The area inhabited by the Pashtuns, Tajiks, Hazara, Uzbeks and Turkomans, called Ariana in ancient times and Khurasan in medieval times, came to be known as Afghanistan during the reign of Ahmad Shah (1747--1772).

Ahmad Shah Baba who became Afghan king at the age of 25 is the one who sacked Delhi in 1756 at the invitation of famous Muslim scholar Shah Waliullah. It is during his reign that the Afghan empire ended up stretching from eastern Iran to the Indus River and it is he who is credited as the founder of modern-day Afghanistan.

It goes to the credit of Ahmad Shah Baba that he mended the fault lines between the ever colliding Barakzais and Sadozais (the main contending Pasthun tribes) and brought others such as Farsi-speaking Tajiks, Shia Hazara, Uzbeks and Turkomans under one umbrella which culminated in the beginning of a common consciousness.

The most dominant ethnic group which has ruled this area throughout are the Pashtums - organized into numerous tribes, sub-tribes, clans and extended families. Each tribe and sub-tribe traces its ancestry back to some great forefather. Most therefore have a name that ends in “zai” which means “children of”, like the prefix “Mac” found in the names of Scottish clans till today.

Ahmad Shah belonged to the Sadozai clan which means that he and his relatives were descended from a man named Sado. Another powerful clan, descended from Barak, was called Barakzai. These two tribes further up belonged to the Abdali confederation, which means that they all descend from some much more remote ancestor named Abdal.

The Abdalis had enmity/rivalry with Ghilzais, who too lived in the area of Kandahar and around. The Ghilzais had been the most dominant Pashtuns for centuries. It is the Ghilzais, in India known as Khiljis, who were the Sultans of Delhi in the 15th century.

Ahmad Shah Abdali started his reign by awarding himself the grandiose nickname of “Durr-i-Durran” (The Pearl of Pearls). As his fame and stature grew, Abdali Pashtuns all started calling themselves Durranis, and the very word Abdali passed right out of history.

Structure of Afghan society

Ever since the death of Ahmad Shah Baba in 1772, three factors have primarily moulded the flow of events in Afghanistan:

First, the deeply rooted internal structure of Afghan society.

Second, the tragedy of history and unending play of “The Great Game” which involves superpowers tussling for strategic objectives.

Third, the urge of the Afghan people to recreate at least the semblance of the past glory and grandeur when the Afghan empire under Ahmad Shah Baba stretched from the heart of modern day Iran to the Indian Ocean and included Kashmir, being second in power only to the Ottomans in the Muslim world.

Barring the cities such as Kabul, Kandahar, Herat and Mazar-i-Sharif, thousands of villages dotted the hills and plains, each of them a more or less autonomous political and economic unit, in which power lay in the hands of khans, maliks, muftis and Qazis and not with the central government.

Afghans are fiercely independent. They have always fought back and retrieved their lands with honour and dignity.

A majority of Afghans is extremely orthodox Sunni Muslim. Such a people, who honoured primarily the dictates of religion, custom, culture, tribe, clan, village and family could not be controlled and subdued easily.

Attempts to impose centralized control have often been forcefully resisted by the Old Afghanistan - an organic network of peasants and feudal lords, tribal leaders and grassroots religious clerics, nomads and nomadic chieftains, self- governing village republics and tribal guerrilla armies. To this fell victim King Amanullah (1919- 1929) who tried to push through liberal Western reforms in Afghanistan in an irrational and unwise manner, showing no regard for the centuries’ old traditions, customs and religious feelings. The same came to be the fate of the left-wing rulers who came to power after Sardar Daud was topped on April 27, 1978.

The Game played between Russia and Great Britain

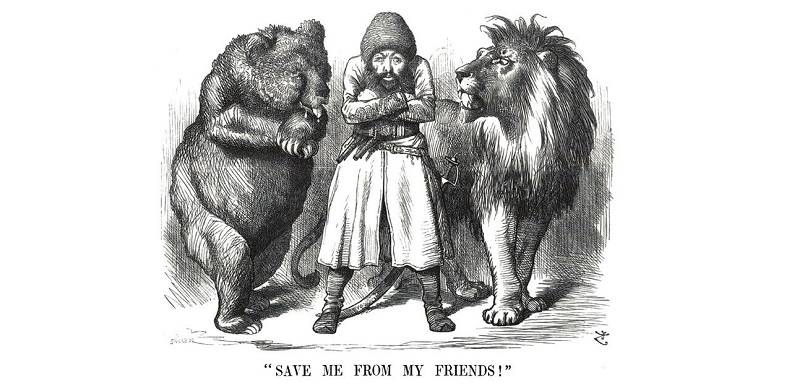

In the 19th and 20th Centuries, Great Britain was confronting the Russian Bear on a long front stretching from Central Asia to Central Europe.

