The woman had almost lost her breathing. Her life at risk, crying for immediate help, she lay in a balcony on a dusty floor in front of the labour room of the Teaching Hospital of district Loralai, Balochistan.

With no bed, breathing intensely, she screamed at her sibling Juma Gull to get her a female gynecologist to deal with her delivery. Yet, with no emergency functionality available for her at the hospital, her body numb, she lay on dirt for two hours as she gave birth to a baby by herself.“We reached the hospital at 4 am in the morning. Our home is 10 km from the hospital. My sister aged 33 was not allowed to enter the labor room, because, there was no emergency service at that time. Even as the patient was suffering in a serious condition, a female staff member, not a gynecologist or nurse, sitting in the labour room, told us to stay out. She was saying that, ‘it is an hour too early to deal with the patient’. We were told to stay out ,unless she herself called us. She was not medically engaged with some other patient,” recalls Juma Gull.

The delivery was made after two-hours with no clinical support. Two other women of Gull’s family helped her in making a childbirth possible. “I felt as we were not considered citizens of a society, but rather left alone to deal with our health emergency by ourselves,” says Gull.

A staff worker of the hospital, on condition of anonymity, tells us what actually happened at 4 am in the morning, when he himself witnessed Juma Gull entering the hospital in a car with three women, rushing towards the labour room. “I saw them asking for help. I saw the female lying on the floor and the two others sitting beside her, looking after her. The helpless mother suffered for two hours and gave birth to a baby at 6 am. When I returned from my morning prayer, I saw she was still there on the floor.”

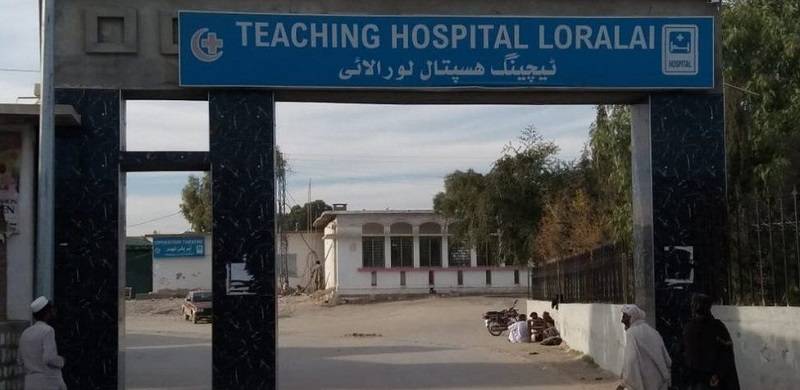

The 2017 census counts 400,000 people in the district. For their health needs, they are entirely dependent on the health services provided by the Teaching Hospital Loralai.

“We staged a sit-in protest in front of the district administration office to raise our voices for justice to be served. These cases have become a routine, and they point to inhumane attitudes and inadequacy on the part of the authorities. Thi is a massive failure of the health department.” explains Asfandyar Kakar, a human rights activist in Loralai. “Instead, the hospital administration appeared obsessed with hiding the facts. They were unwilling to reveal a true picture of their administrative practices.”

“Dealing with the childbirth process has to be done professionally. A seemingly small clinical inappropriateness may lead to a hemorrhage or critical complications such as sepsis, psychological stress, drastic drop in blood pressure and physical discomfort” says Dr. Aysha Saddiqa, head of the gynecology department at the Children's Hospital Quetta (CHQ).

The World Health Organization (WHO) alongside the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) in 2017 issued a guide for midwives and doctors, titled “Managing Complications in Pregnancy and Childbirth.”

It includes:

“Section 1: Clinical Principles: emotional and psychological support, emergencies, general care principles, antibiotic therapy, operative care principles, normal labor and childbirth, and newborn care principles.

Section 2: Symptoms: Vaginal bleeding in early pregnancy; vaginal bleeding after childbirth; Elevated blood pressure, headache, blurred vision, convulsions or loss of consciousness; Fever during pregnancy and labor; Fever after childbirth; Difficulty in breathing; Prelabor rupture of membranes; and Immediate newborn conditions or problems.

Section 3: Procedures: Induction and augmentation of labor, manual removal of placenta, and repair of vaginal and perineal tears.”

Notwithstanding all these precautionary measures for childbirth as recommended by WHO, Gull’s sister was given no such clinical care.

Mr. Raheem, President of the Paramedic Association of Loralai, recalls “Back in winter 2020, I remember that it was snowing and a similar emergency case arrived at the hospital. In absence of operating staff, they were told to rush to capital city Quetta. Think about it! What would have been that patient’s condition? She could have lost her life.”

Dostain Jamaldini, Secretary Health for Balochistan, describes how the system currently works:

“The ministry for health has facilitated Basic Health Units and Rural Health Units (BHUs/RHUs), as well as district headquarter hospitals. Primary clinical support is given initially at the basic level at BHUs and secondary services such as surgery, transplants and other major operations at central hospitals in district capitals.”

