"Even though Islamic Socialism borrowed heavily from Muslim Modernism, it saw the latter as an entity that was enacted to deal with colonialism but needed a new dimension in the post-colonial setting", Nadeem F Paracha recounts the rise and fall of Islamic Socialism in the Muslim world.

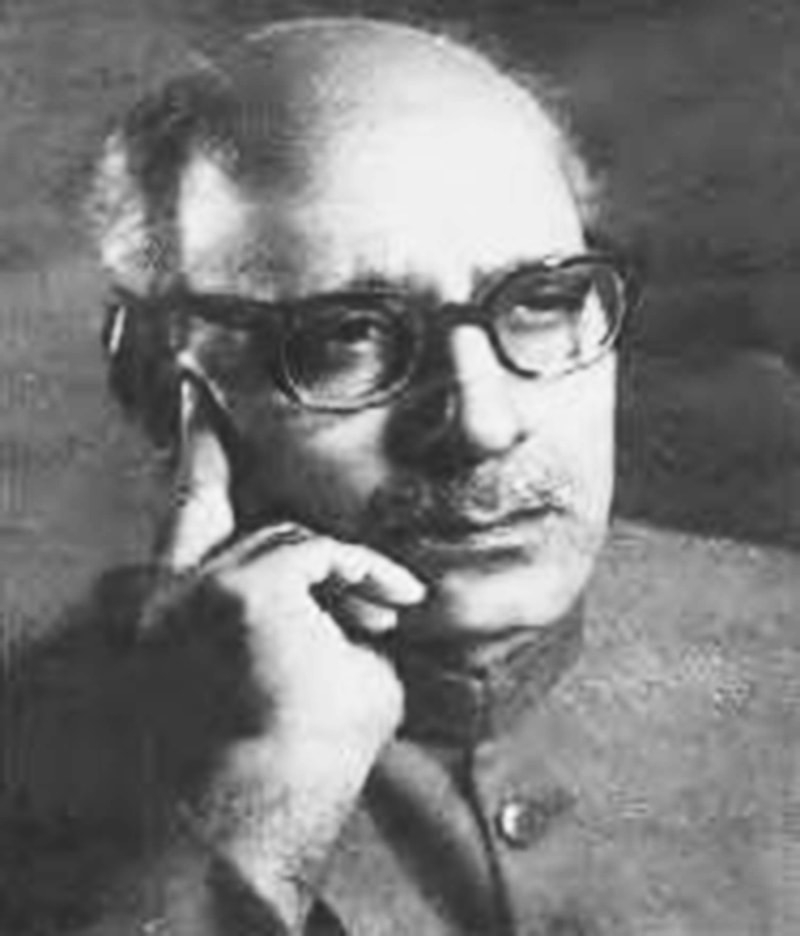

Islamic Socialism was an ideology that — from the 1940s till the 1970s — attracted the imagination and interest of a number of political ideologues in Muslim-majority regions. During this period, various variations of the ideology informed the economics and politics of dozens of Muslim-majority countries in Africa, the Middle East and Asia.

Like an idea or a set of ideas, Islamic Socialism had branched out from the concept of ‘Muslim Modernism’ which began to mushroom from the 19th century onwards as one of the many responses to the decline of Muslim imperial power and rise of European colonialism.

Muslim Modernism advocated the adoption of western education, a rational approach towards faith, and the modern sciences, because, according to the Muslim modernists, ‘Islam was inherently progressive and dynamic’ but had begun to stagnate due to the myopia of traditionalists[1]. This narrative held great traction for those looking to adjust to the realities of European colonialism.

Muslim modernists indulged in heated polemics with traditionalists and the more theologically-orientated Islamic reformers in Egypt, Iran, Turkey, Syria, Afghanistan, and India. They were often accused of draping secularism with a veil of Islam. The modernists responded by suggesting that Islam was already a modern faith and also secular because, unlike Christianity, there was no concept of an intermediary church/clergy in it.[2]

Various aspects of Muslim Modernism managed to influence a host nationalist movements among Muslims as they prepared to enter the post-colonial era in sovereign Muslim-majority countries. One prominent aspect in this context was Muslim Modernism’s appreciation of modern economic ideas such as free enterprise that in itself was an off-shoot of classic European mercantilism.

It was this and the triumph of the communist revolution in Russia which initiated the birth of the idea of Islamic Socialism from within sections of Muslim modernists.

As we can see, since Islamic Socialism was an off-shoot of Muslim Modernism, there were overlaps between the two. Even though Islamic Socialism borrowed heavily from Muslim Modernism, it saw the latter as an entity that was enacted to deal with colonialism but needed a new dimension in the post-colonial setting.

The fusion of Islam and socialism became that dimension offered in a more populist and assertive manner. But this ploy created its own complexities when states in this respect tried to navigate this fusion around engrained centres of social, political, and religious influences and interests. To counter these...

Part 1: Birth

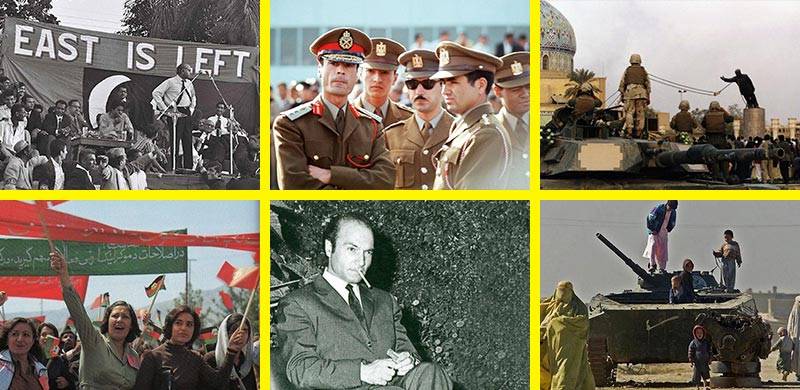

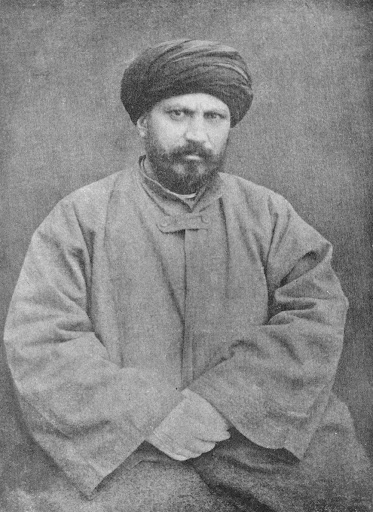

The 19th-century pan-Islamist and modernist, Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, was perhaps the first Muslim thinker and activist to study socialism and conclude that ‘socialism was an indigenous Arab doctrine located in pre-Islamic Arabian Bedouin traditions.’ He claimed that the framers of the initial Islamic state in the seventh century adopted these traditions as a structural basis from which to organize and regulate society. He is perhaps the first to have used the term Islamic Socialism which, to him, meant, ‘socialism based on love, reason, and freedom’ and not on the tyranny of materialism.[3]

In the late 19th century a Muslim reformist movement in Tatarstan, the Muslim-majority region of the Russian Empire, refused to follow the dictates of the Russian monarch. A decade later, the movement merged with a group of Muslim Modernists calling themselves the ‘jadeed.’ Consequently, after supporting leftist anti-monarchy Russian groups during a 1905 uprising, the movement took a left turn and its members began to call themselves Islamic Socialists.

The Tatar outfit was active in the 1917 Communist revolution. Its members fought alongside Vleldimer Lenin’s Bolsheviks in the civil war soon after the revolution. However, the alliance between the communists and the Tatar collapsed after Lenin’s demise and rise of Joseph Stalin. Whereas Lenin had allowed the Tatar to practice their faith (as long as they were willing to fight for the Bolsheviks and believed in socialism)[4] Stalin almost completely outlawed religion.

