By Nadeem Farooq Paracha

The term ‘Political Islam’ is an academic concoction. It works as an analytical umbrella under which political analysts and historians club together various political tendencies that claim to be using Muslim scriptures and historical traditions to achieve modern political goals.

The term first emerged in Europe soon after the First World War[1] to define anti-colonial movements that described themselves as Islamic in orientation. The term is a 20th century construct and its first prominent expression is believed to be Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, formed in 1927.

Political Islam covers a wide range of ideas and movements, emerging from within various Muslim sects, sub-sects and ethnic groups. These can be leftist as well as rightist in orientation.

From The Right

Islamic Fundamentalism

Islamic Fundamentalism is a vague term. It is largely associated with various radical and militant tendencies found in the Muslim world. But critics of this definition claim that it only means the observance of the fundamentals of Islam.

So, even though it is usually attributed to the beliefs of modern-day extremist movements in the Muslim world, Islamic Fundamentalism is basically a firm belief in the theological musings of classical Islamic jurists and the reported traditions and sayings of the faith’s leading luminaries.

Initially, the term was largely understood (in the West) as the Islamic equivalent of the 19th century Christian Fundamentalist Movement in the United States.[2] The movement believed in the literalist understanding of the Bible and was a reaction against modernism.

There is no clear consensus among historians on exactly when the term Islamic Fundamentalism began being associated with radical Islamic political movements. However, Western as well as Arab media had described the radical Egyptian Islamic activist and author, Sayyid Qutb, as an Islamic Fundamentalist when he was executed by the regime of Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1966.

More than a political doctrine, Islamic Fundamentalism is a theological tendency that is opposed to modernist/rationalist interpretations of Islam’s sacred scriptures. From the 12th century Islamic scholars who dealt an intellectual blow to the faith’s early rationalists (the Mu’tazilites) to present-day Islamic literalists and apolitical Islamic evangelicals, Islamic Fundamentalism has largely remained frozen in an understanding of the faith developed centuries ago by ancient Islamic scholars and jurists.

Even though many Islamic Fundamentalists are vocal about their rhetorical demands for the imposition of ‘Islamic laws’ (Sharia), Islamic Fundamentalism has little or no political agenda.

It remains largely associated with apolitical conservative ulema, the clergy and Islamic evangelists.

Early Manifestations: Ahmed Ibn Hanbal (9th century Arabian scholar and theologian); Sheikh Ahmed Sirhindi (16th Century Islamic scholar in Mughal India); Ibn Taymiyyah (12th/13th century Arabian theologian).

Cotemporary Manifestations: Tableeghi Jamat (Pakistan/India/Bangladesh/Indonesia); Farhat Hashmi/Al-Huda (Pakistan); Zakir Naik/Islamic Research Foundation (India); Dawat-e-Islami (Pakistan).

Neo-Islamic Fundamentalism

Term coined by acclaimed French expert on Political Islam, Oliver Roy,[3] in 1998. Neo-Islamic Fundamentalism is not only a reaction against modernity but also a critique of traditional Islamic Fundamentalism.

Like traditional Islamic Fundamentalism, Neo-Islamic Fundamentalism too is literalist in its understanding of Islamic scriptures. But unlike Islamic Fundamentalism, Neo-Islamic Fundamentalism looks to impose various modes of social morality and piety through force. Neo-Islamic Fundamentalists are known to have used coercion and mob violence to achieve this.

Therefore Neo-Islamic Fundamentalists are more likely than traditional Islamic Fundamentalists to use political means to achieve their social and theological goals.

Early Manifestations: The Kharijites (7th/8th century Arab puritans); Ibn Abd Al-Wahab (18th century Arabian theologian); the Ikhwan (early 20th century Saudi militia).

Contemporary Manifestations: Tehreek-e-Labaik Pakistan (Pakistan); The ‘religious/moral police’ Basji, Mutaween and Wilayatul Hisbah in Iran, Saudi Arabia and Indonesia; the Lal Masjid clerics (Pakistan).

Islamism

The term Islamism is derived from the 17th century German word, Islamismus, which, in the 18th century, was translated into English as ‘Islamism.’[4] Till the early 20th century it simply meant Islam.

However, when in the 1970s, the Muslim world at large began witnessing the emergence of various social and political Islamic movements, the term Islamism was revived by certain French academics studying these movements.

By the time of the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran and start of the Mujahedeen insurgency against the Soviet-backed government in Afghanistan in 1980, Islamism began to mean the political expression of Islamic theology.[5]

This understanding was largely based on the writings of Pakistani Islamic scholar, Abul Ala Maududi (d.1979) and the Egyptian activist Sayyid Qutb (d.1966) both of who had described the Qur’an to be the manifesto of their respective political organizations.

Founder of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, Hasan al-Banna (d.1949); Qutb; and Maududi interpreted the Qur’an and other Islamic texts through the prism of modern political concepts and lingo. For example, Maududi expanded the Qur’anic concept of Tauheed (oneness of God) by claiming that it also meant the (political) oneness of the Muslim ummah that can only be achieved through attaining state power and a universal ‘Islamic state’.

