On December 14, 2018, Prime Minister Imran Khan uploaded two short videos of eminent Islamic scholar Dr Israr Ahmed. I am not quite sure which year the videos are from, but they were obviously at least eight years old since Dr Ahmed passed away in 2010.

In one of the videos, Dr Ahmed quotes an excerpt from a diary written by Dr Riaz Ali Shah who was a physician of Pakistan’s founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, when the latter was suffering from tuberculosis. Jinnah passed away in September 1948.

In the video, Dr Ahmed informs his audience that he had picked the excerpt from an article published in a September 1988 edition of the Urdu daily Jang — 40 years after Jinnah’s demise.

Dr Ahmed quotes the 1988 newspaper article about Dr Riaz Ali’s ‘diary’ in which he writes that as Jinnah lay on his bed suffering from tuberculosis, he (Jinnah) spoke about his vision of a Pakistan that would be an Islamic state or the 20th-century manifestation of a state constructed during the rule of Islam’s first four caliphs (Khilafat-i-Rashida).

Dr Riaz was one of the four doctors present during Jinnah’s last hours. According to an article in the Pulse Fortnightly written by Lt Gen (Rtd) M. Ahmad Akhtar and published on November 1, 2014, four physicians accompanied Jinnah when he travelled to the vacation resort of Ziarat in Balochistan. They were: Dr M. Ali Mistri, Dr Illahi Bakhsh, Dr Ghulam Muhammad and Dr Riaz Ali Shah. Dr Mistri was Jinnah’s personal physician who, according to Lt Gen Akhtar, had moved to Karachi from Bombay on Jinnah’s request after the creation of Pakistan.

Nothing was reported about Jinnah’s ‘last words’ as such until the appearance of a book in 1978 by Dr Illahi Bakhsh, which was re-printed by the Oxford University Press in 2012. Dr Illahi’s book With the Quaid-i-Azam in His Last Days is largely a detailed account of the Quaid’s illness and how Jinnah tried to live with it. There is nothing in the book about an ill man lucidly advocating the creation of an Islamic state.

There is also a PDF copy available online of an Urdu translation of Dr Illahi Bakhsh’s book. However, attached to it is an Urdu translation of notes supposedly kept by Dr Riaz Ali Shah in a diary.

The notes appear in the shape of a booklet called Quaid-i-Azam Kay Akhri Lamhaat (The Quaid’s Last Moments). The booklet does not mention the date of publication. It is not available in any of the major bookstores in Pakistan nor on Amazon; neither is it mentioned in the long list of books and papers on Jinnah that appear on the Government of Pakistan’s website dedicated to the study of Pakistan’s founder.

In a 2003 article for The Concept, Raja A. Khan writes that the booklet by Dr Shah was published in 1950. However, Raja only speaks about Jinnah sharing his views on Kashmir with Riaz. One wonders, though, how many diverse topics the founder was discussing with the good doctor during his very last moments.

What is more important is that after going through the online version of the booklet, I found no mention of Jinnah speaking to Dr Shah about the caliphate.

The booklet is only scarcely referenced in the papers and books written on Jinnah. Moreover, whenever it is, as in Masud-ul-Hasan’s Anecdotes of Quaid-i-Azam (1976), it simply quotes Riaz as saying that Jinnah’s last spoken words were, “Allah, Pakistan.”

Therefore, PM Khan may have gotten a tad too excited after coming across the mentioned clip of Dr Ahmed. Without much thought, the PM used it the same manner in which Jinnah was concocted by the Gen Zia dictatorship in the 1980s.

The confusion in this respect is rooted in what transpired during the Zia regime. For example, only quotes of Jinnah that had the word ‘Islam’ in them were allowed to be used in state-owned media.

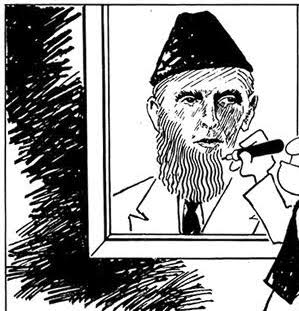

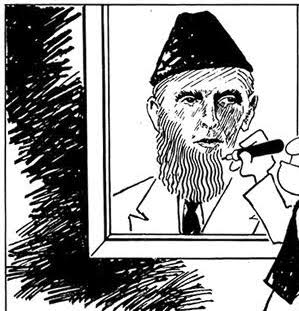

From 1978 onward, the sequence of words of Jinnah’s motto, “Unity, Faith, Discipline” was switched to “faith, unity, discipline.” In 1982, a portrait of Jinnah painted by artist Ahmad S. Nagi was replaced in the waiting lounge of the Karachi Airport just because it showed Jinnah wearing a suit and a tie.

