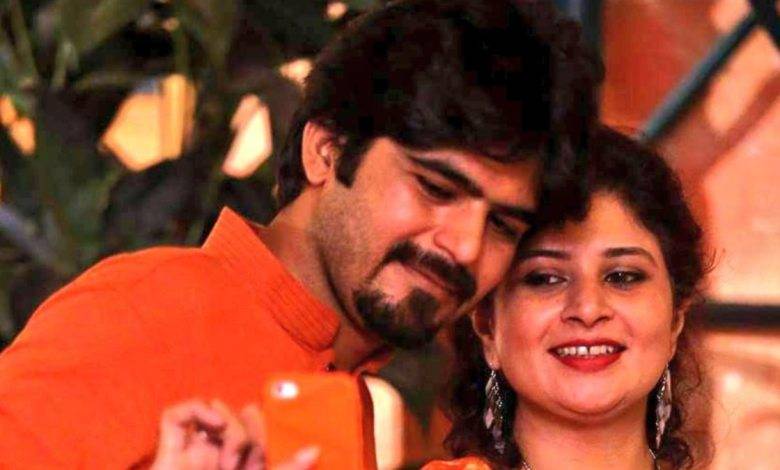

On 19 August 2018, Mudassar Mehmood Naaru went on vacation to Kaghan with his wife, Sadaf, and then six-month-old son, Sachal. The next morning, Mudassar and his family went to a friend’s land, where they all sat together by the river, enjoying a cup of tea. There was a waterfall in front of the river by which they were seated and Mudassar wished to go explore it. This was the last time Sadaf and Sachal saw Mudassar because after he left to go see the waterfall, he never returned.

After attempting to search for him in the locality, Mudassar’s family approached the local police station for registration of an FIR. From the time the police station was approached, local law enforcement had already made up its mind: Mudassar had drowned. As a result, their search efforts were limited to the area of the river only. They did not actually search the entire locality to try to trace Mudassar. As they believed he had drowned, although there was no evidence for the same, the police refused to register an FIR for abduction.

In October 2018, Mudassar’s father, Rana Mehmood Ikram, approached the Commission for the Inquiry of Enforced Disappearances, a body that should perhaps be disbanded as it has yet to identify, in any case before it, a single perpetrator involved in this heinous crime. The Commission directed registration of an FIR, which was finally registered on 22 November.

At least seven hearings have taken place before the Commission, from November 2018 to November 2020. Despite two years of hearings, the Commission has been unable to ascertain the fate and whereabouts of Mudassar Naaru. Mudassar’s father accordingly approached the Islamabad High Court, by filing a writ petition through the Pakistan Bar Council’s Journalist Defence Committee.

That during the course of proceedings before the High Court, the conduct of the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Defense was a nauseating mix of apathy and incompetence. The Ministry of Defence deemed the one paragraph reply it submitted to a writ petition adequate. In other words, it was more than enough for the Ministry of Defence to say Mudassar is not in the custody of the ISI or the MI. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Interior pushed the narrative that this was not a case of enforced disappearance: that Mudassar had just “willfully” disappeared.

Perhaps even more deplorable than the conduct of the Ministry of Defense and Ministry of Interior was the report submitted in Court on behalf of the Commission mainly because this Commission was ostensibly formed to help in resolution of cases of enforced disappearances. The report illustrates how powerless and useless this Commission is as it helplessly continues to state: “Reps of ISI and MI are available who have been directed once again to look into the allegation and submit replies before the next date of hearing.” And the response that keeps coming from the ISI and MI is: “we don’t have him.” In what civilized part of the world would that suffice when our intelligence agencies are constantly monitoring whereabouts and activities of journalists, lawyers, and those they deem to be “threats”? Surely, these same intelligence agencies have the capability to trace a citizen of this country, especially when said tracing would also clear their name as they keep insisting he is not in their custody.