Qutb implied that 20th century Muslim societies were in a state of jahiliyya[6] – a term used by classical Muslim scholars to define the state of ignorance the people of Arabia were in before the arrival of Islam in the 7th century.

Qutb suggested that an armed jihad was required in Muslim countries to grab state power and rid the Muslims from the ‘modern forces of jahiliyya’ (which, to him, were secularism, Marxism, nationalism and ‘Western materialism’).[7]

So Islamism -- as it began to be understood from the early 1970s onwards -- vigorously eschewed ancient commentaries on Islamic scriptures and Sharia. It rejected these as being stuck in the mosque or undertaken to serve rulers who had divorced Islam from politics. Islamism claimed that Islam was as much a political doctrine as it was a moral and social guide.

Islamism in this context became the intellectual fodder which shaped various Islamic movements and even regimes between the 1960s and across the 1980s. These included the Muslim Brotherhood’s movement against Egypt’s Nasser regime in the 1960s; its activities against the Hafiz-ul-Asad’s regime in Syria (in the early 1980s); the anti-Bhutto movement in Pakistan by the Pakistan National Alliance (PNA) in early 1977; the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran; and the ‘Islamization programs’ of the Gen Zia dictatorship in Pakistan (1977-88); and the Islamization process in Sudan in the 1980s and 1990s; and the anti-Soviet Mujahedeen insurgency in Afghanistan in the 1980s.

Early Manifestations: The Jamiat Ulema Islam-Hind (India); The Khilafat Movement – 1919-24 (India); Hasan al-Bana (Egypt); Abul Aala Maududi (Pakistan); Sayyid Qutb (Egypt); Nahdlatul Ulema Party (Indonesia).

Contemporary Manifestations: Muslim Brotherhood (Middle East); Hasan al-Turabi (Sudan); Jamat-e-Islami (Pakistan/Bangladesh); Dr. Israr (Pakistan); Hamas (Palestine); Islamic Republic Party (Iran); National Islamic Front (Sudan); Justice and Development Party (Turkey); Enaadha Party (Tunisia).

Post-Islamism

The term post-Islamism is often explained as a process in which Islamism’s political and ideological tendencies mutated to become more militant and extreme in nature. Soon after the Afghan Civil War in the 1980s when various Mujahedeen groups splintered on ethnic and sectarian grounds, they did not disband.

Instead, believing that it was through their efforts that the Soviet Union had collapsed, many such groups internalized their movements by trying to trigger ‘Islamic uprisings’ in their own countries. They also turned against the United States, the country that had been one of the largest donors of money, training and weapons to the Mujahedeen in the 1980s.

Various internationalist and local militant Islamic outfits emerged across the Muslim world. Much of their tactics revolved around devising devastating terror attacks through indiscriminate bombings (including suicide bombings) not only against security and political targets but also against civilian populations.

The idea was to create social, economic and political chaos in Muslim societies and then exploit this chaos to install ‘Islamic regimes’ like the one the Taliban had set-up in Afghanistan between 1996 and 2001.

This line of thinking narrowed the whole idea of Islamism to mean extreme displays of religious and sectarian xenophobia and violence bordering on nihilism. Post-Islamism also devoid of the intellectual tradition associated with Islamism, settling instead for radical polemical literature which advocates violent action and an extremely narrow worldview.

Early Manifestations: First incarnation of Hezbollah (Lebanon); Islamic Jihad (Egypt); Al-Gamaat Al-Islamiyya (Egypt); Sipa-e-Sahaba (Pakistan); Sipa-e-Muhammad (Pakistan).

Contemporary Manifestations: Al-Qaeda (Global); Islamic State of Iraq and Levant/Daesh (Global); Armed Islamic Group (Algeria); Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (Pakistan); Boko Haram (Nigeria); Tehreek-i-Taliban (Pakistan); Taliban (Afghanistan); Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade (Palestine); Al-Shabab (Somalia); Jamma Islamiya (Indonesia).

Pan-Islamism

Pan-Islamism was a reaction against the 19th century consolidation of European colonialism. This idea, which propagated the formation of a centralized universal Islamic caliphate, was initially seeded by the Istanbul-based Ottoman caliph Abd Al-Hamid II.[8]

The leading intellectual proponent of early Pan-Islamism was Jamal al-din al-Afghani, a man of Persian decent. Afghani’s 19th century Pan-Islamism wanted to discard the political and intellectual lethargy that had crept in the Muslims’ way of thinking so that a more intellectually robust and politically modern universal Muslim polity could be built that was then able to challenge European imperialism and erect a universal Islamic caliphate.

Even though Afghani’s ideas did get some traction, by the late 19th century they largely faded away. However, these ideas returned to the fore with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the end of the First World War in 1919.

But by then Pan-Islamist ideas were largely adopted by radical Islamic outfits and individuals who eschewed Afghani’s modernist dimensions of Pan-Islamism and replaced them with more theological tendencies.

During the tussle between Egypt and Saudi Arabia between the 1950s and 1960s over the issue of which Arab country was to exercise more influence in the Muslim world, Saudi Arabia adopted a Pan-Islamist line to overcome the growth of Arab Nationalism and Islamic Socialism.

