On the 30th of September 1938, the British Prime Minister returned from the Munich Conference. As soon as he landed in the UK, he gave a passionate speech to the crowd that had assembled outside the airfield. The document that fluttered in his hands and from which he read to the enamoured crowd contained a so-called agreement between himself and the German Chancellor to refrain from starting a war. This, according to Chamberlain, was “peace for our time.” Less than a year later, the Second World War was underway between the Axis and the Allied powers. Perhaps, I shall now say that the rest is history.

But then, why let the British PM go scot-free for ushering the world into a war? The Munich agreement was the latest in his series of overtures to the Führer. Even though the policy of appeasement didn't start with Chamberlain in office, he was one of its most puritanical pursuers in the British government. The violations of the Treaty of Versailles date back to 1935 when Germany was allowed to keep a standing military, and later it was later given permission to build up its navy. The Allies sat back and watched while Hitler consolidated his grip on power. Nobody dared to oppose Nazi power when they made inroads for their sympathizers in the Austrian government. And then when they reoccupied the Rhineland, followed by the annexation of Austria (Anschluss), there were fe repercussions for them. Still to come was the German memorandum to the Czechoslovakian government where the latter were threatened with military aggression if they tried to stall the German occupation of Sudetenland (Czech territory where people who were ethnically Germans lived). Britain and the French were bound by treaty to protect Czechoslovakian sovereignty in the face of foreign aggression, yet both the countries unceremoniously granted the Führer's wish when they signed the Munich agreement whereby Sudetenland was relegated to the Germans. The power-wielders in Paris and London thought that if they continued appeasing Hitler, he would one day be truly appeased. The Conservative party in Britain itself had a small faction of doomsayers in Churchill, Cartland and Macmillan who had, in vain, kept warning about what was to come. Churchill famously called the Munich Agreement "a total and unmitigated defeat" in his speech to the House of Commons but he was heckled down by the majority which believed that Hitler was finally appeased.

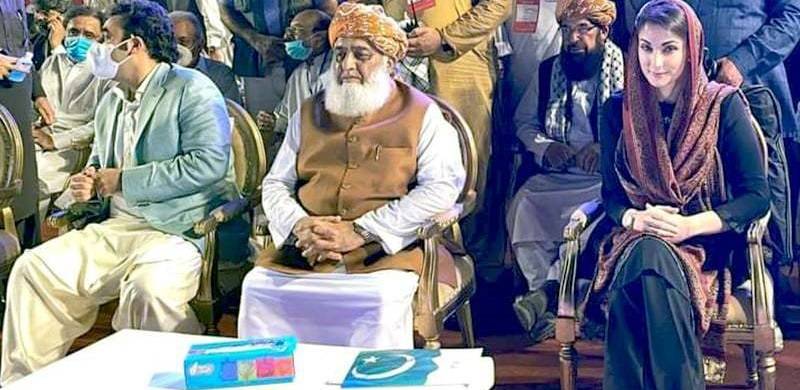

There are lessons to be learned from all of this when we in Pakistan today examine the Pakistan Democratic Movement's (PDM) defeat in the Senate polls. The point is that history offers good lessons to those who take them. Certainly, those who keep pursuing the facade of 'appeasement' or 'neutrality' must at some point in time confront the unpromising reality that they cannot 'appease' or 'neutralize' their tormentors without an all-out war. Democracy is only the 'best revenge' when – after your relentless kowtowing – the junta decides to play neutral for just one day and then you win for that day. And your mantra is still lingering in the air when the junta undercuts you the next day.

According to the latest revelations, the PDM knew about the members who were compromised and so to make sure they don't betray the junta or their party, they were instructed to affix the stamps on the PDM candidate's name in a way that the illegality of their vote can be later contested. (Report by Geo TV). Similarly, in Punjab the PML-N brokered an agreement between itself and the PTI and apportioned the senate seats between each other. Whatever happened to their rhetoric of overthrowing PTI? In the aftermath of the Senate vote on the bill of extension of Army Chief's tenure where PML-N had voted in favour of the bill, Babar Sattar wrote a damning refutation of that party's strategy in his column for The News which was titled "What Does the N Stand for?" In his column, Sattar laid bare how the entire narrative of "vote ko izzat do" rang hollow when juxtaposed with PML-N's decision to vote for the COAS extension.

One year hence when the opposition has come together under the mantle of PDM, we still don't know what it really wants to achieve. It seems like it is about time that they set out on a different course. Or else the public will start seeing through their good-for-nothing narratives. If they can bring themselves to digest the sad reality that the Umpire will never be neutral, then perhaps that would do them more good than Gillani's win would have done.

