“Choice is a great burden. The call to invent one’s life, and to do it continuously, can sound unendurable. Totalitarian regimes aim to stamp out the possibility of choice…”

Russian-American journalist Masha Gessen wrote these words in an essay they published in 2018. Their essay mainly covered the choices they had made throughout their lives starting from when their parents decided to move to the States, which was followed by their doctor telling them that they had to choose by removing their breasts or ovaries (they eventually had to remove both and then uterus too). This was followed by their eventual decision to take hormones and their decision to regrow their breasts, and the choice they made when they decided to move back to Russia and the choice they did not make when they had to leave Russia in the aftermath of 2011-12 Pussy Riots lest secret services officials come for her kids.

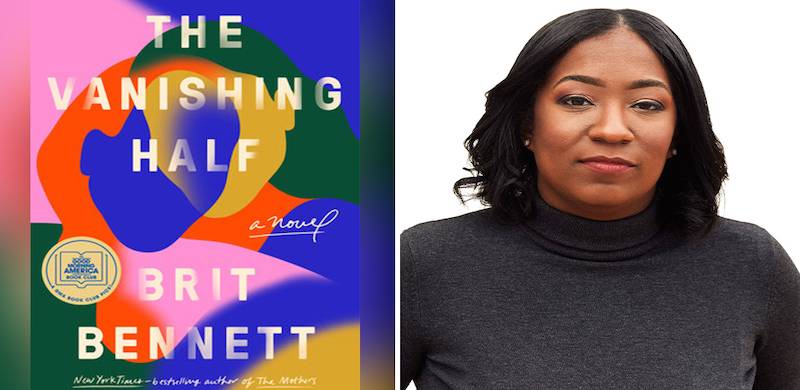

In the same vein, Brit Bennet's novel The Vanishing Half talks about choices. It talks about an awful lot of things but the choice that one of the protagonists makes—to cash in her light skin for a life where the white people would think of her as one of their own—sets the entire plot of the novel. The novel is a piece of historical fiction, released last year, set in four different time settings from 1968 to 1988, and it follows the lives of two twins born in the southern state of Louisiana in a town that one of the twin's boyfriend tried to locate on a map in vain and which is named Mallard.

The novel follows two twins named Desiree and Stella as they navigate their life when one day they run away to New Orleans leaving their light skin-obsessed hometown and their mother behind. Initially, they get along well and take on jobs to make ends meet until Stella who is much of a 'tragic mulatto' (an archetypical mixed-race person who is perpetually sad for they do not fully belong to either of the 'black' or 'white worlds') eventually decides to leave Desiree for good and start a new life with her boss leaving her a small handwritten note that says sorry. Her light skin stays loyal to her and she passes onto the white world with ease. It is unclear whether Stella derives a sense of belonging or a sense of security in the white world.

Perhaps, it is just some sort of identity incongruence that she seeks to eliminate or it is that the twins are witness to their father's tragic murder who Desiree recalls had a skin "so light that, on a cold morning, she could turn over his arm to see the blue of his veins. But none of that mattered when the white men came for him." that drives Stella to blend into a white LA so that she can stop having nightmares wherein she is being dragged out and beaten to a pulp by white men.

Stella leaving her sister for a white world sets the course of the novel and also their new generation's—Desiree's blackened and bookish daughter named Jude and Stella's hedonist and a hippie of a daughter named Kennedy—relentless quest to understand the person that was one girl's Aunt and the another's mother. Stella always found it hard to hide the lie that was her phenotype. To her daughter, she always seemed like someone she barely knew, someone who hardly ever answered her (Kennedy's) personal inquiries into her life, and someone who could hardly keep up with the facade they had chosen to embody (that they were white).

On the other hand, her seven minutes elder twin Desiree moves through her life as unsentimentally as she could. After Stella elopes, she barely knows how to do life without her. Thus, she trails back to the life in her little town with her young daughter—broken from a marriage with a man who did not love her enough to not beat her. Desiree, unlike her lost twin, makes choices that seek to amend the wrongs of her previous choices. She does not marry again even though she meets her long-lost lover who looks after her mother and brings her presents everytime he comes back from his "criminal-hunting" job.

Eventually, Jude finds her Aunt when she leaves for her studies. She even tells her cousin everything that her mother would not. There is also a homecoming when Stella goes back to see her home to see that her mother is too worn out by Alzheimer's to recollect that her daughter had returned two and a half decades later. She leaves after staying just one day without bidding farewell while the purpose of her coming is to tell Desiree to stop Jude from revealing who she was or where she belonged to Kennedy.

Brit Bennet has produced a marvelous piece of fiction—too gentle in its tone but also too nuanced in dissecting its various themes of identity, segregation and race issues, transition, and the choices one oughts to make. Brit Bennet develops her characters using a score of subplots—Stella making a friend out of her black neighbors but eventually betraying them, the transition of Jude's boyfriend into a transgender man, and Kennedy finding it hard to trust her mother and grows into a restless woman who makes reckless choices.

