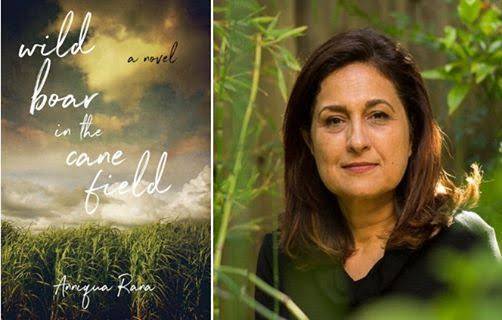

Anniqua Rana lives in California with her husband and two sons. She has taught English to immigrant and international students at community college for over twenty years. Her extended family lives in Pakistan and England, and she visits them regularly to rekindle her roots. Her debut novel, Wild Boar in the Cane Field, is a celebration of the rural women of Pakistan whose indomitable spirit keeps them struggling against all odds. She has interviewed Asma Jahangir, Human Rights Lawyer, Pakistan, and published essays on gender and education. She is working on her next novel A Sanctuary for Dancing Bears.

Raza Raja: I have read several reviews and so far, your novel has been receiving good amount of critical acclaim. So why do you think that your attempt has resonated so much with the critics?

Anniqua Rana: Why all this attention and such a great response? First, not many novels in English have been written about rural South Asia with strong female characters with the resilience of Tara, Bhaggan, and all the women around them. This one reason is unique to readers – both locally and internationally.

Then, the story is of real human beings with desires that everyone feels the need to belong, the need to love, the need to be recognised. And the conflicts are also familiar: cultural restrictions and personal needs. Readers have told me that they know a Bhaggan, she might not have been called by that name, but they know of someone like her, who has spent her whole life serving others in a kitchen that is not even her own. And these are people from very different backgrounds.

And lastly, I think my writing style and use of imagery and metaphors might have helped reviewers feel the environment. For a reader to enjoy the reading experience, it is important that they become a part of the world that the writer creates.

RR: What’s the inspiration behind the title of your book, Wild Boar in the Cane Field?

AN: It’s a Punjabi phrase that I heard growing up on the farm in Faisalabad. At the time, I didn't realise the uniqueness of the life I was living. Our life, controlled by the nature around us, was very different from that of my friends living in the city.

In the winter, we would take long walks to the cane fields. And, there, if we were lucky, farmhands, who were making cane sugar, would make cane toffee that we would fill in a bucket and take home. As we walked past the fields, they would break sugar canes, and we would use our teeth to peel them. We were told this would make our teeth stronger. I’m not sure about the science behind it, but it made for a very interesting walk, and, fingers crossed, my teeth are still in good shape.

The fear, however, was during harvest time; the boar hidden in the fields would look for places to hide their young and in doing so would attack humans. Even though there have been many cases of boar attacking humans around the country, I don’t remember hearing of such a case on the farm where we lived. The menace, however, was prevalent. The fear of the unknown was greater than the tragedy of reality. That is what I wanted to portray in the story. Also, those we fear sometimes live in their own insecurity. We just have to accept it.

RR: You are a part of US-based Pakistani diaspora, although born and initially educated in Pakistan. One would expect such an individual to write a novel which is somehow reflective of her experience as a first-generation Muslim immigrant woman in USA. However, you chose to write about rural Pakistan. What motivated you to write about that?

AN: The song goes, “I left my heart in San Francisco”, but for me, I live twenty miles south of San Francisco, and my spirit is still in Pakistan. Even though I have lived here for over thirty years and call it my home, I return regularly to Pakistan.

I also have a strong connection with England. My mother is British and moved to Pakistan when she married my father. We spent a few years in England when I was growing up. I have always been on the boundaries of cultures, British, Pakistani, and USA, with all their multiplicities. And I have benefitted from it.

I enjoy reading books about the immigrant experience. A Place for Us, by Fatima Mirza is one that resonated with me. And the experiences are very real and sometimes painful. I teach English to international and immigrant students and am very much part of their stories of separation, pain, and opportunities, shaping their lives and those they connect with in unimaginable ways.

