The world of arts in South Asia was just coming to terms with the loss of one-half of the Bollywood music duo Wajid Khan to COVID-19 on May 31, and preparing to remember Pakistan’s great writer and intellectual Dr. Enver Sajjad on his first death anniversary on June 6, when I read the news of Dr. Asif Farrukhi’s passing away flashing on my Facebook newsfeed on June 1 last night. ‘Unbelievable!’ I said to myself, and immediately called up Kishwar Naheed in Islamabad, one of Farrukhi’s closest friends, collaborators and associates, her voice sobbing inconsolably, which was just as heartrending as the news itself; and confirmed what the mind did not want to believe.

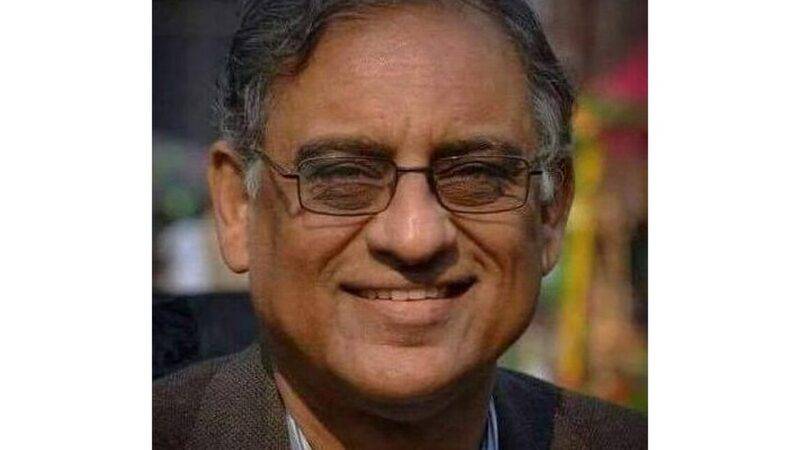

How could one believe the news of Farrukhi’s death, one had not even come to terms with his latest fortnightly essay for Dawn, published just the day before, a scintillating review of Afzal Ahmed Syed’s selected translation of Persian ghazals. Farrukhi was just 60. He had had a heart attack and he passed away in the hospital before he could receive medical help. He was a multi-faceted personality – a veritable all-rounder as we say in our South Asian cricketing parlance – and had matchless literary contributions in the fields of short-story writing and criticism, as well as translation.

Farrukhi was born in 1959 in Karachi to renowned writer and researcher Dr. Aslam Farrukhi, so an inclination towards literature was inherent to him. He was also related to renowned Urdu writers Deputy Nazeer Ahmed and Shahid Ahmed Dehlavi on his mother’s side. He got his initial education from St Patrick’s School and then did his Intermediate from D.J. Science College, and turned towards medicine. He had received the MBBS degree from Dow Medical College.

A passion for higher education took him to Harvard University in the United States where he did his Masters in Public Health. Then he did a short course in Health Economics from London and taught as Instructor at the Aga Khan University Hospital in Karachi. Prior to his untimely death, he was teaching at the Habib University in Karachi.

Apart from writing columns in English-language newspapers, he also conducted interviews. His book entitled Harf-e-Man-o-Tu (A Word Between Me and You) consisting of interviews of various personalities has been published. In addition he authored Aatish Fishan Par Khile Gulab (Roses Blooming Over a Volcano), Aalam-e-Eejaad (World of Invention), Cheezen Aur Log (Things and People), Cheezon Ki Kahanian (Stories of Things), Ism-e-Azam Ki Talaash (The Search for the Highest Name), Mere Din Guzar Rahe Hen (My Days Are Passing By), Shehr Beeti (Autobiography of A City), Shehr Maajra (The City Incident) and Men Shaakh Se Kyun Toota (Why I Severed from the Branch) and numerous books. His certainly definitive biography of Intizar Hussain Chiragh-i-Shab-i-Afsana (Light of the Night of the Short-Story) was well-received and will stand as an everlasting monument of Farrukhi’s love and labour for his subject.

He wrote more than sixty books which include six collections of short stories, two books of literary criticism, numerous translations, etc. but no novel, though he translated many novels. He also had a publishing house by the name of ‘Scheherazade’ and had been successfully publishing a respected literary journal Dunyazad for almost two decades before it ceased publication last year.

