By Nadeem F. Paracha

In 1975-76, the American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) formed a special committee of ‘anti-communist experts.’ This was done after the Richard Nixon administration was severely criticized at a 1974 conference organized by a group of influential ‘nuclear strategists’ who bemoaned that President Nixon, his Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, and the Pentagon had ‘seriously underestimated the Soviet weapons program.’

French historian, Justin Visse in his book, Neo-conservatism: Biography of a Movement wrote that the conference ‘opened a new front against Nixon and Kissinger’s détente’ – a policy initiative which attempted to greatly scale back US-Soviet Cold War hostilities and (consequently) trigger cuts in the country’s military spending.

Nixon resigned from the presidency after being impeached for an internal espionage scandal against his opponents in the Democratic Party. According to Justin Visse, the then director of the CIA, George H. Bush, under the new President, Gerald Ford and - from January 1977 onwards - President Jimmy Carter, created a ‘Team B’ within the CIA made up of the hawkish critics of detente.

In December 1976, Team B’s first report suggested that the Soviet’s military spending and build-up was as rapid as that of the Nazis in Germany in the 1930s. The report also mentioned that the ‘primary goal of the Soviets was global supremacy.’

Team B’s reports, suggestions and estimates in this context were adopted by the administration of Jimmy Carter, but especially during the Presidency of Ronald Reagan (1980-88). This produced a more hostile attitude towards the Soviet Union, an increase in US military spending and the withering away of the policy of détente initiated by Nixon in 1972.

The invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979 by Soviet forces also strengthened Team B’s arguments. But the American society as a whole - which was still reeling from America’s human and material losses in the Vietnam conflict (1955-75) - was still wary of any large scale conflict involving the Americans.

