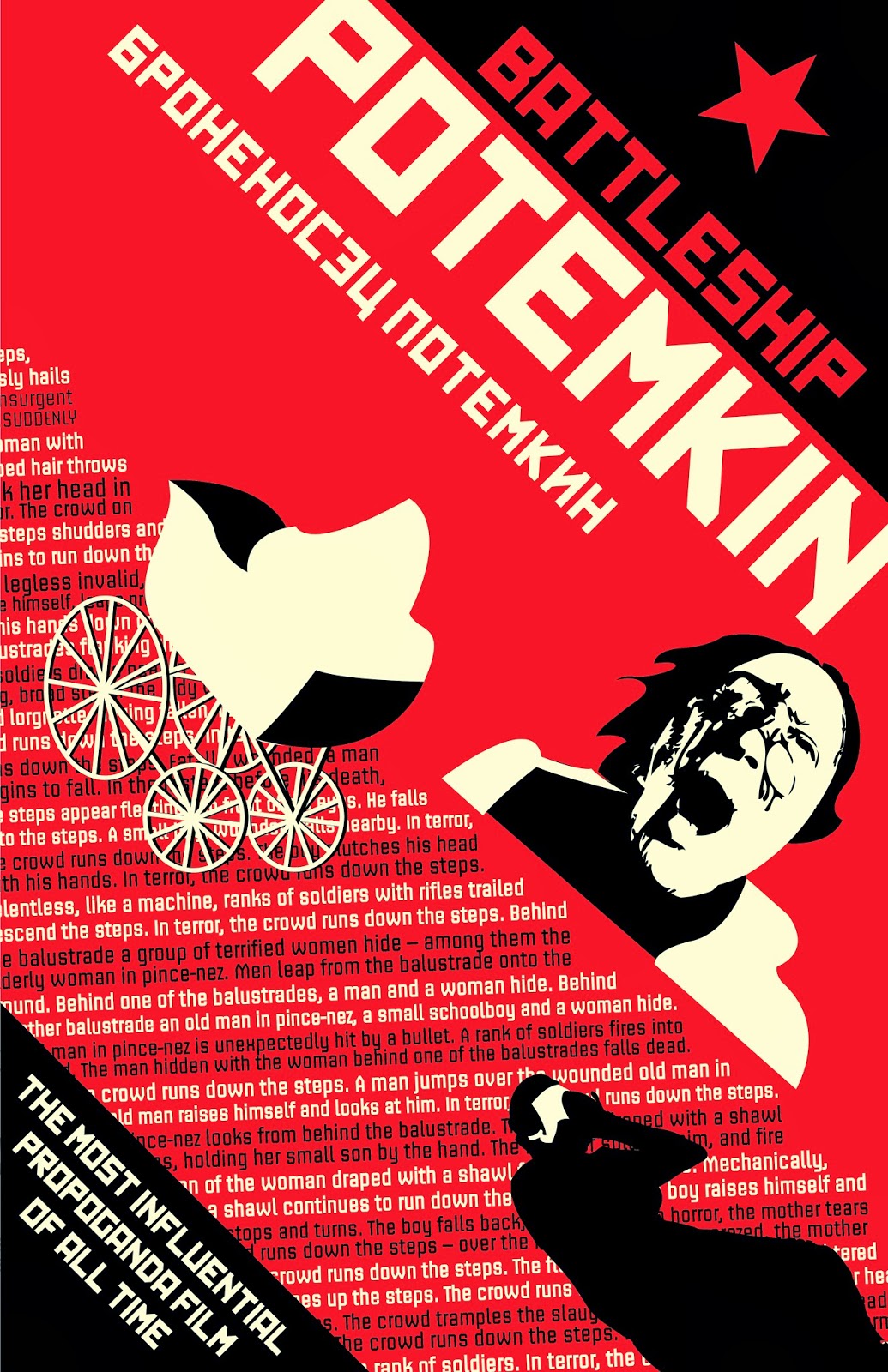

Films such as the famous Soviet director Sergel Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), which, with great mastery weaved together accomplished filmmaking and communist propaganda, are often called ‘socialist films’. This form of cinema, though not always as accomplished as Potemkin, was quite common during the Cold War (1949-90) in East Europe, Soviet Union and China.

