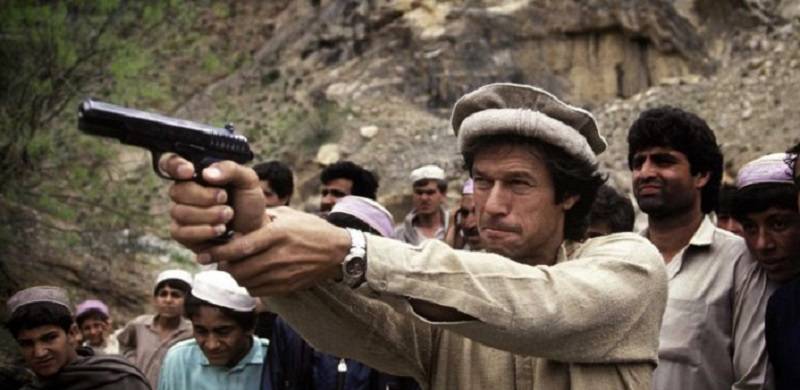

In his passionate speech to the parliament, Prime Minister Imran Khan stuck to his narrative that it was ‘their’ war in which we sacrificed 70,000 people and that we were ‘not recognised.’ He argued that Al-Qaeda and the Taliban never intended to cause any harm to Pakistan and that becoming part of the U.S.-led War on Terror was a mistake. Such narratives may have helped to get him into office, so sticking to them is perhaps the right thing to do politically – but the facts might be an entirely different story.

The narrative championed by Imran Khan is popular amongst many people of our country, whose religiosity itself suffers a crisis whenever they imagine that another person of their religion is responsible for the killing of their brethren. It is difficult for people of such a mindset to fathom that the children in the Army Public School tragedy were massacred not by the Americans, but by people who – if nothing else – believed in the same God as us!

Hindsight is also at times a blessing – and it certainly is so for our current Prime Minister when he criticizes the choices made around 2001. Pakistan didn’t have many options at the time when the U.S. decided to attack Afghanistan – and while the exact arrangements could have been managed better, there was not much room to manoeuvre. The country was under extreme sanctions and wanted legitimacy for its nuclear weapon which was already being dubbed as the 'Islamic Bomb.'

The PM also fails to appreciate that when in government, or even as a rebel fighting force, the Taliban in Afghanistan are not merely proxies that are in complete control of the state of Pakistan. They have shown on many occasions that they can act on their own. They are ideologically motivated fighters whose goal was not only to consolidate their Emirate, but also expand it to the neighbouring Pashtun belt in Pakistan. In fact, they had never accepted the Durand Line for the same reason.

Meanwhile, Al-Qaeda had been openly hostile to Pakistan and wanted there to be a conflict in the South Asian Subcontinent, which it could later use for its own gains. The idea was always to bring the world's superpowers to the region, as they couldn’t be attacked from here. When Pakistan's state made its decision to fight them – to whatever extent it chose to do so – the question was of how to take on these groups. Not taking them on at all, as PM Khan suggests, would not have appeared as a valid policy option in that moment.

Let us consider the part where the PM is actually correct. Pakistan faces immense challenges after the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and in all likelihood would be scapegoated for the failures of the international (ISAF) forces to turn the tide. The revival of a civil war around Kabul is bound to happen and it would have direct consequences on Pakistan.

In such a scenario, the right thing to do for the PM would be to get all the political actors on the same page and create consensus around a foreign policy that can withstand international pressure and not repeat the mistakes of the past.

The author is a lecturer at University of London Affiliate Centres based in Islamabad.

The narrative championed by Imran Khan is popular amongst many people of our country, whose religiosity itself suffers a crisis whenever they imagine that another person of their religion is responsible for the killing of their brethren. It is difficult for people of such a mindset to fathom that the children in the Army Public School tragedy were massacred not by the Americans, but by people who – if nothing else – believed in the same God as us!

Hindsight is also at times a blessing – and it certainly is so for our current Prime Minister when he criticizes the choices made around 2001. Pakistan didn’t have many options at the time when the U.S. decided to attack Afghanistan – and while the exact arrangements could have been managed better, there was not much room to manoeuvre. The country was under extreme sanctions and wanted legitimacy for its nuclear weapon which was already being dubbed as the 'Islamic Bomb.'

The PM also fails to appreciate that when in government, or even as a rebel fighting force, the Taliban in Afghanistan are not merely proxies that are in complete control of the state of Pakistan. They have shown on many occasions that they can act on their own. They are ideologically motivated fighters whose goal was not only to consolidate their Emirate, but also expand it to the neighbouring Pashtun belt in Pakistan. In fact, they had never accepted the Durand Line for the same reason.

Meanwhile, Al-Qaeda had been openly hostile to Pakistan and wanted there to be a conflict in the South Asian Subcontinent, which it could later use for its own gains. The idea was always to bring the world's superpowers to the region, as they couldn’t be attacked from here. When Pakistan's state made its decision to fight them – to whatever extent it chose to do so – the question was of how to take on these groups. Not taking them on at all, as PM Khan suggests, would not have appeared as a valid policy option in that moment.

Let us consider the part where the PM is actually correct. Pakistan faces immense challenges after the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and in all likelihood would be scapegoated for the failures of the international (ISAF) forces to turn the tide. The revival of a civil war around Kabul is bound to happen and it would have direct consequences on Pakistan.

In such a scenario, the right thing to do for the PM would be to get all the political actors on the same page and create consensus around a foreign policy that can withstand international pressure and not repeat the mistakes of the past.

The author is a lecturer at University of London Affiliate Centres based in Islamabad.