. Little wonder, students’ attendance (non-mandatory, in some cases) is still low in live sessions know to the author; most of them even do not like to speak up but rather rely on the ‘chat’ option ─ which is a lower form of participation on an online forum. Students should speak up, and participate visibly, not passively, to provide feedback as well as internalize modalities of virtual classroom, which would be useful tools for them later in their professional lives.

Last but not the least, due to absence of online education policy, educational institutions from nursery schools to universities are struggling technologically, infrastructure-wise, socially and commercially. In this respect, students, who were not familiarized with online education bore the brunt in terms of facing a unique context grounded in an uneven environment which structurally privilege the possessed and prey on the poor. Thus, the rich and resourceful living in the DHAs and Bahira Towns have little internet and electricity problems for students and faculty since both share the same class whereas the poor of Pakistan ─ living in urban slums, unplanned towns and unfacilitated villages─ are further disadvantaged in terms of poor internet, load shedding, high tariffs, price hike, growing crimes and, overall, hopelessness speared up by Covid-19.

In a country like ours where more than 25 million kids are out of school on account of abject poverty, the coronavirus has further impacted the same class whose school-going children and teenagers are not provided with ‘online’ classes by the government due to lack of political will whereas the progeny of the elite is availing online learning in cozy settings. Covid-19 has certainly exposed the existing structural inequalities in not just education but also technology, economy and the society.