He was also the pioneer, together with Ameena Saiyid, of the Karachi Literature Festival (KLF), Pakistan’s first-ever literary festival in 2010 which ran for ten consecutive editions and later spread to Islamabad, and was mimicked with varying degrees of success in many other Pakistani cities. Since the last two years, he had been co-organizing the Adab Festival in Karachi.

My own introduction to his work began decades before I had met him in person or corresponded with him. I read and very much enjoyed his early translation of Italian writer Ignazio Silone’s anti-fascist epic Fontamara published by his publishing house. But I also wondered what Farrukhi would have made of later revelations of Silone’s participation in the CIA-funded anti-communist Congress for Cultural Freedom during the Cold War, and of his involvement as an informant for the Italian fascist police and later the American intelligence services, which came years after Farrukhi had translated the novel.

Then during my own stay in Karachi in the mid-2000s as a lowly State Bank functionary, I often heard and saw Farrukhi at the city’s various fora, including the Goethe Institute. For me, Karachi became inextricably synonymous with both Asif Farrukhi and Sabeen Mahmud, that other Karachi icon who too was cut down in her prime. It was also here that one heard in hushed tones of the presence of literary cliques which Farrukhi – among others – was part or wasn’t part of; one learnt in later years to discount such matters, whether because of inexperience or other priorities. When I returned to Lahore, I began an email correspondence with Farrukhi, and I will never forget how he was kind enough to send me his edited book Manto Ka Admi Nama (Manto’s Book of Man) published on the occasion of Manto’s birth centenary in 2012. It not only contained two extremely perceptive essays by the editor himself, but observations and reflections on Manto by some of my favourite writers like Fahmida Riaz, Asim Butt, Hameed Shahid, Saghir Ifrahim, Masood Ashar, Kamran Asdar Ali and Kishwar Naheed.

Farrukhi’s legendary reverence for the late Intizar Hussain was reflected here by the fact that he named the book after Hussain’s eponymous essay in the book itself. I suspect Farrukhi even named his publishing house after the title of one of Hussain’s short-stories Scheherzade Ki Maut (The Death of Scheherzade). I also began following Farrukhi’s weekly articles and book reviews which he began writing for Dawn in mid-2013. One would especially wait for his annual pontifications on the year’s most important literary prizes, namely the Booker and the Nobel, despite the fact that his disinclination towards Progressivism was well-known and it was possible to disagree with his views on topics like the literary merit of Krishan Chander’s partition stories and his own championing of a few select Urdu writers at the expense of others, especially at literary festivals like the KLF (I disagreed strongly with him on both). However whatever one’s own view, it was impossible to ignore Farrukhi’s musings from one literary genre to another.

I believe he drew deeply from the well-spring of two of his literary mentors: Muhammad Hasan Askari in literary criticism, and Intizar Hussain in short-story writing, both of whom were also closer to him in terms of his own literary ideology. Like Askari, Farrukhi had command over not only Urdu but world literature, something which was reflected in the quality of his translations, both from national and international languages; like Hussain, his stories were richly metaphorical.

However, unlike both Askari and Hussain, Farrukhi did not have the sort of parochial attitude towards the Progressive Writers Movement which marked Askari fairly early in his career leading to grotesque worship of obscurantism in his final years, and which with Hussain only began to change in his twilight years. In the last three to four years of Farrukhi’s life, I was privileged to run into him more often at one literary conference or festival or another in Lahore or Islamabad. In the spring of 2016, at a conference on ‘Urbanism, Exclusion and Social Change in South Asia’, organized by our friends Nida Kirmani and Ali Raza at LUMS in Lahore, I was lucky to share a panel on ‘Writing the City’ with Farrukhi, where he made an astonishing presentation on reading the politics of identity and accommodation in Intizar Hussain’s novel Naya Ghar (New House), which pushed me to seek out the novel on my own.

More recently, I attended Farrukhi’s keynote address on ‘A New Harvest of Anger: A case study of reading contemporary Urdu literature from Pakistan’ at an international conference on ‘Literature, Society and Prosperity’ organized by another friend Dr Sheeraz Dasti, at the International Islamic University in Islamabad last spring, where he shared his impressions based on his experiences of teaching various Urdu writers with his students at Habib University.