Pan-Islamism in the 1960s and 1970s meant the acquisition of western technologies and also the creation (rather, concoction) of ‘Islamic’ economics and even sciences largely financed by the Saudi monarchy and proliferated across the Muslim world.

This idea of Pan-Islamism began to flounder with the rise of Neo-Fundamentalism and Post-Islamism. It was however adopted by certain groups who retained the idea’s need to absorb academic and technological modernity, but intensified its anti-democracy tendencies.

From being a modernist intellectual tendency in the 19th century, to being a reactionary activist idea in the early 20th century, to becoming a Saudi-backed initiative between the 1960s and late 1980s, Pan-Islamism became a clandestine maneuver which wanted to infiltrate the militaries and intelligentsias in the Muslim world as a way to enact a new Muslim world order.

Early Manifestations: Jamal al-din al-Afghani; Maulana Abul Kalam Azad; Khilafat Movement (India, 1919-1924); Ubaidullah Sindhi; Abul Ala Maududi; Muslim Brotherhood.

Contemporary manifestations: Hizbut Tharir (Global); Islamic Salvation Front (Algeria).

_____________________

From The Left

Islamic Modernism

Islamic Modernism is a broad-based term. Its ideological core is fluid and can shift both ways, to the left or the right. Yet, historically, it has always felt the most comfortable sitting at the centre.

Islamic Modernism is a 19th century construct. More than a reaction, it emerged as a measured and pragmatic response to the rise of European colonialism and the political, social and economic modernity which accompanied this rise.

The term Islamic Modernism was probably first used in Russia. In the late 19th century a group of Muslim activists and intellectuals in Czarist Russia who wanted Russian Muslims to adopt European Enlightenment ideas began to call themselves the Jadeeds or the Modernists.[9]

The Jadeeds explained themselves to be progressive Muslims who were formulating an usus-ul-jadid or a modern methodology to reinvigorate Islam as a contemporary, living faith. Henceforth, many 19th century Muslim modernists elsewhere too began being known as jadeed Muslman.

The most politically and intellectually fertile years of Islamic Modernism were between the 19th and mid-20th centuries.

Islamic Modernism advocated a rational and contemporary interpretation of Islam’s sacred texts; the adoption of a scientific mindset; and the pragmatic absorption of social modernity. Islamic Modernists believed Islam to be a flexible and an inherently progressive and democratic faith.

The aim of Islamic Modernism was to make Muslim populations (who were disoriented by modernity) to embrace modern thinking and political institutions, and pragmatically adopt social modernity without compromising their Muslim identities.

Islamic Modernists also tried to contemporize Islam’s sacred texts and rationalize and express them in the context of modern political ideas such as democracy, capitalism and socialism; and of other more life-style-related aspects of modernity.

During the early and mid-20th century, Islamic Modernism shaped various powerful political movements, especially in Egypt, Turkey, Iran, Algeria, Tunisia and India/Pakistan. It began to decline as an idea from the late 1970s onwards, especially with the rise of Islamism and Saudi-backed Pan-Islamism.

Many historians and scholars perturbed by the rise of extremist ideas and consequent acts of violence in Muslim countries have begun to look back at Islamic Modernism to see if a contemporary and updated version of it could be revived.

Early Manifestations: The Mu’tazilites; Muhammad Abduh (Egypt); Rifa’a Al-Tahtwai (Egypt); Sir Syed Ahmad Khan (South Asia); Syed Ameer Ali (South Asia); Chiragh Ali (South Asia); Abdul Rauf Fitrat (Uzbekistan).

Contemporary Manifestations: Muhammad Iqbal (South Asia); Kamal Ataturk (Turkey); Muhammad Ali Jinnah (India/Pakistan); Ayub Khan (Pakistan); Dr. Fazal Rahman Malik (Pakistan); Dr. Khalifa Abdul Hakim (Pakistan); Ali Shariati (Iran); Farag Foda (Egypt); Habib Borguiba (Tunisia); Javed Ahmad Ghamidi (Pakistan).

Islamic Socialism

Islamic Socialism emerged as a branch of Islamic Modernism. Whereas Islamic Modernism had largely been sympathetic towards the idea of capitalism, a branch of it broke away after the 1917 communist revolution in Russia, to become known as Islamic Socialism.

Islamic Socialism attempted to equate Qur’anic concepts of equality and charity with modern Socialist economics. This idea when merged with active politics was aimed to trigger a cultural, intellectual and political renaissance in the Muslim world through whichever means necessary: revolution, the democratic process or through a military coup.

Islamic Socialism was also anti-clerical, socially liberal and mostly sympathetic towards communist powers, the Soviet Union and China. But it was not secular, as such. Islam was an important aspect of the idea. However, ideologues who shaped Islamic Socialism saw the ulema and clerics as agents of backwardness and exploitation. They insisted that there was no room for a theocracy in Islamic Socialism.

Islamic Socialism was a powerful populist idea in various Muslim countries from the 1930s till the early 1970s, before fading away.