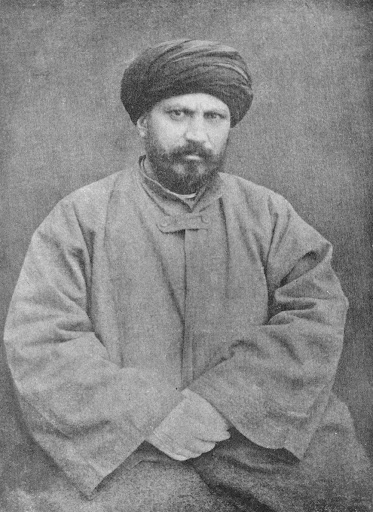

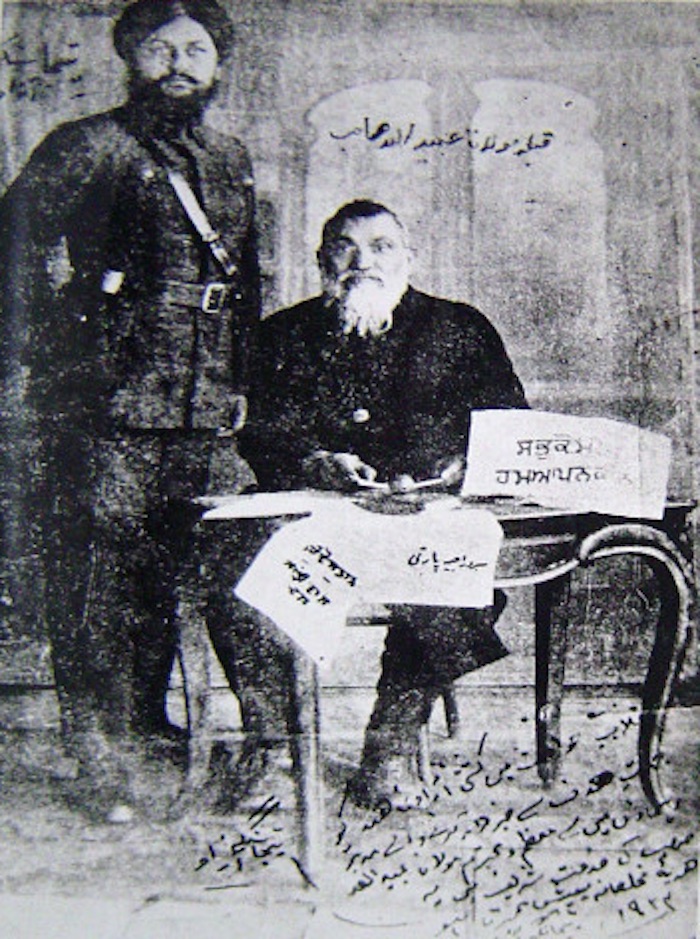

To escape arrest at the hands of the British, Indian Muslim thinker and agitator, Ubaidullah Sindhi (right) escaped to Kabul, and in 1922, arrived in Communist Russia. During his stay in Moscow, he keenly observed the principles of communism. When he reached Istanbul nine months later, he published a draft of a constitution for a ‘Free India’ in Urdu from Istanbul in 1924 which closely resembled the Soviet constitution in its economic character, emphasising peoples’ welfare, nationalisation, the abolition of feudalism and landlordism.

Ubaidullah understood socialist teachings to be directly in conformity with Islam.[5]

He urged Muslims ‘to evolve for themselves a religious basis to arrive at the economic justice at which communism aims but which it cannot fully achieve.’

The reason he gave for this was that though he saw both Islamic and Communist economic philosophies similar regarding their emphasis on the fair distribution of wealth, socialism, if imposed with the help of a more theistic and spiritual dimension, would be more beneficial to the peasant and the working classes than atheistic communism.

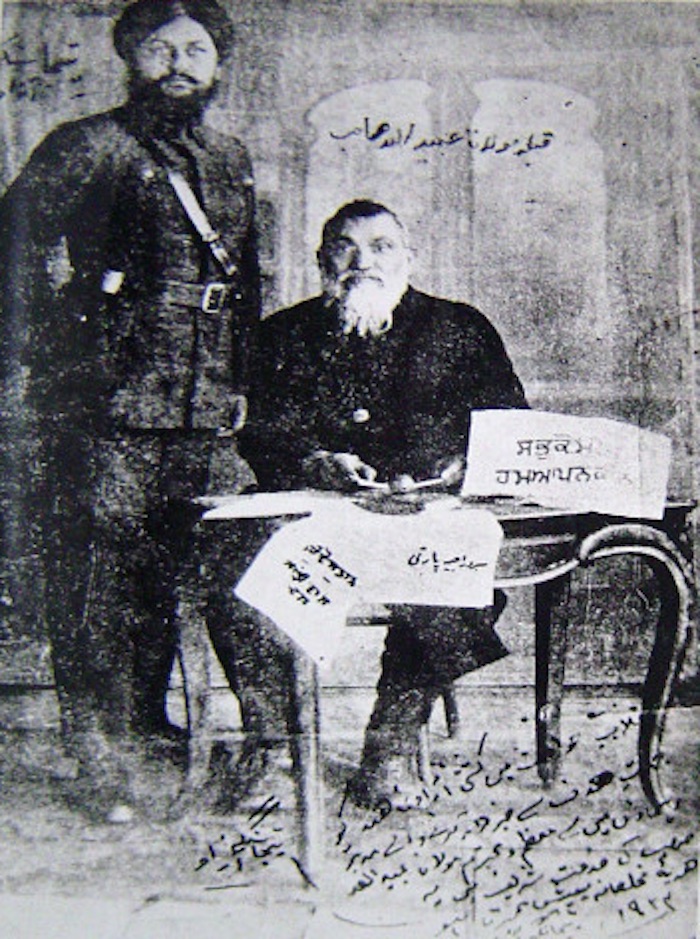

South Asian philosopher and poet, Muhammad Iqbal, who was one of the earliest advocates of a separate Muslim-majority state (future Pakistan) hailed the 1917 communist revolution in Russia. A great admirer of German thinkers from Hegel to Marx and Nietzsche, Iqbal desired an intellectual and spiritual upheaval among Muslims. According to him, the economic basis of socialism was identical to the teaching of the Quran. He believed that Islam and socialism had the same aim: to safeguard the sustenance of all the people.[6]

Iqbal believed that the best solution for the economic ills of all human communities has been put forward by Islam, which lacks in Karl Marx's theory of socialism. Marx sees religion as false consciousness. But to Iqbal, socialism devoid of any spiritual context was undesirable, something he believed Islam could add.

In 1922, the Indonesian philosopher and activist, Tan Malaka, made an impassioned speech during a visit to the Soviet Union which was backing his call to liberate Indonesia from Dutch colonialists. Malaka informed a large gathering of communists from around the world about ‘similarities between Pan-Islamism and Communism.’ Pan-Islamism was not religious per se, he argued, but rather ‘the brotherhood of all Muslim peoples, and the liberation struggle not only of the Arab but also of the Indian, the Javanese, and all the oppressed Muslim peoples.’

“This brotherhood,” he added, “means the practical liberation struggle not only against Dutch but also against English, French and Italian capitalism, therefore against world capitalism as a whole.”[7]

The Indian (and later Pakistani) Islamic scholar Ghulam Ahmad Parvez wrote a series of essays in the 1940s in which he claimed: The clergy and conservative ulema have hijacked Islam. They are agents of rich people and promoters of uncontrolled Capitalism. Socialism best enforces Quranic dictums on property, justice and distribution of wealth. That Islam’s main mission was the eradication of all injustices and cruelties from society and that according to the Quran, Muslims have three main responsibilities: seeing, hearing and sensing through the agency of the mind.

He stated that poverty was the punishment of God and deserved by those who ignore science. He insisted that a socialist path is a correction of the medieval distortion of Islam.

