By Ali Abbas

Tax Revenue Generation in Pakistan

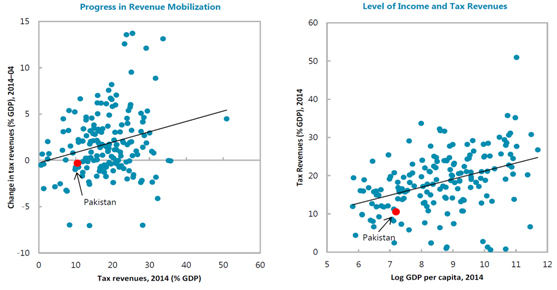

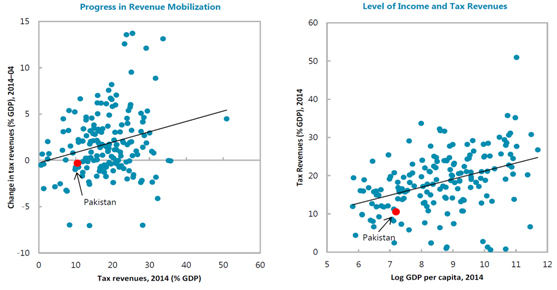

Pakistan has not been able to actualize its revenue-generation potential. Estimates put Pakistan’s tax capacity at 22% of GDP, but the country collected taxes worth approximately 12% of GDP in FY 2015-16. The graph below which is borrowed from Serhan Cevik’s IMF Working Paper published in 2016 shows that Pakistan is under-performing on the revenue as a percentage of GDP metric, as compared to other countries.

Further, while the state uses a number of instruments for collecting taxes, indirect taxes such as those paid on sales and manufacturing of goods and services have remained a more popular policy tool amongst policymakers, as compared to direct taxes such as income, corporate and wealth tax. Indirect taxes account for approximately 65% of federal tax revenue. Few of the key tax collection tools are federal excise duty, sales tax, customs duties, income tax, agriculture tax, property tax, GST on services and motor vehicle tax.

More recently, the tax-to-GDP ratio stood at 10.5% in FY 2016-17 – a drop in revenue-generation, making things worse for policymakers who are further constrained in providing public goods and services. While there has been growth in revenue collection during the first three quarters of FY 2017-18, this growth rate is less than what was projected by the government. Against the projected growth rate in tax collection of 19.2% which the government had targeted for a budget deficit of 4.1%, the FBR reported collection growth of 17.7%, which is expected to worsen the budget deficit.

Pakistan’s weak tax collection regime stems from poor enforcement and auditing mechanisms, low registration of workers on the income tax rolls, high rates of exemptions given to different stakeholders, and low tax morale in the country, where corruption is perceived to be rampant, and citizens find it hard to link their tax payments to provision of social sector services.

Innovative Tax Schemes

In an environment of weak revenue-generation, innovative tax-collection schemes can provide the government with fresh ideas about how to strengthen the tax regime. One such scheme was implemented in the property tax market in Punjab province, between 2011 and 2013.

A group of researchers from Harvard University, MIT, London School of Economics and the Center for Economic Research in Pakistan (CERP) implemented a series of experiments in the Punjab province, in collaboration with the Excise & Taxation (E&T) department Punjab. The objective of these experiments was to see how providing incentives to tax collectors would impact overall revenue-generation by the E&T department. Such incentives are common in the corporate sector, such as when salesmen are given a commission for increasing sales of a product.

While the project idea was simple, the collaboration between academic experts and on-the-ground tax officials was unique in the Pakistani context. Further, the size of the project was not small. Out of a total of 482 tax circles, 218 circles – including 550 tax personnel – were included in the experiment. Tax circles are not actually “circles”, but it’s a name that has stuck to them. These are just different local areas in which tax policy is enforced and taxes are collected by a team of tax officials, which includes the Excise & Taxation Officer (ETO), the Assistant Excise & Taxation Officer (AETO), the inspector, constable and clerk, by descending order of seniority.

Tax inspectors and supervisory staff including AETOs were given incentives in the form of cash for increased revenue-generation. These incentives were of different kinds. Staff were divided into three groups and given bonuses using the following strategies:

The project increased tax collection in circles where bonuses were given by a total of 12 percentage points, as compared to circles where this was not done. This is equal to an increase of Rs 240 million in revenue from the 218 circles in which the scheme was implemented over the two-year treatment period. The overall return on investment for the E&T department for this project was 22.1%, better than the ROI from investing in many other areas to generate income, such as stocks and treasury bonds. The team also found that the simplest form of bonuses, described in (1) above, performed the best.

