Land and property rights have long been contested by various parties post-independence. And if the latest judgment from the Balochistan High Court suggests anything, the contestation of land will remain a consistent phenomenon, even if the Pakistani state, and various private housing schemes expand into the peripheral parts of the country.

Balochistan has long been considered a rugged terrain, ripe with natural resources and hence, extremely suitable for mining and electricity projects. Yet, the statistics show that more than 90% land of Pakistan’s largest province is unsettled, owing both to the terrain and the lack of agricultural avenues.

Indigenous tribes, mostly semi-nomadic in nature, however, have kept on having partial settlements throughout this land, during both the colonial period and in independent Pakistan. In this context, these local tribes filed a petition in the Balochistan High Court to determine the status of this land, claiming their ownership. What followed is a court case, between the indigenous tribes and the government of Balochistan, eventually leading to a landmark constitutional interpretation, and a crucial reading of land ownership itself, a markedly progressive attempt which seems to uphold the constitutional and legal rights of a group often marginalised by the post-colonial state.

The colonial government had sought control over the revenue records and the administration of these lands, despite fringe resistance from indigenous tribal lords and agriculturalists. And similar to the bureaucratic machinery and the army, the Pakistani state dealt with this issue through an extension of the colonial project. The state got control over the revenue records and maintained its position as an authoritative body. Rather than create avenues for re-settlements or establishing documentation of the tribal presence, the state merely sought to administer the vast area both through a de-facto presence, and through some mining and agricultural projects. Legally, the government of Balochistan, as determined by the High Court, had no formal ownership over the area.

It is within this context, that the court’s judgment breaks away from established patterns of ownership designation. In the 22 page judgment, the court rules that it is the indigenous tribes of Balochistan, who have long inhabited the area, that possess both the right to claim for these lands, as well as pointing towards the government’s responsibility in documenting and resolving settlement disputes in these lands. And perhaps most crucially, responding to the government’s claim that there exists no formal proof of ownership, the court points towards firstly the colonial courts that selectively allowed informal documents to be presented in the court, and secondly of the evidence of ‘collective possession’ that has existed amongst the forefathers of different tribes. This is a distinctively progressive interpretation of the Articles 23 and 24 of the Constitution, that allow the right to private property both of movable possessions and immovable ones like land.

By pointing towards the legal significance of informal documentation, and hence by extension, the claims of indigenous tribes and their material possessions, the court shifts contemporary discourse in a number of ways. It goes directly against trends in Punjab, where the courts have been absent or legally insignificant in protecting villages from forcefully being taken by private housing schemes. The Balochistan High Court’s decision acts as an imperative first step in acknowledging the lands of Balochistan not as uninhabited like the colonial government imagined, but rather containing within it semi-nomadic tribes that must also be given legal status as awarded to the citizens of Punjab or Sindh.

Furthermore, the instructions to the government in ensuring re-settlements is another important step that would extend documentation, and further the legal protections for a historically marginalised group.

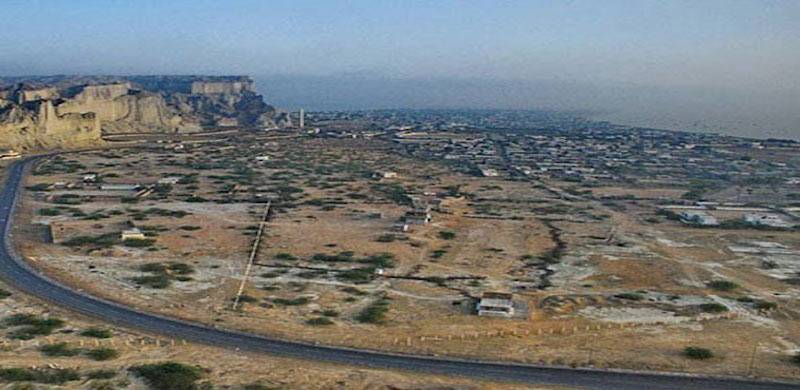

It is only through documentation of land and hence the produce of the land, that the indigenous tribes can formally participate in the economy of Pakistan. Perhaps most important however, is the political moment in which this Judgment arrived. In 2020, reports over Gwadar’s fencing caused significant backlash, as Balochs were denied access to their own land, despite Gwadar’s economic development as a potential economic and tourist hub. Within this complex situation, the Judgment displaces the authority of the state in creating fenced regions, and allows for an avenue that benefits the people of Balochistan.

If Pakistan is to include the Baloch in the economic revamping of the province, denying them their land is likely to transpire into further polarization. Therefore, the judgment is the first in many steps that the state must take to fully integrate Balochistan into its own vision of economic and social progress.