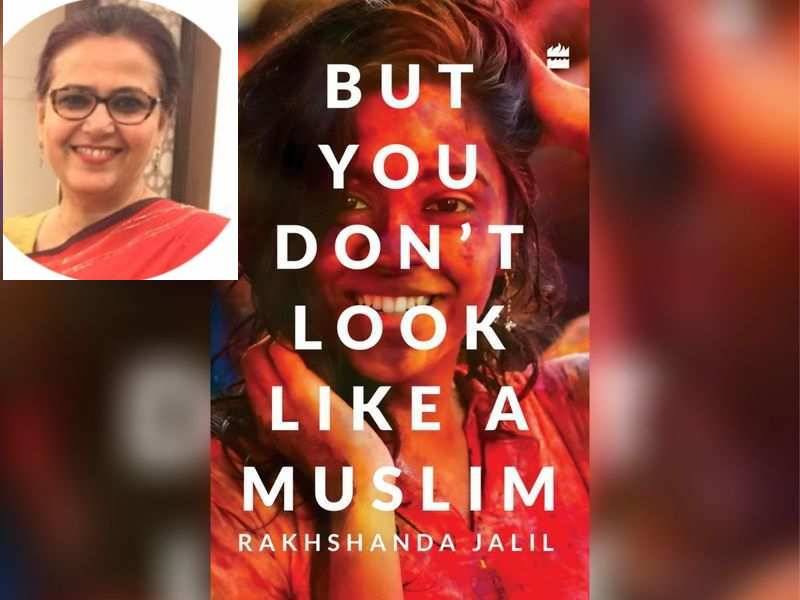

Rakshanda Jalil's recent book But You Don’t Look Like a Muslim is a compilation of insightful essays on identity and culture in contemporary India. Jalil has published over twenty books and written over fifty academic papers and essays. Her book on the lesser-known monuments of Delhi, Invisible City, continues to be a bestseller. Her most recent works include: the translations The Sea Lies Ahead, Intizar Husain’s seminal novel on Karachi, and Traitor, Krishan Chander’s Partition novel; an edited volume of critical writings on Ismat Chughtai called An Uncivil Woman; and a literary biography of the Urdu poet Shahryar.

My Father did not take the Train to Pakistan

I was eight years old in 1971. I remember the brown paper pasted on our windowpanes, the trenches dug in the park facing our house in a South Delhi neighborhood and the near-palpable fear of air strikes that held us in thrall. I also remember being called a ‘Paki’ by other kids in school as India and Pakistan prepared to go to war against each other yet again, or at least the only time in living memory for my generation. Being the only Muslim child in class, many of my peers, a Kashmiri Pandit boy in particular, took great delight in grilling me on my Pak connections. I tried, in vain, to explain that I had none. But no one would believe my stoic denials; I was a Muslim after all, I must have relatives in Pakistan. My sympathies must necessarily lie with ‘them’. And this tacit sympathy – taken for granted by my young tormenters -- made me as much an enemy as ‘them’.

I remember coming home in tears one afternoon. I remember my father, a man of great good sense, sitting down with me and giving me a little spiel. That afternoon chat was to give form and shape to my sense of nationhood in more ways than I could then fathom. It was also to place me squarely on a trajectory that has allowed me to chart my destiny in 21st century India precisely as I wish – not out of defiance or head-on collision but with self-assurance and poise. My father started by telling me how he had to leave his home in Pilibhit, a small town in the Terai region bordering the foothills of the Himalayas, and find shelter in a mosque, how many homes in his neighbourhood were gutted, others were vacated almost overnight by families leaving for Pakistan, and his goggle-eyed surprise at first sight of the Sikh refugees who moved in to the houses abandoned by fleeing Muslims. While the option of going to Pakistan was there for him too, a newly qualified doctor from a prestigious colonial-era medical college in Lucknow, he chose not go. In choosing to stay back and raise a family here in this land where his forefathers had lived and died, he was putting down more roots, stronger and deeper into the soil that had sustained generations before him. Wear your identity, if you must, as a badge of courage not shame, he said.