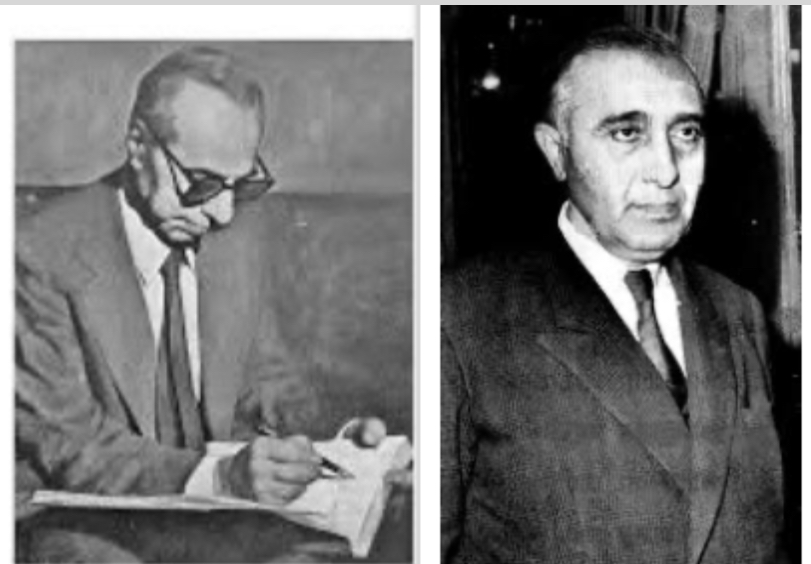

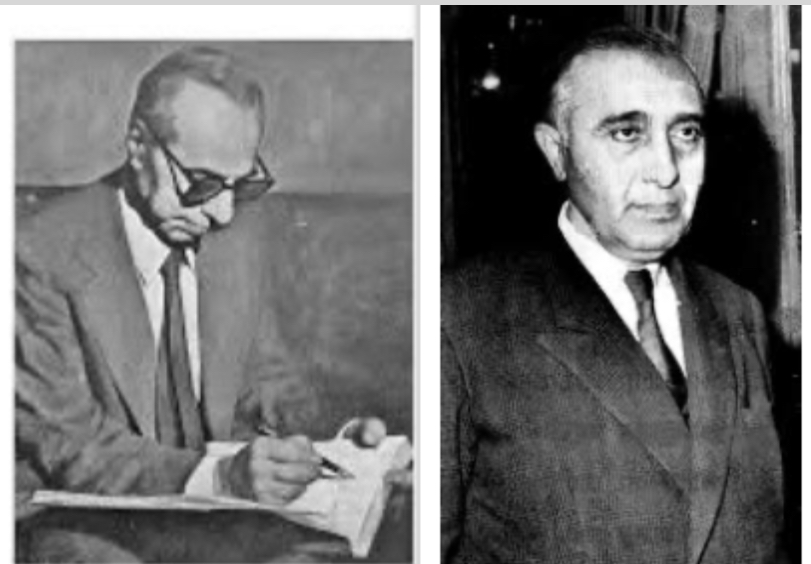

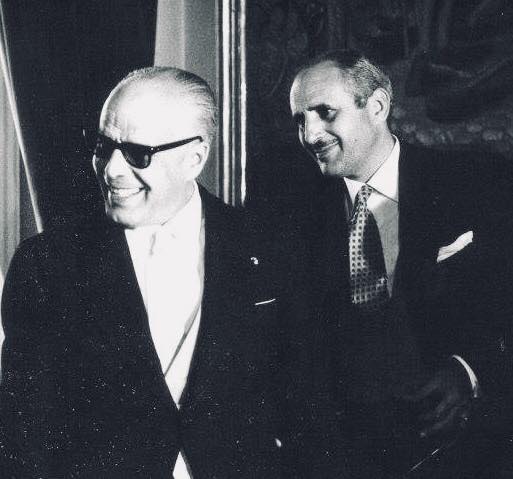

In the 1930s, two Syrian intellectuals, Michel Aflaq and Salah al-Din al-Bitar met in Paris to renovate Arab nationalism by infusing socialist economic ideas, a progressive cultural and social outlook, and reworking the idea of Islam inherent in it by evoking ‘Quran’s revolutionary spirit’ to counter injustice and inequality. They, however, advocated the separation of Islam (as an organised faith) from the matters of the state.

Aflaq and Bitar claimed that this would lead to a renaissance in the Arab world, turning it into an economic and political power. Both then formed the Arab Ba’ath Socialist Party or the Arab Renaissance Party.

In 1950, the Egyptian author and theologian, Khalid Muhammad Khalid, published a book, From Here We Begin in which he called for the separation of religion from state, as well as for democratic socialism, effective birth control and furtherance of the rights of women.[8]

Khalid was writing in an Egypt that was still being ruled by the British, and a British-backed monarch and in which the Muslim Brotherhood was agitating for the imposition of Shariah laws.

Khalid called for an independent Egypt that should adopt democratic socialism because it was already embedded in the teachings of Islam. However, he advocated the separation of religion and politics. Khalid’s ideas influenced the creation of what became to be known as ‘Arab Socialism.’

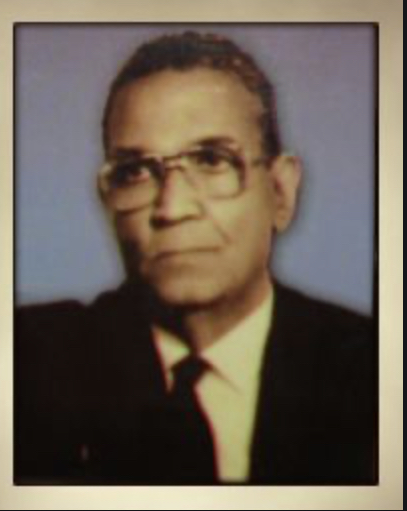

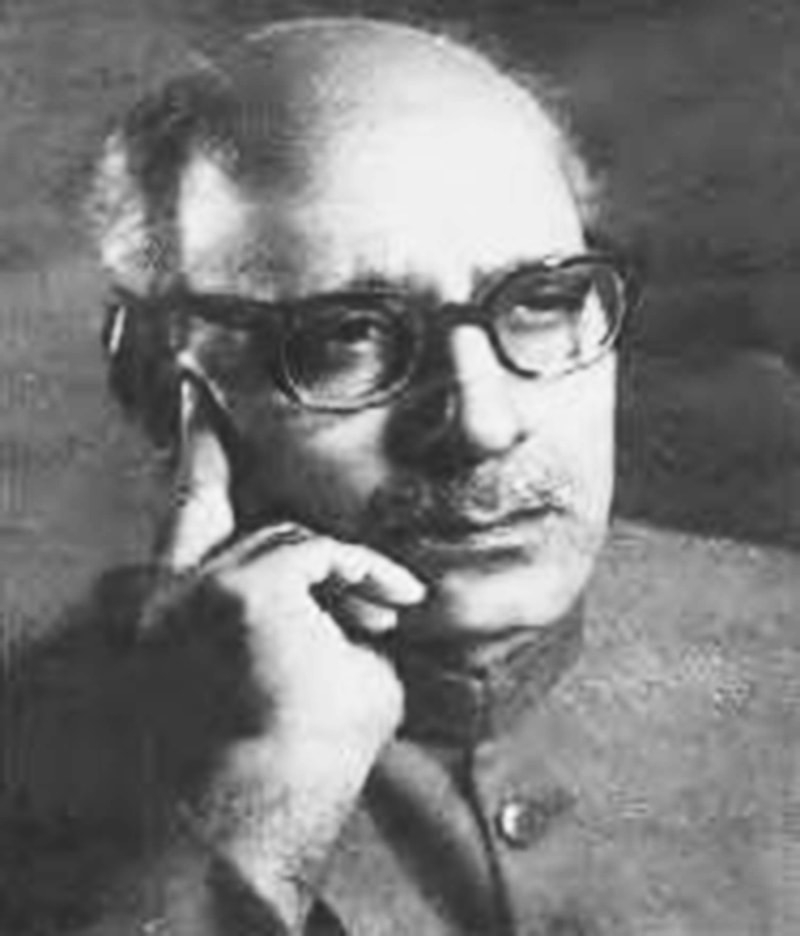

Poet, painter and author, Hanif Ramay, was one of the leading ideologues and theorists of Islamic Socialism in Pakistan. In the early and mid-1960s, he called for the elimination of feudalism, uncontrolled capitalism, and the encouragement of a system based on freedom of opportunity and/or an economic system closely monitored by the government and the state. He explained these demands as stemming from modern, 20th Century extensions of the principals of equality and justice as practiced by the first Muslim regime in Madina and Mecca, and of the many egalitarian economic and social proclamations found in the Holy Quran.

He denounced the conservative religious parties and the clergy for being representatives of monopolist capitalists, feudal lords, military dictators, the ‘imperialist forces of capitalism,’ and of being agents of backwardness and social and spiritual stagnation.[9] His ideas were adopted in 1967 by the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP).