The critics have called Bennet's The Vanishing Half her magnum opus that puts into perspective various subtle issues of race and belonging, but, in reality, the novel talks about the choices or their lack thereof that catapult us into unforeseeable circumstances where our mere survival depends on in Masha Gessen's words "inventing our lives continuously" as Stella does: she befriends a black family in her segregated neighborhood, betrays the family eventually, starts school again, grows weary of her husband, becomes a math professor while fighting her daughter off through all of this so she may not know that her mother was not, actually, white.

Russian-American journalist Masha Gessen wrote these words in an essay they published in 2018. Their essay mainly covered the choices they had made throughout their lives starting from when their parents decided to move to the States, which was followed by their doctor telling them that they had to choose by removing their breasts or ovaries (they eventually had to remove both and then uterus too). This was followed by their eventual decision to take hormones and their decision to regrow their breasts, and the choice they made when they decided to move back to Russia and the choice they did not make when they had to leave Russia in the aftermath of 2011-12 Pussy Riots lest secret services officials come for her kids.

In the same vein, Brit Bennet's novel The Vanishing Half talks about choices. It talks about an awful lot of things but the choice that one of the protagonists makes—to cash in her light skin for a life where the white people would think of her as one of their own—sets the entire plot of the novel. The novel is a piece of historical fiction, released last year, set in four different time settings from 1968 to 1988, and it follows the lives of two twins born in the southern state of Louisiana in a town that one of the twin's boyfriend tried to locate on a map in vain and which is named Mallard.

The novel follows two twins named Desiree and Stella as they navigate their life when one day they run away to New Orleans leaving their light skin-obsessed hometown and their mother behind. Initially, they get along well and take on jobs to make ends meet until Stella who is much of a 'tragic mulatto' (an archetypical mixed-race person who is perpetually sad for they do not fully belong to either of the 'black' or 'white worlds') eventually decides to leave Desiree for good and start a new life with her boss leaving her a small handwritten note that says sorry. Her light skin stays loyal to her and she passes onto the white world with ease. It is unclear whether Stella derives a sense of belonging or a sense of security in the white world.

Perhaps, it is just some sort of identity incongruence that she seeks to eliminate or it is that the twins are witness to their father's tragic murder who Desiree recalls had a skin "so light that, on a cold morning, she could turn over his arm to see the blue of his veins. But none of that mattered when the white men came for him." that drives Stella to blend into a white LA so that she can stop having nightmares wherein she is being dragged out and beaten to a pulp by white men.

Stella leaving her sister for a white world sets the course of the novel and also their new generation's—Desiree's blackened and bookish daughter named Jude and Stella's hedonist and a hippie of a daughter named Kennedy—relentless quest to understand the person that was one girl's Aunt and the another's mother. Stella always found it hard to hide the lie that was her phenotype. To her daughter, she always seemed like someone she barely knew, someone who hardly ever answered her (Kennedy's) personal inquiries into her life, and someone who could hardly keep up with the facade they had chosen to embody (that they were white).

On the other hand, her seven minutes elder twin Desiree moves through her life as unsentimentally as she could. After Stella elopes, she barely knows how to do life without her. Thus, she trails back to the life in her little town with her young daughter—broken from a marriage with a man who did not love her enough to not beat her. Desiree, unlike her lost twin, makes choices that seek to amend the wrongs of her previous choices. She does not marry again even though she meets her long-lost lover who looks after her mother and brings her presents everytime he comes back from his "criminal-hunting" job.

Eventually, Jude finds her Aunt when she leaves for her studies. She even tells her cousin everything that her mother would not. There is also a homecoming when Stella goes back to see her home to see that her mother is too worn out by Alzheimer's to recollect that her daughter had returned two and a half decades later. She leaves after staying just one day without bidding farewell while the purpose of her coming is to tell Desiree to stop Jude from revealing who she was or where she belonged to Kennedy.

Brit Bennet has produced a marvelous piece of fiction—too gentle in its tone but also too nuanced in dissecting its various themes of identity, segregation and race issues, transition, and the choices one oughts to make. Brit Bennet develops her characters using a score of subplots—Stella making a friend out of her black neighbors but eventually betraying them, the transition of Jude's boyfriend into a transgender man, and Kennedy finding it hard to trust her mother and grows into a restless woman who makes reckless choices.

The critics have called Bennet's The Vanishing Half her magnum opus that puts into perspective various subtle issues of race and belonging, but, in reality, the novel talks about the choices or their lack thereof that catapult us into unforeseeable circumstances where our mere survival depends on in Masha Gessen's words "inventing our lives continuously" as Stella does: she befriends a black family in her segregated neighborhood, betrays the family eventually, starts school again, grows weary of her husband, becomes a math professor while fighting her daughter off through all of this so she may not know that her mother was not, actually, white.