1925’s Battleship Potemkin is one of the earliest and perhaps the finest film ever made in Socialist Cinema genre.

As interest in communism grew after the 1918 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, and then the 1949 victory of the communists in China, many filmmakers in non-communist countries, smitten by communism/socialism, too began helming films that were sympathetic towards communism and socialism.

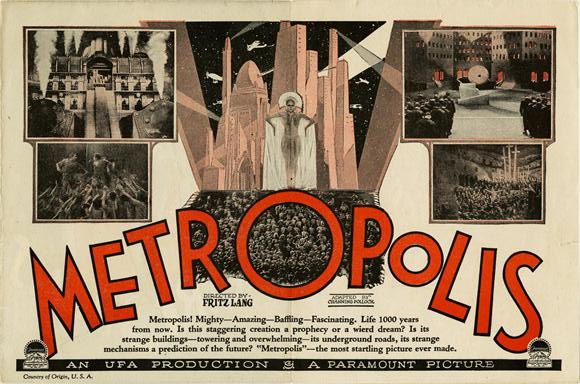

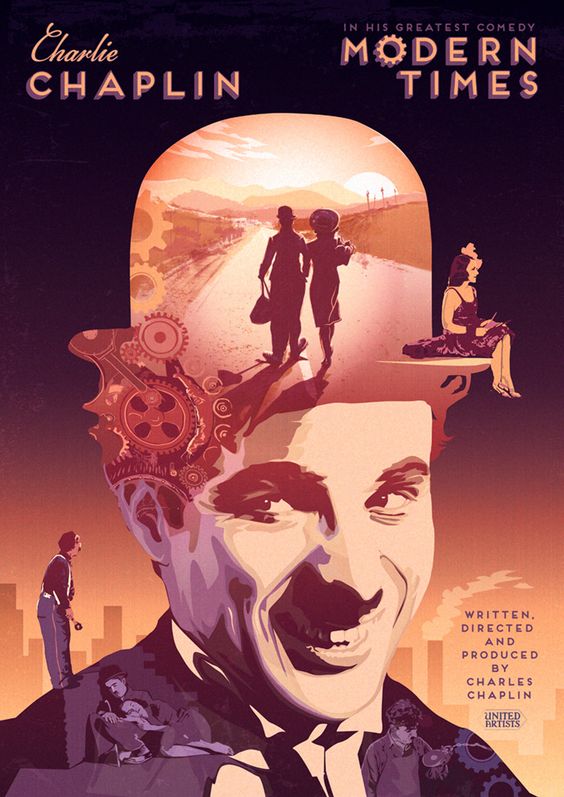

Fritz Lang’s German sci-fi classic, Metropolis (1927) and the brilliant Hollywood comedian, Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936) both used mainstream cinema and film genres (sci-fi and comedy) to attack capitalist exploitation of the workers.

Alarmed by the alleged growth of ‘socialist messages’ in Hollywood films, a fiery conservative US Senator, Joseph McCarthy, claimed that Hollywood was crawling with ‘anti-American communists and socialists.’