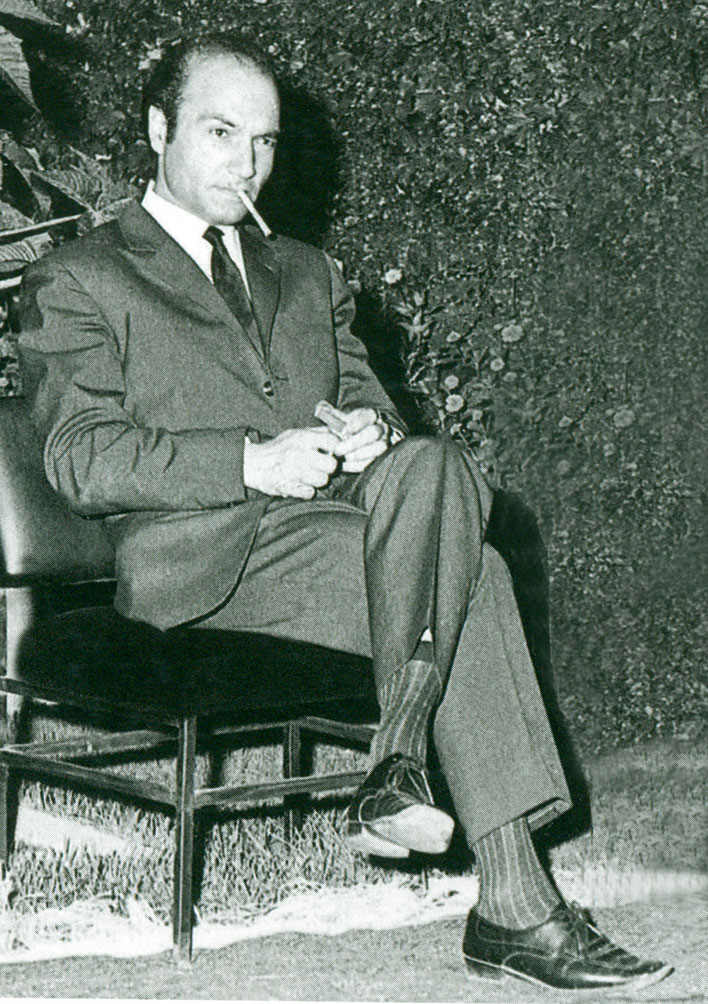

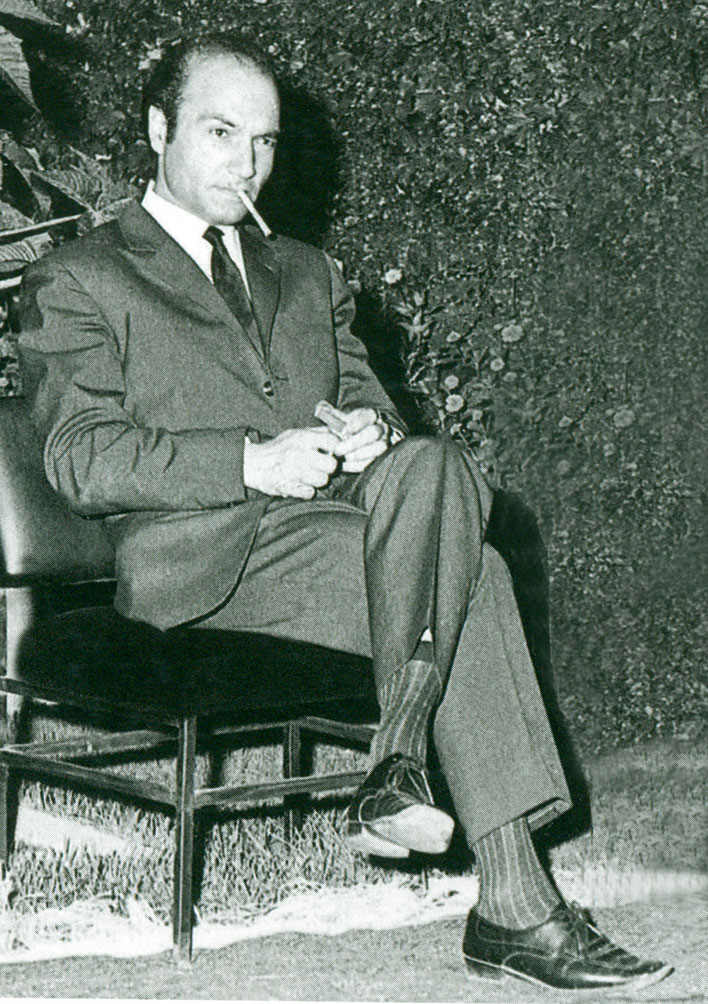

Dr. Ali Shariati was an Iranian sociologist who had studied in Paris and was jailed for his anti-Shah lectures and writings when he returned to Iran in 1964. He became popular among university and college students when he began to express revolutionary Marxist concepts through traditional Shia Muslim imagery and language. He died in 1977 in exile, allegedly poisoned by the agents of Shah’s regime.

Part 2: Triumph

In 1945, Indonesia gained independence from the Dutch. its first head of state, Kosno Sukarno, adopted many of Tan Malaka’s ideas by granting patronage to Indonesia’s communist party (the PKI) and Islamic Socialists inspired by Malaka. Sukarno defined the state doctrine through five principles (‘Pantjasila’): nationalism, internationalism, democracy, social prosperity, and belief in God — even though he ruled as a virtual dictator through what he called ‘guided democracy’ and ‘guided economy.’[10]

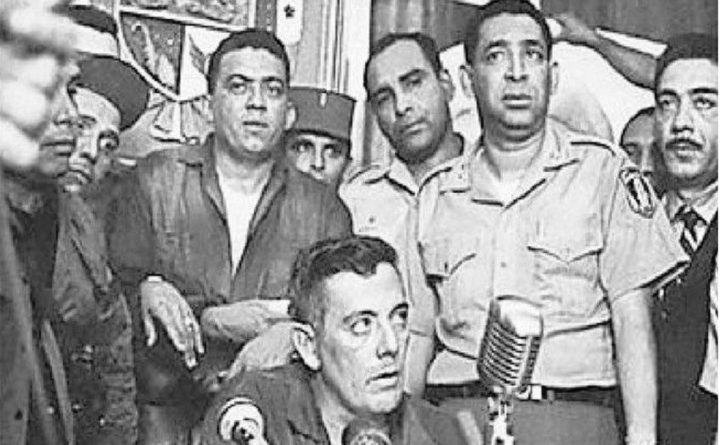

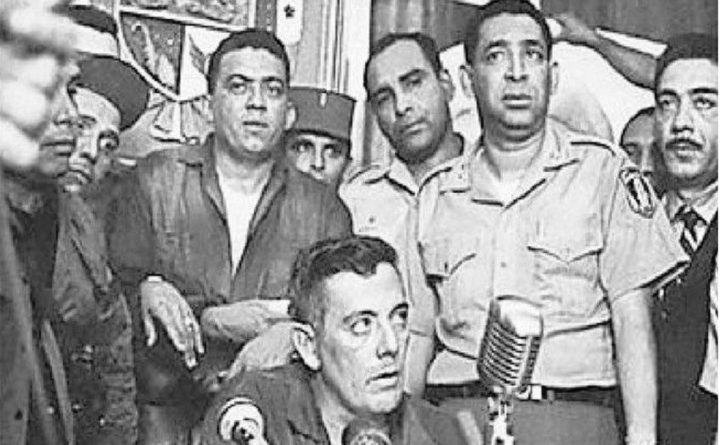

In 1952, a group of officers overthrew the Egyptian monarch and declared Egypt a republic. In 1954, one of the officers from the ruling junta, Gamal Nasser, rose to prominence and declared Egypt as an ‘Arab Socialist Republic.’ He began pushing Egypt in the Soviet camp after nationalising major sectors of the economy, including assets owned by the British and the US. He also banned the Muslim Brotherhood, saying, ‘Islam is best served when practiced in private.’

In 1957, after leading Tunisia towards independence, Habib Bourguiba put the country on path of his idea of Islamic Socialism. He argued that he wanted to adapt Islam to contemporary reality, and thereby returning to it its dynamic quality which stems from it being practiced in private and is not mixed with the affairs of the state.

A series of coups between 1961 and 1970 in Syria, strengthened the Syrian Ba’ath Socialist Party, establishing it as the country’s sole ruling party. Like Egypt, Syria too entered the Soviet camp.

In Algeria, during that country’s nationalist struggle against French colonialism that began to peak in the 1950s, the movement’s main outfit the Organisation Spéciale (Special Organisation) began to be drawn towards the ‘liberation philosophy’ of Arab/Ba’ath Socialism.

