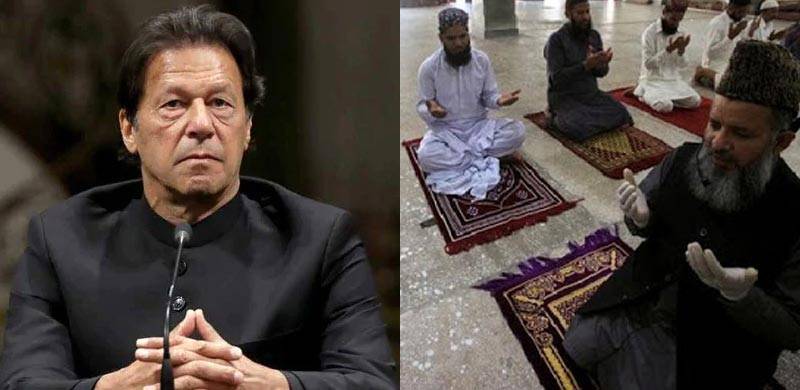

Imran Khan is being criticised for allowing congregational Tarawih prayers during Ramzan but Sibtain Naqvi believes that given Pakistan's circumstances and history, the prime minister didn't have much of a choice.

In a few days, Ramzan will start and there are concerns that the social distancing recommended for battling the Coronavirus will not be followed. On April 18, President Arif Alvi announced that mosques would be allowed to hold evening tarawih prayers during the month. Earlier, the government had also allowed congregational prayers in mosques, albeit with the recommendation that it be limited and with precautions.

Given the serious nature of the disease spreading, the potential for deaths and knowing that Pakistan’s fragile public health system is already overburdened, the decision to allow daily gatherings in mosques could prove to be disastrous. While the government has laid out precautionary conditions focused on hygiene and social distancing, implementation and monitoring of these conditions across thousands of mosques will be a major challenge. If Easter celebrations could be held from homes, why not tarawih prayers? This reeks of discrimination.

The fact that the federal government has eventually capitulated to the ulema’s demands may be disappointing but not unexpected. Many are pointing out that Pakistan is the only Muslim-majority country in the world that has allowed public religious gatherings. Even Saudi Arabia, the lodestone of Muslims and whose religious authority is recognized by many, has not allowed them in an effort to limit social contact. Iran, officially a theocracy, has also shut down the religious sites for the same reason. Pakistan does seem to be the only major Muslim-majority country allowing public congregations on the basis of Islam. Out of the 50 or so Muslim-majority countries what makes Pakistan so unique?

The simplest answer is that none of those countries were founded on the basis of Islam. To use more prominent examples, in the case of Saudi Arabia, its official name is the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia - or the Kingdom of Saud. Iran predates its Islamic revolution. Generally speaking, countries are based on linguistics, geography, colonial-era boundaries, etc.

In Pakistan’s case, Islam is at the very heart of its ideology and has been since 1937. The Muslim League, after performing poorly in the elections, embraced its role as the party that would create a homeland for the Muslims of India. Islam was used as a case for a separate nation and by the time Pakistan came into being, Jinnah had given plenty of statements that made Islam a foundation of Pakistan’s ideology. Although he made it clear he did not want a theocracy, there were speeches in which he referred to “Muslim ideology” that would be shared with others in the future state of Pakistan.

A secular man, his vision of a country which would have a separation between state and religion and yet embody Islamic principles, proved to be too sophisticated for his Muslim constituents to understand. Shortly after he died, his Oxford-educated lieutenant introduced the Objectives Resolution and set the path for the country becoming if not a theocracy, then one in which religion and politics would be intertwined. The 1956 constitution included the Objectives Resolution as a preamble and Pakistan’s constitutionalist politicians, many of whom were well-educated, upper-class types, and liberals in their personal lives, named the country Islamic Republic of Pakistan. General Zia-ul-Haq has been rightly labeled a zealot, but every government, civilian or military, has kowtowed to the clergy.

