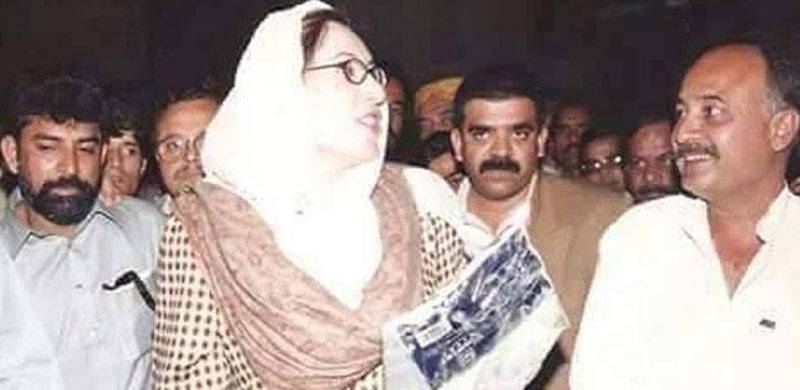

On the evening of August 6th, 1990, President of Pakistan Ghulam Ishaq Khan called an emergency press conference at the Aiwan-e-Sadr (President House). At 5 o’clock, and with all three of the joint chiefs of staff of the armed forces present, the President declared that he was dismissing the government of Benazir Bhutto and dissolving the elected National Assembly using his powers under article 58 2(b) of the constitution.

The story of this dismissal is really quite interesting because it gives us an insight into the sort of opposition a civilian government faced in the 90’s from an establishment dominated by supporters of General Zia and the army, and the role of media in political maneuvering and machinations.

For instance, Ghulam Ishaq Khan made his explosive announcement at 5 in the evening, yet the whole political machinery of Islamabad had been in uproar since the morning because The Nation, an English-language daily, had printed a story in that day’s edition pointing to the possibility of such a dismissal. All day, officials of the civilian government frantically searched for confirmation or denial of the news. When one of them contacted Arif Nizami, the reporter who had filed the Nation story to ask him about his source, Nizami told him to worry about saving his government rather than talking to him.

The president’s office denied the news, and, during the day, Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto presided over a meeting of the Economic Coordination Committee of the Cabinet. Yet during the afternoon, a sizable mobilization of troops around Islamabad was seen and armed units occupied Prime Ministerial Secretariat, Pakistan Television Center (PTV), Radio Pakistan and other strategic places. At a quarter to 5, just before his public announcement, the President called Benazir Bhutto and told her he was going to dismiss her government. When asked why he had denied the Nation report when was asked in the morning, he said the decision had been made in the afternoon.

Yet it is quite clear that the decision had been made much earlier. At the time, sources within the military had reported that it had been decided to remove Benazir, but the way they wanted to go about it was political maneuvering within the parliament. Eight months earlier, during November of 1988, such an attempt was made when agents linked to ISI had tried to bribe assembly members and buy their votes for a motion of Non-Confidence.

The government, using similar tactics, somehow survived, and the two men tried for this attempt were duly disowned and their relation to ISI denied. Apparently, Brigadier Imtiaz “Billa” Ahmed and Major Amir were working on their own and had even financed the crores of rupees used by themselves.

Rumors of the government’s dismissal had been circulating for weeks before the actual announcement, and speculation was rife, yet the dismissal still came as a surprise. The decision to use article 58 2(b) of the constitution and dismiss the government through a presidential order rather than a vote of Non-Confidence, had been made a few days before August 6.

But Why?

Why did the Army and the President decide to dismiss the government? Different reasons are put forward by different people since there was a multitude of things on which the army and the government clashed. The dismissal of General Hameed Gul as head of ISI, for one, had been received very badly by the armed forces. Then there was difficult situation in Sindh where, People's Party was feuding with erstwhile ally, MQM, and after the bloody events of Pakka Qilla, the army had wanted to take control of the province through Article 245 of the constitution. But this had been blocked by PPP. Amongst all this, foreign policy was maybe the severest point of contention between the government and the armed forces. People's Party differed with the armed forces on its Afghan Policy, and also anted to improve relations with India. Rajiv Gandhi and his wife had even visited Islamabad in 1989, and such policies gave the Army an excuse to paint Benazir as a threat to national security and to say that the government was not serious with regards to the Kashmir problem.