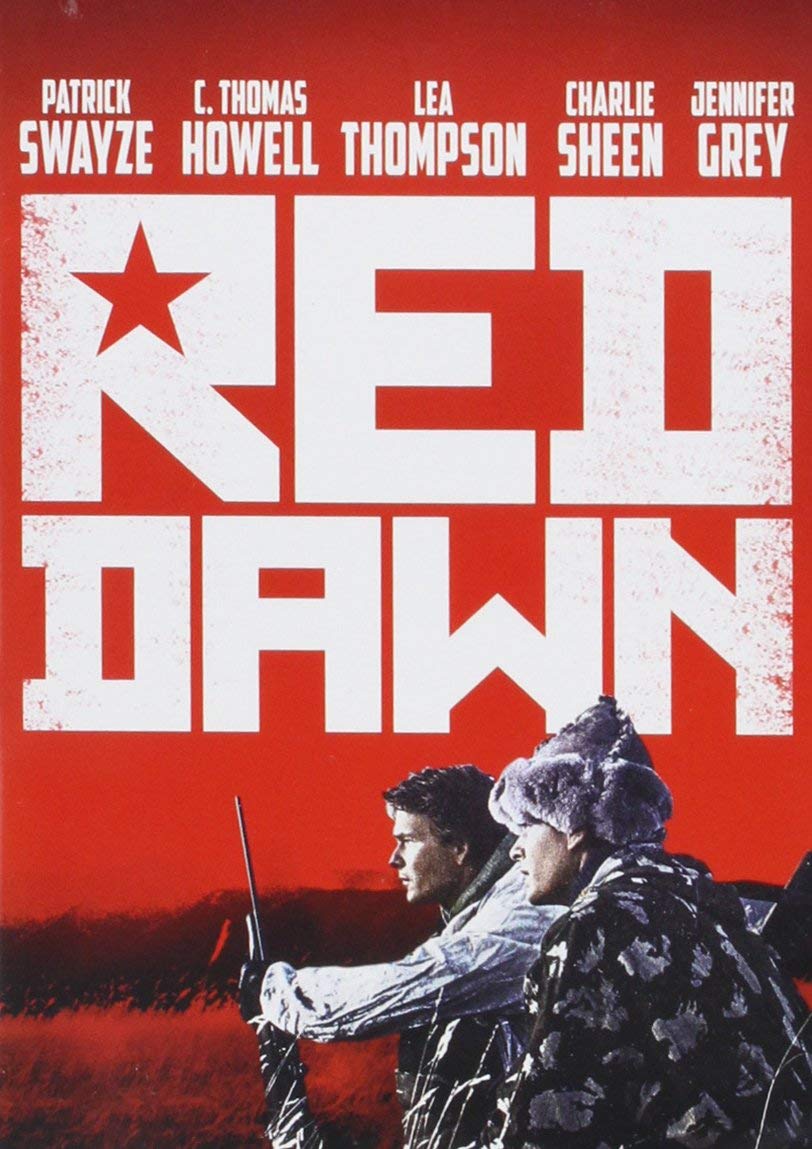

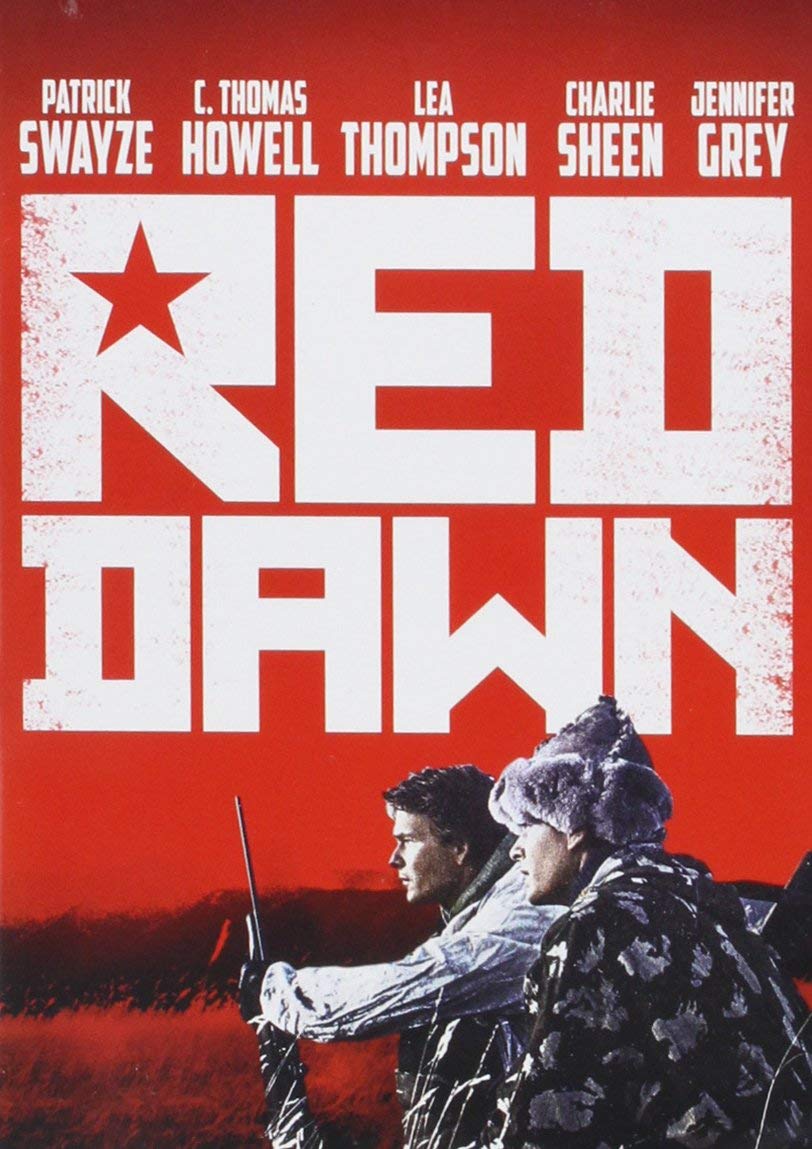

The United States has always been an active film producing and watching country. When Team B’s narrative of an expanding Soviet empire and military prowess firmly took root during Reagan’s administration, a Hollywood blockbuster, Red Dawn, appeared in American cinemas.

Helmed by award-winning screenwriter and director, John Millius, the film shows Soviet paratroopers secretly landing on American soil after the Soviet Union facilitates a communist coup in Mexico. Soviet soldiers (along with their allies, the Cubans) sabotage strategically important US military command posts until they are taken head-on by groups of common Americans (mentored by US military men) to repulse the Soviet attack. Though panned by critics for being nothing but a violent fantasy, the film was an immediate commercial hit, followed by a surge in anti-Soviet sentiment in the United States.

Acclaimed author, David Sirota, in a March 2011 piece for Salon wrote that the release of Red Dawn marked the beginnings of America’s ‘military-entertainment complex.’ The interesting bit is that (on a social level) the Red Dawn seemed to have had managed to get across Team B’s narrative in a populist manner, but in the year it was released (1984), Visse informs that CIA’s Deputy Director, Robert Gates, acknowledged that the CIA and its Team B had grossly overestimated Soviet military budget and production of weapons.

Renowned British documentary filmmaker Andrew Curtis in his 2004 documentary, The Power of Nightmares (BBC) suggested that Team B was well aware of the fact that it was inflating Soviet military might and intentions. The team’s goal was to neutralize Nixon and Kissinger’s policy of détente and break the United States’ ‘defeatist disposition’ (that it had adopted due to its failures in Vietnam). They did this by exaggerating the military capability of the Soviet Union and heighten the threat posed to the US by the Soviet Union.

So, due to the despondency triggered by America’s defeat in Vietnam, Team B’s narrative was readily adopted by the three post-Nixon administrations (Ford, Carter and especially, Reagan). And even when the CIA finally admitted that the narrative was highly exaggerated, films such as Red Dawn had managed to engrain the narrative in the American people’s minds.

The Soviets, of course, did not have an answer. Nobody watched their films. As a matter of fact, my research did not come up with any film made in the Soviet Union which countered the narrative proliferated by American films such as Red Dawn.

After Red Dawn came another film from Hollywood’s ‘military-entertainment complex’, called Invasion USA (1985), starring the famous Martial Arts action hero, Chuck Norris. Its plot was similar. Soviet and Cuban agents perform acts of terror on American soil as a prelude to a full blown Soviet invasion. Then there was also Sylvester Stallone’s Rambo (1985) which actually showed the US beating the hell out of the Soviets in Vietnam (a full decade after the United States lost a war there against the Soviet-backed Vietcong).

JM Valamitin 2005 book, Hollywood, Pentagon and the Washington, suggests that Hollywood’s ‘military-entertainment complex’ is still active. He wrote that key figures in the US film industry continue to have a well-established relationship with US military personnel and politicians. He adds that this interdependent partnership (‘by the power and suggestion of cinema’) causes ‘a surge in the nation’s collective consciousness of fundamental themes running through the current issues in the American strategic debate.’

But Valamitin also maintains that the aforementioned partnership was struck long before the 1980s. He informs that films produced by the Hollywood-Pentagon partnership haven’t always been blatant displays of American policies and political/ideological narrative as epitomized by blockbusters such as Red Dawn or Rambo.

