An enforced disappearance is a particularly heinous crime, which involves multiple human rights violations, including breaches of the right to be protected against arbitrary deprivation of liberty, the right not to be subjected to torture or other inhumane, degrading or cruel treatment, the right to security, and the right to be protected under the law. The preamble to the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance clearly affirms the “extreme seriousness of enforced disappearance, which constitutes a crime and, in certain circumstances defined in international law, a crime against humanity”.

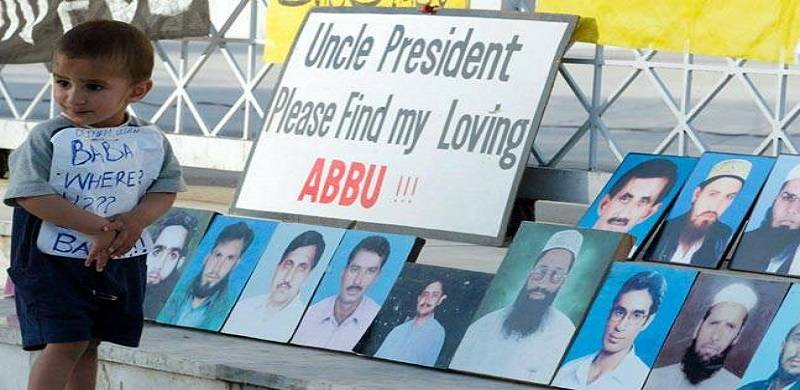

The seriousness of the crime can be seen in its “doubly paralyzing form of suffering” (Kirsten Anderson, 2006). On a first level, through removal of the victim from the protection of the law and on a second level, deliberate denial of information to the victim’s family and friends vis-à-vis said victim’s arrest or detention. This is what makes the act of enforced disappearance an inherently cruel and complex crime, requiring development of innovative standards of protection.

In 1941, Adolf Hitler issued the Night and Fog Decree (Nacht und Nebel Erlass), the purpose of which was to take persons from Nazi occupied territories who were “endangering German security” and make them disappear. The clear objective of the program was to terrorize and paralyze not just the victim’s family but society at large. Other countries followed suit: in the mid-1960s to the 1970s, enforced disappearances were used “as a tool of political repression” by security forces in Guatemala and Brazil (Sourav, 2015).

This practice began occurring on a massive scale across Chile, El Salvador, Peru, Columbia, Uruguay, Honduras, Sri Lanka, the Philippines, Uganda and Argentina. In Latin America, the bodies of the victims of enforced disappearances were either hidden or destroyed so as to conceal any material evidence of the crime, thus ensuring impunity for offenders. A chilling statement by General Iberico Saint Jean, the governor of Beunos Aires at the time of the first junta in Argentina merits mention here: “first we kill the subversives; then we kill collaborators; then… their sympathizers; then those who remain indifferent; and finally we kill the timid”.

Understanding the nature of enforced disappearances is crucial to combating impunity for the practice. This understanding began surfacing in the jurisprudence of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) and has now even been incorporated into the jurisprudence of Pakistani courts. The Velasquez Rodriguez v. Honduras case is a must-read case in understanding why the crime of enforced disappearance requires a different standard of proof than other criminal acts.

Briefly, the facts of the case were that Manfredo Velasquez Rodriguez, a Honduran national, had been kept in a detention center in Tegucigalpa since 12 September 1981, following which there was no information pertaining to his whereabouts. He left behind a wife and four young children. The IACtHR adopted a two-step approach to overcome the burden of proof obstacle, recognizing how victims face immense difficulties in collecting evidence in these cases. The two criteria, thus, required to be fulfilled by a claimant to prove a person’s disappearance are: first, that the claimant must demonstrate the existence of a governmental practice of enforced disappearances; and second, that the claimant must illustrate that the disappearance of the particular individual in question was linked to said practice.

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has also adopted a similar approach towards burden of proof requirements in cases of enforced disappearances, recognizing State denial of relevant facts in cases of this nature. There are similar judgments handed down by the Supreme Court of Pakistan (Mohabbat Shah case) and the Islamabad High Court (Mahera Sajid case and Muhammad Sharif Chaudhari case).

Despite evolving precedent on the matter, it appears that those responsible for perpetrating this heinous crime still rely on the prevailing culture of impunity, as illustrated most recently in the brazen abduction of journalist Matiullah Jan, who is the first to speak out after being disappeared in Pakistan.

Utilizing the golden standard for burden of proof in such cases, two things become crystal clear. First, that there is a pattern of disappearances prevalent in Pakistan, with victims of disappearances largely including social media activists, journalists, human rights defenders, bloggers, students and other critics of the military establishment in Pakistan. According to the Voice of Baloch Missing Persons, around 18,000 people have gone “missing” from Balochistan since 2001. Moreover, the Pakistan Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances has reported at least 1200 cases of alleged disappearances since 31 July 2017.

In flagrant disregard of the seriousness of this crime, the State of Pakistan, till date, has neither criminalized enforced disappearances (despite the Ministry of Human Rights proposing legislation in this regard) or brought to justice a single perpetrator of this crime. In the landmark Mahera Sajid judgment, the Honourable Chief Justice of the Islamabad High Court made some very pertinent observations. Page 24 of the judgment reads: “the positive Constitutional obligation of a State to protect fundamental rights and to prevent, investigate and punish any perpetrator in accordance with law is not only severely breached but simultaneously gives rise to an unimaginable paradox when the State and its functionaries assume the role of abductors”.