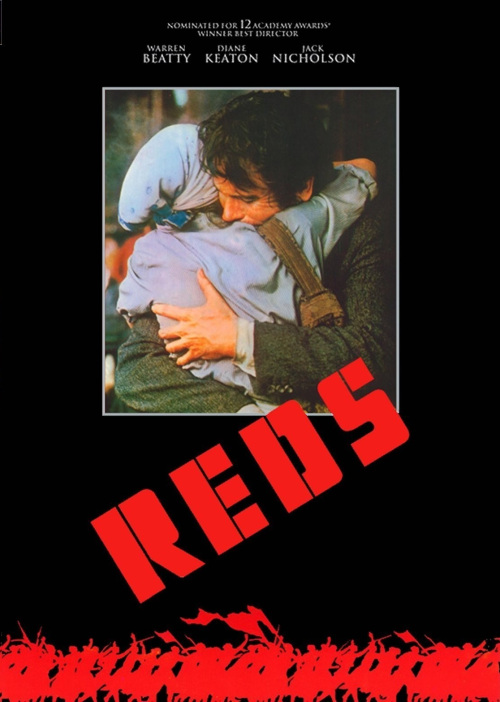

In 1947 he launched a witch hunt in the American film industry that led to the banning and black-listing of dozens of directors, producers and script-writers. Yet, even till the 1970s and the early 1980s, socialist films were slipping through the cracks. Examples range from 1973’s The Way We Were (starring Robert Redford and Barbra Streisand) and 1981’s Reds, a biopic of the American communist journalist, John Reed. Reds also managed to receive three Academy Awards (Oscars)!

In 1927 German filmmaker, Fritz Lang, used sci-fi and German Expressionism to create an industrial dystopia in which a decadent class exploits and dehumanizes the masses through mechanization.

Charlie Chaplin’s satirized capitalism and industrialization in 1937’s Modern Times. Though a huge star in Hollywood, Chaplin was a vocal sympathizer of communism. He left the US in 1951 and his re-entry to the US was halted. He settled in Switzerland. In 1972, Chaplin was invited to return to the US and awarded an honorary Academy Award.

1981’s Reds was a sympathetic biopic of communist American journalist, John Reed. It won 3 Academy Awards (Oscars).

Britain too produced some notable socialist films, such as 1941’s The Agitator, 1967’s Privilege, and 1966’s Morgan. But unlike the socialist films of the ‘communist block’, films of this genre in non-communist countries were subtler in their message and did not shy away from sometimes critiquing versions of communism propagated by the Soviet Union and Mao’s China.

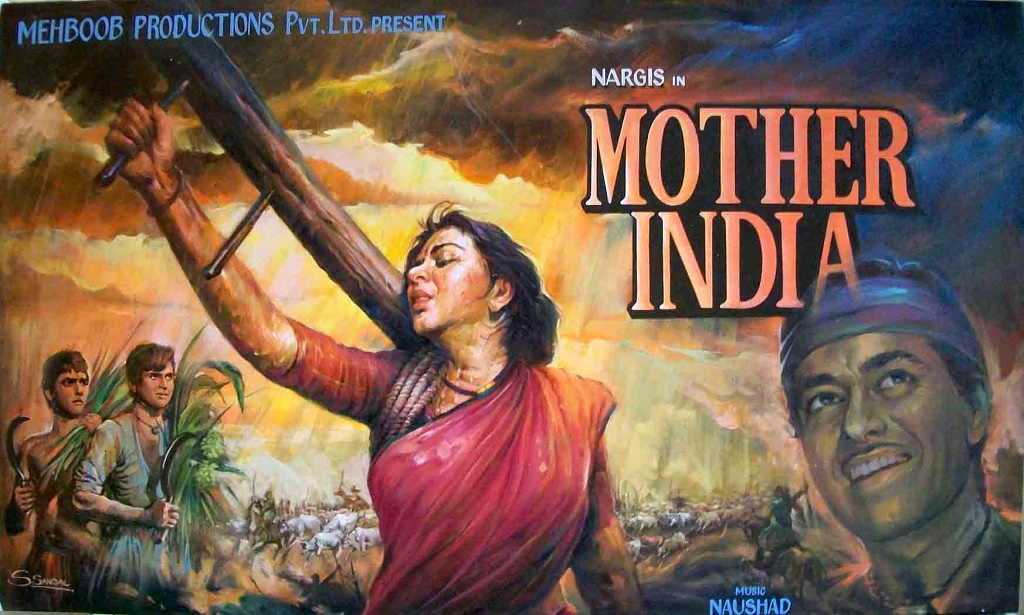

In India, both mainstream and parallel cinemas, frequently empathized with socialist sentiments. On most occasions, mainstream cinema in India weaved socialist messages with the Indian nationalist impulse. Some examples in this context include Mehboob Khan’s 1957 masterpiece, Mother India and Yash Chopra’s Kala Pathar (1977).