Early Manifestations: The Waisi Movement (Soviet Union); Ubaidullah Sindhi (India); Ghulam Ahmad Parvez (India/Pakistan); Tan Malaka (Indonasia).

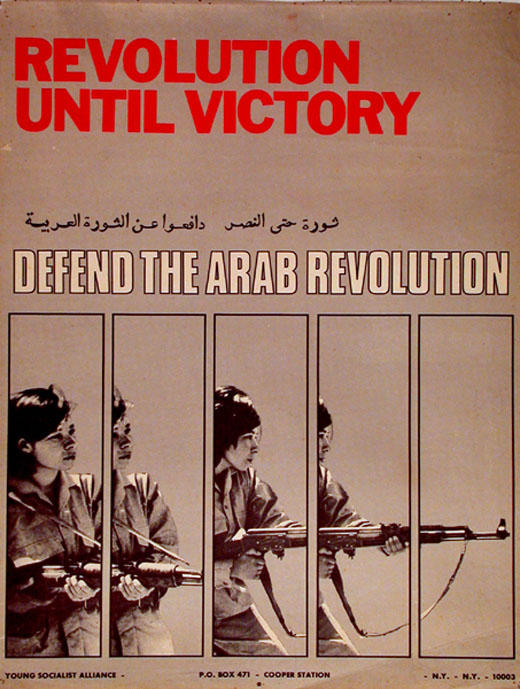

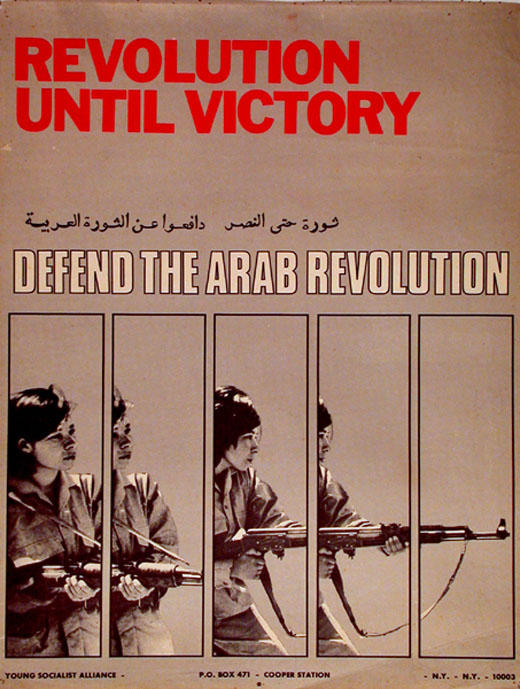

Contemporary Manifestations: Hanif Rammay (Pakistan); Pakistan People’s Party (Pakistan); Ali Shariati (Iran); Mujahideen-i-Khalq (Iran); Muammar Qaddafi (Libya); National Liberation Front (Algeria); Peoples Democratic Party (Afghanistan); Palestine Liberation Organization (Global).

Arab Socialism/Ba’ath Socialism

Arab Socialism and Ba’ath Socialism both evolved from Pan-Arabism or Arab Nationalism which began being formulated from the early 20th century as the Arab response to the rise of European colonialism. Both were also influenced by Islamic Socialism and Islamic Modernism.

In the Middle East, Islamic Socialism evolved into becoming a more nationalistic and revolutionary idea, mainly due to the creation of Israel (in 1948) and the expulsion of thousands of Palestinians from the area.

Syrian Arab nationalists, Michel Aflaq, Salah ad-Din Bitar are believed to be the originators of the Middle Eastern strain of Islamic Socialism that expressed itself as Arab Socialism and Ba’ath Socialism.

After studying the economic and political decline of the Arab peoples around the world, Aflaq and Bitar advocated the creation of a united Arab state.

For this they recast Arab nationalism by infusing into it a heavy dose of socialist economic ideas, progressive cultural and social outlook, and by reworking the idea of Islam inherent in it by evoking ‘Qur’an’s revolutionary spirit’ to counter injustice and inequality.

Aflaq and Bitar claimed that this would lead to a renaissance in the Arab world, turning it into an economic and political power.

Arab and Ba’ath Socialism appealed to the unity of all Arab nations on the basis of language/culture (Arab) and on the faith most Arabs followed (Islam).

They suggested that the Arab nations were being undermined by five forces: European colonialism (driven by capitalism); Soviet Communism; ‘decadent monarchies’ in Arab countries; Islamic conservatism; and the clergy who were keeping Arab societies in the clutches of backwardness.

Both the ideas offered a path between Western capitalism and Soviet communism by suggesting that all Arab nations come together as one state under a single ‘vanguard party’ of Arab nationalists who would impose socialist economic policies, modernize society through education, science and culture, separate religion from the state but continue being inspired by the egalitarian concepts of Islam.

In spite of being staunchly secular, Arab and Ba’ath Socialism celebrated Islam as proof of ‘Arab genius’, and a testament of Arab culture, values and thought.

Both the ideas flourished in the Middle East between the late 1940s and early 1970s, inspiring and enacting Arab Socialist regimes in Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Algeria, North Yemen, Sudan and Somalia before receding from the early 1970s onwards.