I might one day write about those experiences, particularly the complexity of learning to communicate in new languages in different ways. Dreams of returning. Reality of staying. Barriers of documentation.

The geographical boundaries, however, are man-made. Not many women or other genders have been part of the politics of nations. But these man-made boundaries can be very restrictive, confining, stifling. Mohsin Hamid wrote a beautiful article about this concept which is titled “In the 21st century, we are all migrants”. This is the truth of our new reality.

A few years back, I started writing a memoir of my time in Faisalabad, and then, I realised, for my first book, I wanted complete freedom to create a world of my own. A world with people that spoke to me in ways I hadn’t imagined.

And then I wanted the flies to play an important part. I wanted to make a shrine for them, “The Shrine of Sain Makhianwala”. I wrote this story to provide a window to experiences that are not usually documented.

RR: Unfortunately, many in Pakistan, generally think rural people as very backward and even ignorant. However, your book does dispel this notion somewhat. Do you think that general perception about rural Pakistan is too cliched?

AN: Approximately only half the population of Pakistan is literate because of lack of educational opportunities. This is not surprising considering the minimal amount of public funding for education. The gender disparity in rural areas is much worse than urban areas

But that doesn't mean that people living in rural areas are not aware of these disparities. In fact, one of my character, Bhaggan’s dream for her eldest son Sultan and her other sons is that they will go to school and lift the family out of their servitude which seems to be their fate.

The setting of Tara’s story is the pre-cell phone era Punjab. Now, with access to the world through cell phones, the awareness of the disparity is even more profound.

I spent last summer in Pakistan and had the opportunity to discuss such matters to get first-hand accounts. One young man mentioned that his wife had chosen to leave the village because of lack of educational opportunities for their children. She was renting a place in a small town, which was financially more feasible than moving to Lahore with her husband. Because she was educated till eighth grade, she was going to make sure her children would go to college.

And then my sister tells me about a young woman in her design and manufacturing company for the apparel industry in rural Punjab. Most of the women in the company are semi-literate and all are from rural areas. When being trained on the marketing for the industry, the young woman expressed her interest in modeling. She was asked to check with her parents, and their response was, “Will someone pull you out of a photo? Of course not. Go ahead.” Such common sense response is not the norm in more conservative settings. These young women use Youtube to learn about the industry and are primarily self-taught.

So to answer your question, yes. Any stereotype is too simplistic to gauge a society.

RR: Many of your characters appear extremely real including the central character “Tara”. Are some of these inspired by some real individuals you happened to know?

AN: The interactions we have with others always has an impact on our imagination. As I wrote the novel, one of the most enriching elements was of creating a world that does not exist, but could, very likely exist in the vast expanse of the Punjab, or probably any place in South Asia.

Similarly, the characters could very well exist, but they were all a deliberate fictional creation of characteristics that I have observed in people across the world.

Everyone feels envy. Everyone has ambition, but what makes these characters unique is the situation I have placed them in and how they respond to what happens around them.

Saffiya, the landowner, is married to a man who is of the same caste and owns some land. Her father isn’t concerned that he is much older and is, most likely in the late stages of some undiagnosed sickness, most likely tuberculosis. He is also still mourning the death of his first wife and two children who seemed to have died of the same illness. Saffiya is relieved that his death allows her to return to her home.

Tara wants a family but she doesn't want the one that others are creating for her, she wants to create her own. She wants life on her terms. This is a common experience regardless of time and place.

The characters are not based on any individuals, rather are created to inhabit the world that they live in.

RR: In general, at least in Pakistani TV dramas, the heroines are damsels in distress with very conservative sexual morals. However, your central character Tara, is rebellious (despite heavy odds stacked against her) and is “flawed” at least by traditional standards as she is also ready to explore her sexuality. Moreover, she is at times mean to others and ready to steal. So, what’s the rationale behind creating such a character? In other words, what kind of character is Tara?

AN: When I began writing this story, I decided that the female characters would be true to the strong women I have observed in rural Pakistan. Despite the challenges that are thrown their way, they demonstrate a level of perseverance that is exemplary.