An article on Nagi that appeared in the September 2, 2006 edition of Dawn says that the painting was finished in 1944 and then brought to Karachi after the creation of Pakistan. It was placed in the airport lounge but replaced in 1982 with another portrait of Jinnah in which he is seen wearing a sherwani.

Then in 1983, the Zia regime gleefully announced the ‘discovery’ of a diary kept by the founder in which he had expressed his desire for an Islamic state. K.K. Thomas, in the 1998 issue of Asian Recorder, and author Khaled Ahmed in his 2001 book Pakistan: Behind the Ideology Mask, write that the state-owned media enthusiastically began discussing the contents of the so-called diary.

According to Ahmad, Jinnah’s personal secretary, K.H. Khursheed, and veteran Muslim Leaguer, Mumtaz Daultana, challenged the discovery. Consequently, the claim was quietly dropped. Most interesting is the similarity between what Zia claimed Jinnah wrote in his diary and what Dr Ahmed claimed Dr Riaz wrote in his. One can thus conclude that maybe a third party was involved who, for political reasons, concurrently ascribed the mentioned quotes to Jinnah as well as Dr Riaz.

Now consider this: The day after the celebrated Turkish nationalist and founder of the modern Turkish republic, Kamal Ataturk, passed away in November 1939, one of the leading Urdu dailies in pre-Partition India, the Inqilab, reported that Ataturk, who had slipped into a coma before his death, “briefly woke up to convey a message to a servant of his.”

Apparently, the staunch, life-long secularist who went the whole nine yards during his long rule to erase all cultural and political expressions associated with Turkey’s caliphate past, had briefly woken up from a coma to instruct his servant to tell the ‘millat-i-Islamiyya’ to follow on the footsteps of the Khulfa-i-Rashideen.

Inqilab was a respected Urdu daily catering to the urban Muslim middle classes in pre-Partition India. In its November 11, 1939 issue, the paper went on to ‘report’ that Ataturk, after communicating his message to the servant, shouted “Allah is great!” and passed away. This time forever.

So why does this happen? One rather convincing way of finding an answer to this question can be ascertained from historian Dr Markus Daechsel’s 2002 study of India and Pakistan’s urban middle-class milieu. Even though a part of his study was focused on the history of fantastical claims of this nature, made by the Hindus and Muslims of the subcontinent, the tools that he used to explain such behaviour can be applied universally.

According to Daechsel, people who are not happy with ‘empirical reality’ create a ‘conceptual reality’. Empirical reality is the reality which one interacts with on a daily basis. The conceptual reality, on the other hand, is created and fuelled by certain firmly-held ideological drivers or by what one thinks empirical reality should actually be.

Conceptual reality is an imagined world but it is stuffed with claims and physical paraphernalia to make it seem like empirical reality. Daechsel writes that such claims can include the projection of one’s religious and ideological beliefs on people that have little or nothing to do with them.