Another reason this judgment is critical precedent is because it cross-references jurisprudence of the ECtHR and the IACtHR, which is critical in ensuring cohesive interpretation of such acts between different regions. This is, in effect, one of the strongest ways to combat impunity, i.e. by bridging the gap between different legal systems and providing the necessary impetus to counter the fragmentation of international law.

To inflict this treatment on Pakistan citizens, without any consequences for the real perpetrators behind these acts, is an insult to the Constitution and the social contract. Fear and tyranny cannot last forever and even today, despite threats to their own security, journalists, civil society activists, lawyers and several others have banded together to demand an end to this culture of impunity. This systematic dehumanizing of Pakistani citizens must come to an end.

The seriousness of the crime can be seen in its “doubly paralyzing form of suffering” (Kirsten Anderson, 2006). On a first level, through removal of the victim from the protection of the law and on a second level, deliberate denial of information to the victim’s family and friends vis-à-vis said victim’s arrest or detention. This is what makes the act of enforced disappearance an inherently cruel and complex crime, requiring development of innovative standards of protection.

In 1941, Adolf Hitler issued the Night and Fog Decree (Nacht und Nebel Erlass), the purpose of which was to take persons from Nazi occupied territories who were “endangering German security” and make them disappear. The clear objective of the program was to terrorize and paralyze not just the victim’s family but society at large. Other countries followed suit: in the mid-1960s to the 1970s, enforced disappearances were used “as a tool of political repression” by security forces in Guatemala and Brazil (Sourav, 2015).

This practice began occurring on a massive scale across Chile, El Salvador, Peru, Columbia, Uruguay, Honduras, Sri Lanka, the Philippines, Uganda and Argentina. In Latin America, the bodies of the victims of enforced disappearances were either hidden or destroyed so as to conceal any material evidence of the crime, thus ensuring impunity for offenders. A chilling statement by General Iberico Saint Jean, the governor of Beunos Aires at the time of the first junta in Argentina merits mention here: “first we kill the subversives; then we kill collaborators; then… their sympathizers; then those who remain indifferent; and finally we kill the timid”.

Understanding the nature of enforced disappearances is crucial to combating impunity for the practice. This understanding began surfacing in the jurisprudence of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) and has now even been incorporated into the jurisprudence of Pakistani courts. The Velasquez Rodriguez v. Honduras case is a must-read case in understanding why the crime of enforced disappearance requires a different standard of proof than other criminal acts.

Briefly, the facts of the case were that Manfredo Velasquez Rodriguez, a Honduran national, had been kept in a detention center in Tegucigalpa since 12 September 1981, following which there was no information pertaining to his whereabouts. He left behind a wife and four young children. The IACtHR adopted a two-step approach to overcome the burden of proof obstacle, recognizing how victims face immense difficulties in collecting evidence in these cases. The two criteria, thus, required to be fulfilled by a claimant to prove a person’s disappearance are: first, that the claimant must demonstrate the existence of a governmental practice of enforced disappearances; and second, that the claimant must illustrate that the disappearance of the particular individual in question was linked to said practice.

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has also adopted a similar approach towards burden of proof requirements in cases of enforced disappearances, recognizing State denial of relevant facts in cases of this nature. There are similar judgments handed down by the Supreme Court of Pakistan (Mohabbat Shah case) and the Islamabad High Court (Mahera Sajid case and Muhammad Sharif Chaudhari case).

Despite evolving precedent on the matter, it appears that those responsible for perpetrating this heinous crime still rely on the prevailing culture of impunity, as illustrated most recently in the brazen abduction of journalist Matiullah Jan, who is the first to speak out after being disappeared in Pakistan.

Utilizing the golden standard for burden of proof in such cases, two things become crystal clear. First, that there is a pattern of disappearances prevalent in Pakistan, with victims of disappearances largely including social media activists, journalists, human rights defenders, bloggers, students and other critics of the military establishment in Pakistan. According to the Voice of Baloch Missing Persons, around 18,000 people have gone “missing” from Balochistan since 2001. Moreover, the Pakistan Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances has reported at least 1200 cases of alleged disappearances since 31 July 2017.

In flagrant disregard of the seriousness of this crime, the State of Pakistan, till date, has neither criminalized enforced disappearances (despite the Ministry of Human Rights proposing legislation in this regard) or brought to justice a single perpetrator of this crime. In the landmark Mahera Sajid judgment, the Honourable Chief Justice of the Islamabad High Court made some very pertinent observations. Page 24 of the judgment reads: “the positive Constitutional obligation of a State to protect fundamental rights and to prevent, investigate and punish any perpetrator in accordance with law is not only severely breached but simultaneously gives rise to an unimaginable paradox when the State and its functionaries assume the role of abductors”.

Another reason this judgment is critical precedent is because it cross-references jurisprudence of the ECtHR and the IACtHR, which is critical in ensuring cohesive interpretation of such acts between different regions. This is, in effect, one of the strongest ways to combat impunity, i.e. by bridging the gap between different legal systems and providing the necessary impetus to counter the fragmentation of international law.

To inflict this treatment on Pakistan citizens, without any consequences for the real perpetrators behind these acts, is an insult to the Constitution and the social contract. Fear and tyranny cannot last forever and even today, despite threats to their own security, journalists, civil society activists, lawyers and several others have banded together to demand an end to this culture of impunity. This systematic dehumanizing of Pakistani citizens must come to an end.