In essence, the term pertains to the moves and manoeuvres made by the then two superpowers to gain strategic edge against each other on the chessboard of Asia. The third player, Afghanistan, much weaker than the other two, which was unfortunately squeezed between the two, attempted to play one power against the other, using each to keep the other out from its territory.

To comprehend as to why the two empires so recklessly played this game, one has to first have a view of what each empire then looked like.

By the close of the 19th century, the British Empire covered 23 percent of the world's land surface and ruled over a quarter of the people on Earth. The island itself had 2 percent of the world's population but 45 percent of the world's industry. It consumed five times as much energy as the United States and 155 times as much as Russia. It was rightly said that in this empire “the sun never sets”. When Queen Victoria came to the throne in 1873, Great Britain already governed Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and parts of South America and Africa. Great Britain had technological edge in almost all fields. Its navy being the biggest and the strongest with hundreds of ships and more than 200,000 sailors had virtual monopoly over all the oceanic routes of the world.

The hold of the British Empire over the Indian Subcontinent, however, appeared to be threatened as the small Muscovite Principality(1283 -1547) centered around Moscow had now become the Russian Empire stretching from the Black Sea to the Pacific Ocean, which for some time also had colonies in Americas (1732 -1868). This new force took over Persian-ruled territories of Armenia and Azerbaijan in 1828, and the Chinese territory of Manchuria in 1860. From 1865 to 1876, Russian troops took the cities of Tashkent, Bukhara, Samarkand and the Khanate of Kokand, besides bringing the Khan of Khiva under its protection. Its power now extended to the very banks of the Amu River. Only Afghanistan stood between them and the British in India. It was a bad place for a little country like Afghanistan to be situated.

Russia 's occupation of Merv in 1884- with Russia’s frontier now less than 200 miles from Herat, commencement of construction on the Trans-Caspian Railway and its extension to Samarkand and Tashkent added fuel to the fire. As Lord Curzon put it in 1901. ''We wanted buffer states between ourselves and Russia, one by one, each of these had been crushed out of existence”.

Though Russia is the world's largest country, covering more than 6.6 million square miles and stretching halfway around the world, it is devoid of year round access to warm waters. Its openings through Bosporus, St. Petersburg and the Arctic Ocean are risky, besides the last two being clogged for about 9 months in a year. Russia, thus, was desperate to have permanent access to warm waters of the Arabian Sea but in between stood Afghanistan and the mighty British Empire.

From the British point of view, there was real concern about Russia's intentions and capabilities and about the threat that its expansion posed to the defences of India. At one point the British Prime Minister Disraeli advised the Queen to be ready to authorise the troops to clear Central Asia of the Muscovites and drive them into the Caspian. It was also feared that Russia's rise and the development of new land based trade routes would disrupt lucrative British trade with China where more than 80 percent of all revenue collected was paid by Britain and the British Companies whose ships also carried more than four- fifth of China's total trade.

Great Britain attacked Afghanistan twice to bring it under its complete thumb in 1839 and 1878 but could not succeed, so much so that in 1841, out of 16,500 retreating personnel, only one Dr Brydon could make it to Jalalabad from Kabul.

Over a period of time, both Russia and Great Britain settled on making Afghanistan a buffer state between the two in true sense. Afghan King Abdul Rehman, called the Iron Amir, proved to be more pragmatic and wiser and it is he who sat down with the foreign minister of the Raj, Mortimer Durand in 1893, and finalised the contours of the boundary between Afghanistan and British India, known as the Durand Line. This very policy of neutrality was carried forward by Nadir Shah and his family who used it to squeeze resources out of both sides (first from Russia and Great Britain and then from the Soviet Union and the USA). It is during their rule that Soviet Union built the two-mile long Salang Tunnel at 11,100 feet, besides laying down a vast network of roads, bridges, reservoirs etc. while US started work on the prestigious Helmand Valley Project and many others in different fields.