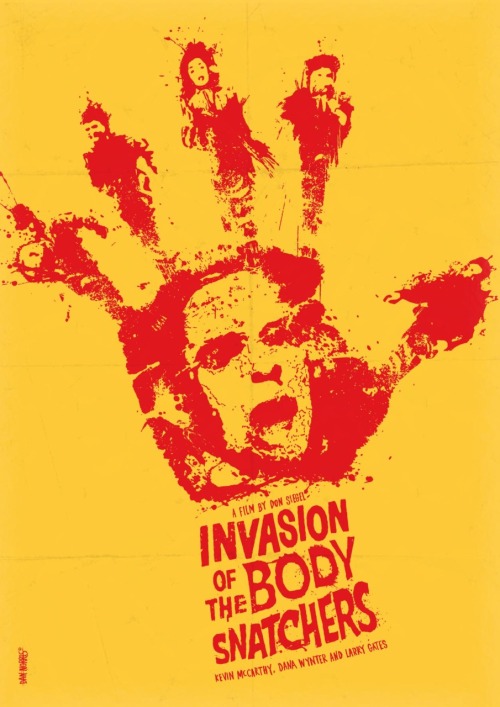

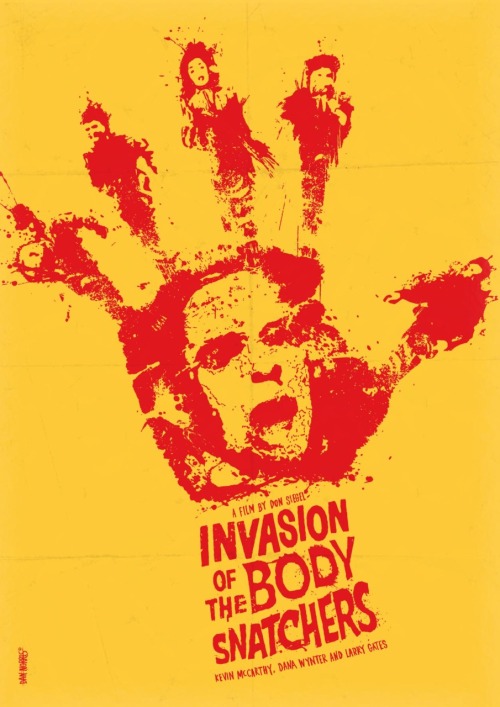

He gives the example of 1956’s The Invasion of the Body Snatchers. It is not a political or military action thriller. It’s a science fiction flick about aliens from another planet secretly taking over the world by disguising themselves as human beings. Valamitin explains the activities of the secretive aliens (blending in with common Americans to take over their minds) as a metaphor for Soviet infiltration (through communist agents). Valamitin wrote that the mentioned partnership has continued to produce films which directly as well as indirectly express American military and security policies.

The cinematic villains (threatening such policies) keep changing though. As Valamitin notes, from the beginning of the Cold War (in 1949) till the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, most Hollywood (political/ideological) villains were communists (mostly Soviet but also sometimes Chinese, East European and Cuban). By the early 1980s the radical Arab/Iranian as the bad guy had also been added to the list of Hollywood action villains.

Due to the worsening relationship between Washington and Tehran after the 1979 ‘Islamic Revolution’ in Iran, the Iranian villain in Hollywood was a reflection of the Iranian regime’s fanatical anti-Americanism. But, on the other hand, till the collapse of the Soviet Union, the radical Arab villain in Hollywood films was largely the Soviet-backed and secular Muslim ‘terrorist’, mostly Middle Eastern. 1977’s Black Sunday was the first blockbuster to exhibit exactly such a group of villains.

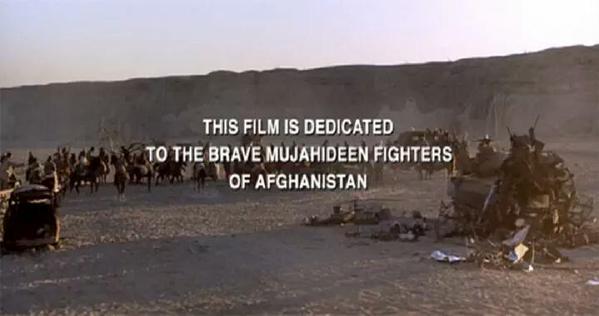

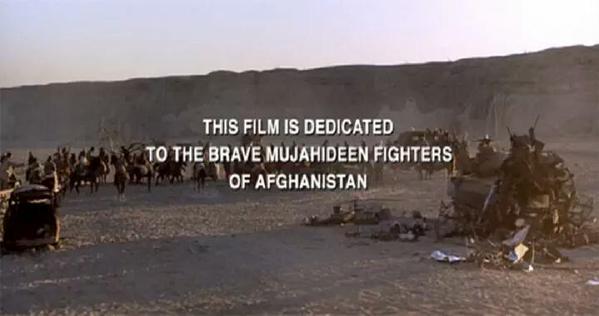

In 1986’s Delta Force, the villains in this context are anti-Israel Arab Muslim radicals who are ‘leftist’ in orientation (and thus being funded by the Soviet Union); whereas in the same year’s Under Siege the bad guys are Arabs being backed by the radical Islamic regime in Iran. Interestingly though, in 1988’s Rambo: III, the so-called ‘fundamentalist’/’Islamist’ guerilla fighters in Afghanistan are good guys because by then the US had already invested billions of dollars in funding the Afghan jihadists (against the Soviet forces).

The scenario however began to change after the following events: the collapse of the Soviet Union; the end of American involvement in Afghanistan; and the start of US involvement in Iraq. In 1994’s True Lies (starring popular action hero, Arnold Schwarzenegger) the villains become Arab jihadists.

In 1996’s Executive Decision the villains are again Arab jihadists. By the late 1990s, the American public had become conscious of the blow-back of American policies in Afghanistan (in the 1980s). This was immediately communicated by 1998’s The Siege in which Muslim men radicalized in Afghanistan commit terrorist attacks in the US.