He continues:

“Talking of the case that was reported on July 10, of Teaching Hospital Loralai: indeed such occurrences take place, but they are few in number. The health department keeps trying to ensure better healthcare for the people of Balochistan. But it also tries to address the inner mismanagement, dysfunctionality and departmental errors, because this is a matter of human survival. We cannot take risks by providing no initial clinical support.”

Yet, in Pakistan, the absence of clinical support results in misery in far too many cases. Experts say that only increased fiscal outlays can help provide the healthcare facilities needed by Pakistan's citizens.

With no bed, breathing intensely, she screamed at her sibling Juma Gull to get her a female gynecologist to deal with her delivery. Yet, with no emergency functionality available for her at the hospital, her body numb, she lay on dirt for two hours as she gave birth to a baby by herself.“We reached the hospital at 4 am in the morning. Our home is 10 km from the hospital. My sister aged 33 was not allowed to enter the labor room, because, there was no emergency service at that time. Even as the patient was suffering in a serious condition, a female staff member, not a gynecologist or nurse, sitting in the labour room, told us to stay out. She was saying that, ‘it is an hour too early to deal with the patient’. We were told to stay out ,unless she herself called us. She was not medically engaged with some other patient,” recalls Juma Gull.

The delivery was made after two-hours with no clinical support. Two other women of Gull’s family helped her in making a childbirth possible. “I felt as we were not considered citizens of a society, but rather left alone to deal with our health emergency by ourselves,” says Gull.

A staff worker of the hospital, on condition of anonymity, tells us what actually happened at 4 am in the morning, when he himself witnessed Juma Gull entering the hospital in a car with three women, rushing towards the labour room. “I saw them asking for help. I saw the female lying on the floor and the two others sitting beside her, looking after her. The helpless mother suffered for two hours and gave birth to a baby at 6 am. When I returned from my morning prayer, I saw she was still there on the floor.”

The 2017 census counts 400,000 people in the district. For their health needs, they are entirely dependent on the health services provided by the Teaching Hospital Loralai.

“We staged a sit-in protest in front of the district administration office to raise our voices for justice to be served. These cases have become a routine, and they point to inhumane attitudes and inadequacy on the part of the authorities. Thi is a massive failure of the health department.” explains Asfandyar Kakar, a human rights activist in Loralai. “Instead, the hospital administration appeared obsessed with hiding the facts. They were unwilling to reveal a true picture of their administrative practices.”

“Dealing with the childbirth process has to be done professionally. A seemingly small clinical inappropriateness may lead to a hemorrhage or critical complications such as sepsis, psychological stress, drastic drop in blood pressure and physical discomfort” says Dr. Aysha Saddiqa, head of the gynecology department at the Children's Hospital Quetta (CHQ).

The World Health Organization (WHO) alongside the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) in 2017 issued a guide for midwives and doctors, titled “Managing Complications in Pregnancy and Childbirth.”

It includes:

“Section 1: Clinical Principles: emotional and psychological support, emergencies, general care principles, antibiotic therapy, operative care principles, normal labor and childbirth, and newborn care principles.

Section 2: Symptoms: Vaginal bleeding in early pregnancy; vaginal bleeding after childbirth; Elevated blood pressure, headache, blurred vision, convulsions or loss of consciousness; Fever during pregnancy and labor; Fever after childbirth; Difficulty in breathing; Prelabor rupture of membranes; and Immediate newborn conditions or problems.

Section 3: Procedures: Induction and augmentation of labor, manual removal of placenta, and repair of vaginal and perineal tears.”

Notwithstanding all these precautionary measures for childbirth as recommended by WHO, Gull’s sister was given no such clinical care.

Mr. Raheem, President of the Paramedic Association of Loralai, recalls “Back in winter 2020, I remember that it was snowing and a similar emergency case arrived at the hospital. In absence of operating staff, they were told to rush to capital city Quetta. Think about it! What would have been that patient’s condition? She could have lost her life.”

Dostain Jamaldini, Secretary Health for Balochistan, describes how the system currently works:

“The ministry for health has facilitated Basic Health Units and Rural Health Units (BHUs/RHUs), as well as district headquarter hospitals. Primary clinical support is given initially at the basic level at BHUs and secondary services such as surgery, transplants and other major operations at central hospitals in district capitals.”

He continues:

“Talking of the case that was reported on July 10, of Teaching Hospital Loralai: indeed such occurrences take place, but they are few in number. The health department keeps trying to ensure better healthcare for the people of Balochistan. But it also tries to address the inner mismanagement, dysfunctionality and departmental errors, because this is a matter of human survival. We cannot take risks by providing no initial clinical support.”

Yet, in Pakistan, the absence of clinical support results in misery in far too many cases. Experts say that only increased fiscal outlays can help provide the healthcare facilities needed by Pakistan's citizens.