At this point of time, Afghanistan was opening up and moving forward when suddenly Sardar Daud was deposed and after a few years Soviet Union physically intervened. These developments intensified the ferocious contest between the two world powers. The rest is history - well known to everyone. Since then, Afghanistan is burning and Pakistan got sucked into this quagmire because of unavoidable regional imperatives.

Before I end it, one pertinent question: is the Great Game in this region now over?

To my mind, it is not. In and around the region encompassing Central Asia, Afghanistan and Pakistan, a far bigger New Game is in the offing.

How and why and with which players?

The Emerging New Great Game

The content of this Great Game will be vividly clear if we look at what lies below the landmass from Black Sea to Central Asia.

The combined proved crude reserves under the Caspian Sea alone are nearly twice those of the entire United States. The border areas of Russia and Kazakhstan contain an estimated 42 trillion cubic feet of natural gas as well as liquefied gas and crude oil. The potential of Kurdistan is evident from the fact that per day yield of its one well, Taq Taq, has now risen to 250,000 which in 2007 was merely 2,000. The Donbas Basin that straddles Ukraine's eastern frontier with Russia has extractable reserves of coal deposits of around 10 billion tons. This area also has reserves of 1.4 billion barrels of oil, 2.4 billion cubic feet of natural gas and considerable estimated volumes of natural gas liquids.

Turkmenistan has more than 700 trillion cubic feet of natural gas below its ground, the fourth largest supplies in the world. The goldmines of Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan that form part of the Tian Shan belt are second only to those of South Africa for the size of its deposits. Kazakhstan is rich in rare earth deposits such as beryllium and dysprosium that are vital for the manufacture of mobile phones, laptops and rechargeable batteries. Kazakhstan also has deposits of uranium and plutonium that are essential for nuclear energy and nuclear warheads.

Even the earth of this huge landmass is rich and valuable. Once, it was the horses of Central Asia (sold more than 100,000 in a year) that were a prized commodity in India and China. Today large parts of the grazing land of the steppes have been transformed to become astonishingly productive grain fields of Southern Russia and Ukraine (the wheat belt which Hitler tried to snatch from Soviet Union and where his forces bogged down and ultimately lost the Great War).

Interesting to note that one NGO has found that close to a billion dollars' worth of soil of this belt is dug up as such and sold annually in Ukraine alone.

When we add the dynamics of Gawadar and Chahbahar ports to this, and the bitter rivalries between USA and India on the one side and China and Russia on the other, and the overarching reach of One Belt, One Road/CPEC in the regional chessboard of dominance, we can rest assured that much more is in the offing in future in this part of the Eurasian tableland.

The author is a former Member of the Federal Board of Revenue, Pakistan with interest in writing on unknown facets of history. Email: maslamshad11@gmail.com

Ahmad Shah Baba who became Afghan king at the age of 25 is the one who sacked Delhi in 1756 at the invitation of famous Muslim scholar Shah Waliullah. It is during his reign that the Afghan empire ended up stretching from eastern Iran to the Indus River and it is he who is credited as the founder of modern-day Afghanistan.

It goes to the credit of Ahmad Shah Baba that he mended the fault lines between the ever colliding Barakzais and Sadozais (the main contending Pasthun tribes) and brought others such as Farsi-speaking Tajiks, Shia Hazara, Uzbeks and Turkomans under one umbrella which culminated in the beginning of a common consciousness.

The most dominant ethnic group which has ruled this area throughout are the Pashtums - organized into numerous tribes, sub-tribes, clans and extended families. Each tribe and sub-tribe traces its ancestry back to some great forefather. Most therefore have a name that ends in “zai” which means “children of”, like the prefix “Mac” found in the names of Scottish clans till today.

Ahmad Shah belonged to the Sadozai clan which means that he and his relatives were descended from a man named Sado. Another powerful clan, descended from Barak, was called Barakzai. These two tribes further up belonged to the Abdali confederation, which means that they all descend from some much more remote ancestor named Abdal.

The Abdalis had enmity/rivalry with Ghilzais, who too lived in the area of Kandahar and around. The Ghilzais had been the most dominant Pashtuns for centuries. It is the Ghilzais, in India known as Khiljis, who were the Sultans of Delhi in the 15th century.

