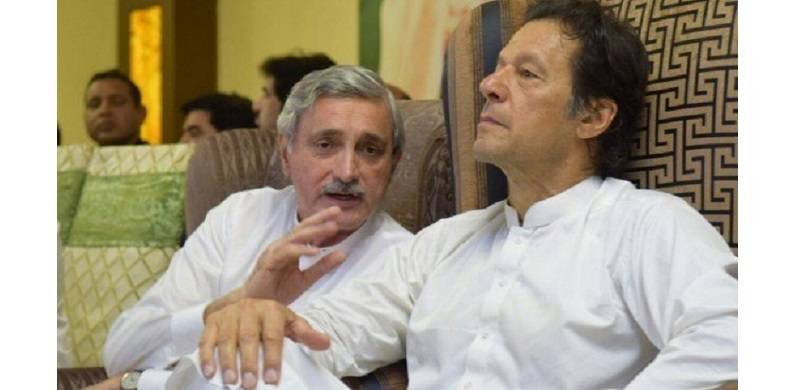

It is heartening to see a willingness on the part of Prime Minister Imran Khan's government to put in motion a process by which the country can find out more about about the sugar and wheat shortage of recent months. He has also called for the formation of a commission to investigate the sugar crisis and conduct a forensic audit of sugar mills – some of which are owned by figures at the highest level of the ruling party itself.

This would be a good time for the ruling party and its fierce partisans to reconsider what they understand by 'accountability'. It is unlikely that the ruling party would accept the claims of critics that the Prime Minister himself aided or abetted any wrongdoing that may have happened in this instance. Moreover, it is unlikely that the PM would acquiesce if there were any widespread calls from the opposition for him to step down on 'moral grounds' at any point. And this is also understandable.

But previous governments were not held to such reasonable standards by the current ruling party when it was in opposition. In fact, the PTI-led government continues to hound figures from previous governments over claims of wrongdoing which those individuals had just as much of a right to contest as PM Imran Khan does today. And yet, when those figures contested accusations against them, it was presented by the PTI as proof that no 'justice' or 'accountability' was possible until Imran Khan's revolution.

Herein lies the problem: we are well into the promised Naya Pakistan. And to nobody's surprise, it appears that the nexus between government organs and big business has not gone anywhere. The world continues to do business as business was always done.

This should not be an excuse for continued wrongdoing under any government. But surely we might ask the ruling party and its vociferous talking heads: are they holding themselves to a separate standard from their political opponents?

This would be a good time for the ruling party and its fierce partisans to reconsider what they understand by 'accountability'. It is unlikely that the ruling party would accept the claims of critics that the Prime Minister himself aided or abetted any wrongdoing that may have happened in this instance. Moreover, it is unlikely that the PM would acquiesce if there were any widespread calls from the opposition for him to step down on 'moral grounds' at any point. And this is also understandable.

But previous governments were not held to such reasonable standards by the current ruling party when it was in opposition. In fact, the PTI-led government continues to hound figures from previous governments over claims of wrongdoing which those individuals had just as much of a right to contest as PM Imran Khan does today. And yet, when those figures contested accusations against them, it was presented by the PTI as proof that no 'justice' or 'accountability' was possible until Imran Khan's revolution.

Herein lies the problem: we are well into the promised Naya Pakistan. And to nobody's surprise, it appears that the nexus between government organs and big business has not gone anywhere. The world continues to do business as business was always done.

This should not be an excuse for continued wrongdoing under any government. But surely we might ask the ruling party and its vociferous talking heads: are they holding themselves to a separate standard from their political opponents?