In 1954 The Special Organisation merged with various small left-wing nationalist groups and guerilla organisations to form the National Liberation Front (or the FLN – Front de Libération Nationale) that became the largest nationalist outfit during the Algerian liberation movement against French colonialists. Algeria won independence in 1962 and established a socialist state.

In 1967, Yemen’s National Liberation Front (NLF) managed to oust the British from the country. The NLF was inspired by Arab Socialism and backed by Nasser’s Egypt. Yemen was split into two with South Yemen becoming a socialist state whereas the north remained a pro-West monarchy sustained by Saudi Arabia.

In 1968, after a coup, the Iraq chapter of the Ba’ath Socialist Party consolidated its power in Baghdad. It became Iraq’s sole ruling party.

In 1969, a movement and then a coup led by Gaafar Nimeiry, a self-professed Arab Socialist and Nasser enthusiast, came to power in Sudan. Nimeiry announced his plan to base the country’s society, politics and economics on ‘independent Sudanese Socialism.’

The same year, in Somalia, Major General Mohamed Siad Barre pulled off a military coup. Barre at once rolled out a series of socialist economic policies and a literacy program. He then formed the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party and based its manifesto on ‘scientific socialism and the egalitarian tenants of Islam.’

In 1969, another admirer of Arab Socialism, Colonel Muammar Qadhafi, overthrew the Libyan monarch in a coup.