When Hitler invaded Poland, Neville Chamberlain was still acting like a businessman – trying to bring a diplomatic solution to the war. But when Hitler invaded the neutral states of Norway and Denmark, then it dawned upon the House of Commons in London that their appeasement was not going to get them anywhere. What followed was a three-day historic debate in the UK's parliament, now known as the Norway Debate. During the course of these deliberations and a final vote of confidence, Chamberlain lost his job as the leader of the country and the minority that kept calling for an all-out war prevailed as the incumbent government. In a stunning rebuke of the policy of appeasement, the Liberal Party old-guard ripped the Chamberlain government to shreds in his speech when he said, "You have sat too long here for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go."

The PDM seems to have some strange amnesia as they have been deceived several times in the holy name of neutrality. It's high time that they learn their lesson lest they want the junta to keep playing carrot and stick with them.

And if the PDM keeps sailing in two boats, its slogans will soon start loosing their lustre, the crowds will shrink and the electorate will get disenchanted.

But then, why let the British PM go scot-free for ushering the world into a war? The Munich agreement was the latest in his series of overtures to the Führer. Even though the policy of appeasement didn't start with Chamberlain in office, he was one of its most puritanical pursuers in the British government. The violations of the Treaty of Versailles date back to 1935 when Germany was allowed to keep a standing military, and later it was later given permission to build up its navy. The Allies sat back and watched while Hitler consolidated his grip on power. Nobody dared to oppose Nazi power when they made inroads for their sympathizers in the Austrian government. And then when they reoccupied the Rhineland, followed by the annexation of Austria (Anschluss), there were fe repercussions for them. Still to come was the German memorandum to the Czechoslovakian government where the latter were threatened with military aggression if they tried to stall the German occupation of Sudetenland (Czech territory where people who were ethnically Germans lived). Britain and the French were bound by treaty to protect Czechoslovakian sovereignty in the face of foreign aggression, yet both the countries unceremoniously granted the Führer's wish when they signed the Munich agreement whereby Sudetenland was relegated to the Germans. The power-wielders in Paris and London thought that if they continued appeasing Hitler, he would one day be truly appeased. The Conservative party in Britain itself had a small faction of doomsayers in Churchill, Cartland and Macmillan who had, in vain, kept warning about what was to come. Churchill famously called the Munich Agreement "a total and unmitigated defeat" in his speech to the House of Commons but he was heckled down by the majority which believed that Hitler was finally appeased.

There are lessons to be learned from all of this when we in Pakistan today examine the Pakistan Democratic Movement's (PDM) defeat in the Senate polls. The point is that history offers good lessons to those who take them. Certainly, those who keep pursuing the facade of 'appeasement' or 'neutrality' must at some point in time confront the unpromising reality that they cannot 'appease' or 'neutralize' their tormentors without an all-out war. Democracy is only the 'best revenge' when – after your relentless kowtowing – the junta decides to play neutral for just one day and then you win for that day. And your mantra is still lingering in the air when the junta undercuts you the next day.

According to the latest revelations, the PDM knew about the members who were compromised and so to make sure they don't betray the junta or their party, they were instructed to affix the stamps on the PDM candidate's name in a way that the illegality of their vote can be later contested. (Report by Geo TV). Similarly, in Punjab the PML-N brokered an agreement between itself and the PTI and apportioned the senate seats between each other. Whatever happened to their rhetoric of overthrowing PTI? In the aftermath of the Senate vote on the bill of extension of Army Chief's tenure where PML-N had voted in favour of the bill, Babar Sattar wrote a damning refutation of that party's strategy in his column for The News which was titled "What Does the N Stand for?" In his column, Sattar laid bare how the entire narrative of "vote ko izzat do" rang hollow when juxtaposed with PML-N's decision to vote for the COAS extension.

One year hence when the opposition has come together under the mantle of PDM, we still don't know what it really wants to achieve. It seems like it is about time that they set out on a different course. Or else the public will start seeing through their good-for-nothing narratives. If they can bring themselves to digest the sad reality that the Umpire will never be neutral, then perhaps that would do them more good than Gillani's win would have done.

When Hitler invaded Poland, Neville Chamberlain was still acting like a businessman – trying to bring a diplomatic solution to the war. But when Hitler invaded the neutral states of Norway and Denmark, then it dawned upon the House of Commons in London that their appeasement was not going to get them anywhere. What followed was a three-day historic debate in the UK's parliament, now known as the Norway Debate. During the course of these deliberations and a final vote of confidence, Chamberlain lost his job as the leader of the country and the minority that kept calling for an all-out war prevailed as the incumbent government. In a stunning rebuke of the policy of appeasement, the Liberal Party old-guard ripped the Chamberlain government to shreds in his speech when he said, "You have sat too long here for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go."

The PDM seems to have some strange amnesia as they have been deceived several times in the holy name of neutrality. It's high time that they learn their lesson lest they want the junta to keep playing carrot and stick with them.

And if the PDM keeps sailing in two boats, its slogans will soon start loosing their lustre, the crowds will shrink and the electorate will get disenchanted.