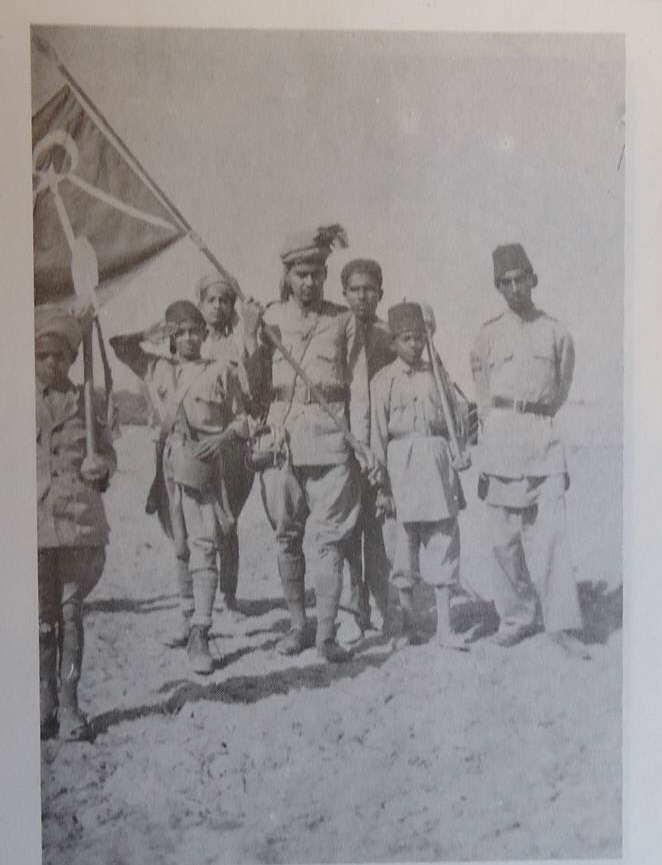

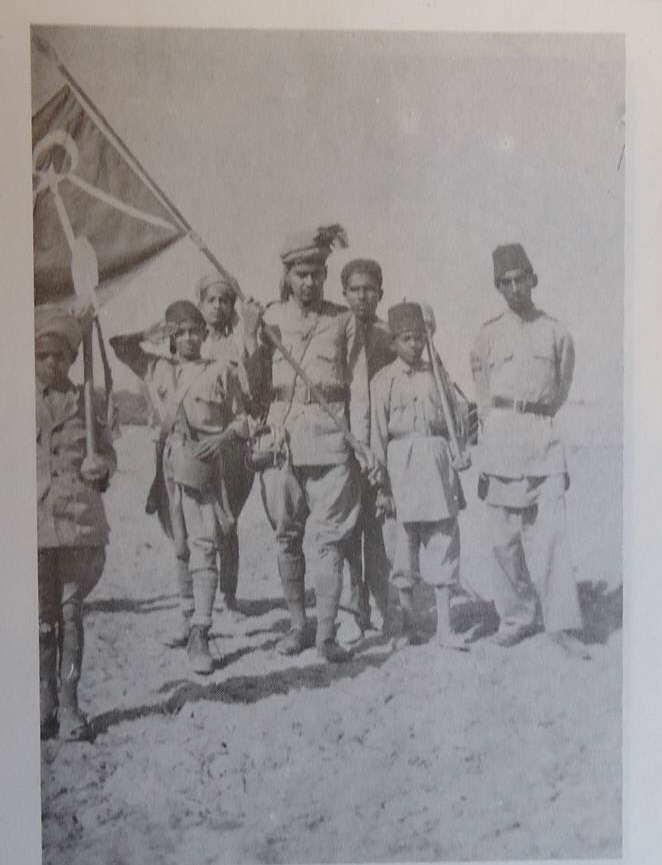

Such projections, which are often proliferated through populist media, try to concretise conceptual reality. In another interesting example, Daechsel writes that certain pre-Partition Muslim and Hindu groups insisted that their members wear a uniform and hold parades. Daechsel writes that in the empirical reality, there was no war or revolution taking place. But in the minds of the members of the outfits, there was (or should have been). So they created a conceptual reality in which there was revolutionary turmoil and these outfits were an integral part of it.

Daechsel also gives the example in which Hindus and Muslims after feeling unable to challenge Western inventions and economics in the empirical reality, created a conceptual reality by claiming that whatever the West had achieved in the fields of science had already been achieved by ancient Hindus and/or is already present in Islam.

The projection bit in Daechsel’s study is most intriguing. It might explain why some journalists, ideologues, and politicians decided to ascribe some rather unlikely words to Jinnah and Ataturk as they lay dying. It was conceptual reality coming into play to counter the empirical reality in which Jinnah and Ataturk had done no such thing.

Quite clearly, unable to come to terms with Ataturk and Jinnah’s modernist dispositions in the empirical reality, some created a conceptual reality in which, in death, both dramatically became caliphate enthusiasts.

Even to this day, many continue to excitedly share Dr. Israr’s video on social media. The whole idea of conceptual reality trying to overshadow empirical reality can also be understood through the following examples.

Sometime in the late 1970s, tabloids in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Egypt carried front-page news about Neil Armstrong — the famous American astronaut who, in 1969, became the first man to walk on the moon.

The news claimed that Armstrong had converted to Islam. Supposedly he had done so after confessing that when he was on the moon, he had heard the sound of the azaan, the Muslim call to prayer.