Early Manifestations: Michel Aflaq & Salah ad-Din Bitar (Syria); Gammal Abdel Nasser (Egypt).

Contemporary Manifestations: Arab Socialist Party (Egypt); Syrian Ba’ath Socialist Party (Syria); Iraq Ba’ath Socialist Party (Iraq); National Liberation Front (Algeria); National Liberation Front (Yemen); Muammar Qaddafi (Libya); Sudan Socialist Union (Sudan); Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (Somalia); PLO.

[1] Encyclopedia of Islam & Muslim World (Gale Globe, 2004)

[2] B Lewis: The Political Language of Islam (University of Chicago Press, 1988) p.117

[3] Oliver Roy: The Failure of Political Islam (Harvard University Press, 1998)

[4] Oxford English Dictionary (Oxford University Press, 2014)

[5] M Mozzafari: Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions (Routledge, 2007) p.18

[6] WE Shepard: Syed Qutb’s Doctrine of Jahiliyya, International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies (Novemeber 2003) p.521

[7] Ibid. p.545

[8] Aziz Ahmad: Islamic Modernism in India and Pakistan (Oxford University Press, 1967) p.124.

[9] A. Khalid: Jadidism in Central Asia (University of California Press, 1998) p.204

The term ‘Political Islam’ is an academic concoction. It works as an analytical umbrella under which political analysts and historians club together various political tendencies that claim to be using Muslim scriptures and historical traditions to achieve modern political goals.

The term first emerged in Europe soon after the First World War[1] to define anti-colonial movements that described themselves as Islamic in orientation. The term is a 20th century construct and its first prominent expression is believed to be Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, formed in 1927.

Political Islam covers a wide range of ideas and movements, emerging from within various Muslim sects, sub-sects and ethnic groups. These can be leftist as well as rightist in orientation.

From The Right

Islamic Fundamentalism

Islamic Fundamentalism is a vague term. It is largely associated with various radical and militant tendencies found in the Muslim world. But critics of this definition claim that it only means the observance of the fundamentals of Islam.

So, even though it is usually attributed to the beliefs of modern-day extremist movements in the Muslim world, Islamic Fundamentalism is basically a firm belief in the theological musings of classical Islamic jurists and the reported traditions and sayings of the faith’s leading luminaries.

Initially, the term was largely understood (in the West) as the Islamic equivalent of the 19th century Christian Fundamentalist Movement in the United States.[2] The movement believed in the literalist understanding of the Bible and was a reaction against modernism.

There is no clear consensus among historians on exactly when the term Islamic Fundamentalism began being associated with radical Islamic political movements. However, Western as well as Arab media had described the radical Egyptian Islamic activist and author, Sayyid Qutb, as an Islamic Fundamentalist when he was executed by the regime of Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1966.

More than a political doctrine, Islamic Fundamentalism is a theological tendency that is opposed to modernist/rationalist interpretations of Islam’s sacred scriptures. From the 12th century Islamic scholars who dealt an intellectual blow to the faith’s early rationalists (the Mu’tazilites) to present-day Islamic literalists and apolitical Islamic evangelicals, Islamic Fundamentalism has largely remained frozen in an understanding of the faith developed centuries ago by ancient Islamic scholars and jurists.

Even though many Islamic Fundamentalists are vocal about their rhetorical demands for the imposition of ‘Islamic laws’ (Sharia), Islamic Fundamentalism has little or no political agenda.

It remains largely associated with apolitical conservative ulema, the clergy and Islamic evangelists.

Early Manifestations: Ahmed Ibn Hanbal (9th century Arabian scholar and theologian); Sheikh Ahmed Sirhindi (16th Century Islamic scholar in Mughal India); Ibn Taymiyyah (12th/13th century Arabian theologian).

Cotemporary Manifestations: Tableeghi Jamat (Pakistan/India/Bangladesh/Indonesia); Farhat Hashmi/Al-Huda (Pakistan); Zakir Naik/Islamic Research Foundation (India); Dawat-e-Islami (Pakistan).

Neo-Islamic Fundamentalism

Term coined by acclaimed French expert on Political Islam, Oliver Roy,[3] in 1998. Neo-Islamic Fundamentalism is not only a reaction against modernity but also a critique of traditional Islamic Fundamentalism.

Like traditional Islamic Fundamentalism, Neo-Islamic Fundamentalism too is literalist in its understanding of Islamic scriptures. But unlike Islamic Fundamentalism, Neo-Islamic Fundamentalism looks to impose various modes of social morality and piety through force. Neo-Islamic Fundamentalists are known to have used coercion and mob violence to achieve this.

Therefore Neo-Islamic Fundamentalists are more likely than traditional Islamic Fundamentalists to use political means to achieve their social and theological goals.

Early Manifestations: The Kharijites (7th/8th century Arab puritans); Ibn Abd Al-Wahab (18th century Arabian theologian); the Ikhwan (early 20th century Saudi militia).

Contemporary Manifestations: Tehreek-e-Labaik Pakistan (Pakistan); The ‘religious/moral police’ Basji, Mutaween and Wilayatul Hisbah in Iran, Saudi Arabia and Indonesia; the Lal Masjid clerics (Pakistan).