The case of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto is particularly illuminating. At a public rally in Lahore in 1972, he openly taunted his Islamist opponents by sipping from a flask. When heckled for it, Bhutto said he only drank alcohol, not the blood of the people like the Mullahs did. Back then, confident of his power, he was confrontational. But by 1977 he was appeasing Islamists in a way that would have made Chamberlain proud, introducing prohibition, declaring Friday a holiday, and so on.

After Zia’s Islamization process began, the space for secularists shrank further and the Oxford-educated Benazir Bhutto thought it wise to brand herself as “Daughter of the East” and try to work along with the clergy who pilloried her at every opportunity. Her opponent Nawaz Sharif went a step further, styling himself as the “Ameer-ul-Momineen” and in 1998 trying to introduce the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan which would have made Sharia Law the supreme law in Pakistan. General Musharraf took on the rightist militants at Lal Masjid, spoke about “Enlightened Moderation” and supported the war on terror but faced with the clergy’s opposition on his attempt to remove the religion section in the Pakistani passport, he backed down and also failed to get the bill to protect women from assault passed from the assembly.

Considering the long confluence of Islam and politics in this country, it is hardly surprising that the PTI government has thrown in the towel when it came to Islamic religious gatherings. Can the army be used for enforcing the policy or countering the clergy’s power with its own? Well, the case is complex. While the army can put away disruptive elements such as Khadim Hussain Rizvi with ease, taking on the clergy on a matter of faith would prove to be a bigger challenge. In a country where faith is a life-and-death issue and overt religiosity is a way of life, a show of arms might lead to street agitation beyond control. The only solution would have been a joint statement from the clergy themselves that would guide their flock of believers, but that did not come. Perhaps the senior clergy, even those who are relatively moderate, felt that this statement might alienate their followers who would then start supporting the more extreme members of their fraternity.

Whatever the case might be, the PTI government is allowing the mosques to host tarawih, when the rest of the Muslim world is not. By doing so, it is endangering the lives of the people, taking the risk of COVID-19 spreading further and courting absolute disaster. Not only this, President Arif Alvi feels the 20 tactics outlined for safe tarawih prayers can be followed by other countries such as Saudi Arabia.

Whether it is Jinnah’s state for Muslims run on the basis of Islamic values, Liaqat Ali Khan’s Islamic republic, Bhutto’s “Islamic Socialism”, Nawaz Sharif’s attempted Shariah state or Imran Khan’s “Riyasat-e-Madina”, Islam has always had a place in Pakistani politics. Pakistan’s political fields have been irrigated by Islam since 1937 and given the fertile soil, we are continuously reaping the crop.

In a few days, Ramzan will start and there are concerns that the social distancing recommended for battling the Coronavirus will not be followed. On April 18, President Arif Alvi announced that mosques would be allowed to hold evening tarawih prayers during the month. Earlier, the government had also allowed congregational prayers in mosques, albeit with the recommendation that it be limited and with precautions.

Given the serious nature of the disease spreading, the potential for deaths and knowing that Pakistan’s fragile public health system is already overburdened, the decision to allow daily gatherings in mosques could prove to be disastrous. While the government has laid out precautionary conditions focused on hygiene and social distancing, implementation and monitoring of these conditions across thousands of mosques will be a major challenge. If Easter celebrations could be held from homes, why not tarawih prayers? This reeks of discrimination.

The fact that the federal government has eventually capitulated to the ulema’s demands may be disappointing but not unexpected. Many are pointing out that Pakistan is the only Muslim-majority country in the world that has allowed public religious gatherings. Even Saudi Arabia, the lodestone of Muslims and whose religious authority is recognized by many, has not allowed them in an effort to limit social contact. Iran, officially a theocracy, has also shut down the religious sites for the same reason. Pakistan does seem to be the only major Muslim-majority country allowing public congregations on the basis of Islam. Out of the 50 or so Muslim-majority countries what makes Pakistan so unique?