From the late 1970s and across much of the 1980s, India also developed a thriving ‘art film’ and/or ‘parallel cinema’ scene which produced dozens of films with somewhat overt socialist messages.

The socialist film genre withered away at the end of the Cold War in 1990; the collapse of the Soviet Union; and due to the drastic economic paradigm shift in China.

1957’s Mother India weaved socialist sentiments with India’s nationalist impulse.

1979’s Kala Pathar was based on an actual (violent) coalminers’ strike in India.

Today the Pakistan film industry is certainly exhibiting signs of a revival. The industry had begun its gradual decline in the 1980s before almost completely collapsing by the early 2000s. Yet, the current scene pales in comparison to its hay days.

According to the late film-maker, Mushtaq Gazdar’s 1997 book, Pakistan Cinema, the Pakistan film industry began witnessing a surge in the mid-1960s. It hit a commercial and creative peak in the 1970s. By 1975 the industry was producing an average of 35 to 40 films a year.

However, from 1980 onwards, its fortunes began to dwindle due to three factors: 1) Creative complacency within the industry; 2) The arrival of the VCR which saw the invasion of bootlegged Indian films; and 3) the stern censor policies of the dictatorship of General Zia-ul-Haq who came to power through a reactionary military coup in July 1977.

Even though most films in India and Pakistan (in the 1960s and 1970s) largely invested in producing one-dimensional romantic farces, there were also films with plots and sub-plots that addressed more ‘social issues.’ However, the love story formula remained to be the overarching theme.

But in India which had adopted a South Asian version of democratic-socialism (also called ‘Nehruvian socialism’) right from the onset, its film industry was quick to also offer filmic samples of this socialism. There are numerous examples in this context that have been extensively analyzed by Indian as well as western film historians.

Yet, no such analysis are available on Pakistan’s Socialist Cinema. This is mainly because there were far less socialist films produced in Pakistan than in India. The memory of such films ever being made in Pakistan evaporated rather quickly.

Pakistan did not adopt ‘socialism’ till the 1970s. Between its birth in 1947 and the arrival of a socialist regime in 1971, Pakistan was largely a capitalist country whose state treated socialism as an enemy. Socialism again became an enemy after 1977 before its international demise in the 1990s.

But fact is, Pakistan film industry did manage to produce a handful of socialist films before the industry’s collapse.

Jago Hua Savera (1959)

Helmed by the auteur director, AJ Kardar, Jago Hua Savera was released in 1959. It was scripted by the famous progressive Urdu poet, Faiz Ahmad Faiz, who also wrote the lyrics for the film’s songs. Based on a novel by a Bengali author, the film takes place in a fishing village of former East Pakistan where impoverished fishing families battle poverty, loan sharks and petty capitalist exploiters on a daily basis.

Inspired by ‘socialist realism’ and ‘Italian neo-realism,’ there is nothing exaggerated in Jago. It portrays a fisherman and his family’s struggles in a realist manner, brilliantly captured by the famous British cameraman, Walter Lassally. Jagu can also be called, Pakistan’s first ‘art film’.

The film was released just a year after Pakistan’s then military chief, Ayub Khan, imposed the country’s first Martial Law. Khan was not only a harsh critic of the religious parties, he was equally allergic to socialism, terming the country’s leftist politicians and intelligentsia as ‘reckless adventurers,’ as he launched his government’s ambitious industrialization process.