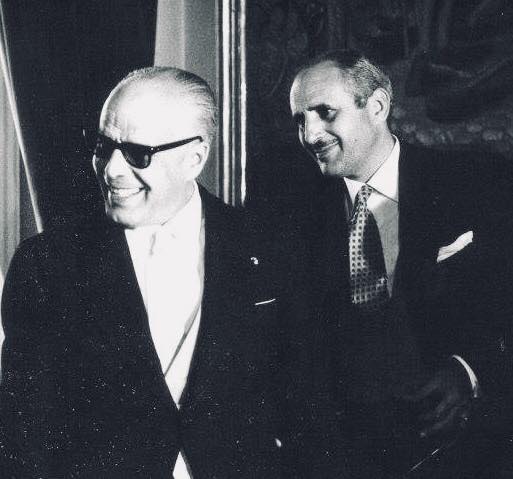

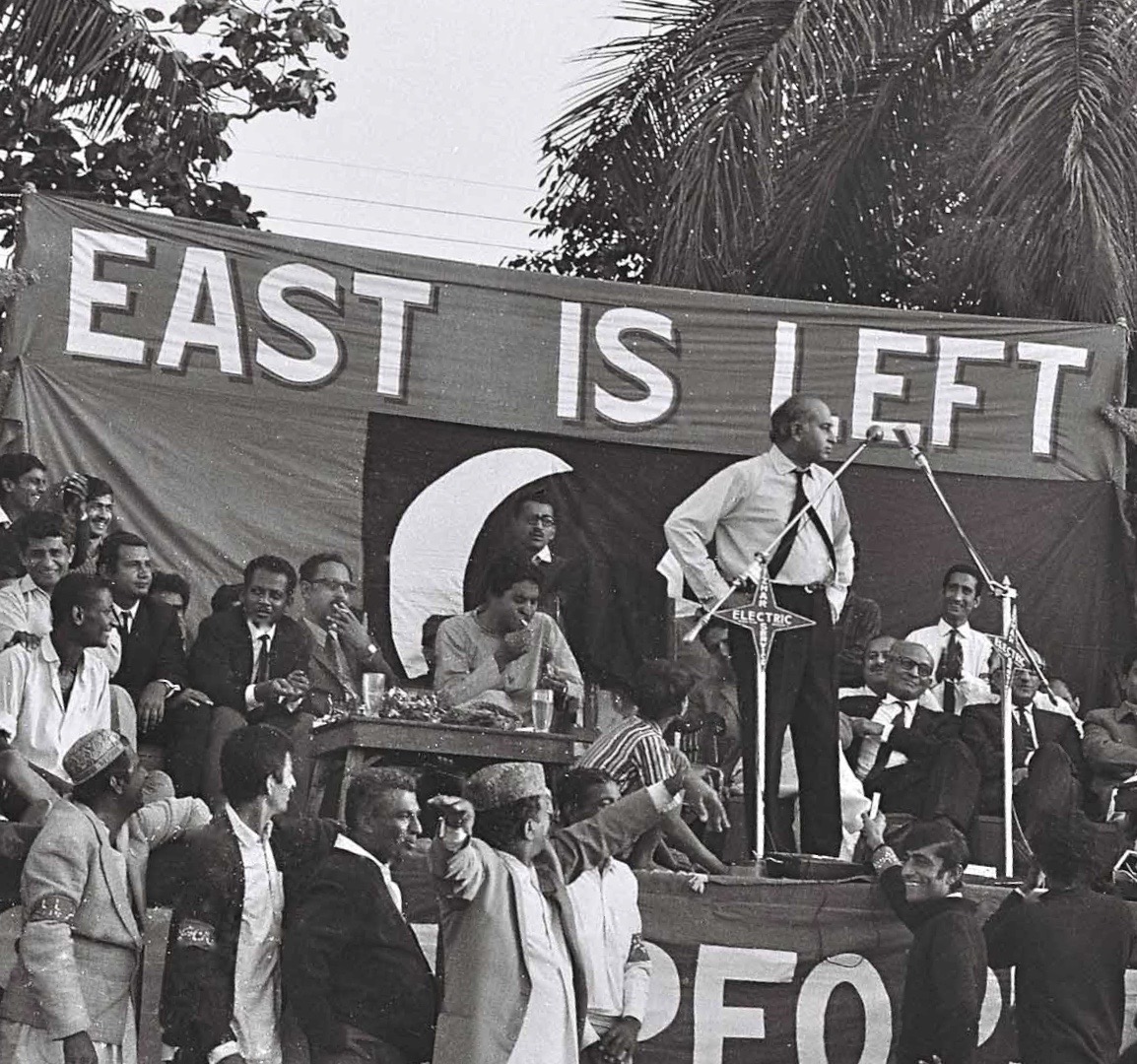

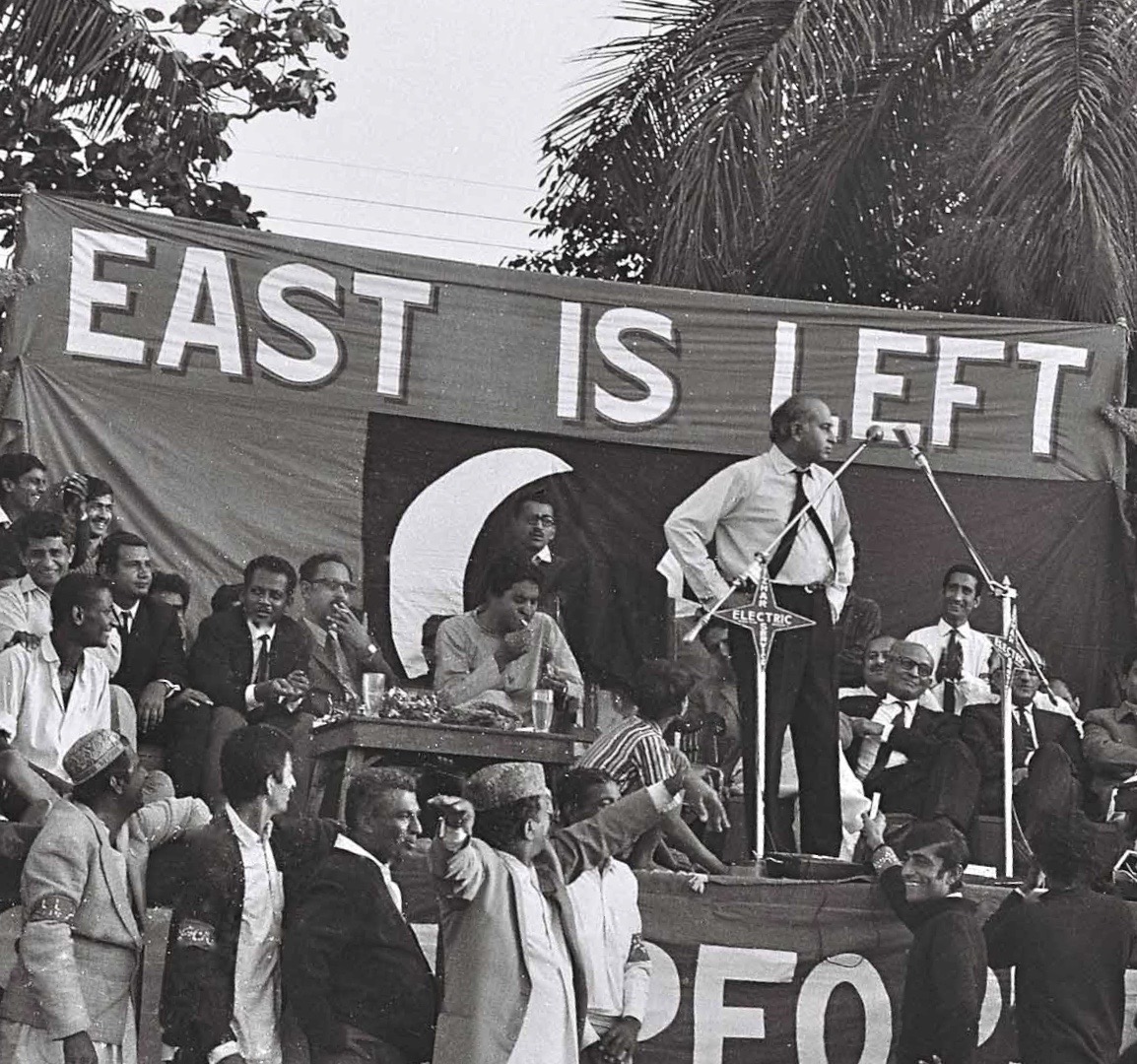

In December 1971, ZA Bhutto’s People’s Party came to power in Pakistan. The party promised to implement Islamic Socialism by ‘crushing feudalism, capitalism and religious conservatism.’

In 1978, communist factions in the Afghan military staged a coup. In the face of resistance and resentment from the Afghan clergy and landed elite in the country’s rural and semi-rural areas, the Soviet Union asked the new rulers to slow down its Marxist reforms. They then quickly began to shed their Marxist excesses and replaced them with the rhetoric being used at the time by Islamic Socialists and the Ba’ath Socialists.

Part 3: Demise

Indonesia: In 1965, Sukarno’s communist supporters (the PKI) became disillusioned by his slow pace of reform. They mobilised a pro-PKI faction in the military and attempted a coup. The coup was crushed by the pro-US faction of the military. It was followed by a brutal crackdown against the communists and their sympathisers by the military and Islamic parties. Thousands were slaughtered. Sukarno was also removed.

Egypt: Nasser lost much of his influence and clout when the Egyptian armed forces were routed by the Israeli army and air force in 1967. In 1970 he passed away. By 1974, his successor Anwar Sadat had already begun to rollback Nasser’s ‘socialist’ policies. He opened up the economy, lifted the ban on the Muslim Brotherhood, repaired ties with Saudi Arabia, and pulled Egypt out from the Soviet camp.

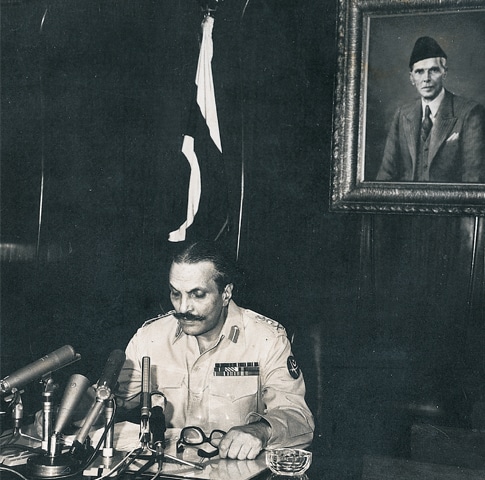

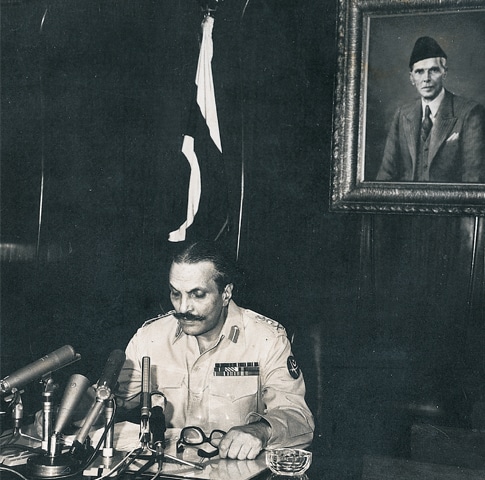

Pakistan: In 1977, the Bhutto regime was toppled in a reactionary military coup engineered by his own handpicked general, Zia-ul-Haq. In early 1977, the regime had faced a concentrated protest movement by an alliance of opposition parties demanding his resignation and imposition of shariah laws. Ironically, the regime itself had been shifting to the right since 1974 (like Sadat’s Egypt) but this could not stall its eventual fall.

Algeria: In the late 1980s, the FLN regime began to open up the country’s economy and engage with its Islamic opponents. In 1991 when Islamic groups won the first round of Algeria’s first-ever free parliamentary elections, the government nullified the results, plunging the country into a vicious civil war.

Somalia: In 1980, Siad Barre greatly rolled back his regime’s socialist reforms and accepted the US and Saudi aid after Somalia’s former ally the Soviet Union decided to support Ethiopia during the 1977 Somali-Ethiopia war.

Sudan: In 1981, Nimeiry, to neutralise Islamic opposition groups, agreed to reverse his socialist policies, denounce Islamic Socialism as a concoction and replace secular rule with an Islamic one. He then moved Sudan closer to the US and in 1981 announced a series of ‘Islamic laws.’

South Yemen: In 1990, when the Soviet Union was on the brink of disintegration and communism was in retreat, the socialist regime in South Yemen dissolved itself and joined with North Yemen to restore Yemen as a single country.

Afghanistan: With the withdrawal of Soviet forces from Afghanistan, the socialist regime in Kabul was left stranded to fight Islamic insurgents on its own. In 1989, the insurgents overwhelmed the last remnants of the regime.

Iraq: The Ba’ath regime in Iraq fell in 2004 after it was toppled by the invading US forces.

Libya: Gadhafi had already begun to distance his government from its ‘Islamic socialist’ past, but this could not stall his fall and murder by armed groups supported by western governments.

[1] M. Moaddel: Islamic Modernism, Nationalism, and Fundamentalism: Episode and Discourse (University of Chicago Press, 2005) p.2

[2] W. Lewis, H. Rollmann: Restoring the First-century Church in the Twenty-first Century (Wipf & Stock, 2005) p.388

[3] Afgani: Al-Radd ala al-Dahriyyin (Refutation of the Materialists), 1st edition, Beirut, 1886.

[4] What Killed the Promise of Muslim Communism? (New York Times, October 9, 2017).

[5] Ubaidullah, the Maulana Who Saw Socialism as Guarantor of Peoples' Welfare (The Wire, 21 August, 2018).

[6] IE. Sevea: The Political Philosophy of Muhammad Iqbal: Islam and Nationalism (Cambridge University Press, 2012) p.142

[7] New York Times op. cit.

[8] Islamic Socialism: GH. Grander; SA Hanna (The Muslim World, April 1966).

[9] Foundation Meeting Document No 4 of the Pakistan People‟s Party (Lahore: Masood Printers, 1967).

[10] The Development of Pancasila Moral Education in Indonesia: S. NISHIMURA (South Asian Studies, December 1995).

Islamic Socialism was an ideology that — from the 1940s till the 1970s — attracted the imagination and interest of a number of political ideologues in Muslim-majority regions. During this period, various variations of the ideology informed the economics and politics of dozens of Muslim-majority countries in Africa, the Middle East and Asia.

Like an idea or a set of ideas, Islamic Socialism had branched out from the concept of ‘Muslim Modernism’ which began to mushroom from the 19th century onwards as one of the many responses to the decline of Muslim imperial power and rise of European colonialism.

Muslim Modernism advocated the adoption of western education, a rational approach towards faith, and the modern sciences, because, according to the Muslim modernists, ‘Islam was inherently progressive and dynamic’ but had begun to stagnate due to the myopia of traditionalists[1]. This narrative held great traction for those looking to adjust to the realities of European colonialism.