Islamism

The term Islamism is derived from the 17th century German word, Islamismus, which, in the 18th century, was translated into English as ‘Islamism.’[4] Till the early 20th century it simply meant Islam.

However, when in the 1970s, the Muslim world at large began witnessing the emergence of various social and political Islamic movements, the term Islamism was revived by certain French academics studying these movements.

By the time of the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran and start of the Mujahedeen insurgency against the Soviet-backed government in Afghanistan in 1980, Islamism began to mean the political expression of Islamic theology.[5]

This understanding was largely based on the writings of Pakistani Islamic scholar, Abul Ala Maududi (d.1979) and the Egyptian activist Sayyid Qutb (d.1966) both of who had described the Qur’an to be the manifesto of their respective political organizations.

Founder of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, Hasan al-Banna (d.1949); Qutb; and Maududi interpreted the Qur’an and other Islamic texts through the prism of modern political concepts and lingo. For example, Maududi expanded the Qur’anic concept of Tauheed (oneness of God) by claiming that it also meant the (political) oneness of the Muslim ummah that can only be achieved through attaining state power and a universal ‘Islamic state’.

Qutb implied that 20th century Muslim societies were in a state of jahiliyya[6] – a term used by classical Muslim scholars to define the state of ignorance the people of Arabia were in before the arrival of Islam in the 7th century.

Qutb suggested that an armed jihad was required in Muslim countries to grab state power and rid the Muslims from the ‘modern forces of jahiliyya’ (which, to him, were secularism, Marxism, nationalism and ‘Western materialism’).[7]

So Islamism -- as it began to be understood from the early 1970s onwards -- vigorously eschewed ancient commentaries on Islamic scriptures and Sharia. It rejected these as being stuck in the mosque or undertaken to serve rulers who had divorced Islam from politics. Islamism claimed that Islam was as much a political doctrine as it was a moral and social guide.

Islamism in this context became the intellectual fodder which shaped various Islamic movements and even regimes between the 1960s and across the 1980s. These included the Muslim Brotherhood’s movement against Egypt’s Nasser regime in the 1960s; its activities against the Hafiz-ul-Asad’s regime in Syria (in the early 1980s); the anti-Bhutto movement in Pakistan by the Pakistan National Alliance (PNA) in early 1977; the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran; and the ‘Islamization programs’ of the Gen Zia dictatorship in Pakistan (1977-88); and the Islamization process in Sudan in the 1980s and 1990s; and the anti-Soviet Mujahedeen insurgency in Afghanistan in the 1980s.

Early Manifestations: The Jamiat Ulema Islam-Hind (India); The Khilafat Movement – 1919-24 (India); Hasan al-Bana (Egypt); Abul Aala Maududi (Pakistan); Sayyid Qutb (Egypt); Nahdlatul Ulema Party (Indonesia).

Contemporary Manifestations: Muslim Brotherhood (Middle East); Hasan al-Turabi (Sudan); Jamat-e-Islami (Pakistan/Bangladesh); Dr. Israr (Pakistan); Hamas (Palestine); Islamic Republic Party (Iran); National Islamic Front (Sudan); Justice and Development Party (Turkey); Enaadha Party (Tunisia).

Post-Islamism

The term post-Islamism is often explained as a process in which Islamism’s political and ideological tendencies mutated to become more militant and extreme in nature. Soon after the Afghan Civil War in the 1980s when various Mujahedeen groups splintered on ethnic and sectarian grounds, they did not disband.

Instead, believing that it was through their efforts that the Soviet Union had collapsed, many such groups internalized their movements by trying to trigger ‘Islamic uprisings’ in their own countries. They also turned against the United States, the country that had been one of the largest donors of money, training and weapons to the Mujahedeen in the 1980s.

Various internationalist and local militant Islamic outfits emerged across the Muslim world. Much of their tactics revolved around devising devastating terror attacks through indiscriminate bombings (including suicide bombings) not only against security and political targets but also against civilian populations.

The idea was to create social, economic and political chaos in Muslim societies and then exploit this chaos to install ‘Islamic regimes’ like the one the Taliban had set-up in Afghanistan between 1996 and 2001.

This line of thinking narrowed the whole idea of Islamism to mean extreme displays of religious and sectarian xenophobia and violence bordering on nihilism. Post-Islamism also devoid of the intellectual tradition associated with Islamism, settling instead for radical polemical literature which advocates violent action and an extremely narrow worldview.

Early Manifestations: First incarnation of Hezbollah (Lebanon); Islamic Jihad (Egypt); Al-Gamaat Al-Islamiyya (Egypt); Sipa-e-Sahaba (Pakistan); Sipa-e-Muhammad (Pakistan).

Contemporary Manifestations: Al-Qaeda (Global); Islamic State of Iraq and Levant/Daesh (Global); Armed Islamic Group (Algeria); Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (Pakistan); Boko Haram (Nigeria); Tehreek-i-Taliban (Pakistan); Taliban (Afghanistan); Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade (Palestine); Al-Shabab (Somalia); Jamma Islamiya (Indonesia).