Faiz was in jail when the film was released. It went through numerous recuts ‘advised’ by the censors, until it completely vanished from the cinemas. It was nominated for an Oscar, though, becoming Pakistan’s first film to be nominated in the Best Foreign Language Film category.

A still from Jago Hua Savera

The film was scripted by the famous progressive poet, Faiz Ahmad Faiz.

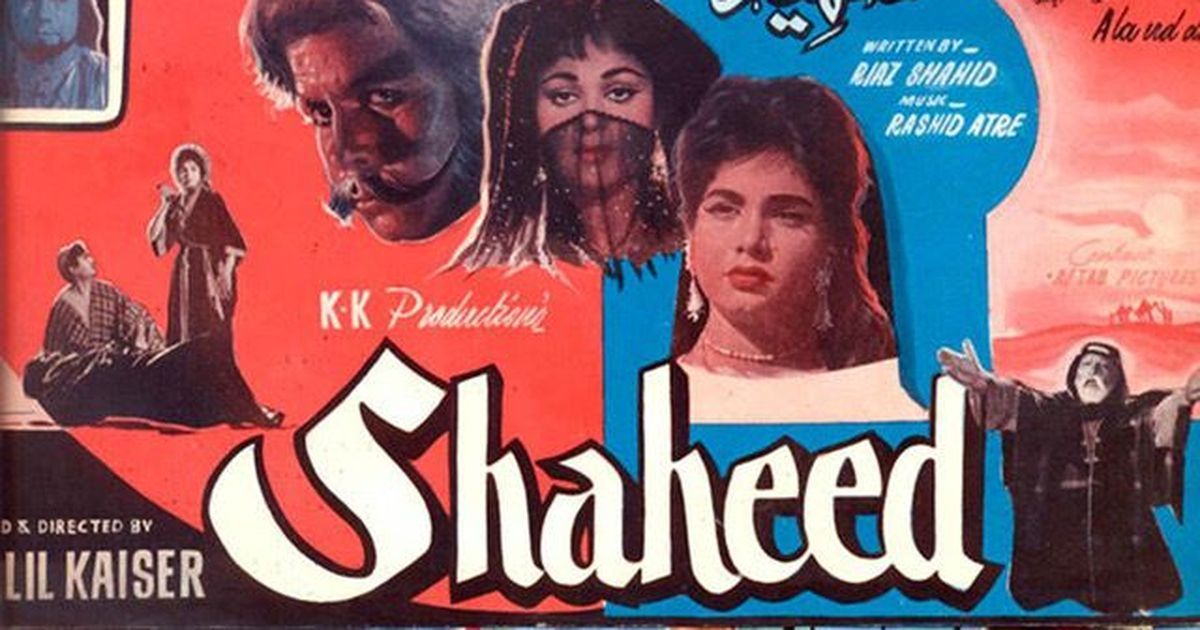

Shaheed (1962)

During the height of the Ayub Khan regime, director Khalil Kaiser and writer Riaz Shahid managed to helm a mainstream Urdu film which glorified revolutionary socialism. Aware of the Ayub regime’s aversion to socialism, Shahid penned a story which takes place in an Arab country which is being led by a tribal chieftain.

Shahid was close to progressive poets, Faiz Ahmad Faiz and Munir Niazi. Both were hired to pen the songs for the film. Due to his friendship with Faiz, Shahid had become an admirer of then Egyptian president, Gamal Abdel Nasser, who at the time was the most influential leader in the Muslim world.

Nasser, a military officer, had overthrown the pro-British Egyptian monarchy in 1952. He then adopted what became to be known as ‘Arab Socialism’. Arab Socialism was a fusion of Arab nationalism and socialism. Nasser brought Egypt into the orbit of the Soviet Union and began to financially, politically and militarily support left-wing Arab nationalist movements in various Arab countries.

Nasser also became a passionate adversary of Arab monarchies, especially the one in Saudi Arabia. Nasser accused them of being ‘decadent’ and ‘agents of western capitalism.’