On 17 June this year, Mudassar’s mother and Sachal came to the Islamabad High Court to attend the proceedings. Grandmother and grandson were seated right next to me in Court and I heard Sachal asking his dadi: “dado hum idher kiya kernay aaye hai?” (why are we here?). His grandmother replied softly: “hum uncle sey baat kernay aaye hai” (we are here to speak to uncle). Sachal and his grandmother were asked not once but twice to leave the courtroom by police despite the fact that Sachal, being a three-year-old child, was actually on very good behaviour.

After the hearing, my colleague and I spent some time speaking to Mudassar’s mother and to Sachal. I spent most of that time playing with Sachal’s cheeks and asking him what he liked to eat. During this time, journalist, Asad Toor, had come to cover the case and brought with him a pack of chocolates for Sachal. Sachal was so excited to eat the chocolates as we all sat in the bar room.

I have not been able to get Sachal’s face out of my mind since 17 June and I don’t think I’ll be able to forget the pain in his grandmother’s eyes for the rest of my life.

Mudassar’s mother is a strong and graceful lady. She does not deserve what she is going through. Her main concern remains when her son will return because she does not know how long she will be in this world for. She kept saying to me that she just wants him to come back so she can rest in peace knowing her grandson is being taken care of.

Mudassar’s wife, Sadaf, passed away on 9 May. She was meant to address the United Nations on 20 May and there is reason to believe her death was not of natural causes. She had been threatened on 28 January 2019, when unknown persons visited her workplace, urging her to stop raising the issue of her husband’s disappearance through social media. She was told that this would “make it more difficult for him [Mudassar].” The threats did not deter her: she continued to fight for her husband till she herself was no more.

This is a tragic story regardless of any lens you look at it through. If the State has disappeared Mudassar, it is directly responsible for tearing his family apart. If Mudassar left on his own and the State has been unable to determine his fate and/or whereabouts in 3 years, it is either incompetent or apathetic – or both. If Mudassar had committed a crime, why was he not produced before a court of law? What was the fault of his now three-year-old child who, in all likelihood, does not even remember what his father looks like at this stage?

This is a crime against humanity. At best, the State is incompetent and at worst, it is complicit. Either way, there must be accountability for the same. Nothing will give Sachal his mother back and since his father’s disappearance, she was the only parent he had. Mudassar’s mother told me how Sachal is confused: sometimes he thinks his grandmother is his mother and his grandfather is his father. I couldn’t sit there listening to her without tears welling up in my eyes and my heart feeling like someone was stabbing me repeatedly. How those who are responsible for our safety and security can sleep after doing this to a living, breathing human being is beyond me. How they can continue to do so with one family after another makes one realize: their self-importance and greed is unending. Their conception of “national interest” has rendered children orphans and left families with unanswered questions that will weigh on them till they finally rest in peace.

After attempting to search for him in the locality, Mudassar’s family approached the local police station for registration of an FIR. From the time the police station was approached, local law enforcement had already made up its mind: Mudassar had drowned. As a result, their search efforts were limited to the area of the river only. They did not actually search the entire locality to try to trace Mudassar. As they believed he had drowned, although there was no evidence for the same, the police refused to register an FIR for abduction.

In October 2018, Mudassar’s father, Rana Mehmood Ikram, approached the Commission for the Inquiry of Enforced Disappearances, a body that should perhaps be disbanded as it has yet to identify, in any case before it, a single perpetrator involved in this heinous crime. The Commission directed registration of an FIR, which was finally registered on 22 November.

At least seven hearings have taken place before the Commission, from November 2018 to November 2020. Despite two years of hearings, the Commission has been unable to ascertain the fate and whereabouts of Mudassar Naaru. Mudassar’s father accordingly approached the Islamabad High Court, by filing a writ petition through the Pakistan Bar Council’s Journalist Defence Committee.