So, as the situation in Afghanistan changed and the Soviet Union collapsed, so did America’s enemies, and thus, Hollywood villains. Especially after the tragic 9/11 event in New York. The communist bad guys vanished; and the leftist/secular Arab radical morphed into becoming religious Arab/Iranian/Afghan/Pakistani militant/terrorist.

Between 2001 and 2017, dozens of films and TV shows are centered on such villains. Despite the panning a lot of films (or TV shows) produced by the ‘military-entertainment complex’ have received by the more discerning critics, these films have played a most effective role in proliferating Washington’s internal and external policies and narratives - not only among audiences within the US but also around the world where Hollywood films remain equally popular.

The partnership between Pentagon and Hollywood has perfected this tactic, using it for decades now, and today it has become a vital tool of what became known as ‘Fourth Generation Warfare’. One of the aspects of this warfare includes ‘psychological warfare’ in which various modern modes of communication and media are used to inflict psychological inferences against opposing states.

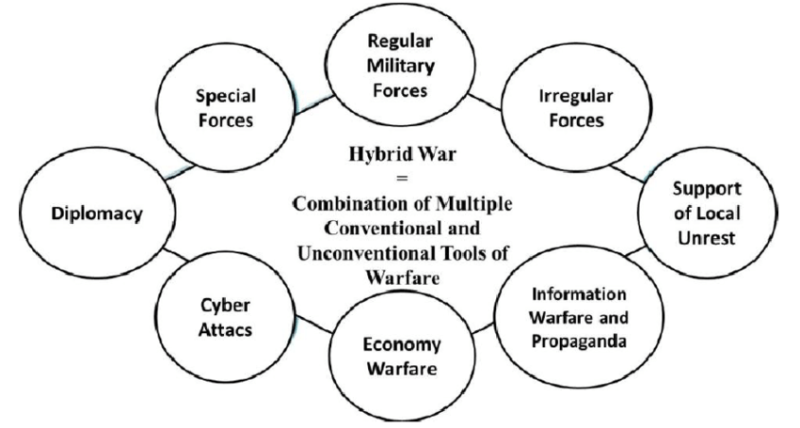

The medium of popular films are a major part of this kind of warfare, and also of what is now being described as ‘Fifth Generation Warfare’ that includes ‘Hybrid Warfare’ which is a blend of conventional, unconventional, information and cyber warfare.

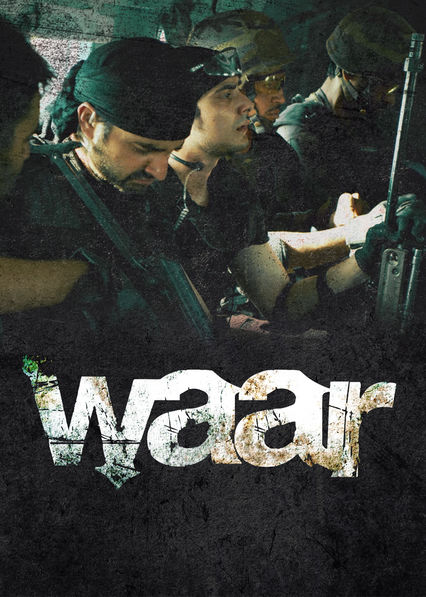

In 2013 when ISPR, the media arm of Pakistan’s army, funded the making of Urdu film Waar (strike), it wasn’t doing anything which the American ‘military-entertainment complex’ hasn’t been doing for decades. At the time, the Pakistan military had gone to war with a dangerous and destructive internal enemy i.e. the fanatical Islamic militants some of who were said to being bankrolled by the country’s external opponents.

Ad hoc security policies, an outdated state narrative (built during the 1980s’ anti-Soviet Afghan insurgency); and a populist hyper electronic media had created a muddled scenario in which most Pakistanis could not comprehend how elements (supposedly) demanding Shariah laws (even through violence) could be considered as anti-Pakistan or anti-Islam.

Waar (which became a major hit) tried to clear the confusion and at the same time communicate the state’s changing narrative about a vicious, fanatical internal enemy being backed by a cynical external foe (India).

But using film (or TV) for the purpose of advancing state policy is something entirely new in Pakistan. India picked up the tactic from the 1990s onward. Before the 1990s, however, this ploy was missing in both Indian and Pakistan. If one studies Pakistani and Indian films released between the 1950s and the 1980s, they will see that the plots of the films in both the countries were largely focused on domestic or internal social issues and not concerned at all with the issues pertaining to their respective countries’ internal and external politics.

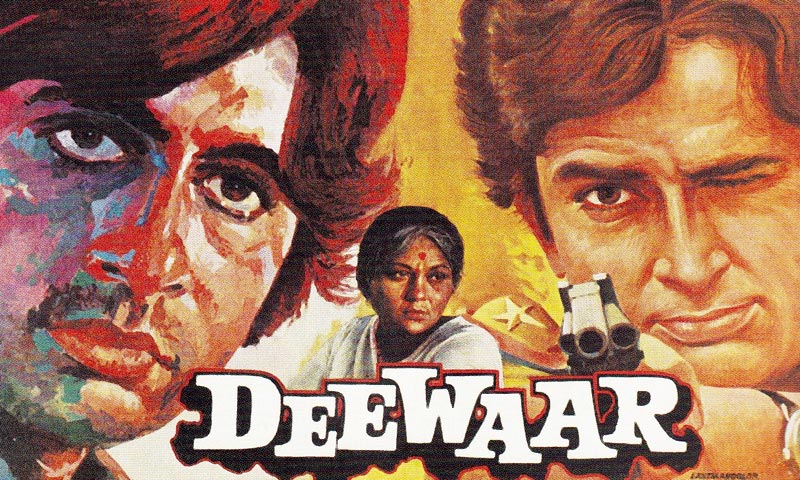

However, in the mid-1970s, Bollywood did manage to produce some powerful (but metaphorical) mediations on the crisis of the state and government which India faced between 1973 and 1979. This was done through films such as Deewar (1975) and Trishul (1979).