5 reasons why this scheme improved tax collection

Collection was improved because of the following reasons:

Can it be replicated and continued?

As discussed earlier, the take-up of the project by the Punjab government and specifically, the Excise & Taxation department was critical to its success. Whether such an incentives scheme is sustainable is another matter altogether. The project’s technical details were devised by a group of academics at top academic institutions. These academics who were well-versed in the art of conducting such experiments, were assisted by a team of highly-skilled researchers in Lahore. Developing and retaining such human capital at government departments is not a simple task, given the differentials in incentives provided by academic and governmental organizations. Therefore, it is unlikely that the design of the project can be perpetuated by on-the-ground officials who have a different skill set and expertise. Further, for the duration of the project, it was protected from political and bureaucratic considerations, to the best of the ability of those at the top of the department. However, with the project moving solely into the domain of the department, without external assistance and accountability, it will be much harder for the E&T department to prevent incentives to be tailored in a way which “makes everyone happy”. This would appear to be the biggest challenge for using incentives to generate similar revenue gains.

However, if such challenges can be overcome, a financial incentives structure for tax collectors has tremendous potential to improve tax collection, not just in Punjab province, but in other regions as well. Counterparts to the E&T department in KPK, Sindh and Balochistan can exploit similar incentives, suited to the provincial context, to generate gains in revenue-collection. Such out-of-the-box mechanisms can contribute to correcting Pakistan’s revenue-generation trajectory, providing greater funds for investing into public goods such as health, education, water & sanitation, and infrastructure.

Tax Revenue Generation in Pakistan

Pakistan has not been able to actualize its revenue-generation potential. Estimates put Pakistan’s tax capacity at 22% of GDP, but the country collected taxes worth approximately 12% of GDP in FY 2015-16. The graph below which is borrowed from Serhan Cevik’s IMF Working Paper published in 2016 shows that Pakistan is under-performing on the revenue as a percentage of GDP metric, as compared to other countries.

Further, while the state uses a number of instruments for collecting taxes, indirect taxes such as those paid on sales and manufacturing of goods and services have remained a more popular policy tool amongst policymakers, as compared to direct taxes such as income, corporate and wealth tax. Indirect taxes account for approximately 65% of federal tax revenue. Few of the key tax collection tools are federal excise duty, sales tax, customs duties, income tax, agriculture tax, property tax, GST on services and motor vehicle tax.

Against the projected growth rate in tax collection of 19.2% which the government had targeted for a budget deficit of 4.1%, the FBR reported collection growth of 17.7%, which is expected to worsen the budget deficit.

More recently, the tax-to-GDP ratio stood at 10.5% in FY 2016-17 – a drop in revenue-generation, making things worse for policymakers who are further constrained in providing public goods and services. While there has been growth in revenue collection during the first three quarters of FY 2017-18, this growth rate is less than what was projected by the government. Against the projected growth rate in tax collection of 19.2% which the government had targeted for a budget deficit of 4.1%, the FBR reported collection growth of 17.7%, which is expected to worsen the budget deficit.

Pakistan’s weak tax collection regime stems from poor enforcement and auditing mechanisms, low registration of workers on the income tax rolls, high rates of exemptions given to different stakeholders, and low tax morale in the country, where corruption is perceived to be rampant, and citizens find it hard to link their tax payments to provision of social sector services.

Innovative Tax Schemes

In an environment of weak revenue-generation, innovative tax-collection schemes can provide the government with fresh ideas about how to strengthen the tax regime. One such scheme was implemented in the property tax market in Punjab province, between 2011 and 2013.

A group of researchers from Harvard University, MIT, London School of Economics and the Center for Economic Research in Pakistan (CERP) implemented a series of experiments in the Punjab province, in collaboration with the Excise & Taxation (E&T) department Punjab. The objective of these experiments was to see how providing incentives to tax collectors would impact overall revenue-generation by the E&T department. Such incentives are common in the corporate sector, such as when salesmen are given a commission for increasing sales of a product.

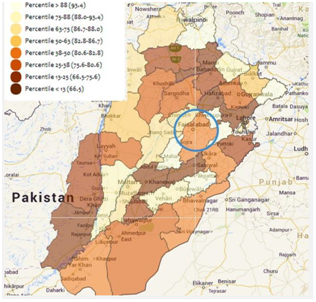

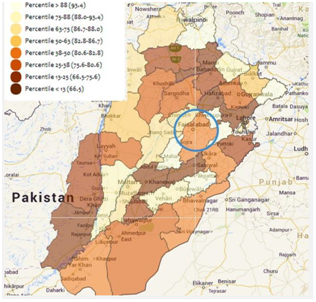

Source: Property tax experiment in Pakistan, Incentivizing tax collection and improving performance, 3ie, August 2016

While the project idea was simple, the collaboration between academic experts and on-the-ground tax officials was unique in the Pakistani context. Further, the size of the project was not small. Out of a total of 482 tax circles, 218 circles – including 550 tax personnel – were included in the experiment. Tax circles are not actually “circles”, but it’s a name that has stuck to them. These are just different local areas in which tax policy is enforced and taxes are collected by a team of tax officials, which includes the Excise & Taxation Officer (ETO), the Assistant Excise & Taxation Officer (AETO), the inspector, constable and clerk, by descending order of seniority.