He also gave the example of my mother’s father, Ale Ahmad Suroor, a well-known name in the world of Urdu letters, and his decision too to stay put despite the many inducements that were offered to qualified Muslim men from sharif families. The Land of the Pure held out many promises: a lecturer could become a professor, a professor a Vice-Chancellor, sons would get good jobs, daughters find better grooms and there would be peace and prosperity among one’s own sort. And yet, my mother’s family like my father’s, chose not to go. To be honest, I was later told, my grandmother – a formidably headstrong lady -- wanted to go, especially since many in her family had moved to Karachi. But my grandfather, then a Lecturer at Lucknow University, was adamant: his future and his children’s lay here in Hindustan. And so they stayed. In the face of plain good sense, some might say. Why? What made them stay when so many were going?

Over the years, I have had many occasions to dwell upon this -- both on the possible reasons and the implications of their decision. As I have grappled with my twin identities (am I an Indian Muslim or a Muslim Indian?), or tried not to sound defensive about my so-called liberalism, or struggled to accept the patronizing compliment of being a secular Muslim without cringing, I have wondered why families like mine, in the end, chose Jawaharlal Nehru over Mohammad Ali Jinnah.

Like many Muslims in India I have often wondered if the cleavage of hearts and land was truly inevitable, or could it have been averted? What would have been the state of the Indian sub-continent today had a pact been reached between the Muslim League and the Congress? What happened to the heady days of 1919 when Hindus and Muslims had come together to fight the common enemy, the British? What went so wrong between the two major communities of the subcontinent? What caused the disenchantment with the Congress? What made some staunch Congressmen rally around the once-derided Muslim League? What cooled the Muslim’s ardour to join nationalistic mainstream politics? For that matter, why was the Muslim suddenly regarded as a toady and a coward content to let the Hindus fight for freedom from the imperial yoke? Why was he suddenly beyond the pale? How did he become the ‘other’? And what of the dream of the Muslim Renaissance spelt out in such soul-stirring verse by the visionary poet Iqbal? In turn, why did the Congress baulk at the issue of separate electorates, calling it absurd and retrograde? Why did it do nothing to allay the Muslim fear that the freedom promised by the Congress meant freedom for Hindus alone, not freedom for all? Seen from the Muslim point of view, the Congress appeared guilty of many sins of omission and some of commission. ‘Nationalism’ increasingly began to mean thinking and living in the Congress way and none other. Those who lived or thought another way came to be regarded as anti-national, especially in the years after independence.

However, to come back to the Muslim League and the extreme reactions it has always evoked among Indian Muslims, it is interesting to explore why the League logic enamoured some so completely and left others cold. When the Leaguers (or ‘Leaguii’ as they were referred to among Urdu speakers) first spoke of protecting the rights of the Muslims by securing fair representation in the legislature, they were giving voice to a long-felt need to recognize the Muslims as a distinct religious and political unit. On the face of it, these seemed perfectly legitimate aspirations; the problem, I suspect, lay in the manner in which the Muslim League went about its business. It employed a combination of rhetoric and religion to bludgeon its way. It used fear as a campaign tool, making Muslims view all Hindus as a ‘threat’ to their survival once independence was achieved and the ‘protective’ presence of the British removed. The sentiment behind Chaudhry Rahmat Ali’s pamphlet Now or Never: Are we to Live or Perish Forever? was echoed by countless volunteers – clad in the by-now trademark black shervani-white ‘Aligarh-cut’ pajama -- who saw themselves as soldiers in the “grim and fateful struggle against political crucifixion and complete annihilation”. They descended in droves on towns and hamlets all across Uttar Pradesh and Bihar where their speeches, delivered in chaste Urdu and peppered with suitably rousing verses penned by Iqbal and Mohamed Ali and Hafiz Jallundari, found rapt audiences and deep pockets. While a great many began to share their enthusiasm for the Muslim League and simple country women began to stitch League flags out of every available bit of green fabric, an equal number still held out. Quite a few were frankly unconvinced by the very notion of Muslims being a homogenized monolithic community that could be brought under the green banner unfurled by that most unlikely of all Muslim leaders – the Karachi-born, English-speaking, ultra-anglicised Jinnah. Many Muslims began to see the bogey of Hindu domination as exaggerated, others were uneasy with the theocratic underpinnings of the proposed new homeland. The Muslim League’s final unequivocal demand – a separate homeland – did not appeal to some Muslims for the same reasons of faulty logic. Jinnah’s assurance of providing constitutional safeguards to minorities appeared humbug in the face of his proclamation of a Pakistan that would be a hundred per cent Muslim. As Partition drew near and scores of Muslims, who had hitched their star to the wagon of the Muslim League, began to leave for the new homeland, families began to be divided, often with one sibling opting for Pakistan and, as it were, choosing Jinnah over Nehru, and the other digging their heels in and putting their faith in a new secular nation.