That during the course of proceedings before the High Court, the conduct of the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Defense was a nauseating mix of apathy and incompetence. The Ministry of Defence deemed the one paragraph reply it submitted to a writ petition adequate. In other words, it was more than enough for the Ministry of Defence to say Mudassar is not in the custody of the ISI or the MI. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Interior pushed the narrative that this was not a case of enforced disappearance: that Mudassar had just “willfully” disappeared.

Perhaps even more deplorable than the conduct of the Ministry of Defense and Ministry of Interior was the report submitted in Court on behalf of the Commission mainly because this Commission was ostensibly formed to help in resolution of cases of enforced disappearances. The report illustrates how powerless and useless this Commission is as it helplessly continues to state: “Reps of ISI and MI are available who have been directed once again to look into the allegation and submit replies before the next date of hearing.” And the response that keeps coming from the ISI and MI is: “we don’t have him.” In what civilized part of the world would that suffice when our intelligence agencies are constantly monitoring whereabouts and activities of journalists, lawyers, and those they deem to be “threats”? Surely, these same intelligence agencies have the capability to trace a citizen of this country, especially when said tracing would also clear their name as they keep insisting he is not in their custody.

On 17 June this year, Mudassar’s mother and Sachal came to the Islamabad High Court to attend the proceedings. Grandmother and grandson were seated right next to me in Court and I heard Sachal asking his dadi: “dado hum idher kiya kernay aaye hai?” (why are we here?). His grandmother replied softly: “hum uncle sey baat kernay aaye hai” (we are here to speak to uncle). Sachal and his grandmother were asked not once but twice to leave the courtroom by police despite the fact that Sachal, being a three-year-old child, was actually on very good behaviour.

After the hearing, my colleague and I spent some time speaking to Mudassar’s mother and to Sachal. I spent most of that time playing with Sachal’s cheeks and asking him what he liked to eat. During this time, journalist, Asad Toor, had come to cover the case and brought with him a pack of chocolates for Sachal. Sachal was so excited to eat the chocolates as we all sat in the bar room.

I have not been able to get Sachal’s face out of my mind since 17 June and I don’t think I’ll be able to forget the pain in his grandmother’s eyes for the rest of my life.

Mudassar’s mother is a strong and graceful lady. She does not deserve what she is going through. Her main concern remains when her son will return because she does not know how long she will be in this world for. She kept saying to me that she just wants him to come back so she can rest in peace knowing her grandson is being taken care of.

Mudassar’s wife, Sadaf, passed away on 9 May. She was meant to address the United Nations on 20 May and there is reason to believe her death was not of natural causes. She had been threatened on 28 January 2019, when unknown persons visited her workplace, urging her to stop raising the issue of her husband’s disappearance through social media. She was told that this would “make it more difficult for him [Mudassar].” The threats did not deter her: she continued to fight for her husband till she herself was no more.

This is a tragic story regardless of any lens you look at it through. If the State has disappeared Mudassar, it is directly responsible for tearing his family apart. If Mudassar left on his own and the State has been unable to determine his fate and/or whereabouts in 3 years, it is either incompetent or apathetic – or both. If Mudassar had committed a crime, why was he not produced before a court of law? What was the fault of his now three-year-old child who, in all likelihood, does not even remember what his father looks like at this stage?

This is a crime against humanity. At best, the State is incompetent and at worst, it is complicit. Either way, there must be accountability for the same. Nothing will give Sachal his mother back and since his father’s disappearance, she was the only parent he had. Mudassar’s mother told me how Sachal is confused: sometimes he thinks his grandmother is his mother and his grandfather is his father. I couldn’t sit there listening to her without tears welling up in my eyes and my heart feeling like someone was stabbing me repeatedly. How those who are responsible for our safety and security can sleep after doing this to a living, breathing human being is beyond me. How they can continue to do so with one family after another makes one realize: their self-importance and greed is unending. Their conception of “national interest” has rendered children orphans and left families with unanswered questions that will weigh on them till they finally rest in peace.