My last meeting with him was just a cursory one in February at this year’s Adab Festival in Karachi, where he was kind enough to invite me as a panelist for the launch of Rakhshanda Jalil’s meticulously curated collection Jallianwala Bagh, to which I had contributed a chapter; as well as allocating me to talk in an intriguing panel on ‘Peasants in Literature’. He graciously acknowledged my presence at the Festival. And that was that.

The mind now invariably wanders to one of Farrukhi’s final columns in Dawn dated May 10, titled A Time for Death. It seems eerie now that he could have written these lines:

‘With no drug available yet, a specific vaccine is a distant possibility, and the globally recommended lockdown to halt the dreaded Covid-19 fast turning into a meltdown as infection rates remain high, these are anxious days. Any news in the media strikes harder than before, as there is ample spare time to read in detail and probe further. News of death, especially if unrelated to the dreaded coronavirus, seems all the more dismal. Where newspaper accounts are lean on details, I follow up with a Google search.

All deaths diminish and deprive me one way or the other.’

It is astonishing to think that while the whole column proceeds to acknowledge the recent deaths of Bollywood icons Irrfan Khan and Rishi Kapoor, then the Irish poet Eavan Boland and finally the 24-year old Danish-Palestinian poet Yahya Hassan, Farrukhi had no time to give even a brief hint of acknowledging his own. May this column then be treated as a prescient death-note, a final masterpiece by the irrepressible Asif Farrukhi? We shall never know!

Yet even in death, Farrukhi chose wisely. One certainly cannot fault him for his lack of taste. For June 1 also marked the deaths of the great Progressive Urdu critic Khalilur Rahman Azmi and the legendary Progressive short-story writer Khwaja Ahmad Abbas; so he is certainly in good company. How would Farrukhi feel ensconced between two Progressives? Also perhaps he was in a hurry to join his great father whose death anniversary was to be on June 15, exactly two weeks later.

Farrukhi’s untimely death has deprived Urdu of a consummate all-rounder, who at least deserved to make a century before returning to the pavilion. It is our biggest literary loss since the passing away of the king of Urdu humour Mujtaba Hussain in Hyderabad just last week, and the death of Nisar Aziz Butt in Lahore in February this year. It also deprived the Indian subcontinent of a towering bridge and ambassador between India and Pakistan.

His work and his example inspired younger writers, both men and women, throughout the Indian subcontinent and beyond, and because he has left behind hundreds of his students as well as capable and energetic literary successors in the fields of short-story writing, criticism and translation like Rakhshanda Jalil, Snehal Shingavi, Harris Khalique, Mehr Afshan Farooqi, Raza Rumi, Nasir Abbas Nayyar and Humaira Ishfaq, I am almost sure that we will see his like again.

It also means that Asif Farrukhi is now free to join up and talk to his heart’s content with his beloved Hasan Askari, Intizar Hussain and Fahmida Riaz and compose his very own Admi Nama, unencumbered by any worldly considerations. May he take his writ and wit to heaven.

How could one believe the news of Farrukhi’s death, one had not even come to terms with his latest fortnightly essay for Dawn, published just the day before, a scintillating review of Afzal Ahmed Syed’s selected translation of Persian ghazals. Farrukhi was just 60. He had had a heart attack and he passed away in the hospital before he could receive medical help. He was a multi-faceted personality – a veritable all-rounder as we say in our South Asian cricketing parlance – and had matchless literary contributions in the fields of short-story writing and criticism, as well as translation.

Farrukhi was born in 1959 in Karachi to renowned writer and researcher Dr. Aslam Farrukhi, so an inclination towards literature was inherent to him. He was also related to renowned Urdu writers Deputy Nazeer Ahmed and Shahid Ahmed Dehlavi on his mother’s side. He got his initial education from St Patrick’s School and then did his Intermediate from D.J. Science College, and turned towards medicine. He had received the MBBS degree from Dow Medical College.

A passion for higher education took him to Harvard University in the United States where he did his Masters in Public Health. Then he did a short course in Health Economics from London and taught as Instructor at the Aga Khan University Hospital in Karachi. Prior to his untimely death, he was teaching at the Habib University in Karachi.