Ahmad Shah Abdali started his reign by awarding himself the grandiose nickname of “Durr-i-Durran” (The Pearl of Pearls). As his fame and stature grew, Abdali Pashtuns all started calling themselves Durranis, and the very word Abdali passed right out of history.

Structure of Afghan society

Ever since the death of Ahmad Shah Baba in 1772, three factors have primarily moulded the flow of events in Afghanistan:

First, the deeply rooted internal structure of Afghan society.

Second, the tragedy of history and unending play of “The Great Game” which involves superpowers tussling for strategic objectives.

Third, the urge of the Afghan people to recreate at least the semblance of the past glory and grandeur when the Afghan empire under Ahmad Shah Baba stretched from the heart of modern day Iran to the Indian Ocean and included Kashmir, being second in power only to the Ottomans in the Muslim world.

Barring the cities such as Kabul, Kandahar, Herat and Mazar-i-Sharif, thousands of villages dotted the hills and plains, each of them a more or less autonomous political and economic unit, in which power lay in the hands of khans, maliks, muftis and Qazis and not with the central government.

Afghans are fiercely independent. They have always fought back and retrieved their lands with honour and dignity.

A majority of Afghans is extremely orthodox Sunni Muslim. Such a people, who honoured primarily the dictates of religion, custom, culture, tribe, clan, village and family could not be controlled and subdued easily.

Attempts to impose centralized control have often been forcefully resisted by the Old Afghanistan - an organic network of peasants and feudal lords, tribal leaders and grassroots religious clerics, nomads and nomadic chieftains, self- governing village republics and tribal guerrilla armies. To this fell victim King Amanullah (1919- 1929) who tried to push through liberal Western reforms in Afghanistan in an irrational and unwise manner, showing no regard for the centuries’ old traditions, customs and religious feelings. The same came to be the fate of the left-wing rulers who came to power after Sardar Daud was topped on April 27, 1978.

The Game played between Russia and Great Britain

In the 19th and 20th Centuries, Great Britain was confronting the Russian Bear on a long front stretching from Central Asia to Central Europe.

In essence, the term pertains to the moves and manoeuvres made by the then two superpowers to gain strategic edge against each other on the chessboard of Asia. The third player, Afghanistan, much weaker than the other two, which was unfortunately squeezed between the two, attempted to play one power against the other, using each to keep the other out from its territory.

To comprehend as to why the two empires so recklessly played this game, one has to first have a view of what each empire then looked like.

By the close of the 19th century, the British Empire covered 23 percent of the world's land surface and ruled over a quarter of the people on Earth. The island itself had 2 percent of the world's population but 45 percent of the world's industry. It consumed five times as much energy as the United States and 155 times as much as Russia. It was rightly said that in this empire “the sun never sets”. When Queen Victoria came to the throne in 1873, Great Britain already governed Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and parts of South America and Africa. Great Britain had technological edge in almost all fields. Its navy being the biggest and the strongest with hundreds of ships and more than 200,000 sailors had virtual monopoly over all the oceanic routes of the world.

The hold of the British Empire over the Indian Subcontinent, however, appeared to be threatened as the small Muscovite Principality(1283 -1547) centered around Moscow had now become the Russian Empire stretching from the Black Sea to the Pacific Ocean, which for some time also had colonies in Americas (1732 -1868). This new force took over Persian-ruled territories of Armenia and Azerbaijan in 1828, and the Chinese territory of Manchuria in 1860. From 1865 to 1876, Russian troops took the cities of Tashkent, Bukhara, Samarkand and the Khanate of Kokand, besides bringing the Khan of Khiva under its protection. Its power now extended to the very banks of the Amu River. Only Afghanistan stood between them and the British in India. It was a bad place for a little country like Afghanistan to be situated.

Russia 's occupation of Merv in 1884- with Russia’s frontier now less than 200 miles from Herat, commencement of construction on the Trans-Caspian Railway and its extension to Samarkand and Tashkent added fuel to the fire. As Lord Curzon put it in 1901. ''We wanted buffer states between ourselves and Russia, one by one, each of these had been crushed out of existence”.

Though Russia is the world's largest country, covering more than 6.6 million square miles and stretching halfway around the world, it is devoid of year round access to warm waters. Its openings through Bosporus, St. Petersburg and the Arctic Ocean are risky, besides the last two being clogged for about 9 months in a year. Russia, thus, was desperate to have permanent access to warm waters of the Arabian Sea but in between stood Afghanistan and the mighty British Empire.