I wouldn’t call Tara flawed, she is like any strong young woman finding her place in a restrictive society. Similar to any reflective young person, in this case a woman, Tara rebels against the decision she knows will cause her harm. Self-preservation is an act of common sense. She is not a victim. She chooses to take control of her life when she is very young. As she grows older, she takes risks because she knows that the adults around her are making decisions which are not in her best interest. Granted, she’s not always sure of the outcomes of her actions, but she knows that if things go wrong, she will not blame others. She takes responsibility for her actions. That is what is admirable in her.

As far as her sexuality is concerned, it is the normal teenage hormone induced awareness of the opposite sex. The media tends to present a male perspective and it is high time that women share their true reality rather than be portrayed through a male lens.

RR: Do you think that we as a society have strong prejudice against certain minorities? In your novel there are subtle hints, particularly about Christians.

I was compelled to include the relationship between Maria, a Christian, and Tara, a Muslim, and their tender inter-connectedness, which should be the norm, and in many cases it is. However, there are those who prefer to focus on differences rather than similarities. Rather than acknowledging the human relationships, some feel the need to discriminate against people because their beliefs are different from the majority, despite consensus that all humans are created equal. These perspectives are carried from one generation to the next without being questioned, because questioning tradition is interpreted as disrespect.

RR: Why do flies feature so prominently in your narrative?

Flies are everywhere in the Punjab. They hover consistently. Instead of swatting them, I chose to make them integral to this story. Tara is found covered in flies in the opening scene of her life.

But it’s not only the omnipresence of flies that compelled me to make them central to the story of Tara and the villagers in Saffiya’s ancestral village, Tara’s home. Granted they have short lives but they are soon re-incarnated. Their vision is a 360-degree-view of the world focusing on shapes, motion, and color differently. Flies are able to see light in a way humans cannot. A fly's vision has often been compared to a mosaic -- thousands of tiny images combining to represent one visual image.

In addition to their vision, flies use taste to know their surroundings. They see and sense the world in a unique way, and despite their short lifetime, they manage to accomplish quite a lot for such a tiny insect.

To protect the flies of Tara’s world, I created the Shrine of Sain Makhianwala, the keeper of the flies, where flies are venerated.

It is not uncommon to find shrines dedicated to animals in South Asia. The revered saint of such shrines is known to have protected alligators, dogs to name a few lucky animals, so why not a sanctuary for flies?

In the last section of the novel, the flies narrate the hidden intricacies that only a fly on the wall could know.

RR: If there is one major takeaway from your novel, what is that? I mean, what is the central message you want to give?

People in rural South Asia, particularly women, exemplify the human capacity to overcome the menacing unknown while connecting with their surroundings and supporting each other.

Raza Raja: I have read several reviews and so far, your novel has been receiving good amount of critical acclaim. So why do you think that your attempt has resonated so much with the critics?

Anniqua Rana: Why all this attention and such a great response? First, not many novels in English have been written about rural South Asia with strong female characters with the resilience of Tara, Bhaggan, and all the women around them. This one reason is unique to readers – both locally and internationally.

Then, the story is of real human beings with desires that everyone feels the need to belong, the need to love, the need to be recognised. And the conflicts are also familiar: cultural restrictions and personal needs. Readers have told me that they know a Bhaggan, she might not have been called by that name, but they know of someone like her, who has spent her whole life serving others in a kitchen that is not even her own. And these are people from very different backgrounds.

And lastly, I think my writing style and use of imagery and metaphors might have helped reviewers feel the environment. For a reader to enjoy the reading experience, it is important that they become a part of the world that the writer creates.

RR: What’s the inspiration behind the title of your book, Wild Boar in the Cane Field?

AN: It’s a Punjabi phrase that I heard growing up on the farm in Faisalabad. At the time, I didn't realise the uniqueness of the life I was living. Our life, controlled by the nature around us, was very different from that of my friends living in the city.

In the winter, we would take long walks to the cane fields. And, there, if we were lucky, farmhands, who were making cane sugar, would make cane toffee that we would fill in a bucket and take home. As we walked past the fields, they would break sugar canes, and we would use our teeth to peel them. We were told this would make our teeth stronger. I’m not sure about the science behind it, but it made for a very interesting walk, and, fingers crossed, my teeth are still in good shape.