J.R. Hensen, in his 2006 biography of Armstrong, First Man, writes that by 1980 the news had been repeatedly carried and reproduced by tabloids in a number of other Muslim-majority countries as well. So much so, that Armstrong began receiving invitations from Islamic organisations in many Muslim countries and from within the US.

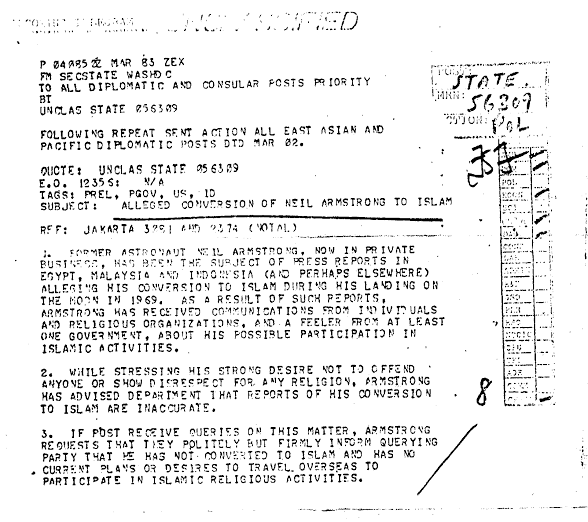

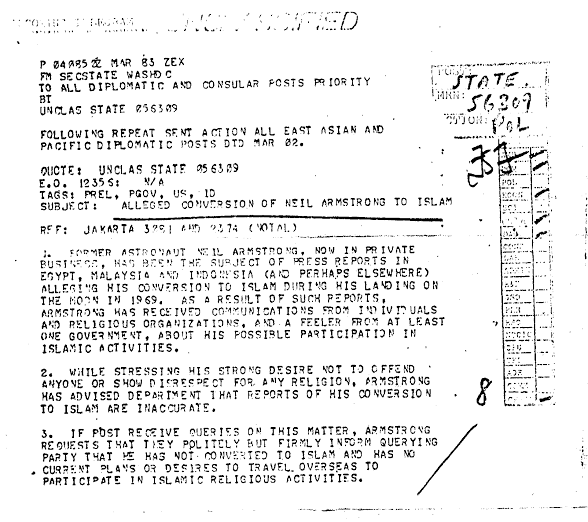

The news continued to gather momentum in Muslim countries. Hensen writes that in 1983, on Armstrong’s request, the US State Department issued instructions to US embassies in Muslim countries asking them to ‘politely but firmly’ communicate that Armstrong had not converted to Islam and that “he had no current plans or desire to travel overseas to participate in Islamic activities.”

Despite this, the belief that he had converted to Islam after hearing the azaan on the moon continued to do the rounds. In fact, this impression still pops up on YouTube channels and websites funded and run by various Islamic evangelical organisations.

Hensen suggests that the Muslims who had first initiated the ‘news’ of Armstrong’s alleged conversion might have been influenced by the claims of some American Christian organisations. A few days after Armstrong’s moon landing in 1969, these organisations had announced that “God had put Armstrong on the moon to show God’s greatness in a new light.” They nonchalantly assumed that the extremely private Armstrong was a practicing Christian.

The late pop sensation Michael Jackson, too, was said to have “converted to Islam” just before his death in 2009. What’s more, an MP3 recording of a naat, supposedly recited by Jackson, began to circulate on social media. Clearly the reciter was not Jackson, but this did not stop many across the Muslim world to believe otherwise.

In one of the videos, Dr Ahmed quotes an excerpt from a diary written by Dr Riaz Ali Shah who was a physician of Pakistan’s founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, when the latter was suffering from tuberculosis. Jinnah passed away in September 1948.

In the video, Dr Ahmed informs his audience that he had picked the excerpt from an article published in a September 1988 edition of the Urdu daily Jang — 40 years after Jinnah’s demise.

Dr Ahmed quotes the 1988 newspaper article about Dr Riaz Ali’s ‘diary’ in which he writes that as Jinnah lay on his bed suffering from tuberculosis, he (Jinnah) spoke about his vision of a Pakistan that would be an Islamic state or the 20th-century manifestation of a state constructed during the rule of Islam’s first four caliphs (Khilafat-i-Rashida).