In the end, while it is clear why those who went did so, it is not always entirely evident why those who didn’t go chose to stay back. Was it gross sentiment or astute foresight that kept them back? Was the choice between Nehru over Jinnah made from the head or the heart? The generation that could have fully and satisfactorily answered these questions is either dead and gone or too frail to be disturbed by ghosts from a troubled past. Hoping to find some clues, I find myself turning the pages of my grandfather’s autobiography, Khwaab Baqui Hain (Dream Still Remain); his words bring me solace and hold out hope for my own future and that of my children:

I am a Musalman and, in the words of Maulana Azad, a “caretaker of the thirteen hundred years of the wealth that is Islam.” My deciphering of Islam is the key to the interpretation of my spirit. I am also an Indian and this Indianness is as much a part of my being. Islam does not deter me from believing in my Indian identity. Again, to quote Maulana Azad, if anything “it shows the way.” While it is true that I imbibed religion from my family and the environment in which I grew up, my own experiences and understanding made its foundations stronger. In Badayun, religion was the name for blind faith in traditionalism and age-old orthodoxies, miracles and marvels, faith healing by pirs and fakirs. I believe Belief in One God leads the way to equality among all mankind. Allah is not simply Rabbu’l-Muslimeen[‘the Lord of Muslims’]; He is also Rabbu’l Aalameen [‘the Lord of the World’]. The all-encompassing compactness of the personality of the Prophet of Islam has always drawn me. Islam doesn’t teach renunciation from the affairs of the world; it teaches us how to fulfill our duties in this world while at the same time instructing us to regard this mortal world as the field in which we sow the seeds for the Other World. There is no obduracy in Islam. I have seldom found obdurate people to be good human beings. The Islam that I know gives more importance to Huqooq-ul ibad [‘rights of the people’] rather than Huqooq-ul Lah [‘rights of God’].

I am hopeful that Islam will ‘show the way’ as, indeed it did for my grandfather -- a much-feted Urdu writer, critic, poet and teacher -- and will in no way deter me from believing in my Indian identity as much as in my religious one.

As I clock in a half century and more, I find I have done my share of soul searching and raking over the ashes. I am done, too, with defensive or aggressive posturing, or the equally ridiculous sitting-on-the-fence. Life has come full circle. My daughters went to the same school and university as I did. The clamorous unruly Jana Sangh of my childhood has been replaced by the Bharatiya Janta Party, a stronger, more vociferous, yet no less militant face of the Hindu rightwing. My daughters meet their share of Muslim baiters. I have told them what my father said to me. As I watch them grow into confident young people, I know that they shall cope, as I did. That they shall enjoy the dual yet in no way conflicting identities – of being Muslim and being Indian in no particular order. Despite Ayodhya and Gujarat, despite the politicians who come and go spouting venom and spreading biases, despite the many bad jokes about katuas, despite the discrimination that is sometimes overt and often covert, I do feel, it is a good thing that families like mine chose not to hitch their star to the wagon of the Muslim League.

My Father did not take the Train to Pakistan

I was eight years old in 1971. I remember the brown paper pasted on our windowpanes, the trenches dug in the park facing our house in a South Delhi neighborhood and the near-palpable fear of air strikes that held us in thrall. I also remember being called a ‘Paki’ by other kids in school as India and Pakistan prepared to go to war against each other yet again, or at least the only time in living memory for my generation. Being the only Muslim child in class, many of my peers, a Kashmiri Pandit boy in particular, took great delight in grilling me on my Pak connections. I tried, in vain, to explain that I had none. But no one would believe my stoic denials; I was a Muslim after all, I must have relatives in Pakistan. My sympathies must necessarily lie with ‘them’. And this tacit sympathy – taken for granted by my young tormenters -- made me as much an enemy as ‘them’.