Apart from writing columns in English-language newspapers, he also conducted interviews. His book entitled Harf-e-Man-o-Tu (A Word Between Me and You) consisting of interviews of various personalities has been published. In addition he authored Aatish Fishan Par Khile Gulab (Roses Blooming Over a Volcano), Aalam-e-Eejaad (World of Invention), Cheezen Aur Log (Things and People), Cheezon Ki Kahanian (Stories of Things), Ism-e-Azam Ki Talaash (The Search for the Highest Name), Mere Din Guzar Rahe Hen (My Days Are Passing By), Shehr Beeti (Autobiography of A City), Shehr Maajra (The City Incident) and Men Shaakh Se Kyun Toota (Why I Severed from the Branch) and numerous books. His certainly definitive biography of Intizar Hussain Chiragh-i-Shab-i-Afsana (Light of the Night of the Short-Story) was well-received and will stand as an everlasting monument of Farrukhi’s love and labour for his subject.

He wrote more than sixty books which include six collections of short stories, two books of literary criticism, numerous translations, etc. but no novel, though he translated many novels. He also had a publishing house by the name of ‘Scheherazade’ and had been successfully publishing a respected literary journal Dunyazad for almost two decades before it ceased publication last year.

He was also the pioneer, together with Ameena Saiyid, of the Karachi Literature Festival (KLF), Pakistan’s first-ever literary festival in 2010 which ran for ten consecutive editions and later spread to Islamabad, and was mimicked with varying degrees of success in many other Pakistani cities. Since the last two years, he had been co-organizing the Adab Festival in Karachi.

My own introduction to his work began decades before I had met him in person or corresponded with him. I read and very much enjoyed his early translation of Italian writer Ignazio Silone’s anti-fascist epic Fontamara published by his publishing house. But I also wondered what Farrukhi would have made of later revelations of Silone’s participation in the CIA-funded anti-communist Congress for Cultural Freedom during the Cold War, and of his involvement as an informant for the Italian fascist police and later the American intelligence services, which came years after Farrukhi had translated the novel.

Then during my own stay in Karachi in the mid-2000s as a lowly State Bank functionary, I often heard and saw Farrukhi at the city’s various fora, including the Goethe Institute. For me, Karachi became inextricably synonymous with both Asif Farrukhi and Sabeen Mahmud, that other Karachi icon who too was cut down in her prime. It was also here that one heard in hushed tones of the presence of literary cliques which Farrukhi – among others – was part or wasn’t part of; one learnt in later years to discount such matters, whether because of inexperience or other priorities. When I returned to Lahore, I began an email correspondence with Farrukhi, and I will never forget how he was kind enough to send me his edited book Manto Ka Admi Nama (Manto’s Book of Man) published on the occasion of Manto’s birth centenary in 2012. It not only contained two extremely perceptive essays by the editor himself, but observations and reflections on Manto by some of my favourite writers like Fahmida Riaz, Asim Butt, Hameed Shahid, Saghir Ifrahim, Masood Ashar, Kamran Asdar Ali and Kishwar Naheed.

Farrukhi’s legendary reverence for the late Intizar Hussain was reflected here by the fact that he named the book after Hussain’s eponymous essay in the book itself. I suspect Farrukhi even named his publishing house after the title of one of Hussain’s short-stories Scheherzade Ki Maut (The Death of Scheherzade). I also began following Farrukhi’s weekly articles and book reviews which he began writing for Dawn in mid-2013. One would especially wait for his annual pontifications on the year’s most important literary prizes, namely the Booker and the Nobel, despite the fact that his disinclination towards Progressivism was well-known and it was possible to disagree with his views on topics like the literary merit of Krishan Chander’s partition stories and his own championing of a few select Urdu writers at the expense of others, especially at literary festivals like the KLF (I disagreed strongly with him on both). However whatever one’s own view, it was impossible to ignore Farrukhi’s musings from one literary genre to another.

I believe he drew deeply from the well-spring of two of his literary mentors: Muhammad Hasan Askari in literary criticism, and Intizar Hussain in short-story writing, both of whom were also closer to him in terms of his own literary ideology. Like Askari, Farrukhi had command over not only Urdu but world literature, something which was reflected in the quality of his translations, both from national and international languages; like Hussain, his stories were richly metaphorical.