Dr Riaz was one of the four doctors present during Jinnah’s last hours. According to an article in the Pulse Fortnightly written by Lt Gen (Rtd) M. Ahmad Akhtar and published on November 1, 2014, four physicians accompanied Jinnah when he travelled to the vacation resort of Ziarat in Balochistan. They were: Dr M. Ali Mistri, Dr Illahi Bakhsh, Dr Ghulam Muhammad and Dr Riaz Ali Shah. Dr Mistri was Jinnah’s personal physician who, according to Lt Gen Akhtar, had moved to Karachi from Bombay on Jinnah’s request after the creation of Pakistan.

Nothing was reported about Jinnah’s ‘last words’ as such until the appearance of a book in 1978 by Dr Illahi Bakhsh, which was re-printed by the Oxford University Press in 2012. Dr Illahi’s book With the Quaid-i-Azam in His Last Days is largely a detailed account of the Quaid’s illness and how Jinnah tried to live with it. There is nothing in the book about an ill man lucidly advocating the creation of an Islamic state.

There is also a PDF copy available online of an Urdu translation of Dr Illahi Bakhsh’s book. However, attached to it is an Urdu translation of notes supposedly kept by Dr Riaz Ali Shah in a diary.

The notes appear in the shape of a booklet called Quaid-i-Azam Kay Akhri Lamhaat (The Quaid’s Last Moments). The booklet does not mention the date of publication. It is not available in any of the major bookstores in Pakistan nor on Amazon; neither is it mentioned in the long list of books and papers on Jinnah that appear on the Government of Pakistan’s website dedicated to the study of Pakistan’s founder.

In a 2003 article for The Concept, Raja A. Khan writes that the booklet by Dr Shah was published in 1950. However, Raja only speaks about Jinnah sharing his views on Kashmir with Riaz. One wonders, though, how many diverse topics the founder was discussing with the good doctor during his very last moments.

What is more important is that after going through the online version of the booklet, I found no mention of Jinnah speaking to Dr Shah about the caliphate.

The booklet is only scarcely referenced in the papers and books written on Jinnah. Moreover, whenever it is, as in Masud-ul-Hasan’s Anecdotes of Quaid-i-Azam (1976), it simply quotes Riaz as saying that Jinnah’s last spoken words were, “Allah, Pakistan.”

Therefore, PM Khan may have gotten a tad too excited after coming across the mentioned clip of Dr Ahmed. Without much thought, the PM used it the same manner in which Jinnah was concocted by the Gen Zia dictatorship in the 1980s.

The confusion in this respect is rooted in what transpired during the Zia regime. For example, only quotes of Jinnah that had the word ‘Islam’ in them were allowed to be used in state-owned media.

From 1978 onward, the sequence of words of Jinnah’s motto, “Unity, Faith, Discipline” was switched to “faith, unity, discipline.” In 1982, a portrait of Jinnah painted by artist Ahmad S. Nagi was replaced in the waiting lounge of the Karachi Airport just because it showed Jinnah wearing a suit and a tie.

An article on Nagi that appeared in the September 2, 2006 edition of Dawn says that the painting was finished in 1944 and then brought to Karachi after the creation of Pakistan. It was placed in the airport lounge but replaced in 1982 with another portrait of Jinnah in which he is seen wearing a sherwani.

Then in 1983, the Zia regime gleefully announced the ‘discovery’ of a diary kept by the founder in which he had expressed his desire for an Islamic state. K.K. Thomas, in the 1998 issue of Asian Recorder, and author Khaled Ahmed in his 2001 book Pakistan: Behind the Ideology Mask, write that the state-owned media enthusiastically began discussing the contents of the so-called diary.

According to Ahmad, Jinnah’s personal secretary, K.H. Khursheed, and veteran Muslim Leaguer, Mumtaz Daultana, challenged the discovery. Consequently, the claim was quietly dropped. Most interesting is the similarity between what Zia claimed Jinnah wrote in his diary and what Dr Ahmed claimed Dr Riaz wrote in his. One can thus conclude that maybe a third party was involved who, for political reasons, concurrently ascribed the mentioned quotes to Jinnah as well as Dr Riaz.

Now consider this: The day after the celebrated Turkish nationalist and founder of the modern Turkish republic, Kamal Ataturk, passed away in November 1939, one of the leading Urdu dailies in pre-Partition India, the Inqilab, reported that Ataturk, who had slipped into a coma before his death, “briefly woke up to convey a message to a servant of his.”

Apparently, the staunch, life-long secularist who went the whole nine yards during his long rule to erase all cultural and political expressions associated with Turkey’s caliphate past, had briefly woken up from a coma to instruct his servant to tell the ‘millat-i-Islamiyya’ to follow on the footsteps of the Khulfa-i-Rashideen.