Deewar was released during a period when former Indian Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, had imposed an emergency to save her government that was being besieged by corruption and violent protests. Indian film critic, Nikhat Kazmi, in her 1997 book, Ire in the Soul, wrote that on the surface, Deewar was a well-scripted, emotional melodrama. However, Kazmi explained the character of the battered and violated mother in the film as a metaphorical representation of the besieged Indian state and government, violated by anti-state forces.

The mother’s two sons, one an angry young man (Amitabh Bachchan) and the other a police officer (Shashi Kapoor) handle their existentialist predicaments of being sons of a damaged mother in their own manner. In the end, even when the mother understands the anger of her elder son, she eventually sides with the other son (the policeman) in bringing down his renegade brother.

Kazmi states that the message was that a battered state and its institutions are the result of selfish motives of a few bad apples in the society and polity. No wonder, the film was allowed to screen even during the height of Indira’s emergency.

Years later, the success of Deewar and Trishul with their underlying pro-state political messages encouraged some Indian producers to stretch the tactic and extend it to incorporate India’s external enemies.

Nothing of the sort happened in Pakistan. But the fact is, even if any Pakistani filmmaker or the state had wanted to do so, the resultant product would not have been effective due to the reactionary cultural policies of the Zia-ul-Haq regime in the 1980s, the Pakistan film industry had all but collapsed.

So Pakistan had no answer when Bollywood released one of the first Indian films to portray a villain with connections to Pakistan. The film was 1996’s Dilljale in which the main villain is a sinister Indian who is on the payroll of Pakistan’s ISI. The subtlety of the metaphorical political/propaganda films such as Invasion of the Body Snatchers and Deewar is clearly missing. But Bollywood’s onslaught against the Pakistani state had taken off.

India’s film industry is mammoth. It finances itself with the huge profits that it makes from its many releases. It is not dependent on direct financing from state institutions. But many investors associated with the process of bankrolling films in India have relations with influential politicians and members of India’s state institutions. These investors have a lot of say in the formulation of plots and stories of the films that they finance.

Secondly, Bollywood filmmakers quickly pick up on issues proliferated by fiery Indian politicians, media and ideologues and weave these issues into their films’ plots. For example, during the initial stages of campaigning for the 1999 elections in India, most contestants began to highlight the deteriorating relations between India and Pakistan by using overt anti-Pakistan language.

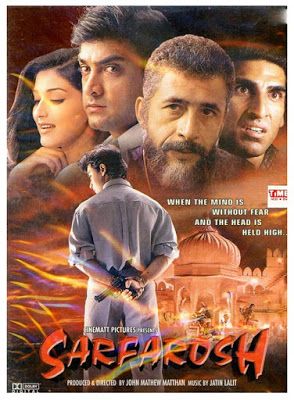

Consequently, Indian filmmaker and producer JM Matthan released Sarfarosh. Starring the charismatic Aamir Khan as the patriotic all-Indian hero, the film’s villain was played by Naseeruddin Shah in the shape of a sinister criminal who is, of course, on the payroll of the Pakistani intelligence agencies.

Numerous such films have been rolled out by Bollywood after the commercial success of Sarfarosh. During the rise of neo-Hindu nationalism in India, the tones and tenors of these films have become rather blatant, sometimes to the point of becoming unintentional self-parodies.

These films lack the finesse of Hollywood propaganda films, nor are they in anyway metaphorical or subtle. Some critics may see them as vessels for collective venting-out rituals for the Indian masses conditioned by their politicians, state and media to accept particular nationalist and anti-Pakistan narratives. Something like an extended version of the concept of the ‘Two Minutes of Hate’ popularized by George Orwell in his novel 1984. Yet, these films do fit well in the barrel of India’s version of Fourth and Fifth Generation Warfare, mainly because Bollywood has truly gone global.

There are those who may argue that art should be kept aloof from what goes on between conflicting states. But with the mushrooming and increasing reach of digital/cyber technologies and the universal expansion of entertainment industries, nations facing internal or external conflicts cannot ignore the idea of using modern popular art-forms (such as film and TV) to put forth their narratives in an increasingly chaotic and complex marketplace of various narratives of competing states.

For the past decade or so, Pakistan has been involved in Fourth and now Fifth Generation Warfare on many fronts. There is the physical, ideological and psychological war against internal (but ‘externally-backed’) Islamic militant outfits, and Baloch separatists; there is the semi-physical, psychological and information war against India; and there is also tension between a state (wanting to reform and redefine the rationale of Pakistani nationhood) and that part of the polity which was radicalized by the more belligerent, obscurantist (and outdated) nationalist narrative honed in the 1980s. The Pakistani entertainment industries seem cut-off from these realities.

Indeed, patriotic songs still continue to be recorded and citizens and politicians continue to give lip-service to the whole idea of patriotism. But the idea in this context being used by entertainers, politicians and TV personalities is entirely rhetorical in essence, devoid of the current (and complex) realities of hybrid warfare, and thus, are outdated and ineffectual.

ISPR has tried thrice to use the recent revival of Pakistani cinema to counter Bollywood’s onslaught and internal extremist propaganda, by giving a more contemporary shape (in the context of hybrid warfare) to new Pakistani films.