Shaheed clearly tips its hat to Arab Socialism. The film takes place in an oil-rich Arab country in which a British man, Lawrence, engineers the fall of its compassionate chieftain and replaces him with a corrupt and decadent ruler. He also proliferates the use of opium in the society, so that Lawrence’s business of exporting the country’s oil to the west is not challenged.

However, a poor blacksmith who has become a revolutionary joins hands with the exiled chieftain and both begin to organize a peoples uprising against the new ruler and Lawrence.

The film did cause some concern in the Ayub regime, but it was allowed to play to packed houses. Some complaints against the film were also lodged by the Saudi Embassy in Pakistan, but in those days the Saudis hardly had any influence in Pakistan.

A still from the movie Shaheed

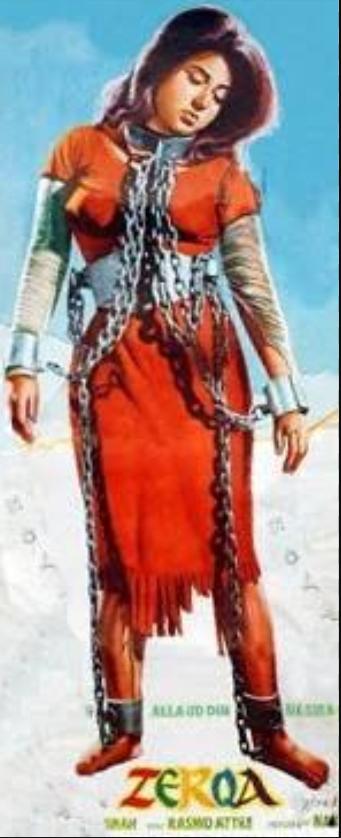

Zarqa (1969)

In March 1969, a students and labour movement forced Ayub Khan to resign. He was replaced by General Yahya Khan who promised to hold Pakistan’s first election based on adult franchise. Revolutionary fervor had gripped the youth of West and East Pakistan, and Riaz Shahid by now had become an established director.

He wanted to encapsulate the zeitgeist of an era in which students were rising against the old order across the world. Shahid was still passionately invested in Arab Socialism (which had already arrived in Pakistan in the shape of the Pakistan Peoples Party’s ‘Islamic Socialism’). Shahid had also been smitten by the celebrated Palestinian radical, Laila Khalid. So he decided to direct a film about the Palestinian struggle against Israel and use it as a metaphor to comment on what was taking place in Pakistan.

For Zarqa he used the popular communist poet, Habib Jalib, to write the songs. The central character of the film is a Palestinian woman, Zarqa, played by actress Neelo. The film is a symbolic but frontal attack on ‘imperialism’ fueled by capitalism. It became a massive hit.

A scene from Zarqa. Neelo played a character which was inspired by the Palestinian fighter, Laila Khalid.

Laila Khalid in 1970

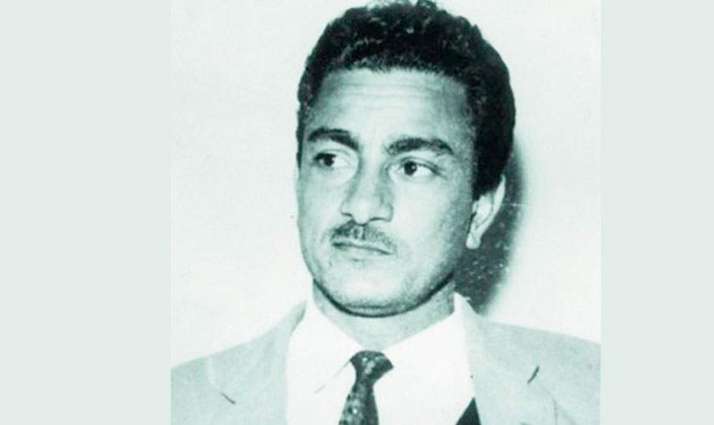

Riaz Shahid. He passed away in 1972. He was just 42.

