It is not an easy play for anyone to express resentment over the policies proposed and enacted by the govt authorities in Pakistan. Record shows that the stakes are high. Dissenters are often forced behind bars or to face other punitive setbacks.

The most recent victim of administrative harassment is the educationalist and student rights activist, Ammar Ali Jan. He mobilized students from public sector universities to primarily criticize the government’s unprecedented budget cuts in education sector. Minutes after his speech on the march day, Ammar was approached by law enforcement officials with arrest orders issued by the city’s deputy commissioner, awkwardly detailing that he was a threat to the civility of the country. The flare up between Ammar and the administration has resurfaced the question about the future of political dissent in the country.

This question is more important now than ever because all of the violations are happening under the watch of the incumbent prime minister, Imran Khan, who keenly fostered an impression to preserve freedom of speech during his electoral campaign. While he fell short on upholding his promise on a number of fronts, the worst part is that he does not even acknowledge pervasive media censorship when pointed out to him. Earlier this year in an interview with AlJazeera, he denied any infringement of speech, aggressively commenting that there was no evidence available.

In reality, journalists have had posited concerns about lack of media freedom and subsequent inability to cover domestic issues in considerable detail. Many journalists fear that they cannot report on the military’s political excursions because of the military’s inability to restrain anger and others talk about unexpected suspensions of their broadcasts by Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) to hinder political diversity in media.

Even for activists, a full out protest is not an option because there are no precedents in recent history where parties were able to successfully bargain with the government authorities. It could be a reason for the failure of counter culture movements to sway public opinion. Even the Aurat (women) march, which got incredible media spotlight, was able to mobilise women only in developed cities while largely underperformed in rural areas.

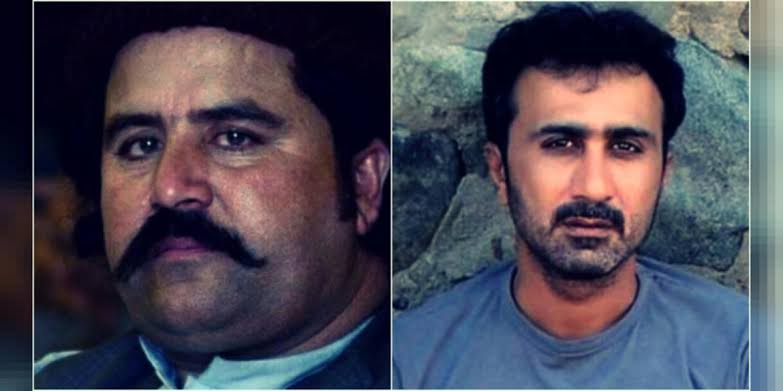

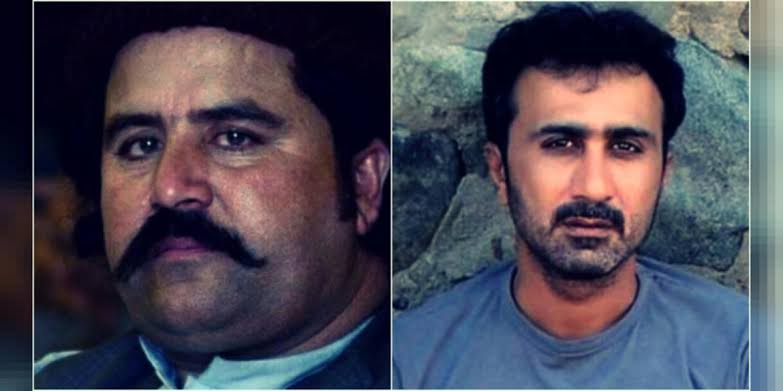

Protestors in rural areas, far off from the sight of media agencies to support their cause, are often encroached with predetermined judicial reviews. The case of Baba Jan is the prime example where the anti-terrorism authorities falsely convicted him along with his eleven fellow activists for the murder of two people. They were protesting for govt compensation for the affectees of a landslide in Attabbad village of Gilgit Baltistan, back in 2010.

People previously thought that a relatively safer way to express was online activism. Facebook users used to circulate memes on military’s involvement in the decision-making process and decried deteriorating conditions through posts on various social media platforms. However, the numbers plummeted after government approved a law in early February which gave it almost authoritarian powers to regulate the online media.

Under such circumstances, the future looks grim.

The most recent victim of administrative harassment is the educationalist and student rights activist, Ammar Ali Jan. He mobilized students from public sector universities to primarily criticize the government’s unprecedented budget cuts in education sector. Minutes after his speech on the march day, Ammar was approached by law enforcement officials with arrest orders issued by the city’s deputy commissioner, awkwardly detailing that he was a threat to the civility of the country. The flare up between Ammar and the administration has resurfaced the question about the future of political dissent in the country.

This question is more important now than ever because all of the violations are happening under the watch of the incumbent prime minister, Imran Khan, who keenly fostered an impression to preserve freedom of speech during his electoral campaign. While he fell short on upholding his promise on a number of fronts, the worst part is that he does not even acknowledge pervasive media censorship when pointed out to him. Earlier this year in an interview with AlJazeera, he denied any infringement of speech, aggressively commenting that there was no evidence available.

In reality, journalists have had posited concerns about lack of media freedom and subsequent inability to cover domestic issues in considerable detail. Many journalists fear that they cannot report on the military’s political excursions because of the military’s inability to restrain anger and others talk about unexpected suspensions of their broadcasts by Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) to hinder political diversity in media.

Even for activists, a full out protest is not an option because there are no precedents in recent history where parties were able to successfully bargain with the government authorities. It could be a reason for the failure of counter culture movements to sway public opinion. Even the Aurat (women) march, which got incredible media spotlight, was able to mobilise women only in developed cities while largely underperformed in rural areas.

Protestors in rural areas, far off from the sight of media agencies to support their cause, are often encroached with predetermined judicial reviews. The case of Baba Jan is the prime example where the anti-terrorism authorities falsely convicted him along with his eleven fellow activists for the murder of two people. They were protesting for govt compensation for the affectees of a landslide in Attabbad village of Gilgit Baltistan, back in 2010.

People previously thought that a relatively safer way to express was online activism. Facebook users used to circulate memes on military’s involvement in the decision-making process and decried deteriorating conditions through posts on various social media platforms. However, the numbers plummeted after government approved a law in early February which gave it almost authoritarian powers to regulate the online media.

Under such circumstances, the future looks grim.