The experiment began with 2007’s Khuda Kay Leeay. Directed by Shoaib Mansoor, the film prudently tackled the phenomenon of the spread of extremism in the Pakistani society by suggesting that the original disposition of the Pakistani nation and nationalism was inherently moderate. The experiment was carried forward with Waar (which we have already discussed) and then Yalgaar (apart from some TV plays) which tackled internal extremist thought and the Indian influence in exploiting this thought (and action) to destabilize Pakistan.

But unlike in India, no Pakistani filmmaker has willed to come up with a product on his or her own which expresses the Pakistani state’s new, evolving narrative. Maybe the state (and government) itself have not been able to communicate it in a more effective manner for anyone to use his or her artistic prowess to put out this narrative to counter those narratives demonizing Pakistan as a ‘pariah state’.

Or the state has perhaps picked those show-biz or political personalities who have either lost their sheen; or simply don’t have the tact to intelligently weave the narrative into their product; or they often end up merging the new narrative with the outdated one, thus causing more confusion (and even repulsion).

In 1975-76, the American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) formed a special committee of ‘anti-communist experts.’ This was done after the Richard Nixon administration was severely criticized at a 1974 conference organized by a group of influential ‘nuclear strategists’ who bemoaned that President Nixon, his Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, and the Pentagon had ‘seriously underestimated the Soviet weapons program.’

French historian, Justin Visse in his book, Neo-conservatism: Biography of a Movement wrote that the conference ‘opened a new front against Nixon and Kissinger’s détente’ – a policy initiative which attempted to greatly scale back US-Soviet Cold War hostilities and (consequently) trigger cuts in the country’s military spending.

Nixon resigned from the presidency after being impeached for an internal espionage scandal against his opponents in the Democratic Party. According to Justin Visse, the then director of the CIA, George H. Bush, under the new President, Gerald Ford and - from January 1977 onwards - President Jimmy Carter, created a ‘Team B’ within the CIA made up of the hawkish critics of detente.

In December 1976, Team B’s first report suggested that the Soviet’s military spending and build-up was as rapid as that of the Nazis in Germany in the 1930s. The report also mentioned that the ‘primary goal of the Soviets was global supremacy.’

Team B’s reports, suggestions and estimates in this context were adopted by the administration of Jimmy Carter, but especially during the Presidency of Ronald Reagan (1980-88). This produced a more hostile attitude towards the Soviet Union, an increase in US military spending and the withering away of the policy of détente initiated by Nixon in 1972.

The invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979 by Soviet forces also strengthened Team B’s arguments. But the American society as a whole - which was still reeling from America’s human and material losses in the Vietnam conflict (1955-75) - was still wary of any large scale conflict involving the Americans.

The United States has always been an active film producing and watching country. When Team B’s narrative of an expanding Soviet empire and military prowess firmly took root during Reagan’s administration, a Hollywood blockbuster, Red Dawn, appeared in American cinemas.

Helmed by award-winning screenwriter and director, John Millius, the film shows Soviet paratroopers secretly landing on American soil after the Soviet Union facilitates a communist coup in Mexico. Soviet soldiers (along with their allies, the Cubans) sabotage strategically important US military command posts until they are taken head-on by groups of common Americans (mentored by US military men) to repulse the Soviet attack. Though panned by critics for being nothing but a violent fantasy, the film was an immediate commercial hit, followed by a surge in anti-Soviet sentiment in the United States.

Acclaimed author, David Sirota, in a March 2011 piece for Salon wrote that the release of Red Dawn marked the beginnings of America’s ‘military-entertainment complex.’ The interesting bit is that (on a social level) the Red Dawn seemed to have had managed to get across Team B’s narrative in a populist manner, but in the year it was released (1984), Visse informs that CIA’s Deputy Director, Robert Gates, acknowledged that the CIA and its Team B had grossly overestimated Soviet military budget and production of weapons.

Renowned British documentary filmmaker Andrew Curtis in his 2004 documentary, The Power of Nightmares (BBC) suggested that Team B was well aware of the fact that it was inflating Soviet military might and intentions. The team’s goal was to neutralize Nixon and Kissinger’s policy of détente and break the United States’ ‘defeatist disposition’ (that it had adopted due to its failures in Vietnam). They did this by exaggerating the military capability of the Soviet Union and heighten the threat posed to the US by the Soviet Union.

So, due to the despondency triggered by America’s defeat in Vietnam, Team B’s narrative was readily adopted by the three post-Nixon administrations (Ford, Carter and especially, Reagan). And even when the CIA finally admitted that the narrative was highly exaggerated, films such as Red Dawn had managed to engrain the narrative in the American people’s minds.

1984’s Red Dawn: One of the first major hits produced by Hollywood’s so-called military-entertainment-complex.

The Soviets, of course, did not have an answer. Nobody watched their films. As a matter of fact, my research did not come up with any film made in the Soviet Union which countered the narrative proliferated by American films such as Red Dawn.

After Red Dawn came another film from Hollywood’s ‘military-entertainment complex’, called Invasion USA (1985), starring the famous Martial Arts action hero, Chuck Norris. Its plot was similar. Soviet and Cuban agents perform acts of terror on American soil as a prelude to a full blown Soviet invasion. Then there was also Sylvester Stallone’s Rambo (1985) which actually showed the US beating the hell out of the Soviets in Vietnam (a full decade after the United States lost a war there against the Soviet-backed Vietcong).

JM Valamitin 2005 book, Hollywood, Pentagon and the Washington, suggests that Hollywood’s ‘military-entertainment complex’ is still active. He wrote that key figures in the US film industry continue to have a well-established relationship with US military personnel and politicians. He adds that this interdependent partnership (‘by the power and suggestion of cinema’) causes ‘a surge in the nation’s collective consciousness of fundamental themes running through the current issues in the American strategic debate.’