Inqilab was a respected Urdu daily catering to the urban Muslim middle classes in pre-Partition India. In its November 11, 1939 issue, the paper went on to ‘report’ that Ataturk, after communicating his message to the servant, shouted “Allah is great!” and passed away. This time forever.

So why does this happen? One rather convincing way of finding an answer to this question can be ascertained from historian Dr Markus Daechsel’s 2002 study of India and Pakistan’s urban middle-class milieu. Even though a part of his study was focused on the history of fantastical claims of this nature, made by the Hindus and Muslims of the subcontinent, the tools that he used to explain such behaviour can be applied universally.

According to Daechsel, people who are not happy with ‘empirical reality’ create a ‘conceptual reality’. Empirical reality is the reality which one interacts with on a daily basis. The conceptual reality, on the other hand, is created and fuelled by certain firmly-held ideological drivers or by what one thinks empirical reality should actually be.

Conceptual reality is an imagined world but it is stuffed with claims and physical paraphernalia to make it seem like empirical reality. Daechsel writes that such claims can include the projection of one’s religious and ideological beliefs on people that have little or nothing to do with them.

Such projections, which are often proliferated through populist media, try to concretise conceptual reality. In another interesting example, Daechsel writes that certain pre-Partition Muslim and Hindu groups insisted that their members wear a uniform and hold parades. Daechsel writes that in the empirical reality, there was no war or revolution taking place. But in the minds of the members of the outfits, there was (or should have been). So they created a conceptual reality in which there was revolutionary turmoil and these outfits were an integral part of it.

Daechsel also gives the example in which Hindus and Muslims after feeling unable to challenge Western inventions and economics in the empirical reality, created a conceptual reality by claiming that whatever the West had achieved in the fields of science had already been achieved by ancient Hindus and/or is already present in Islam.

The projection bit in Daechsel’s study is most intriguing. It might explain why some journalists, ideologues, and politicians decided to ascribe some rather unlikely words to Jinnah and Ataturk as they lay dying. It was conceptual reality coming into play to counter the empirical reality in which Jinnah and Ataturk had done no such thing.

Quite clearly, unable to come to terms with Ataturk and Jinnah’s modernist dispositions in the empirical reality, some created a conceptual reality in which, in death, both dramatically became caliphate enthusiasts.

Even to this day, many continue to excitedly share Dr. Israr’s video on social media. The whole idea of conceptual reality trying to overshadow empirical reality can also be understood through the following examples.

Sometime in the late 1970s, tabloids in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Egypt carried front-page news about Neil Armstrong — the famous American astronaut who, in 1969, became the first man to walk on the moon.

The news claimed that Armstrong had converted to Islam. Supposedly he had done so after confessing that when he was on the moon, he had heard the sound of the azaan, the Muslim call to prayer.

J.R. Hensen, in his 2006 biography of Armstrong, First Man, writes that by 1980 the news had been repeatedly carried and reproduced by tabloids in a number of other Muslim-majority countries as well. So much so, that Armstrong began receiving invitations from Islamic organisations in many Muslim countries and from within the US.

The news continued to gather momentum in Muslim countries. Hensen writes that in 1983, on Armstrong’s request, the US State Department issued instructions to US embassies in Muslim countries asking them to ‘politely but firmly’ communicate that Armstrong had not converted to Islam and that “he had no current plans or desire to travel overseas to participate in Islamic activities.”

Despite this, the belief that he had converted to Islam after hearing the azaan on the moon continued to do the rounds. In fact, this impression still pops up on YouTube channels and websites funded and run by various Islamic evangelical organisations.

Hensen suggests that the Muslims who had first initiated the ‘news’ of Armstrong’s alleged conversion might have been influenced by the claims of some American Christian organisations. A few days after Armstrong’s moon landing in 1969, these organisations had announced that “God had put Armstrong on the moon to show God’s greatness in a new light.” They nonchalantly assumed that the extremely private Armstrong was a practicing Christian.

The late pop sensation Michael Jackson, too, was said to have “converted to Islam” just before his death in 2009. What’s more, an MP3 recording of a naat, supposedly recited by Jackson, began to circulate on social media. Clearly the reciter was not Jackson, but this did not stop many across the Muslim world to believe otherwise.