Muslim modernists indulged in heated polemics with traditionalists and the more theologically-orientated Islamic reformers in Egypt, Iran, Turkey, Syria, Afghanistan, and India. They were often accused of draping secularism with a veil of Islam. The modernists responded by suggesting that Islam was already a modern faith and also secular because, unlike Christianity, there was no concept of an intermediary church/clergy in it.[2]

Various aspects of Muslim Modernism managed to influence a host nationalist movements among Muslims as they prepared to enter the post-colonial era in sovereign Muslim-majority countries. One prominent aspect in this context was Muslim Modernism’s appreciation of modern economic ideas such as free enterprise that in itself was an off-shoot of classic European mercantilism.

It was this and the triumph of the communist revolution in Russia which initiated the birth of the idea of Islamic Socialism from within sections of Muslim modernists.

- Variants of Islamic Socialism mobilised nationalist movements in Muslim countries caught between European colonialism, monarchism, and Islamic conservatism. It then offered a ‘third way’ between Western/American capitalism and Soviet communism.

- Like Muslim Modernism, it tried to wrestle away the right to interpret the socio-political aspects of Islam from the clergy and conservative ulema.

- It co-opted various Marxist, socialist and progressive strands and entities operating in Muslim countries and brought them all on a single platform.

- It tried to revive the idea of ‘Ijtihad’ (independent discussion on Islamic law and faith) that had been repressed in Muslim regions for centuries.

- It explained Islam as a progressive, dynamic, and rational faith.

- It eschewed differences in Muslim societies on the basis of clans, sects, and tribes.

- It creatively expressed economic and cultural policies with the help of progressive interpretations of Islamic texts and imagery.

- It added newer, more progressive dimensions to commentaries and the study of Islam and its place in society and politics.

- It encouraged the participation of women in the Muslim world in the economic, cultural, and political aspects of society.

- It emphasised the importance of having high literacy rates.

- It gave a political identity to middle-class youth and a sense of economic and ideological participation to the working classes۔

As we can see, since Islamic Socialism was an off-shoot of Muslim Modernism, there were overlaps between the two. Even though Islamic Socialism borrowed heavily from Muslim Modernism, it saw the latter as an entity that was enacted to deal with colonialism but needed a new dimension in the post-colonial setting.

The fusion of Islam and socialism became that dimension offered in a more populist and assertive manner. But this ploy created its own complexities when states in this respect tried to navigate this fusion around engrained centres of social, political, and religious influences and interests. To counter these...

- Islamic Socialist regimes remained autocratic and undemocratic in nature.

- In most regions, they heavily relied on the military.

- They exhibited extreme intolerance towards the opposition.

- In the Middle East, they were militaristic and yet failed over and over again in wars against foreign enemies.

- Their economic maneuvers remained largely half-baked and carelessly managed.

- Even though they rejected American hegemony and political influence in the name of independent economic and political existence, they banked on Soviet expertise, aid, and patronage.

- They violently repressed Islamic outfits but then turned supportively towards them when deciding to purge opposing leftist groups.

- This way they unwittingly revitalised Islamist and radical Islamic forces who eventually emerged to offer the ‘Islamic option’ with the collapse of Islamic Socialism.

Part 1: Birth

The 19th-century pan-Islamist and modernist, Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, was perhaps the first Muslim thinker and activist to study socialism and conclude that ‘socialism was an indigenous Arab doctrine located in pre-Islamic Arabian Bedouin traditions.’ He claimed that the framers of the initial Islamic state in the seventh century adopted these traditions as a structural basis from which to organize and regulate society. He is perhaps the first to have used the term Islamic Socialism which, to him, meant, ‘socialism based on love, reason, and freedom’ and not on the tyranny of materialism.[3]

In the late 19th century a Muslim reformist movement in Tatarstan, the Muslim-majority region of the Russian Empire, refused to follow the dictates of the Russian monarch. A decade later, the movement merged with a group of Muslim Modernists calling themselves the ‘jadeed.’ Consequently, after supporting leftist anti-monarchy Russian groups during a 1905 uprising, the movement took a left turn and its members began to call themselves Islamic Socialists.

The Tatar outfit was active in the 1917 Communist revolution. Its members fought alongside Vleldimer Lenin’s Bolsheviks in the civil war soon after the revolution. However, the alliance between the communists and the Tatar collapsed after Lenin’s demise and rise of Joseph Stalin. Whereas Lenin had allowed the Tatar to practice their faith (as long as they were willing to fight for the Bolsheviks and believed in socialism)[4] Stalin almost completely outlawed religion.

To escape arrest at the hands of the British, Indian Muslim thinker and agitator, Ubaidullah Sindhi (right) escaped to Kabul, and in 1922, arrived in Communist Russia. During his stay in Moscow, he keenly observed the principles of communism. When he reached Istanbul nine months later, he published a draft of a constitution for a ‘Free India’ in Urdu from Istanbul in 1924 which closely resembled the Soviet constitution in its economic character, emphasising peoples’ welfare, nationalisation, the abolition of feudalism and landlordism.

Ubaidullah understood socialist teachings to be directly in conformity with Islam.[5]

He urged Muslims ‘to evolve for themselves a religious basis to arrive at the economic justice at which communism aims but which it cannot fully achieve.’

The reason he gave for this was that though he saw both Islamic and Communist economic philosophies similar regarding their emphasis on the fair distribution of wealth, socialism, if imposed with the help of a more theistic and spiritual dimension, would be more beneficial to the peasant and the working classes than atheistic communism.

South Asian philosopher and poet, Muhammad Iqbal, who was one of the earliest advocates of a separate Muslim-majority state (future Pakistan) hailed the 1917 communist revolution in Russia. A great admirer of German thinkers from Hegel to Marx and Nietzsche, Iqbal desired an intellectual and spiritual upheaval among Muslims. According to him, the economic basis of socialism was identical to the teaching of the Quran. He believed that Islam and socialism had the same aim: to safeguard the sustenance of all the people.[6]

Iqbal believed that the best solution for the economic ills of all human communities has been put forward by Islam, which lacks in Karl Marx's theory of socialism. Marx sees religion as false consciousness. But to Iqbal, socialism devoid of any spiritual context was undesirable, something he believed Islam could add.

In 1922, the Indonesian philosopher and activist, Tan Malaka, made an impassioned speech during a visit to the Soviet Union which was backing his call to liberate Indonesia from Dutch colonialists. Malaka informed a large gathering of communists from around the world about ‘similarities between Pan-Islamism and Communism.’ Pan-Islamism was not religious per se, he argued, but rather ‘the brotherhood of all Muslim peoples, and the liberation struggle not only of the Arab but also of the Indian, the Javanese, and all the oppressed Muslim peoples.’

“This brotherhood,” he added, “means the practical liberation struggle not only against Dutch but also against English, French and Italian capitalism, therefore against world capitalism as a whole.”[7]

The Indian (and later Pakistani) Islamic scholar Ghulam Ahmad Parvez wrote a series of essays in the 1940s in which he claimed: The clergy and conservative ulema have hijacked Islam. They are agents of rich people and promoters of uncontrolled Capitalism. Socialism best enforces Quranic dictums on property, justice and distribution of wealth. That Islam’s main mission was the eradication of all injustices and cruelties from society and that according to the Quran, Muslims have three main responsibilities: seeing, hearing and sensing through the agency of the mind.

He stated that poverty was the punishment of God and deserved by those who ignore science. He insisted that a socialist path is a correction of the medieval distortion of Islam.

In the 1930s, two Syrian intellectuals, Michel Aflaq and Salah al-Din al-Bitar met in Paris to renovate Arab nationalism by infusing socialist economic ideas, a progressive cultural and social outlook, and reworking the idea of Islam inherent in it by evoking ‘Quran’s revolutionary spirit’ to counter injustice and inequality. They, however, advocated the separation of Islam (as an organised faith) from the matters of the state.

Aflaq and Bitar claimed that this would lead to a renaissance in the Arab world, turning it into an economic and political power. Both then formed the Arab Ba’ath Socialist Party or the Arab Renaissance Party.

In 1950, the Egyptian author and theologian, Khalid Muhammad Khalid, published a book, From Here We Begin in which he called for the separation of religion from state, as well as for democratic socialism, effective birth control and furtherance of the rights of women.[8]

Khalid was writing in an Egypt that was still being ruled by the British, and a British-backed monarch and in which the Muslim Brotherhood was agitating for the imposition of Shariah laws.

Khalid called for an independent Egypt that should adopt democratic socialism because it was already embedded in the teachings of Islam. However, he advocated the separation of religion and politics. Khalid’s ideas influenced the creation of what became to be known as ‘Arab Socialism.’