Matti Kay Putley (1974)

Produced by the time’s famous film star, Nadeem Baig, Mitti Ke Putley was the star’s first foray into political and art-film territory. The film was inspired by the 1972 labour movement in Karachi. The movement was triggered by the campaigns of ZA Bhutto’s PPP which was being passionately supported by left-wing student groups and labour unions.

However, things between the PPP and the unions came apart when Bhutto came to power in December, 1971. Even though he introduced some radical labour policies, the unions were not satisfied and went on strike, mainly in Karachi that had been heavily industrialized during the Ayub regime in the 1960s.

The Bhutto regime crushed the movement, lamenting that the unions were hell-bent on creating problems despite the government’s favorable labour policies. In the film, Nadeem plays the son of an influential industrialist. Nadeem’s character returns from England where had gone for higher studies.

On his return he discovers that his father had been mistreating the workers of his factory. Throughout the film, the son is seen trying to resolve various complex issues emitting from his compassionate disposition in a cynical world. He sympathizes with the labour unions and tries to show them that he was not like his father. But in doing so, he is confronted by the father who thinks he is being naïve. His girlfriend too is not all that enthusiastic about his new-found pro-workers attitude.

But he fails on all three fronts when the situation becomes so bad that the workers decide to attack and burn down the factory. His only success arrives when he convinces them that by doing this, they would only be harming their own interests.

Mitti Kay Putle was not the kind of a hit Nadeem was used to. It quickly vanished from the cinemas.

Nadeem Baig

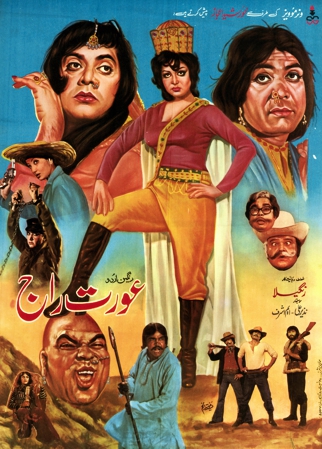

Aurat Raj (1979)

The ‘New Left’ movement that had emerged in the West in the 1960s and had critiqued Soviet and Chinese communism, formed a contemporary democratic-socialism that largely inspired various left-wing youth and social movements in the late 1960s. The social movements in this context also inspired the revolutionary ‘Women’s Liberation’ movements of the 1970s.

In 1978, famous comedian and actor, Rangeela, signed on a number of the time’s famous actors and actresses for an ambitious cinematic project. A film called Aurat Raj. The distributers were shocked at what they saw: A scathing satire on male-dominated societies. The film also parodied the concept of heroes and heroines in Pakistani films and was entirely sympathetic to the feminist point of view.

The film is actually like no other ever made in this country. It sees a repressed housewife (played by Rani) of a flamboyant male chauvinist (played by Waheed Murad) — a man who treats women like objects.

The wife finally puts her foot down and organises a women’s movement in the area. The movement dramatically spreads and mobs of women begin to get hold of oppressive men and beat them up in the streets. The government intervenes and decides to hold an election to resolve the issue. The election is swept by the Aurat Raj Party and the women gain political power. Rani becomes the country’s new leader and aquires a special bomb from a foreign country. The bomb is special because after exploding it turns all men into women!

All the women are elevated to the domestic, social and political positions that were once dominated by the males, and the men are relegated to wearing women’s clothes and pushed into occupations and duties that are stereotypically associated with women.

What follows is a hilarious, biting satire that attacks male chauvinism, social conservatism and female stereotypes constructed by the popular media in a patriarchal society.

The film was so visually and conceptually startling (for its time) that the audiences were not sure exactly how to respond. Even the censors, now under the reactionary Zia-ul-Haq dictatorship didn’t know what had it them. The film flopped but today it is considered a ‘cult classic.’

Stills from Aurat Raj

Aurat Raj