But Valamitin also maintains that the aforementioned partnership was struck long before the 1980s. He informs that films produced by the Hollywood-Pentagon partnership haven’t always been blatant displays of American policies and political/ideological narrative as epitomized by blockbusters such as Red Dawn or Rambo.

He gives the example of 1956’s The Invasion of the Body Snatchers. It is not a political or military action thriller. It’s a science fiction flick about aliens from another planet secretly taking over the world by disguising themselves as human beings. Valamitin explains the activities of the secretive aliens (blending in with common Americans to take over their minds) as a metaphor for Soviet infiltration (through communist agents). Valamitin wrote that the mentioned partnership has continued to produce films which directly as well as indirectly express American military and security policies.

1956’s Invasion of Body Snatchers used alien take-over plot formula as a metaphor for Soviet/communist infiltration of American society.

The cinematic villains (threatening such policies) keep changing though. As Valamitin notes, from the beginning of the Cold War (in 1949) till the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, most Hollywood (political/ideological) villains were communists (mostly Soviet but also sometimes Chinese, East European and Cuban). By the early 1980s the radical Arab/Iranian as the bad guy had also been added to the list of Hollywood action villains.

Due to the worsening relationship between Washington and Tehran after the 1979 ‘Islamic Revolution’ in Iran, the Iranian villain in Hollywood was a reflection of the Iranian regime’s fanatical anti-Americanism. But, on the other hand, till the collapse of the Soviet Union, the radical Arab villain in Hollywood films was largely the Soviet-backed and secular Muslim ‘terrorist’, mostly Middle Eastern. 1977’s Black Sunday was the first blockbuster to exhibit exactly such a group of villains.

In 1986’s Delta Force, the villains in this context are anti-Israel Arab Muslim radicals who are ‘leftist’ in orientation (and thus being funded by the Soviet Union); whereas in the same year’s Under Siege the bad guys are Arabs being backed by the radical Islamic regime in Iran. Interestingly though, in 1988’s Rambo: III, the so-called ‘fundamentalist’/’Islamist’ guerilla fighters in Afghanistan are good guys because by then the US had already invested billions of dollars in funding the Afghan jihadists (against the Soviet forces).

The scenario however began to change after the following events: the collapse of the Soviet Union; the end of American involvement in Afghanistan; and the start of US involvement in Iraq. In 1994’s True Lies (starring popular action hero, Arnold Schwarzenegger) the villains become Arab jihadists.

In 1996’s Executive Decision the villains are again Arab jihadists. By the late 1990s, the American public had become conscious of the blow-back of American policies in Afghanistan (in the 1980s). This was immediately communicated by 1998’s The Siege in which Muslim men radicalized in Afghanistan commit terrorist attacks in the US.

In 1977’s Black Sunday, one of the major villains is a leftist Palestinian radical.

In 1988’s Rambo 3, radical Afghan Islamists (the Mujahedeen) are heroes.

10 years later, in 1998’s The Siege, the once friendly Islamists became villains.

So, as the situation in Afghanistan changed and the Soviet Union collapsed, so did America’s enemies, and thus, Hollywood villains. Especially after the tragic 9/11 event in New York. The communist bad guys vanished; and the leftist/secular Arab radical morphed into becoming religious Arab/Iranian/Afghan/Pakistani militant/terrorist.

Between 2001 and 2017, dozens of films and TV shows are centered on such villains. Despite the panning a lot of films (or TV shows) produced by the ‘military-entertainment complex’ have received by the more discerning critics, these films have played a most effective role in proliferating Washington’s internal and external policies and narratives - not only among audiences within the US but also around the world where Hollywood films remain equally popular.

The partnership between Pentagon and Hollywood has perfected this tactic, using it for decades now, and today it has become a vital tool of what became known as ‘Fourth Generation Warfare’. One of the aspects of this warfare includes ‘psychological warfare’ in which various modern modes of communication and media are used to inflict psychological inferences against opposing states.

The medium of popular films are a major part of this kind of warfare, and also of what is now being described as ‘Fifth Generation Warfare’ that includes ‘Hybrid Warfare’ which is a blend of conventional, unconventional, information and cyber warfare.

In 2013 when ISPR, the media arm of Pakistan’s army, funded the making of Urdu film Waar (strike), it wasn’t doing anything which the American ‘military-entertainment complex’ hasn’t been doing for decades. At the time, the Pakistan military had gone to war with a dangerous and destructive internal enemy i.e. the fanatical Islamic militants some of who were said to being bankrolled by the country’s external opponents.

Ad hoc security policies, an outdated state narrative (built during the 1980s’ anti-Soviet Afghan insurgency); and a populist hyper electronic media had created a muddled scenario in which most Pakistanis could not comprehend how elements (supposedly) demanding Shariah laws (even through violence) could be considered as anti-Pakistan or anti-Islam.

Waar (which became a major hit) tried to clear the confusion and at the same time communicate the state’s changing narrative about a vicious, fanatical internal enemy being backed by a cynical external foe (India).

But using film (or TV) for the purpose of advancing state policy is something entirely new in Pakistan. India picked up the tactic from the 1990s onward. Before the 1990s, however, this ploy was missing in both Indian and Pakistan. If one studies Pakistani and Indian films released between the 1950s and the 1980s, they will see that the plots of the films in both the countries were largely focused on domestic or internal social issues and not concerned at all with the issues pertaining to their respective countries’ internal and external politics.

However, in the mid-1970s, Bollywood did manage to produce some powerful (but metaphorical) mediations on the crisis of the state and government which India faced between 1973 and 1979. This was done through films such as Deewar (1975) and Trishul (1979).