However, unlike both Askari and Hussain, Farrukhi did not have the sort of parochial attitude towards the Progressive Writers Movement which marked Askari fairly early in his career leading to grotesque worship of obscurantism in his final years, and which with Hussain only began to change in his twilight years. In the last three to four years of Farrukhi’s life, I was privileged to run into him more often at one literary conference or festival or another in Lahore or Islamabad. In the spring of 2016, at a conference on ‘Urbanism, Exclusion and Social Change in South Asia’, organized by our friends Nida Kirmani and Ali Raza at LUMS in Lahore, I was lucky to share a panel on ‘Writing the City’ with Farrukhi, where he made an astonishing presentation on reading the politics of identity and accommodation in Intizar Hussain’s novel Naya Ghar (New House), which pushed me to seek out the novel on my own.

More recently, I attended Farrukhi’s keynote address on ‘A New Harvest of Anger: A case study of reading contemporary Urdu literature from Pakistan’ at an international conference on ‘Literature, Society and Prosperity’ organized by another friend Dr Sheeraz Dasti, at the International Islamic University in Islamabad last spring, where he shared his impressions based on his experiences of teaching various Urdu writers with his students at Habib University.

My last meeting with him was just a cursory one in February at this year’s Adab Festival in Karachi, where he was kind enough to invite me as a panelist for the launch of Rakhshanda Jalil’s meticulously curated collection Jallianwala Bagh, to which I had contributed a chapter; as well as allocating me to talk in an intriguing panel on ‘Peasants in Literature’. He graciously acknowledged my presence at the Festival. And that was that.

The mind now invariably wanders to one of Farrukhi’s final columns in Dawn dated May 10, titled A Time for Death. It seems eerie now that he could have written these lines:

‘With no drug available yet, a specific vaccine is a distant possibility, and the globally recommended lockdown to halt the dreaded Covid-19 fast turning into a meltdown as infection rates remain high, these are anxious days. Any news in the media strikes harder than before, as there is ample spare time to read in detail and probe further. News of death, especially if unrelated to the dreaded coronavirus, seems all the more dismal. Where newspaper accounts are lean on details, I follow up with a Google search.

All deaths diminish and deprive me one way or the other.’

It is astonishing to think that while the whole column proceeds to acknowledge the recent deaths of Bollywood icons Irrfan Khan and Rishi Kapoor, then the Irish poet Eavan Boland and finally the 24-year old Danish-Palestinian poet Yahya Hassan, Farrukhi had no time to give even a brief hint of acknowledging his own. May this column then be treated as a prescient death-note, a final masterpiece by the irrepressible Asif Farrukhi? We shall never know!

Yet even in death, Farrukhi chose wisely. One certainly cannot fault him for his lack of taste. For June 1 also marked the deaths of the great Progressive Urdu critic Khalilur Rahman Azmi and the legendary Progressive short-story writer Khwaja Ahmad Abbas; so he is certainly in good company. How would Farrukhi feel ensconced between two Progressives? Also perhaps he was in a hurry to join his great father whose death anniversary was to be on June 15, exactly two weeks later.

Farrukhi’s untimely death has deprived Urdu of a consummate all-rounder, who at least deserved to make a century before returning to the pavilion. It is our biggest literary loss since the passing away of the king of Urdu humour Mujtaba Hussain in Hyderabad just last week, and the death of Nisar Aziz Butt in Lahore in February this year. It also deprived the Indian subcontinent of a towering bridge and ambassador between India and Pakistan.

His work and his example inspired younger writers, both men and women, throughout the Indian subcontinent and beyond, and because he has left behind hundreds of his students as well as capable and energetic literary successors in the fields of short-story writing, criticism and translation like Rakhshanda Jalil, Snehal Shingavi, Harris Khalique, Mehr Afshan Farooqi, Raza Rumi, Nasir Abbas Nayyar and Humaira Ishfaq, I am almost sure that we will see his like again.

It also means that Asif Farrukhi is now free to join up and talk to his heart’s content with his beloved Hasan Askari, Intizar Hussain and Fahmida Riaz and compose his very own Admi Nama, unencumbered by any worldly considerations. May he take his writ and wit to heaven.