I remember coming home in tears one afternoon. I remember my father, a man of great good sense, sitting down with me and giving me a little spiel. That afternoon chat was to give form and shape to my sense of nationhood in more ways than I could then fathom. It was also to place me squarely on a trajectory that has allowed me to chart my destiny in 21st century India precisely as I wish – not out of defiance or head-on collision but with self-assurance and poise. My father started by telling me how he had to leave his home in Pilibhit, a small town in the Terai region bordering the foothills of the Himalayas, and find shelter in a mosque, how many homes in his neighbourhood were gutted, others were vacated almost overnight by families leaving for Pakistan, and his goggle-eyed surprise at first sight of the Sikh refugees who moved in to the houses abandoned by fleeing Muslims. While the option of going to Pakistan was there for him too, a newly qualified doctor from a prestigious colonial-era medical college in Lucknow, he chose not go. In choosing to stay back and raise a family here in this land where his forefathers had lived and died, he was putting down more roots, stronger and deeper into the soil that had sustained generations before him. Wear your identity, if you must, as a badge of courage not shame, he said.

He also gave the example of my mother’s father, Ale Ahmad Suroor, a well-known name in the world of Urdu letters, and his decision too to stay put despite the many inducements that were offered to qualified Muslim men from sharif families. The Land of the Pure held out many promises: a lecturer could become a professor, a professor a Vice-Chancellor, sons would get good jobs, daughters find better grooms and there would be peace and prosperity among one’s own sort. And yet, my mother’s family like my father’s, chose not to go. To be honest, I was later told, my grandmother – a formidably headstrong lady -- wanted to go, especially since many in her family had moved to Karachi. But my grandfather, then a Lecturer at Lucknow University, was adamant: his future and his children’s lay here in Hindustan. And so they stayed. In the face of plain good sense, some might say. Why? What made them stay when so many were going?

Over the years, I have had many occasions to dwell upon this -- both on the possible reasons and the implications of their decision. As I have grappled with my twin identities (am I an Indian Muslim or a Muslim Indian?), or tried not to sound defensive about my so-called liberalism, or struggled to accept the patronizing compliment of being a secular Muslim without cringing, I have wondered why families like mine, in the end, chose Jawaharlal Nehru over Mohammad Ali Jinnah.

Like many Muslims in India I have often wondered if the cleavage of hearts and land was truly inevitable, or could it have been averted? What would have been the state of the Indian sub-continent today had a pact been reached between the Muslim League and the Congress? What happened to the heady days of 1919 when Hindus and Muslims had come together to fight the common enemy, the British? What went so wrong between the two major communities of the subcontinent? What caused the disenchantment with the Congress? What made some staunch Congressmen rally around the once-derided Muslim League? What cooled the Muslim’s ardour to join nationalistic mainstream politics? For that matter, why was the Muslim suddenly regarded as a toady and a coward content to let the Hindus fight for freedom from the imperial yoke? Why was he suddenly beyond the pale? How did he become the ‘other’? And what of the dream of the Muslim Renaissance spelt out in such soul-stirring verse by the visionary poet Iqbal? In turn, why did the Congress baulk at the issue of separate electorates, calling it absurd and retrograde? Why did it do nothing to allay the Muslim fear that the freedom promised by the Congress meant freedom for Hindus alone, not freedom for all? Seen from the Muslim point of view, the Congress appeared guilty of many sins of omission and some of commission. ‘Nationalism’ increasingly began to mean thinking and living in the Congress way and none other. Those who lived or thought another way came to be regarded as anti-national, especially in the years after independence.