Poet, painter and author, Hanif Ramay, was one of the leading ideologues and theorists of Islamic Socialism in Pakistan. In the early and mid-1960s, he called for the elimination of feudalism, uncontrolled capitalism, and the encouragement of a system based on freedom of opportunity and/or an economic system closely monitored by the government and the state. He explained these demands as stemming from modern, 20th Century extensions of the principals of equality and justice as practiced by the first Muslim regime in Madina and Mecca, and of the many egalitarian economic and social proclamations found in the Holy Quran.

He denounced the conservative religious parties and the clergy for being representatives of monopolist capitalists, feudal lords, military dictators, the ‘imperialist forces of capitalism,’ and of being agents of backwardness and social and spiritual stagnation.[9] His ideas were adopted in 1967 by the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP).

Dr. Ali Shariati was an Iranian sociologist who had studied in Paris and was jailed for his anti-Shah lectures and writings when he returned to Iran in 1964. He became popular among university and college students when he began to express revolutionary Marxist concepts through traditional Shia Muslim imagery and language. He died in 1977 in exile, allegedly poisoned by the agents of Shah’s regime.

Part 2: Triumph

In 1945, Indonesia gained independence from the Dutch. its first head of state, Kosno Sukarno, adopted many of Tan Malaka’s ideas by granting patronage to Indonesia’s communist party (the PKI) and Islamic Socialists inspired by Malaka. Sukarno defined the state doctrine through five principles (‘Pantjasila’): nationalism, internationalism, democracy, social prosperity, and belief in God — even though he ruled as a virtual dictator through what he called ‘guided democracy’ and ‘guided economy.’[10]

In 1952, a group of officers overthrew the Egyptian monarch and declared Egypt a republic. In 1954, one of the officers from the ruling junta, Gamal Nasser, rose to prominence and declared Egypt as an ‘Arab Socialist Republic.’ He began pushing Egypt in the Soviet camp after nationalising major sectors of the economy, including assets owned by the British and the US. He also banned the Muslim Brotherhood, saying, ‘Islam is best served when practiced in private.’

In 1957, after leading Tunisia towards independence, Habib Bourguiba put the country on path of his idea of Islamic Socialism. He argued that he wanted to adapt Islam to contemporary reality, and thereby returning to it its dynamic quality which stems from it being practiced in private and is not mixed with the affairs of the state.

A series of coups between 1961 and 1970 in Syria, strengthened the Syrian Ba’ath Socialist Party, establishing it as the country’s sole ruling party. Like Egypt, Syria too entered the Soviet camp.

In Algeria, during that country’s nationalist struggle against French colonialism that began to peak in the 1950s, the movement’s main outfit the Organisation Spéciale (Special Organisation) began to be drawn towards the ‘liberation philosophy’ of Arab/Ba’ath Socialism.

In 1954 The Special Organisation merged with various small left-wing nationalist groups and guerilla organisations to form the National Liberation Front (or the FLN – Front de Libération Nationale) that became the largest nationalist outfit during the Algerian liberation movement against French colonialists. Algeria won independence in 1962 and established a socialist state.

In 1967, Yemen’s National Liberation Front (NLF) managed to oust the British from the country. The NLF was inspired by Arab Socialism and backed by Nasser’s Egypt. Yemen was split into two with South Yemen becoming a socialist state whereas the north remained a pro-West monarchy sustained by Saudi Arabia.

In 1968, after a coup, the Iraq chapter of the Ba’ath Socialist Party consolidated its power in Baghdad. It became Iraq’s sole ruling party.

In 1969, a movement and then a coup led by Gaafar Nimeiry, a self-professed Arab Socialist and Nasser enthusiast, came to power in Sudan. Nimeiry announced his plan to base the country’s society, politics and economics on ‘independent Sudanese Socialism.’

The same year, in Somalia, Major General Mohamed Siad Barre pulled off a military coup. Barre at once rolled out a series of socialist economic policies and a literacy program. He then formed the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party and based its manifesto on ‘scientific socialism and the egalitarian tenants of Islam.’

In 1969, another admirer of Arab Socialism, Colonel Muammar Qadhafi, overthrew the Libyan monarch in a coup.

In December 1971, ZA Bhutto’s People’s Party came to power in Pakistan. The party promised to implement Islamic Socialism by ‘crushing feudalism, capitalism and religious conservatism.’

In 1978, communist factions in the Afghan military staged a coup. In the face of resistance and resentment from the Afghan clergy and landed elite in the country’s rural and semi-rural areas, the Soviet Union asked the new rulers to slow down its Marxist reforms. They then quickly began to shed their Marxist excesses and replaced them with the rhetoric being used at the time by Islamic Socialists and the Ba’ath Socialists.

Part 3: Demise

Indonesia: In 1965, Sukarno’s communist supporters (the PKI) became disillusioned by his slow pace of reform. They mobilised a pro-PKI faction in the military and attempted a coup. The coup was crushed by the pro-US faction of the military. It was followed by a brutal crackdown against the communists and their sympathisers by the military and Islamic parties. Thousands were slaughtered. Sukarno was also removed.

Egypt: Nasser lost much of his influence and clout when the Egyptian armed forces were routed by the Israeli army and air force in 1967. In 1970 he passed away. By 1974, his successor Anwar Sadat had already begun to rollback Nasser’s ‘socialist’ policies. He opened up the economy, lifted the ban on the Muslim Brotherhood, repaired ties with Saudi Arabia, and pulled Egypt out from the Soviet camp.

Pakistan: In 1977, the Bhutto regime was toppled in a reactionary military coup engineered by his own handpicked general, Zia-ul-Haq. In early 1977, the regime had faced a concentrated protest movement by an alliance of opposition parties demanding his resignation and imposition of shariah laws. Ironically, the regime itself had been shifting to the right since 1974 (like Sadat’s Egypt) but this could not stall its eventual fall.

Algeria: In the late 1980s, the FLN regime began to open up the country’s economy and engage with its Islamic opponents. In 1991 when Islamic groups won the first round of Algeria’s first-ever free parliamentary elections, the government nullified the results, plunging the country into a vicious civil war.

Somalia: In 1980, Siad Barre greatly rolled back his regime’s socialist reforms and accepted the US and Saudi aid after Somalia’s former ally the Soviet Union decided to support Ethiopia during the 1977 Somali-Ethiopia war.

Sudan: In 1981, Nimeiry, to neutralise Islamic opposition groups, agreed to reverse his socialist policies, denounce Islamic Socialism as a concoction and replace secular rule with an Islamic one. He then moved Sudan closer to the US and in 1981 announced a series of ‘Islamic laws.’

South Yemen: In 1990, when the Soviet Union was on the brink of disintegration and communism was in retreat, the socialist regime in South Yemen dissolved itself and joined with North Yemen to restore Yemen as a single country.

Afghanistan: With the withdrawal of Soviet forces from Afghanistan, the socialist regime in Kabul was left stranded to fight Islamic insurgents on its own. In 1989, the insurgents overwhelmed the last remnants of the regime.

Iraq: The Ba’ath regime in Iraq fell in 2004 after it was toppled by the invading US forces.

Libya: Gadhafi had already begun to distance his government from its ‘Islamic socialist’ past, but this could not stall his fall and murder by armed groups supported by western governments.

[1] M. Moaddel: Islamic Modernism, Nationalism, and Fundamentalism: Episode and Discourse (University of Chicago Press, 2005) p.2

[2] W. Lewis, H. Rollmann: Restoring the First-century Church in the Twenty-first Century (Wipf & Stock, 2005) p.388

[3] Afgani: Al-Radd ala al-Dahriyyin (Refutation of the Materialists), 1st edition, Beirut, 1886.

[4] What Killed the Promise of Muslim Communism? (New York Times, October 9, 2017).

[5] Ubaidullah, the Maulana Who Saw Socialism as Guarantor of Peoples' Welfare (The Wire, 21 August, 2018).

[6] IE. Sevea: The Political Philosophy of Muhammad Iqbal: Islam and Nationalism (Cambridge University Press, 2012) p.142

[7] New York Times op. cit.

[8] Islamic Socialism: GH. Grander; SA Hanna (The Muslim World, April 1966).

[9] Foundation Meeting Document No 4 of the Pakistan People‟s Party (Lahore: Masood Printers, 1967).

[10] The Development of Pancasila Moral Education in Indonesia: S. NISHIMURA (South Asian Studies, December 1995).