The simplest answer is that none of those countries were founded on the basis of Islam. To use more prominent examples, in the case of Saudi Arabia, its official name is the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia - or the Kingdom of Saud. Iran predates its Islamic revolution. Generally speaking, countries are based on linguistics, geography, colonial-era boundaries, etc.

In Pakistan’s case, Islam is at the very heart of its ideology and has been since 1937. The Muslim League, after performing poorly in the elections, embraced its role as the party that would create a homeland for the Muslims of India. Islam was used as a case for a separate nation and by the time Pakistan came into being, Jinnah had given plenty of statements that made Islam a foundation of Pakistan’s ideology. Although he made it clear he did not want a theocracy, there were speeches in which he referred to “Muslim ideology” that would be shared with others in the future state of Pakistan.

A secular man, his vision of a country which would have a separation between state and religion and yet embody Islamic principles, proved to be too sophisticated for his Muslim constituents to understand. Shortly after he died, his Oxford-educated lieutenant introduced the Objectives Resolution and set the path for the country becoming if not a theocracy, then one in which religion and politics would be intertwined. The 1956 constitution included the Objectives Resolution as a preamble and Pakistan’s constitutionalist politicians, many of whom were well-educated, upper-class types, and liberals in their personal lives, named the country Islamic Republic of Pakistan. General Zia-ul-Haq has been rightly labeled a zealot, but every government, civilian or military, has kowtowed to the clergy.

The case of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto is particularly illuminating. At a public rally in Lahore in 1972, he openly taunted his Islamist opponents by sipping from a flask. When heckled for it, Bhutto said he only drank alcohol, not the blood of the people like the Mullahs did. Back then, confident of his power, he was confrontational. But by 1977 he was appeasing Islamists in a way that would have made Chamberlain proud, introducing prohibition, declaring Friday a holiday, and so on.

After Zia’s Islamization process began, the space for secularists shrank further and the Oxford-educated Benazir Bhutto thought it wise to brand herself as “Daughter of the East” and try to work along with the clergy who pilloried her at every opportunity. Her opponent Nawaz Sharif went a step further, styling himself as the “Ameer-ul-Momineen” and in 1998 trying to introduce the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan which would have made Sharia Law the supreme law in Pakistan. General Musharraf took on the rightist militants at Lal Masjid, spoke about “Enlightened Moderation” and supported the war on terror but faced with the clergy’s opposition on his attempt to remove the religion section in the Pakistani passport, he backed down and also failed to get the bill to protect women from assault passed from the assembly.

Considering the long confluence of Islam and politics in this country, it is hardly surprising that the PTI government has thrown in the towel when it came to Islamic religious gatherings. Can the army be used for enforcing the policy or countering the clergy’s power with its own? Well, the case is complex. While the army can put away disruptive elements such as Khadim Hussain Rizvi with ease, taking on the clergy on a matter of faith would prove to be a bigger challenge. In a country where faith is a life-and-death issue and overt religiosity is a way of life, a show of arms might lead to street agitation beyond control. The only solution would have been a joint statement from the clergy themselves that would guide their flock of believers, but that did not come. Perhaps the senior clergy, even those who are relatively moderate, felt that this statement might alienate their followers who would then start supporting the more extreme members of their fraternity.

Whatever the case might be, the PTI government is allowing the mosques to host tarawih, when the rest of the Muslim world is not. By doing so, it is endangering the lives of the people, taking the risk of COVID-19 spreading further and courting absolute disaster. Not only this, President Arif Alvi feels the 20 tactics outlined for safe tarawih prayers can be followed by other countries such as Saudi Arabia.

Whether it is Jinnah’s state for Muslims run on the basis of Islamic values, Liaqat Ali Khan’s Islamic republic, Bhutto’s “Islamic Socialism”, Nawaz Sharif’s attempted Shariah state or Imran Khan’s “Riyasat-e-Madina”, Islam has always had a place in Pakistani politics. Pakistan’s political fields have been irrigated by Islam since 1937 and given the fertile soil, we are continuously reaping the crop.