The fear, however, was during harvest time; the boar hidden in the fields would look for places to hide their young and in doing so would attack humans. Even though there have been many cases of boar attacking humans around the country, I don’t remember hearing of such a case on the farm where we lived. The menace, however, was prevalent. The fear of the unknown was greater than the tragedy of reality. That is what I wanted to portray in the story. Also, those we fear sometimes live in their own insecurity. We just have to accept it.

RR: You are a part of US-based Pakistani diaspora, although born and initially educated in Pakistan. One would expect such an individual to write a novel which is somehow reflective of her experience as a first-generation Muslim immigrant woman in USA. However, you chose to write about rural Pakistan. What motivated you to write about that?

AN: The song goes, “I left my heart in San Francisco”, but for me, I live twenty miles south of San Francisco, and my spirit is still in Pakistan. Even though I have lived here for over thirty years and call it my home, I return regularly to Pakistan.

I also have a strong connection with England. My mother is British and moved to Pakistan when she married my father. We spent a few years in England when I was growing up. I have always been on the boundaries of cultures, British, Pakistani, and USA, with all their multiplicities. And I have benefitted from it.

I enjoy reading books about the immigrant experience. A Place for Us, by Fatima Mirza is one that resonated with me. And the experiences are very real and sometimes painful. I teach English to international and immigrant students and am very much part of their stories of separation, pain, and opportunities, shaping their lives and those they connect with in unimaginable ways.

I might one day write about those experiences, particularly the complexity of learning to communicate in new languages in different ways. Dreams of returning. Reality of staying. Barriers of documentation.

The geographical boundaries, however, are man-made. Not many women or other genders have been part of the politics of nations. But these man-made boundaries can be very restrictive, confining, stifling. Mohsin Hamid wrote a beautiful article about this concept which is titled “In the 21st century, we are all migrants”. This is the truth of our new reality.

A few years back, I started writing a memoir of my time in Faisalabad, and then, I realised, for my first book, I wanted complete freedom to create a world of my own. A world with people that spoke to me in ways I hadn’t imagined.

And then I wanted the flies to play an important part. I wanted to make a shrine for them, “The Shrine of Sain Makhianwala”. I wrote this story to provide a window to experiences that are not usually documented.

RR: Unfortunately, many in Pakistan, generally think rural people as very backward and even ignorant. However, your book does dispel this notion somewhat. Do you think that general perception about rural Pakistan is too cliched?

AN: Approximately only half the population of Pakistan is literate because of lack of educational opportunities. This is not surprising considering the minimal amount of public funding for education. The gender disparity in rural areas is much worse than urban areas

But that doesn't mean that people living in rural areas are not aware of these disparities. In fact, one of my character, Bhaggan’s dream for her eldest son Sultan and her other sons is that they will go to school and lift the family out of their servitude which seems to be their fate.

The setting of Tara’s story is the pre-cell phone era Punjab. Now, with access to the world through cell phones, the awareness of the disparity is even more profound.

I spent last summer in Pakistan and had the opportunity to discuss such matters to get first-hand accounts. One young man mentioned that his wife had chosen to leave the village because of lack of educational opportunities for their children. She was renting a place in a small town, which was financially more feasible than moving to Lahore with her husband. Because she was educated till eighth grade, she was going to make sure her children would go to college.

And then my sister tells me about a young woman in her design and manufacturing company for the apparel industry in rural Punjab. Most of the women in the company are semi-literate and all are from rural areas. When being trained on the marketing for the industry, the young woman expressed her interest in modeling. She was asked to check with her parents, and their response was, “Will someone pull you out of a photo? Of course not. Go ahead.” Such common sense response is not the norm in more conservative settings. These young women use Youtube to learn about the industry and are primarily self-taught.

So to answer your question, yes. Any stereotype is too simplistic to gauge a society.

RR: Many of your characters appear extremely real including the central character “Tara”. Are some of these inspired by some real individuals you happened to know?

AN: The interactions we have with others always has an impact on our imagination. As I wrote the novel, one of the most enriching elements was of creating a world that does not exist, but could, very likely exist in the vast expanse of the Punjab, or probably any place in South Asia.