Deewar was released during a period when former Indian Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, had imposed an emergency to save her government that was being besieged by corruption and violent protests. Indian film critic, Nikhat Kazmi, in her 1997 book, Ire in the Soul, wrote that on the surface, Deewar was a well-scripted, emotional melodrama. However, Kazmi explained the character of the battered and violated mother in the film as a metaphorical representation of the besieged Indian state and government, violated by anti-state forces.

The mother’s two sons, one an angry young man (Amitabh Bachchan) and the other a police officer (Shashi Kapoor) handle their existentialist predicaments of being sons of a damaged mother in their own manner. In the end, even when the mother understands the anger of her elder son, she eventually sides with the other son (the policeman) in bringing down his renegade brother.

Kazmi states that the message was that a battered state and its institutions are the result of selfish motives of a few bad apples in the society and polity. No wonder, the film was allowed to screen even during the height of Indira’s emergency.

Years later, the success of Deewar and Trishul with their underlying pro-state political messages encouraged some Indian producers to stretch the tactic and extend it to incorporate India’s external enemies.

Nothing of the sort happened in Pakistan. But the fact is, even if any Pakistani filmmaker or the state had wanted to do so, the resultant product would not have been effective due to the reactionary cultural policies of the Zia-ul-Haq regime in the 1980s, the Pakistan film industry had all but collapsed.

So Pakistan had no answer when Bollywood released one of the first Indian films to portray a villain with connections to Pakistan. The film was 1996’s Dilljale in which the main villain is a sinister Indian who is on the payroll of Pakistan’s ISI. The subtlety of the metaphorical political/propaganda films such as Invasion of the Body Snatchers and Deewar is clearly missing. But Bollywood’s onslaught against the Pakistani state had taken off.

India’s film industry is mammoth. It finances itself with the huge profits that it makes from its many releases. It is not dependent on direct financing from state institutions. But many investors associated with the process of bankrolling films in India have relations with influential politicians and members of India’s state institutions. These investors have a lot of say in the formulation of plots and stories of the films that they finance.

Secondly, Bollywood filmmakers quickly pick up on issues proliferated by fiery Indian politicians, media and ideologues and weave these issues into their films’ plots. For example, during the initial stages of campaigning for the 1999 elections in India, most contestants began to highlight the deteriorating relations between India and Pakistan by using overt anti-Pakistan language.

Consequently, Indian filmmaker and producer JM Matthan released Sarfarosh. Starring the charismatic Aamir Khan as the patriotic all-Indian hero, the film’s villain was played by Naseeruddin Shah in the shape of a sinister criminal who is, of course, on the payroll of the Pakistani intelligence agencies.

Numerous such films have been rolled out by Bollywood after the commercial success of Sarfarosh. During the rise of neo-Hindu nationalism in India, the tones and tenors of these films have become rather blatant, sometimes to the point of becoming unintentional self-parodies.

These films lack the finesse of Hollywood propaganda films, nor are they in anyway metaphorical or subtle. Some critics may see them as vessels for collective venting-out rituals for the Indian masses conditioned by their politicians, state and media to accept particular nationalist and anti-Pakistan narratives. Something like an extended version of the concept of the ‘Two Minutes of Hate’ popularized by George Orwell in his novel 1984. Yet, these films do fit well in the barrel of India’s version of Fourth and Fifth Generation Warfare, mainly because Bollywood has truly gone global.

There are those who may argue that art should be kept aloof from what goes on between conflicting states. But with the mushrooming and increasing reach of digital/cyber technologies and the universal expansion of entertainment industries, nations facing internal or external conflicts cannot ignore the idea of using modern popular art-forms (such as film and TV) to put forth their narratives in an increasingly chaotic and complex marketplace of various narratives of competing states.

For the past decade or so, Pakistan has been involved in Fourth and now Fifth Generation Warfare on many fronts. There is the physical, ideological and psychological war against internal (but ‘externally-backed’) Islamic militant outfits, and Baloch separatists; there is the semi-physical, psychological and information war against India; and there is also tension between a state (wanting to reform and redefine the rationale of Pakistani nationhood) and that part of the polity which was radicalized by the more belligerent, obscurantist (and outdated) nationalist narrative honed in the 1980s. The Pakistani entertainment industries seem cut-off from these realities.

Indeed, patriotic songs still continue to be recorded and citizens and politicians continue to give lip-service to the whole idea of patriotism. But the idea in this context being used by entertainers, politicians and TV personalities is entirely rhetorical in essence, devoid of the current (and complex) realities of hybrid warfare, and thus, are outdated and ineffectual.

ISPR has tried thrice to use the recent revival of Pakistani cinema to counter Bollywood’s onslaught and internal extremist propaganda, by giving a more contemporary shape (in the context of hybrid warfare) to new Pakistani films.

The experiment began with 2007’s Khuda Kay Leeay. Directed by Shoaib Mansoor, the film prudently tackled the phenomenon of the spread of extremism in the Pakistani society by suggesting that the original disposition of the Pakistani nation and nationalism was inherently moderate. The experiment was carried forward with Waar (which we have already discussed) and then Yalgaar (apart from some TV plays) which tackled internal extremist thought and the Indian influence in exploiting this thought (and action) to destabilize Pakistan.

But unlike in India, no Pakistani filmmaker has willed to come up with a product on his or her own which expresses the Pakistani state’s new, evolving narrative. Maybe the state (and government) itself have not been able to communicate it in a more effective manner for anyone to use his or her artistic prowess to put out this narrative to counter those narratives demonizing Pakistan as a ‘pariah state’.

Or the state has perhaps picked those show-biz or political personalities who have either lost their sheen; or simply don’t have the tact to intelligently weave the narrative into their product; or they often end up merging the new narrative with the outdated one, thus causing more confusion (and even repulsion).