However, to come back to the Muslim League and the extreme reactions it has always evoked among Indian Muslims, it is interesting to explore why the League logic enamoured some so completely and left others cold. When the Leaguers (or ‘Leaguii’ as they were referred to among Urdu speakers) first spoke of protecting the rights of the Muslims by securing fair representation in the legislature, they were giving voice to a long-felt need to recognize the Muslims as a distinct religious and political unit. On the face of it, these seemed perfectly legitimate aspirations; the problem, I suspect, lay in the manner in which the Muslim League went about its business. It employed a combination of rhetoric and religion to bludgeon its way. It used fear as a campaign tool, making Muslims view all Hindus as a ‘threat’ to their survival once independence was achieved and the ‘protective’ presence of the British removed. The sentiment behind Chaudhry Rahmat Ali’s pamphlet Now or Never: Are we to Live or Perish Forever? was echoed by countless volunteers – clad in the by-now trademark black shervani-white ‘Aligarh-cut’ pajama -- who saw themselves as soldiers in the “grim and fateful struggle against political crucifixion and complete annihilation”. They descended in droves on towns and hamlets all across Uttar Pradesh and Bihar where their speeches, delivered in chaste Urdu and peppered with suitably rousing verses penned by Iqbal and Mohamed Ali and Hafiz Jallundari, found rapt audiences and deep pockets. While a great many began to share their enthusiasm for the Muslim League and simple country women began to stitch League flags out of every available bit of green fabric, an equal number still held out. Quite a few were frankly unconvinced by the very notion of Muslims being a homogenized monolithic community that could be brought under the green banner unfurled by that most unlikely of all Muslim leaders – the Karachi-born, English-speaking, ultra-anglicised Jinnah. Many Muslims began to see the bogey of Hindu domination as exaggerated, others were uneasy with the theocratic underpinnings of the proposed new homeland. The Muslim League’s final unequivocal demand – a separate homeland – did not appeal to some Muslims for the same reasons of faulty logic. Jinnah’s assurance of providing constitutional safeguards to minorities appeared humbug in the face of his proclamation of a Pakistan that would be a hundred per cent Muslim. As Partition drew near and scores of Muslims, who had hitched their star to the wagon of the Muslim League, began to leave for the new homeland, families began to be divided, often with one sibling opting for Pakistan and, as it were, choosing Jinnah over Nehru, and the other digging their heels in and putting their faith in a new secular nation.

In the end, while it is clear why those who went did so, it is not always entirely evident why those who didn’t go chose to stay back. Was it gross sentiment or astute foresight that kept them back? Was the choice between Nehru over Jinnah made from the head or the heart? The generation that could have fully and satisfactorily answered these questions is either dead and gone or too frail to be disturbed by ghosts from a troubled past. Hoping to find some clues, I find myself turning the pages of my grandfather’s autobiography, Khwaab Baqui Hain (Dream Still Remain); his words bring me solace and hold out hope for my own future and that of my children:

I am a Musalman and, in the words of Maulana Azad, a “caretaker of the thirteen hundred years of the wealth that is Islam.” My deciphering of Islam is the key to the interpretation of my spirit. I am also an Indian and this Indianness is as much a part of my being. Islam does not deter me from believing in my Indian identity. Again, to quote Maulana Azad, if anything “it shows the way.” While it is true that I imbibed religion from my family and the environment in which I grew up, my own experiences and understanding made its foundations stronger. In Badayun, religion was the name for blind faith in traditionalism and age-old orthodoxies, miracles and marvels, faith healing by pirs and fakirs. I believe Belief in One God leads the way to equality among all mankind. Allah is not simply Rabbu’l-Muslimeen[‘the Lord of Muslims’]; He is also Rabbu’l Aalameen [‘the Lord of the World’]. The all-encompassing compactness of the personality of the Prophet of Islam has always drawn me. Islam doesn’t teach renunciation from the affairs of the world; it teaches us how to fulfill our duties in this world while at the same time instructing us to regard this mortal world as the field in which we sow the seeds for the Other World. There is no obduracy in Islam. I have seldom found obdurate people to be good human beings. The Islam that I know gives more importance to Huqooq-ul ibad [‘rights of the people’] rather than Huqooq-ul Lah [‘rights of God’].

I am hopeful that Islam will ‘show the way’ as, indeed it did for my grandfather -- a much-feted Urdu writer, critic, poet and teacher -- and will in no way deter me from believing in my Indian identity as much as in my religious one.

As I clock in a half century and more, I find I have done my share of soul searching and raking over the ashes. I am done, too, with defensive or aggressive posturing, or the equally ridiculous sitting-on-the-fence. Life has come full circle. My daughters went to the same school and university as I did. The clamorous unruly Jana Sangh of my childhood has been replaced by the Bharatiya Janta Party, a stronger, more vociferous, yet no less militant face of the Hindu rightwing. My daughters meet their share of Muslim baiters. I have told them what my father said to me. As I watch them grow into confident young people, I know that they shall cope, as I did. That they shall enjoy the dual yet in no way conflicting identities – of being Muslim and being Indian in no particular order. Despite Ayodhya and Gujarat, despite the politicians who come and go spouting venom and spreading biases, despite the many bad jokes about katuas, despite the discrimination that is sometimes overt and often covert, I do feel, it is a good thing that families like mine chose not to hitch their star to the wagon of the Muslim League.