Similarly, the characters could very well exist, but they were all a deliberate fictional creation of characteristics that I have observed in people across the world.

Everyone feels envy. Everyone has ambition, but what makes these characters unique is the situation I have placed them in and how they respond to what happens around them.

Saffiya, the landowner, is married to a man who is of the same caste and owns some land. Her father isn’t concerned that he is much older and is, most likely in the late stages of some undiagnosed sickness, most likely tuberculosis. He is also still mourning the death of his first wife and two children who seemed to have died of the same illness. Saffiya is relieved that his death allows her to return to her home.

Tara wants a family but she doesn't want the one that others are creating for her, she wants to create her own. She wants life on her terms. This is a common experience regardless of time and place.

The characters are not based on any individuals, rather are created to inhabit the world that they live in.

RR: In general, at least in Pakistani TV dramas, the heroines are damsels in distress with very conservative sexual morals. However, your central character Tara, is rebellious (despite heavy odds stacked against her) and is “flawed” at least by traditional standards as she is also ready to explore her sexuality. Moreover, she is at times mean to others and ready to steal. So, what’s the rationale behind creating such a character? In other words, what kind of character is Tara?

AN: When I began writing this story, I decided that the female characters would be true to the strong women I have observed in rural Pakistan. Despite the challenges that are thrown their way, they demonstrate a level of perseverance that is exemplary.

I wouldn’t call Tara flawed, she is like any strong young woman finding her place in a restrictive society. Similar to any reflective young person, in this case a woman, Tara rebels against the decision she knows will cause her harm. Self-preservation is an act of common sense. She is not a victim. She chooses to take control of her life when she is very young. As she grows older, she takes risks because she knows that the adults around her are making decisions which are not in her best interest. Granted, she’s not always sure of the outcomes of her actions, but she knows that if things go wrong, she will not blame others. She takes responsibility for her actions. That is what is admirable in her.

As far as her sexuality is concerned, it is the normal teenage hormone induced awareness of the opposite sex. The media tends to present a male perspective and it is high time that women share their true reality rather than be portrayed through a male lens.

RR: Do you think that we as a society have strong prejudice against certain minorities? In your novel there are subtle hints, particularly about Christians.

I was compelled to include the relationship between Maria, a Christian, and Tara, a Muslim, and their tender inter-connectedness, which should be the norm, and in many cases it is. However, there are those who prefer to focus on differences rather than similarities. Rather than acknowledging the human relationships, some feel the need to discriminate against people because their beliefs are different from the majority, despite consensus that all humans are created equal. These perspectives are carried from one generation to the next without being questioned, because questioning tradition is interpreted as disrespect.

RR: Why do flies feature so prominently in your narrative?

Flies are everywhere in the Punjab. They hover consistently. Instead of swatting them, I chose to make them integral to this story. Tara is found covered in flies in the opening scene of her life.

But it’s not only the omnipresence of flies that compelled me to make them central to the story of Tara and the villagers in Saffiya’s ancestral village, Tara’s home. Granted they have short lives but they are soon re-incarnated. Their vision is a 360-degree-view of the world focusing on shapes, motion, and color differently. Flies are able to see light in a way humans cannot. A fly's vision has often been compared to a mosaic -- thousands of tiny images combining to represent one visual image.

In addition to their vision, flies use taste to know their surroundings. They see and sense the world in a unique way, and despite their short lifetime, they manage to accomplish quite a lot for such a tiny insect.

To protect the flies of Tara’s world, I created the Shrine of Sain Makhianwala, the keeper of the flies, where flies are venerated.

It is not uncommon to find shrines dedicated to animals in South Asia. The revered saint of such shrines is known to have protected alligators, dogs to name a few lucky animals, so why not a sanctuary for flies?

In the last section of the novel, the flies narrate the hidden intricacies that only a fly on the wall could know.

RR: If there is one major takeaway from your novel, what is that? I mean, what is the central message you want to give?

People in rural South Asia, particularly women, exemplify the human capacity to overcome the menacing unknown while connecting with their surroundings and supporting each other.