The overall return on investment for the E&T department for this project was 22.1%, better than the ROI from investing in many other areas to generate income, such as stocks and treasury bonds.

Tax inspectors and supervisory staff including AETOs were given incentives in the form of cash for increased revenue-generation. These incentives were of different kinds. Staff were divided into three groups and given bonuses using the following strategies:

- Circle staff were given 20% to 40% of the increased value of taxes collected above a historical benchmark. These incentives were large, at times doubling the base salary of tax staff, and more.

- Same as above, but at the end of the year, staff members received a bonus if taxpayers were more satisfied with their performance and their accuracy of property tax assessment was good which increased their basic bonus, otherwise they had to pay a penalty which reduced the basic bonus.

- All experimental staff members received a basic bonus, but the E&T department’s Performance Evaluation Committee (PEC) used additional measures to increase or decrease this basic bonus.

The project increased tax collection in circles where bonuses were given by a total of 12 percentage points, as compared to circles where this was not done. This is equal to an increase of Rs 240 million in revenue from the 218 circles in which the scheme was implemented over the two-year treatment period. The overall return on investment for the E&T department for this project was 22.1%, better than the ROI from investing in many other areas to generate income, such as stocks and treasury bonds. The team also found that the simplest form of bonuses, described in (1) above, performed the best.

5 reasons why this scheme improved tax collection

Collection was improved because of the following reasons:

- The complete ownership of the project by the E&T department, without which, external researchers would not have been able to implement, or assess, such a large-scale experiment. Therefore, the buy-in of key staff members such as the Chief Minister’s office, the Secretary of the E&T department, as well as E&T Directors for different regions in Punjab was critical.

- The credibility of the incentives: this implies that the government told tax staff that they would get bonuses based on their performance, and after the staff had worked for the bonus, these bonuses were actually given to them. If the government had failed to do so, the staff would not have trusted in the government’s promises in the future. This is a key reason why increases in tax collection were larger in the second year of the project as compared to the first.

- Large incentives nudged property tax officials to perform their duties more effectively, leading to increased assessment and collection.

- It is common in developing countries for taxpayers to collude with tax collectors, with taxpayers paying collectors bribes to reduce their overall tax, leading to a win-win for both parties. The substantial cash incentives might have been higher than payments being received by officials from taxpayers, leading tax collectors to collect more taxes to increase their bonuses, instead of receiving bribes from taxpayers.

- The experiment showed that tax collectors targeted taxpayers with large taxable potential, rather than small property owners. This increased both overall collection and their bonuses more than it would have had the collectors invested the same energy in targeting smaller taxpayers.

Can it be replicated and continued?

As discussed earlier, the take-up of the project by the Punjab government and specifically, the Excise & Taxation department was critical to its success. Whether such an incentives scheme is sustainable is another matter altogether. The project’s technical details were devised by a group of academics at top academic institutions. These academics who were well-versed in the art of conducting such experiments, were assisted by a team of highly-skilled researchers in Lahore. Developing and retaining such human capital at government departments is not a simple task, given the differentials in incentives provided by academic and governmental organizations. Therefore, it is unlikely that the design of the project can be perpetuated by on-the-ground officials who have a different skill set and expertise. Further, for the duration of the project, it was protected from political and bureaucratic considerations, to the best of the ability of those at the top of the department. However, with the project moving solely into the domain of the department, without external assistance and accountability, it will be much harder for the E&T department to prevent incentives to be tailored in a way which “makes everyone happy”. This would appear to be the biggest challenge for using incentives to generate similar revenue gains.

However, if such challenges can be overcome, a financial incentives structure for tax collectors has tremendous potential to improve tax collection, not just in Punjab province, but in other regions as well. Counterparts to the E&T department in KPK, Sindh and Balochistan can exploit similar incentives, suited to the provincial context, to generate gains in revenue-collection. Such out-of-the-box mechanisms can contribute to correcting Pakistan’s revenue-generation trajectory, providing greater funds for investing into public goods such as health, education, water & sanitation, and infrastructure.