From the British point of view, there was real concern about Russia's intentions and capabilities and about the threat that its expansion posed to the defences of India. At one point the British Prime Minister Disraeli advised the Queen to be ready to authorise the troops to clear Central Asia of the Muscovites and drive them into the Caspian. It was also feared that Russia's rise and the development of new land based trade routes would disrupt lucrative British trade with China where more than 80 percent of all revenue collected was paid by Britain and the British Companies whose ships also carried more than four- fifth of China's total trade.

Great Britain attacked Afghanistan twice to bring it under its complete thumb in 1839 and 1878 but could not succeed, so much so that in 1841, out of 16,500 retreating personnel, only one Dr Brydon could make it to Jalalabad from Kabul.

Over a period of time, both Russia and Great Britain settled on making Afghanistan a buffer state between the two in true sense. Afghan King Abdul Rehman, called the Iron Amir, proved to be more pragmatic and wiser and it is he who sat down with the foreign minister of the Raj, Mortimer Durand in 1893, and finalised the contours of the boundary between Afghanistan and British India, known as the Durand Line. This very policy of neutrality was carried forward by Nadir Shah and his family who used it to squeeze resources out of both sides (first from Russia and Great Britain and then from the Soviet Union and the USA). It is during their rule that Soviet Union built the two-mile long Salang Tunnel at 11,100 feet, besides laying down a vast network of roads, bridges, reservoirs etc. while US started work on the prestigious Helmand Valley Project and many others in different fields.

At this point of time, Afghanistan was opening up and moving forward when suddenly Sardar Daud was deposed and after a few years Soviet Union physically intervened. These developments intensified the ferocious contest between the two world powers. The rest is history - well known to everyone. Since then, Afghanistan is burning and Pakistan got sucked into this quagmire because of unavoidable regional imperatives.

Before I end it, one pertinent question: is the Great Game in this region now over?

To my mind, it is not. In and around the region encompassing Central Asia, Afghanistan and Pakistan, a far bigger New Game is in the offing.

How and why and with which players?

The Emerging New Great Game

The content of this Great Game will be vividly clear if we look at what lies below the landmass from Black Sea to Central Asia.

The combined proved crude reserves under the Caspian Sea alone are nearly twice those of the entire United States. The border areas of Russia and Kazakhstan contain an estimated 42 trillion cubic feet of natural gas as well as liquefied gas and crude oil. The potential of Kurdistan is evident from the fact that per day yield of its one well, Taq Taq, has now risen to 250,000 which in 2007 was merely 2,000. The Donbas Basin that straddles Ukraine's eastern frontier with Russia has extractable reserves of coal deposits of around 10 billion tons. This area also has reserves of 1.4 billion barrels of oil, 2.4 billion cubic feet of natural gas and considerable estimated volumes of natural gas liquids.

Turkmenistan has more than 700 trillion cubic feet of natural gas below its ground, the fourth largest supplies in the world. The goldmines of Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan that form part of the Tian Shan belt are second only to those of South Africa for the size of its deposits. Kazakhstan is rich in rare earth deposits such as beryllium and dysprosium that are vital for the manufacture of mobile phones, laptops and rechargeable batteries. Kazakhstan also has deposits of uranium and plutonium that are essential for nuclear energy and nuclear warheads.

Even the earth of this huge landmass is rich and valuable. Once, it was the horses of Central Asia (sold more than 100,000 in a year) that were a prized commodity in India and China. Today large parts of the grazing land of the steppes have been transformed to become astonishingly productive grain fields of Southern Russia and Ukraine (the wheat belt which Hitler tried to snatch from Soviet Union and where his forces bogged down and ultimately lost the Great War).

Interesting to note that one NGO has found that close to a billion dollars' worth of soil of this belt is dug up as such and sold annually in Ukraine alone.

When we add the dynamics of Gawadar and Chahbahar ports to this, and the bitter rivalries between USA and India on the one side and China and Russia on the other, and the overarching reach of One Belt, One Road/CPEC in the regional chessboard of dominance, we can rest assured that much more is in the offing in future in this part of the Eurasian tableland.

The author is a former Member of the Federal Board of Revenue, Pakistan with interest in writing on unknown facets of history. Email: maslamshad11@gmail.com