Some analysts point to the inexperience of Benazir and her team in running a government, especially with regards to how they were not ready to face the remnants of Zia ul Haq’s eleven years in power. Maybe Benazir was too ethical in relation to the press and media at the time as well, giving her opponents room to fill the newspapers with propaganda and bad press against her government and her person, variously using religion, corruption, and incompetence as weapons against her public image. Either way, there was definitely a dearth of confidence between Benazir Bhutto and the armed forces; both were suspicious of each other, and both believed the other party to be subservient to themselves, and acted accordingly.

The above article is a translated summary of an Urdu article by Umber Khairi published on Naya Daur Urdu.

The story of this dismissal is really quite interesting because it gives us an insight into the sort of opposition a civilian government faced in the 90’s from an establishment dominated by supporters of General Zia and the army, and the role of media in political maneuvering and machinations.

For instance, Ghulam Ishaq Khan made his explosive announcement at 5 in the evening, yet the whole political machinery of Islamabad had been in uproar since the morning because The Nation, an English-language daily, had printed a story in that day’s edition pointing to the possibility of such a dismissal. All day, officials of the civilian government frantically searched for confirmation or denial of the news. When one of them contacted Arif Nizami, the reporter who had filed the Nation story to ask him about his source, Nizami told him to worry about saving his government rather than talking to him.

The president’s office denied the news, and, during the day, Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto presided over a meeting of the Economic Coordination Committee of the Cabinet. Yet during the afternoon, a sizable mobilization of troops around Islamabad was seen and armed units occupied Prime Ministerial Secretariat, Pakistan Television Center (PTV), Radio Pakistan and other strategic places. At a quarter to 5, just before his public announcement, the President called Benazir Bhutto and told her he was going to dismiss her government. When asked why he had denied the Nation report when was asked in the morning, he said the decision had been made in the afternoon.

Yet it is quite clear that the decision had been made much earlier. At the time, sources within the military had reported that it had been decided to remove Benazir, but the way they wanted to go about it was political maneuvering within the parliament. Eight months earlier, during November of 1988, such an attempt was made when agents linked to ISI had tried to bribe assembly members and buy their votes for a motion of Non-Confidence.

The government, using similar tactics, somehow survived, and the two men tried for this attempt were duly disowned and their relation to ISI denied. Apparently, Brigadier Imtiaz “Billa” Ahmed and Major Amir were working on their own and had even financed the crores of rupees used by themselves.

Rumors of the government’s dismissal had been circulating for weeks before the actual announcement, and speculation was rife, yet the dismissal still came as a surprise. The decision to use article 58 2(b) of the constitution and dismiss the government through a presidential order rather than a vote of Non-Confidence, had been made a few days before August 6.

But Why?

Why did the Army and the President decide to dismiss the government? Different reasons are put forward by different people since there was a multitude of things on which the army and the government clashed. The dismissal of General Hameed Gul as head of ISI, for one, had been received very badly by the armed forces. Then there was difficult situation in Sindh where, People's Party was feuding with erstwhile ally, MQM, and after the bloody events of Pakka Qilla, the army had wanted to take control of the province through Article 245 of the constitution. But this had been blocked by PPP. Amongst all this, foreign policy was maybe the severest point of contention between the government and the armed forces. People's Party differed with the armed forces on its Afghan Policy, and also anted to improve relations with India. Rajiv Gandhi and his wife had even visited Islamabad in 1989, and such policies gave the Army an excuse to paint Benazir as a threat to national security and to say that the government was not serious with regards to the Kashmir problem.

Some analysts point to the inexperience of Benazir and her team in running a government, especially with regards to how they were not ready to face the remnants of Zia ul Haq’s eleven years in power. Maybe Benazir was too ethical in relation to the press and media at the time as well, giving her opponents room to fill the newspapers with propaganda and bad press against her government and her person, variously using religion, corruption, and incompetence as weapons against her public image. Either way, there was definitely a dearth of confidence between Benazir Bhutto and the armed forces; both were suspicious of each other, and both believed the other party to be subservient to themselves, and acted accordingly.

Article 58 2(b) was used twice more during the 1990’s to dismiss elected governments on charges of incompetence and corruption; politicians were subjected to court cases and accusations, and the media was used as an ancillary to officialdom to achieve these effects. After Benazir was assassinated, and her husband, Asif Ali Zardari rode the storm tide of her martyrdom into power, the Peoples Party Government removed this amendment from the constitution. Yet, even without it, the tradition of ending elected governments and playing at political machinations continues. As they say, where there is a will, there is a way.

The above article is a translated summary of an Urdu article by Umber Khairi published on Naya Daur Urdu.