Pan-Islamism

Pan-Islamism was a reaction against the 19th century consolidation of European colonialism. This idea, which propagated the formation of a centralized universal Islamic caliphate, was initially seeded by the Istanbul-based Ottoman caliph Abd Al-Hamid II.[8]

The leading intellectual proponent of early Pan-Islamism was Jamal al-din al-Afghani, a man of Persian decent. Afghani’s 19th century Pan-Islamism wanted to discard the political and intellectual lethargy that had crept in the Muslims’ way of thinking so that a more intellectually robust and politically modern universal Muslim polity could be built that was then able to challenge European imperialism and erect a universal Islamic caliphate.

Even though Afghani’s ideas did get some traction, by the late 19th century they largely faded away. However, these ideas returned to the fore with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the end of the First World War in 1919.

But by then Pan-Islamist ideas were largely adopted by radical Islamic outfits and individuals who eschewed Afghani’s modernist dimensions of Pan-Islamism and replaced them with more theological tendencies.

During the tussle between Egypt and Saudi Arabia between the 1950s and 1960s over the issue of which Arab country was to exercise more influence in the Muslim world, Saudi Arabia adopted a Pan-Islamist line to overcome the growth of Arab Nationalism and Islamic Socialism.

Pan-Islamism in the 1960s and 1970s meant the acquisition of western technologies and also the creation (rather, concoction) of ‘Islamic’ economics and even sciences largely financed by the Saudi monarchy and proliferated across the Muslim world.

This idea of Pan-Islamism began to flounder with the rise of Neo-Fundamentalism and Post-Islamism. It was however adopted by certain groups who retained the idea’s need to absorb academic and technological modernity, but intensified its anti-democracy tendencies.

From being a modernist intellectual tendency in the 19th century, to being a reactionary activist idea in the early 20th century, to becoming a Saudi-backed initiative between the 1960s and late 1980s, Pan-Islamism became a clandestine maneuver which wanted to infiltrate the militaries and intelligentsias in the Muslim world as a way to enact a new Muslim world order.

Early Manifestations: Jamal al-din al-Afghani; Maulana Abul Kalam Azad; Khilafat Movement (India, 1919-1924); Ubaidullah Sindhi; Abul Ala Maududi; Muslim Brotherhood.

Contemporary manifestations: Hizbut Tharir (Global); Islamic Salvation Front (Algeria).

_____________________

From The Left

Islamic Modernism

Islamic Modernism is a broad-based term. Its ideological core is fluid and can shift both ways, to the left or the right. Yet, historically, it has always felt the most comfortable sitting at the centre.

Islamic Modernism is a 19th century construct. More than a reaction, it emerged as a measured and pragmatic response to the rise of European colonialism and the political, social and economic modernity which accompanied this rise.

The term Islamic Modernism was probably first used in Russia. In the late 19th century a group of Muslim activists and intellectuals in Czarist Russia who wanted Russian Muslims to adopt European Enlightenment ideas began to call themselves the Jadeeds or the Modernists.[9]

The Jadeeds explained themselves to be progressive Muslims who were formulating an usus-ul-jadid or a modern methodology to reinvigorate Islam as a contemporary, living faith. Henceforth, many 19th century Muslim modernists elsewhere too began being known as jadeed Muslman.

The most politically and intellectually fertile years of Islamic Modernism were between the 19th and mid-20th centuries.

Islamic Modernism advocated a rational and contemporary interpretation of Islam’s sacred texts; the adoption of a scientific mindset; and the pragmatic absorption of social modernity. Islamic Modernists believed Islam to be a flexible and an inherently progressive and democratic faith.

The aim of Islamic Modernism was to make Muslim populations (who were disoriented by modernity) to embrace modern thinking and political institutions, and pragmatically adopt social modernity without compromising their Muslim identities.

Islamic Modernists also tried to contemporize Islam’s sacred texts and rationalize and express them in the context of modern political ideas such as democracy, capitalism and socialism; and of other more life-style-related aspects of modernity.

During the early and mid-20th century, Islamic Modernism shaped various powerful political movements, especially in Egypt, Turkey, Iran, Algeria, Tunisia and India/Pakistan. It began to decline as an idea from the late 1970s onwards, especially with the rise of Islamism and Saudi-backed Pan-Islamism.

Many historians and scholars perturbed by the rise of extremist ideas and consequent acts of violence in Muslim countries have begun to look back at Islamic Modernism to see if a contemporary and updated version of it could be revived.

Early Manifestations: The Mu’tazilites; Muhammad Abduh (Egypt); Rifa’a Al-Tahtwai (Egypt); Sir Syed Ahmad Khan (South Asia); Syed Ameer Ali (South Asia); Chiragh Ali (South Asia); Abdul Rauf Fitrat (Uzbekistan).

Contemporary Manifestations: Muhammad Iqbal (South Asia); Kamal Ataturk (Turkey); Muhammad Ali Jinnah (India/Pakistan); Ayub Khan (Pakistan); Dr. Fazal Rahman Malik (Pakistan); Dr. Khalifa Abdul Hakim (Pakistan); Ali Shariati (Iran); Farag Foda (Egypt); Habib Borguiba (Tunisia); Javed Ahmad Ghamidi (Pakistan).

Islamic Socialism

Islamic Socialism emerged as a branch of Islamic Modernism. Whereas Islamic Modernism had largely been sympathetic towards the idea of capitalism, a branch of it broke away after the 1917 communist revolution in Russia, to become known as Islamic Socialism.

Islamic Socialism attempted to equate Qur’anic concepts of equality and charity with modern Socialist economics. This idea when merged with active politics was aimed to trigger a cultural, intellectual and political renaissance in the Muslim world through whichever means necessary: revolution, the democratic process or through a military coup.

Islamic Socialism was also anti-clerical, socially liberal and mostly sympathetic towards communist powers, the Soviet Union and China. But it was not secular, as such. Islam was an important aspect of the idea. However, ideologues who shaped Islamic Socialism saw the ulema and clerics as agents of backwardness and exploitation. They insisted that there was no room for a theocracy in Islamic Socialism.

Islamic Socialism was a powerful populist idea in various Muslim countries from the 1930s till the early 1970s, before fading away.

Early Manifestations: The Waisi Movement (Soviet Union); Ubaidullah Sindhi (India); Ghulam Ahmad Parvez (India/Pakistan); Tan Malaka (Indonasia).

Contemporary Manifestations: Hanif Rammay (Pakistan); Pakistan People’s Party (Pakistan); Ali Shariati (Iran); Mujahideen-i-Khalq (Iran); Muammar Qaddafi (Libya); National Liberation Front (Algeria); Peoples Democratic Party (Afghanistan); Palestine Liberation Organization (Global).

Arab Socialism/Ba’ath Socialism

Arab Socialism and Ba’ath Socialism both evolved from Pan-Arabism or Arab Nationalism which began being formulated from the early 20th century as the Arab response to the rise of European colonialism. Both were also influenced by Islamic Socialism and Islamic Modernism.

In the Middle East, Islamic Socialism evolved into becoming a more nationalistic and revolutionary idea, mainly due to the creation of Israel (in 1948) and the expulsion of thousands of Palestinians from the area.

Syrian Arab nationalists, Michel Aflaq, Salah ad-Din Bitar are believed to be the originators of the Middle Eastern strain of Islamic Socialism that expressed itself as Arab Socialism and Ba’ath Socialism.

After studying the economic and political decline of the Arab peoples around the world, Aflaq and Bitar advocated the creation of a united Arab state.

For this they recast Arab nationalism by infusing into it a heavy dose of socialist economic ideas, progressive cultural and social outlook, and by reworking the idea of Islam inherent in it by evoking ‘Qur’an’s revolutionary spirit’ to counter injustice and inequality.

Aflaq and Bitar claimed that this would lead to a renaissance in the Arab world, turning it into an economic and political power.

Arab and Ba’ath Socialism appealed to the unity of all Arab nations on the basis of language/culture (Arab) and on the faith most Arabs followed (Islam).

They suggested that the Arab nations were being undermined by five forces: European colonialism (driven by capitalism); Soviet Communism; ‘decadent monarchies’ in Arab countries; Islamic conservatism; and the clergy who were keeping Arab societies in the clutches of backwardness.

Both the ideas offered a path between Western capitalism and Soviet communism by suggesting that all Arab nations come together as one state under a single ‘vanguard party’ of Arab nationalists who would impose socialist economic policies, modernize society through education, science and culture, separate religion from the state but continue being inspired by the egalitarian concepts of Islam.

In spite of being staunchly secular, Arab and Ba’ath Socialism celebrated Islam as proof of ‘Arab genius’, and a testament of Arab culture, values and thought.

Both the ideas flourished in the Middle East between the late 1940s and early 1970s, inspiring and enacting Arab Socialist regimes in Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Algeria, North Yemen, Sudan and Somalia before receding from the early 1970s onwards.

Early Manifestations: Michel Aflaq & Salah ad-Din Bitar (Syria); Gammal Abdel Nasser (Egypt).

Contemporary Manifestations: Arab Socialist Party (Egypt); Syrian Ba’ath Socialist Party (Syria); Iraq Ba’ath Socialist Party (Iraq); National Liberation Front (Algeria); National Liberation Front (Yemen); Muammar Qaddafi (Libya); Sudan Socialist Union (Sudan); Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (Somalia); PLO.

[1] Encyclopedia of Islam & Muslim World (Gale Globe, 2004)

[2] B Lewis: The Political Language of Islam (University of Chicago Press, 1988) p.117

[3] Oliver Roy: The Failure of Political Islam (Harvard University Press, 1998)

[4] Oxford English Dictionary (Oxford University Press, 2014)

[5] M Mozzafari: Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions (Routledge, 2007) p.18

[6] WE Shepard: Syed Qutb’s Doctrine of Jahiliyya, International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies (Novemeber 2003) p.521

[7] Ibid. p.545

[8] Aziz Ahmad: Islamic Modernism in India and Pakistan (Oxford University Press, 1967) p.124.

[9] A. Khalid: Jadidism in Central Asia (University of California Press, 1998) p.204